“Ningyo”: Japanese Merfolk and Auspicious Mummies

Culture History Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Historical Records

There are records of sightings of ningyo (merfolk) across Japan, mainly along the Sea of Japan coast from what is now Aomori Prefecture to Ōita Prefecture, from ancient times until around the middle of the Edo period (1603–1868). The earliest comes in the eighth-century Nihon shoki (Chronicle of Japan), describing events purported to have taken place in the twenty-seventh year of the reign of Empress Suiko (roughly 619), but it does not use the word ningyo. A creature “resembling a human” is seen in a river in Ōmi Province (now Shiga Prefecture) and a fisherman catches something that is “neither human nor fish” in Settsu Province (now parts of Hyōgo and Osaka Prefectures). In the Meiji era (1868–1912), the polymath Minakata Kumagusu suggested that these were observations of salamanders.

The word ningyo (人魚) first appears in Japan’s oldest Japanese-Chinese dictionary, Wamyō ruijūshō, in 937. Based on information from the Chinese geography text Shan hai jing (Classic of Mountains and Seas) and other sources, it is defined as having the body of a fish and a human face, with a childlike voice.

The 1254 collection of tales Kokon chomonjū (Record of Things Heard, Past and Present) describes the merfolk’s appearance in great detail. A story of Ise Province (now Mie Prefecture) in the previous century tells how fishermen catch three great fish. Their heads look human, but they have protruding mouths with small teeth, and faces like monkeys; when approached they cry out and burst into tears. The villagers eat one of the creatures, which is said to be “delicious.” The writer comments that, “perhaps these were ningyo.”

Detail from a ningyo offering talisman found at the Suzaki archaeological site in Akita Prefecture. (Courtesy Akita Prefectural Board of Education; © Jiji)

Azuma kagami (Mirror of Eastern Japan), a historical record assembled by the Kamakura shogunate, notes the appearance in 1247 of “a large fish like a human corpse” in the sea off Tsugaru (now Aomori Prefecture). This was the year of the Hōji Conflict in which the Hōjō clan, which held de facto power in the shogunate, destroyed its rivals, the Miura clan. The later Hōjō godai ki (Chronicle of the Hōjō Family Through Five Generations) saw this fish as a ningyo, and pointed to more than 10 other records of sightings, linking them with the turmoil of the time.

In 1999, a wooden tablet depicting a priest and what seems to be a ningyo was unearthed at the Suzaki archaeological site in Akita Prefecture. The tablet, which appears to be from around the second half of the thirteenth century, has writing that can be interpreted as saying, “Poor thing, but you must kill it.” In the medieval period, an age of regular conflicts, the appearance of a ningyo was taken as a bad omen, and the priest is thought to be depicted making an offering to ward off disaster.

As Seen by Natural Historians, Writers, and Artists

From the Edo period, works started to treat the ningyo from the perspective of natural history, which was developing through a fusion between honzōgaku (research into Chinese medicinal herbs) and rangaku (Western learning, which entered Japan via Dutch-language materials).

The ningyo of Wakan sansai zue (Japanese-Chinese Illustrated Assemblage of the Three Components of the Universe) matches the present concept of a mermaid. (Courtesy National Diet Library Digital Collection)

Kaibara Ekken’s 1709 work Yamato honzō (Japanese Medicinal Herbs) made reference to the sixteenth-century Chinese work Bencao gangmu (Compendium of Materia Medica) in recording the medicinal properties of ningyo bones, such as the prevention of bloody bowel discharges. Japan’s first illustrated encyclopedia, Wakan sansai zue (Japanese-Chinese Illustrated Assemblage of the Three Components of the Universe), also appeared in 1713, listing the ningyo alongside other types of fish, and explaining that its bones were used in the Netherlands as an antidote. The illustration of a woman’s upper half and a fish’s lower body is similar to today’s standard image of a mermaid.

In the 1786 work Rokumotsu shinshi (New Treatise on Six Things), Ōtsuki Gentaku quoted from Japanese and Chinese sources, as well as works by the famous French surgeon Ambroise Paré and the Polish naturalist John Jonston, concluding that merfolk existed and describing their appearance and medicinal effects.

Illustrations of merfolk in Rokumotsu shinshi (New Applications for Six Things) taken from works by John Jonston (left) and Ambroise Paré. (Courtesy National Diet Library Digital Collection)

The kokugaku (national learning) scholar Hirata Atsutane appears to have believed that ningyo both existed and provided medical benefits. In an 1842 letter, he talks of how he obtained a “ningyo bone” and chose a propitious day with friends to grind it up, add it to water, and drink it with the aim of achieving longevity.

Meanwhile, writers and artists created their own alluring mermaids. In Ihara Saikaku’s 1687 work Budō denraiki (Traditions of the Way of Samurai), he describes the appearance of a ningyo in 1247 in the sea off Tsugaru. Unlike the fish resembling a human corpse that is sighted in the same year in Mirror of Eastern Japan, Saikaku’s ningyo has the face of a beautiful woman with a chicken’s comb on its head. It gives off a sweet scent, and cries like a skylark. At the time, there were not many records describing ningyo in detail, so Saikaku may have incorporated his own imaginative flourishes.

In the nineteenth century, ukiyo-e artists Utagawa Hiroshige II and Kunisada collaborated on Kannon reigenki (The Miracles of Kannon), which features a floating woman with the lower body of a fish. The scene is of a mermaid who was human in a former life. She begs Prince Shōtoku—who has come to Ōmi Province to spread Buddhism—for salvation, and achieves enlightenment. Around the shores of Lake Biwa, the tradition remains that a ningyo appeared in the province, as described in Chronicle of Japan.

A mermaid appears to Prince Shōtoku in this scene from Kannon reigenki (The Miracles of Kannon). (Courtesy National Diet Library Digital Collection)

Youthful for 800 Years

Japan’s most famous ningyo tradition is the story of Yao Bikuni (meaning the “eight-hundred [year] nun”). There are many variations, centered on Wakasa Province (now Fukui Prefecture). The basic outline is of a father who acquires some ningyo meat, which his daughter eats. She remains youthful for 800 years and becomes a Buddhist nun, although in some stories she lives for 1,000 years, as in the variation handed down in Okayama Prefecture.

“There are no records of ningyo sightings in Okayama, but there are several traditions concerning Bikuni in the prefecture.” says Kinoshita Hiroshi, who heads the Okayama Folklore Society. “For example, there’s the story that when she was setting out to travel from province to province, she said, ‘I’ll return while this stick remains rooted,’ and she took the walking stick she was carrying and thrust it into the ground before leaving. It’s said that it took root and grew into a great tree.” There is also a story that a young person later traveled from Okayama to Wakasa and met Bikuni. The nun remembered her hometown and felt nostalgic for events almost a millennium ago.

“The meaning and role assigned to ningyo changed through different times and situations,” Kinoshita says. “They were often seen as ill-omened during the medieval period, but they might also be viewed as auspicious. During the Edo period, diseases like smallpox and measles were widespread, and the jinja hime [shrine princess] took on the prophetic, warning role that would later be associated with Amabiko and Amabie.”

This “shrine princess” was a servant from the undersea Dragon Palace said to have appeared in 1819 off the coast of Hizen Province (now parts of Saga and Nagasaki Prefectures). It predicted seven years of good harvests, but also spoke of a disease called korori (associated with cholera), advising that drawing and looking at its picture would provide protection against infection. The jinja hime had the face of a woman on the body of a dragon, with two horns on its head and three prongs on its tail. It became classified as a kind of ningyo.

The jinja hime (shrine princess). (Courtesy Miyoshi Mononoke Museum)

Beyond Japan’s Borders

Mummified ningyo went on display in Edo-period shows of curiosities, their popularity fueled by claims that viewing them and their pictures protected against disease and ensured long life. Some were ultimately presented to shrines and temples.

Kinoshita says that these mummies were probably made from the Edo period to the early Meiji era (1868–1912). “They appeared in shows, and some went over to Europe. There was huge demand for them. There must have been some highly skilled artisans creating the mummies.”

One specimen now in the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden, the Netherlands, was transported back by a Dutchman at the trading post in Dejima, Nagasaki, in the early nineteenth century. US impresario P. T. Barnum’s mummified “Fiji mermaid,” which became a big hit in 1842, was also likely to have been made in Japan. Many such mummies were produced by deftly attaching the upper halves of monkeys to the lower halves of salmon or other fish. In Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, US Commodore Matthew Perry mentions the creation of a mermaid by a Japanese fisherman, offering it as one example representing the country under the heading of “scientific knowledge and its applications.”

Today, ningyo mummies remain at temples and shrines across Japan, where they continue to be attributed with various powers, such as aiding longevity, good health, and safe deliveries, and warding off ill fortune. Sometimes, they are not on view to the public, however, and it is unclear how many there are nationwide.

There is a famous one at Kamuro Karukayadō, a Buddhist temple at the foot of Mount Kōya in Hashimoto, Wakayama Prefecture, that is recognized as a folk cultural property by the prefecture. It is about 60 centimeters in length, with an expression and pose that recall Edvard Munch’s The Scream, and is associated with the ningyo mentioned in Chronicle of Japan. The temple of Ganjōji in Higashiōmi, Shiga Prefecture, has a similar “Munch-style” ningyo mummy connected to the same source.

Other mummies with similar poses are kept at Myōchiji in Kashiwazaki, Niigata Prefecture, and Tenshōkyōsha in Fujinomiya, Shizuoka Prefecture—at 170 centimeters, the latter is a large specimen. Meanwhile, Zuiryūji in Osaka has a mummy with long hair and outstretched arms, and Kotohiragū in Kagawa Prefecture one that lies on its belly with its head raised.

Analysis of a Mummy

Kurashiki University of Science and the Arts in Okayama Prefecture is currently analyzing a ningyo mummy from the Enjuin temple in Asakuchi in the same prefecture. Kinoshita says his interest was drawn by finding a negative of the mummy taken by Okayama naturalist Satō Kiyoaki (1905–98) among his materials—Satō published Japan’s first dictionary of yōkai (spirits and monsters) in 1935. The university assembled a research team after Kinoshita made a request for a survey via Kurashiki Museum of Natural History.

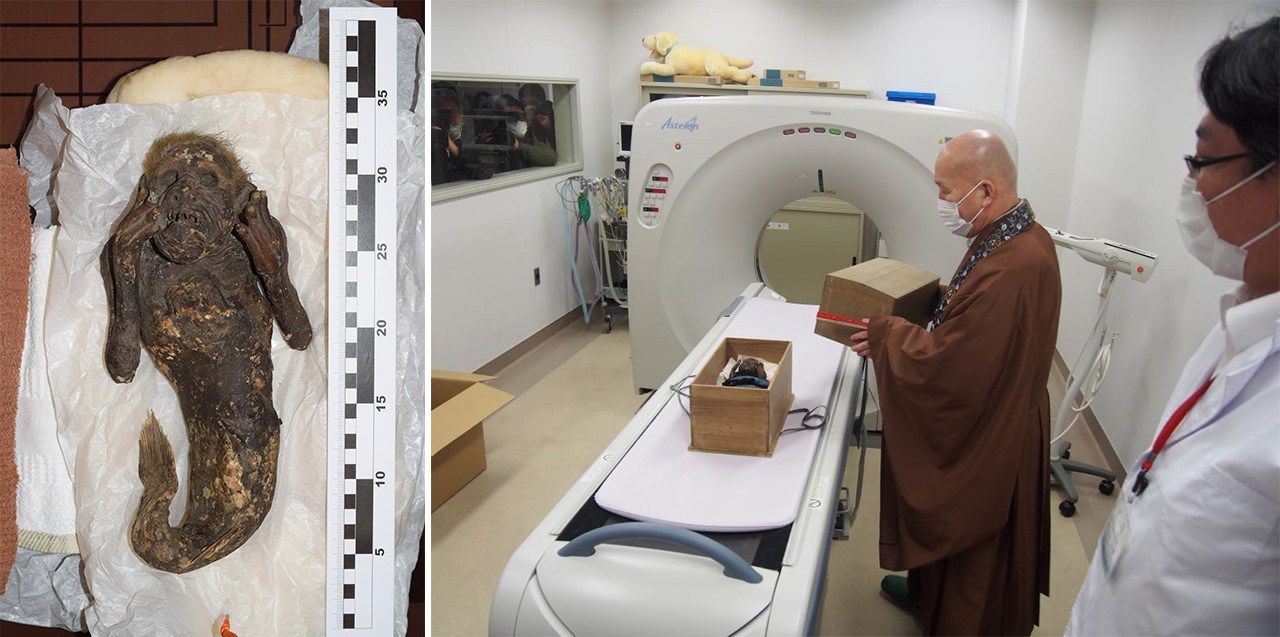

“I saw the mummy after making a request to Enjuin, and it’s in the ‘Munch style,’ around 30 centimeters in length. My first impression was that it’s small compared to the other mummies I’ve seen,” Kinoshita commented.

The note explaining the history of the mummy. (Courtesy Kurashiki University of Science and the Arts)

The box containing the mummy has a note that reads “dried ningyo.” Kinoshita says, “The note explains that it was caught in the sea off Tosa [now Kōchi Prefecture] during the Genbun era [1736–41], and because it was unusual, it was dried and brought to Osaka. The Kojima family of Fukuyama, Hiroshima Prefecture, bought it and kept it as an heirloom. Then, it came to Enjuin, but we don’t know by what route.”

According to the interim report published in April, the hair, eyebrows, ears, arms, and hands with five fingers and flat nails are like those of primates. The teeth, however, suggest a meat-eating fish. There are also apparently some scales on the upper half that differ from those on the lower half. The final report, including a folklore survey, is scheduled for this autumn.

The Enjuin mummy (left) and Kuida Kōzen, the temple’s chief priest, observing a CT scan. The mummy will go on display at Kurashiki Museum of Natural History this summer. (Courtesy Kurashiki University of Science and the Arts)

Kinoshita comments, “The university will use DNA analysis to find what fish it resembles and carbon dating to identify the time period it comes from. Together with my historical and ethnographic approach, I’m looking forward to what new discoveries we make concerning ningyo.”

Since the Meiji era, there have been many suggestions for what people actually saw in purported ningyo sightings—from salamanders, dugongs, and manatees to sea lions, seals, and oarfish. Whatever the truth, the belief in ningyo as real creatures continued until the end of the Edo period, and they became the focus of faith, seen as providing blessings. The countless materials and the various mummies that have been carefully preserved until the present day demonstrate how ningyo were accepted into the hearts of Japanese people as something more than imaginary beings.

(Originally written in Japanese by Kimie Itakura of Nippon.com and published on April 26, 2022. Banner photo: Detail from a ningyo offering charm found at the Suzaki archaeological site in Akita Prefecture, at left [courtesy Akita Prefectural Board of Education; © Jiji], and the Enjuin ningyo mummy [courtesy Kurashiki University of Science and the Arts].)