Voices from the Other Side: Aomori’s Traditional “Itako” Mediums

Society Culture Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Faith in Japan

Many in Japan are under the impression that the Japanese are “not religious.” But look at daily life here, and one could say that they are among the most religious people in the world.

The return to the family home during the summer Obon season is one good example. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this custom has fallen away somewhat, but previously people would make the annual journey to pay respects to ancestral graves, even though the expressways were packed.

The practice of saying itadakimasu before eating is an expression of gratitude to the myriad kami (deities), and contrition to the living things providing that food. And each year, insecticide manufacturers hold memorial services for the cockroaches and flies their products have exterminated. Is there any other nation quite like this one?

If faith means acting according to religious convictions, the above customs undoubtedly fit this description. It may be true that it is uncommon to strongly identify as a believer in a religion with a specific founder, like Buddhism, Christianity, or Islam. Yet, many Japanese people have a firm faith.

What, then, is the faith that forms a base for the Japanese? Ukai Hidenori, a religious journalist and Jōdo Buddhist priest at the Kyoto temple Shōgakuji, offers the following analysis.

“As well as being a mixture of animism, Buddhism, Shintō, Confucianism, and other beliefs, the faith of the Japanese includes regional characteristics, so it is difficult to summarize briefly. If I were to simplify, however, at heart it is based on nature worship and ancestor memorial.”

This faith is the soil that brought forth the female mediums known as itako.

Spirit and Flesh

Aomori Prefecture’s itako perform many roles, but they are likely best known for kuchiyose, in which they summon and become possessed by the spirits of the dead in order to convey their words to the living.

The religious scholar Yamaori Tetsuo says that a belief in the dualism of spirit and flesh, whereby spirits live on after the demise of the body, is fundamental to Japanese views of life and death. This is behind the act of chanting by itako to call forth ancestors from beyond the grave, and has a great influence on Japanese people’s lives.

In the Obon custom of adding stick legs to cucumbers to make them into “horses” and to eggplants to create “oxen,” these spirit animals are intended to carry ancestors between this world and the next one. The Gozan Okuribi, in which bonfires are lit on five mountains in Kyoto on August 16, is also a ritual meant to guide spirits from the various earthly homes they have visited back to the mountains.

It is widely believed in Japan that after the spirits of the dead leave their bodies, they are purified through offerings from their descendants, becoming kami in their final memorial service held either 32 years or 49 years after their death. Before this, the spirits are thought to live in the mountains and return home at Obon, the New Year Shōgatsu season, and the Higan periods around the spring and autumn equinoxes. In coastal regions, they may also be thought to live in the sea.

It is likely that the ancient reverence for mountains among the Japanese led to the belief that the spirits of the dead reside there. The channeling of spirits by itako is an expression of this faith that lies deep in the nation’s psyche.

Apprenticeship with a Mentor

Although today most closely associated with kuchiyose, originally itako acted as a kind of spiritual local counselor, offering up advice to the women in the area on relationships between mothers- and daughters-in-law and husbands and wives, as well as health matters.

In ancient Japan, miko conveyed the words of kami and the dead. Today, female shamans like the yuta in Okinawa and Amami and the Ainu tuskur perform a similar role, along with the kamisama and gomiso in many parts of Tsugaru in western Aomori Prefecture.

The itako are different from these shamans in that they acquire their techniques through spiritual training. While the yuta and kamisama are often suddenly possessed one day by a kami, the itako undergo an apprenticeship with an experienced mentor lasting several years.

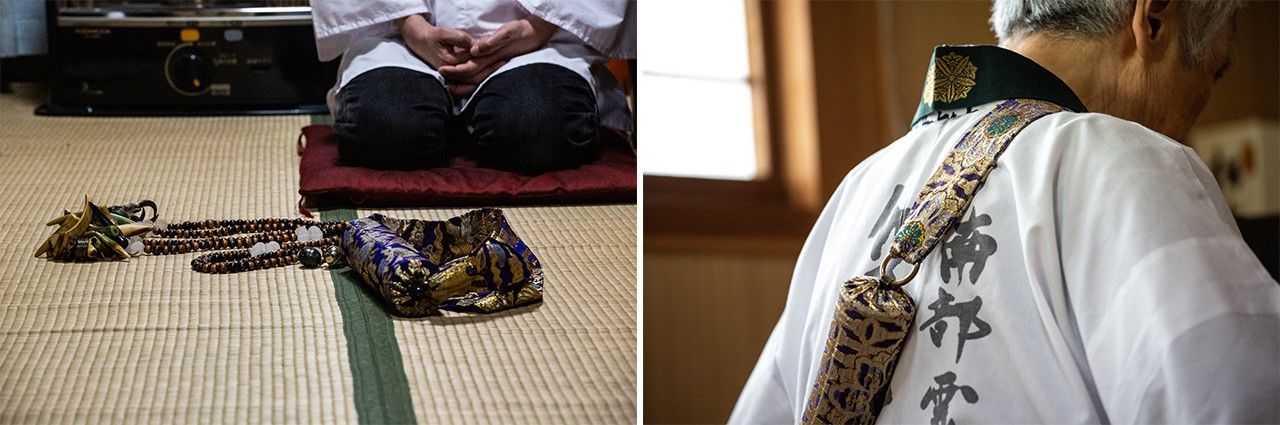

This means that traditional itako have a certificate of mastery known as an odaiji, as well as prayer beads received from their mentor.

Irataka prayer beads (left) are strung together with wild boar fangs and pieces of deer horn to ward off evil, and old coins to pay the ferry fare across the Sanzu River into the afterlife. The odaiji is a bamboo tube holding part of a sutra, and is worn on the back to keep evil spirits away. (© Aya Watada)

Supporting the Vulnerable

This mentor-disciple relationship derives from the history of itako becoming established as a vocation for blind women.

Esashika Hitoshi is a local historian in Hachinohe, Aomori Prefecture, and head of the Aomori Prefectural Association for Preserving Itako Traditions. He says that around 250 years ago, there was a blind shaman woman called Taisobā in the Nanbu region, which is now eastern Aomori. She passed on her techniques like channeling the dead to Chōrinbō, a yamabushi or ascetic priest, and his wife Takadatebā, who was herself blind, and they later taught and organized blind women into the group that became the itako.

As their disciples gained disciples of their own, itako culture spread. The words chanted for kuchiyose vary depending on the different mentors. While Takadatebā’s own blindness was likely a motivating factor in teaching women who could not see, this education is also thought to have been a way of assisting those in otherwise precarious circumstances.

Historically, Tōhoku had poor food and sanitary conditions, and some children lost their eyesight as a result of measles. How to support them in the community was a major issue. While blind men tended to specialize in acupuncture, moxibustion, massage, and playing the shamisen, women became itako and were involved in Shintō rituals.

As local needs for a medium between the living and dead brought girls into the profession, itako became fixtures in the Nanbu and Tsugaru regions. It is thought that there were still dozens of itako in Nanbu from around the 1950s to the 1970s.

Many in Japan associate the itako with the Osorezan area in Aomori, which has an active volcano and a caldera lake, and is considered one of Japan’s holiest sites, but there is no direct connection. Itako generally relocate from the regions where they are based to Osorezan in summer and autumn, when there are major festivals, for the purpose of finding customers.

The forbidding landscape of Osorezan. (© Aya Watada)

When itako get together, as at Osorezan, this is known as an itakomachi. Other traditional locations in Aomori included Buddhist temples such as Kawakura Sainokawara Jizōson in Goshogawara, Terashita Kannon in Hashikami, and Hōunji in Oirase. Kamisama and other shamans also participated in these gatherings.

Kawakura Sainokawara Jizōson has more than 2,000 statues of Jizō. (© Aya Watada)

The Last Itako

Recently, however, the itako face an existential threat. Esashi’s association recognizes only a handful of practitioners following historical traditions, and only one blind itako, who is the 90-year-old Nakamura Take. While Matsuda Hiroko, who has been called the “last itako,” is still young, in her fifties, she does not take disciples. There have not been any itako acting as mentors for a long time.

Nakamura Take (left) and Matsuda Hiroko. Matsuda is performing the now rare oshirasama asobase, a January ceremony for the household deity Oshirasama. (© Aya Watada)

Local populations are aging rapidly outside of Japan’s big cities, and this is particularly true for remote mountainous areas. In the last decade, many itako have retired or passed to the other side.

While the association is making efforts to preserve traditions, improved medical care means that fewer children lose their eyesight from measles, and there are many more job options, so it becomes more difficult to find potential future itako.

There may be an increase in self-described itako in the future, but the traditional kind, rooted in local communities, could well die out.

Sharing Fears and Grief

In August 2022, Kawazu Project, which I am the president of, published a photobook together with photographer Watada Aya called Talking to the Dead, which takes the itako as its subject. As well as the journalistic focus on recording the itako and their vanishing culture, I wanted to gain a new understanding of Japanese views of spirits and religion, which is the basis for practices like kuchiyose, and to convey this to readers in Japan and around the world. The book is bilingual, with writing in both Japanese and English.

My final feeling after completing the book is that itako are essentially there for sharing grief and providing consolation. They seem to be a kind of “grief care” system established by the people of the past.

The grief of losing a loved one or someone close is indescribable. The more unexpected that the death is, the greater the void it creates in someone’s heart. Many come to accept their grief over time, and process it in their own way, taking a new step forward with pain etched in their hearts. I feel that the itako provide the strength for that forward step.

While putting the book together, I put all of Nakamura Take’s words during kuchiyose into text form. Every one of them provided comfort to the person who wanted to hear from a loved one who had passed away, saying that all was well in the next world, and giving thanks for being called. They helped someone grieving to look toward the future.

Scientific advances have made our lives extraordinarily comfortable, but this has not meant a decrease in those who seek spirituality—I actually think such people are increasing. Material prosperity is not the same as emotional fulfilment. This, I think, is why people have tried to share their fears and grief with others through faith and thereby overcome them.

(Originally published in Japanese on December 27, 2022. Banner photo: Nakamura Take, a 90-year-old itako who lost her eyesight at the age of 3 after contracting measles. © Aya Watada.)