Gacha-Gacha: A Half-Century of Mystery Goodies from Japan’s Capsule Toys

Culture Society Lifestyle Entertainment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Catching the Eye

The head offices of Kitan Club strike one as more toy shop than corporate outpost. Visitors are greeted at the main entrance by life-size figures of a shoebill and a gorilla, and toys great and small are to be found throughout the rooms.

This makes sense, given the company’s focus as a producer of trinkets found in Japan’s “capsule toy” machines. These devices, which dispense a plastic capsule containing a small prize in exchange for some coins and the twist of the knob, have a variety of names, all onomatopoeia for the sounds of their use: gacha, gacha-gacha, or gashapon.

Wooden shelves near Kitan Club’s entrance display the company’s capsule toy releases over its 15-year history, and the sheer variety of shapes and configurations arrests the eye. Among them you will find the company’s biggest hit product: the Koppu no Fuchiko (Cup Fuchiko) series. It features figurines of a woman named Fuchiko (a play on the Japanese word for a cup’s rim, fuchi) in all kinds of poses, made to balance on the rim of a cup or glass. The playful designs and incredible variety are just right to whet collectors’ appetites. The figurines quickly became a viral hit on social media after their 2012 launch, particularly with young women, but the popularity has grown across generations. With the Sports series, released in July 2021, sales have now surpassed 20 million figures.

Kitan Club also produces all kinds of cat figurines. Here are the somewhat grumpy Kamibukuro ni haitta neko (Cat in a Paper Bag) series (left) and the Neko jita take (Mushroom-Cat Tongues) magnets.

The first generation Koppu no Fuchiko (left) and Soccer Fuchiko from the Sports series. (© Tanaka Katsuki/Kitan Club)

“We developed Fuchiko with the manga artist Tanaka Katsuki,” says Kitan Club President Furuya Daiki. “We work with artists like Katsuki or sculptor Hashimoto Mio, but some of our ideas come out of our monthly planning meetings. We have around twenty employees now, and most attend the meetings, where everyone draws out their own ideas. If it’s not interesting at first glance, it’s out, but if everyone is instantly into it, it passes,” he explains.

“One of our strengths as a small company is that we can move something from the idea stage to a finished product quickly. It takes a lot of time for the big companies to get things through planning.”

Figurines from woodcarver and sculptor Hashimoto Mio’s Aquarium & Zoo series. (© Hashimoto Mio, from the Kitan Club website)

Rings Out of Rice Ball Filling

They release between four and eight new varieties each month. Their latest hit is Onigiringu (a pun combining onigiri, or rice ball; gu, or filling; and ringu, the Japanese pronunciation of ring), which came from an employee’s idea. The first single-item release came out in 2019, but it has since become a series, with the fourth release dropping in the summer of 2021. The toys feature a rice-ball shaped case containing a ring whose “gem” is shaped like traditional rice ball fillings―umeboshi pickled plum, salmon flakes, salmon roe. “Younger people are posting pictures on Instagram and showing them off to their friends, just like with Koppu no Fuchiko. Even after the Fuchiko collection craze, I didn’t think we’d have so many people buying up loads of Onigiringu.”

Popularity in the capsule toy game can be fickle. According to Furuya, “Cats, frogs, and mushrooms” are some basic elements of a hit, but it can be hard to predict what will really spark a craze. Social media buzz seems to be key.

The employee’s original idea sheet. The idea was eventually released as Ika to wata bōru chēn tsuki figyua (Squid and Innards Figure on Ball Chain) and Onigiringu.

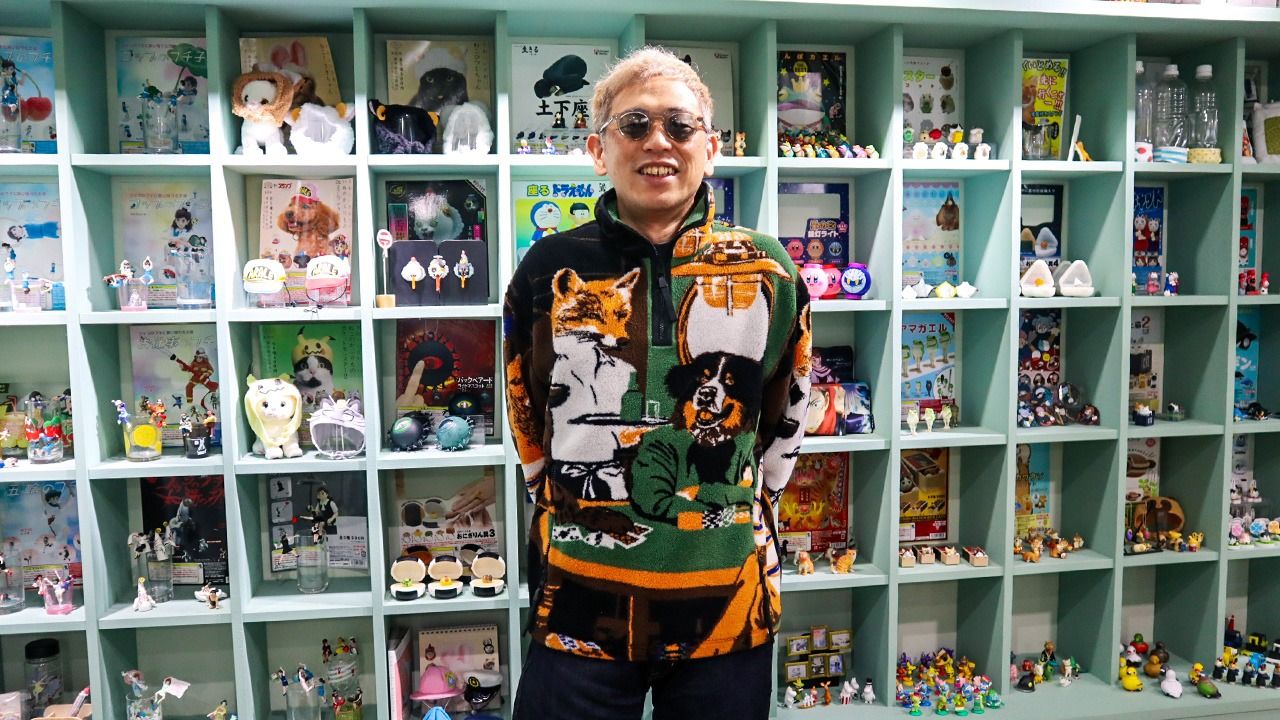

Left: President Furuya holding an Onigiringu figure. Right: Phone straps come in shapes ranging from seated salarymen to whimsical frogs.

Furuya left his job with capsule toy manufacturer Yūjin (now Takara Tomy Arts) and went solo in 2006, at the age of 30. He was part of the generation that grew up obsessed with Kinnikuman erasers—tiny rubber reproductions of characters from the popular pro-wrestling-themed fantasy anime—bought from gacha machines set up in front of candy shops. For his own company, though, he decided to focus on a new, more adult-oriented market.

“I knew that with Japan’s shrinking birthrate, there would be fewer and fewer children, so I narrowed my focus on adults from the start. The business started out in the red because we put quality above everything, but then Fuchiko blew up and the business took off. The last five years have seen new competition growing rapidly, though.”

Onoo Katsuhiko, head of the Japan Gachagacha Association, also worked at Yūjin before Furuya joined. Now, he works as a consultant and gacha event planner. According to Onoo, the capsule toy market is worth around ¥40 billion annually, and has grown by around 50% in the last ten years. Major players Bandai and Takara Tomy Arts hold about 60% of the market, but new companies have been making inroads in recent years, and there are now around 30 smaller firms primarily targeting adults. About 300 new products hit the market each month, sold out of some 600,000 vending machines nationwide. The items mostly sell in the ¥300 to ¥500 range, and the reasonable prices help drive their popularity.

Into the Fourth Popularity Wave

Onoo, an expert on capsule toy history, says that the toys actually have their origin in the United States.

“The United States had gumball machines, and then they started putting toys in them. Around the Second World War, President L. O. Hardman of the US trading company Penny King came to Japan to buy celluloid toys to put in those vending machines. The first capsule toy machines appeared in Japan in 1965. That same year, Hardman helped set up Japan’s Penny Shōkai, which began setting up machines imported from the United States. Children were soon hooked on the machines in front of candy stores. They were so popular, the pictorial magazine Asahi Graph ran a special feature on them in 1966”.

Left: Japan-made celluloid toys imported to the United States in the early postwar period. Right: a Penny Shōkai sign. (From Onoo Katsuhiko’s collection)

“For children, it became their first experience of ‘gambling’ with their own allowance. They took 10 or 20 yen out of their wallet, and turned the handle. But there was never any guarantee that the toy you want, the ‘jackpot,’ would drop. It’s a serious game, a game of hope and disappointment. I’m fifty-six now, and I grew up spinning those knobs in front of the candy shop. Now, with the high quality of the goods, the gap between winning and losing has narrowed. But still, I love that doubt and frustration of not knowing what is going to come out.”

Children gathered in front of a candy shop. Most machines charged ¥10 at the time. (Originally published in Asahi Graph in 1966; from Onoo’s archives)

Bandai entered the capsule toy market in 1977. The company launched products based on its own characters at a price of ¥100, while most others charged around ¥20. Bandai’s Kinnikuman character erasers, launched in 1983, went on to sell 180 million pieces. The Gundam series also became a huge source of hits. Onoo calls this period the first wave of gacha popularity; Yūjin came on the scene during this era, in 1988.

The second wave came in 1995, sparked by the release of Windows 95 and the new trend of blogging. People started writing about the pleasures of gacha toy collecting on their blogs, and soon after, Bandai’s new full-color HG Ultraman series, sold for ¥200, became a big hit. Until then, all gacha toys were monochromatic. Disney character figures began to appear, and the market began spreading beyond children to their parents as well.

The third boom came in 2012, with Koppu no Fuchiko. The spread of smartphones helped drive that. “The iPhone came to Japan in 2008,” notes Onoo. “In 2012, the year Fuchiko came out, the number of smartphones finally surpassed the number of galakei feature phones in Japan. Products with detailed design made in cooperation with artists, like Fuchiko, are perfect for social media, especially among women consumers, and that helped their popularity grow.”

And now we are in the fourth wave. “It’s characterized by specialty shops targeting women specifically. From 2019, shops like Gacha Gacha no Mori have been spreading all over the country, and roughly 60 percent of their customers are women.”

Gacha as Artistic Self-Expression

Gacha toys that replicate objects found in daily life are an increasingly common object. There is a huge range of mundane goods, from home furniture to ice shavers that can actually shave ice, or water coolers that actually dispense water, and even, for some reason, toilet slippers.

Recently, items producing sound are popular. With bath remote controls that tell you that your bath is ready when you press a button, bus stop buttons, doorbells and “nurse call” buttons, these toys seem to satisfy a hidden desire to press buttons over and over again.

An amazing variety of miniatures from Onoo’s collection.

The rapid increase in adult-oriented products has also heralded a rise in young creators who specialize in planning and designing gacha toys. “With more manufacturers, the barriers to commercialization have dropped, and these young artists can get more exposure. Gacha offer a chance at self-expression. For example, Zarigani Works is a pair of creators who found a hit with their Dogeza suru sararīman, or Abject Apology Businessman, cellphone straps sold by Kitan Club, and have a new level of exposure. More recently, they released the Ishi [stone] series through Bushiroad Creative,” Onoo says.

According to Onoo, the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 caused a temporary drop in sales at capsule toy specialty shops, but they soon bounced back. In August of 2020, Bandai Namco opened its flagship Gashapon Department Store in Ikebukuro. It is filled with around 3,000 machines, and now is in the Guinness World Records as the largest single-shop collection of capsule toy machines. In October that year, the film version of Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba opened in theaters to enormous success, contributing to a massive increase in capsule toy sales.

Digital Gacha a New Market Mainstay

Furuya, president of Kitan Club, believes that the number of brick-and-mortar stores will begin falling in the near future, and online gacha targeting young “digital natives” will become a new market cornerstone. “The content will go digital, I think, like music, videos, or art. I think our company needs to take the lead in opening up a new digital gacha market.”

He links the idea to recent news of a “travel gacha.” Budget airline Peach Aviation set up a travel drawing vending machine. The ¥5,000 capsules contained a travel destination and a “mission” to be completed there. The system awarded 6,000 points that could be used to buy a round trip ticket to the destination listed.

“Some young people today have this feeling that they’d liketo travel, but they don’t know where to go, and want someone to decide for them. And some people these days can’t even choose what music they want to listen to. I think you could make a business out of using gacha to help people find new tunes. I want to give people this sense of discovery, like ‘Wait, what? What is this?!’ Real or digital, that’s what gacha is all about.”

(Originally written in Japanese by Kimie Itakura of Nippon.com. Banner photo: President Furuya Daiki of Kitan Club. All photos © Nippon.com except where otherwise noted.)