Manga and Anime in Japan Today

How Golgo 13 Creator Saitō Takao Changed Manga

Culture Manga- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Saitō Takao was an enormous influence on the manga industry, despite that fact that he never became the type of artist that garners critical respect, or at least, not the kind of acclaim that Tezuka Osamu, Shirato Sanpei, Tsuge Yoshiharu, or Mizuki Shigeru have. That was probably because he spent the majority of his over 60 years in the industry creating mass-market entertainment. For that reason, I felt that this article would be a good chance to look back at Saitō’s accomplishments in the world of manga.

Key Figure in the Gekiga Genre

Saitō was born in Wakayama Prefecture in 1936. After graduating from junior high school, he studied manga while working at his family’s barber shop. He made his professional debut at age 19 with Kūki danshaku (Baron Air). He found success in the period’s flourishing rental book market, and together with Tatsumi Yoshihiro and others founded the Gekiga Kōbō, a group of artists working dedicated to a new, serious style of comic—gekiga. Later, he became a central figure in the gekiga boom, which hit its peak in the mid-1960s.

That word, gekiga, identified comics intended for adults, covering mature themes in a more realistic style than the conventional children’s manga of the day. Saitō’s friend Tatsumi coined the term, but there is still no clear definition for it. If forced, I would say that cinematic visual expression with effective use of closeups or wide shots, as well as using more realistic drama in storylines, are the defining characteristics. However, it was Tezuka Osamu in his early period, rather than the gekiga artists, who first actively tried to use such techniques in manga. In that sense, you could see gekiga as both an “anti-Tezuka” movement, and one branch in the evolution that Tezuka brought.

There are also people who think of gekiga as using realistic, highly detailed drawings, but this is mostly because particular artists who used that style, like Saitō, Shirato, or Ikegami Ryōichi, gained particular popularity. Careful examination of works from other gekiga artists, including Tatsumi, Mizuki, or Tsuge, reveals that they do not universally reject traditional manga styles, particularly when it comes to character design.

For me, then, the only real way to draw any line between gekiga and manga is to judge whether the intended audience is adults or children. Of course, the earliest gekiga artists themselves said they were going to create a new form of manga that adults could appreciate. Saitō himself, whose name has become synonymous with the genre, was among those founders.

Varied Influences

As mentioned, the artistic form—the style of drawing—that Saitō chose to express the stories he wrote was based on realism.

Saitō discussed his artistic growth on an NHK television program back in September 2015. He said that in his youth he had wanted to make “manga like the movies,” with “realistic drama.” After considering just what the best style of drawing to do that was, he was drawn to nihonga—Japanese painting of the twentieth century combining traditional art with modern Western techniques—like he had studied in junior high school.

Undoubtedly, the line-art techniques nihonga uses to create a sense of realism, as opposed to the way Western art uses shadow to create three-dimensionality, is well suited to manga. Saitō also said that he liked book illustration—which you could consider an extension of his nihonga interest—especially the work of Naka Kazuya, who became famous for his illustrations of historical fiction by authors like Yamamoto Shūgorō or Fujisawa Shūhei.

At any rate, we can see this influence of nihonga and historical fiction illustration as another new element that Saitō brought to the world of manga, just like his interest in adult-oriented drama. For this reason, while actually following a methodology similar to that of Tezuka—whose goal in his early work was also “manga like a movie” and “realistic drama”—Saitō’s gekiga gave readers sense of something totally new, different from any comic they had seen before, particularly in visual expression.

Dividing Labor

However, drawing those realistic, highly detailed pictures took time. To address that, Saitō came up with a division of labor system by hiring a staff of multiple artists, and so established Saitō Productions.

This might seem like a standard practice now, particularly for modern manga artists working on strict schedules like those for weekly magazine serials, but it is safe to say that Saitō was the first to systemize it as a full-fledged business model. As an aside, some urban legends in the industry claim things like “Saitō only drew the characters’ eyes,” but in fact he drew all the important elements himself, including frontispieces, main character scenes, sound effects, and more.

What is also surprising is that not only did he have others help with the drawing, but the storytelling as well. As some readers may be aware, works like Golgo 13 credit a staff member charged with scriptwriting along with the drawing staff.

So, then, what exactly was Saitō’s role? It was storyboarding and composition. These tasks include laying out the comic panels, writing in the dialog, and roughly sketching out the manga itself, so it is in a way the most important work in producing a manga. To go even further, it is clear that Saitō wanted his role in comic production to be like that of a film director, particularly given his many references to wanting to make cinematic work.

In other words, as a manga artist Saitō directed his staff based on a belief that manga (gekiga) is not the work of a single auteur, but of a group of people with various talents. This led to the production of a large number of high quality entertainment works over such a long time—over 60 years!—with almost no breaks.

What is more, his greatest work, Golgo 13, not only earned Guinness World Records recognition as the world’s longest running single manga, now at 202 volumes, but it can continue after his death with a full staff of artists who carry his vision. In a way, this must be the ideal shape of the manga production system Saitō dreamed of.

Unwavering Heroes

Beyond Golgo 13, Saito is known for works like Sabaibaru (Survival), a story about life after a massive earthquake; Muyōnosuke, a revolutionary work of historical fiction; and the manga adaptation of Ikenami Shōtarō’s masterpiece series Onihei hankachō (Onihei’s Crime Files). But there simply is no room to list all of the work he has done, even just the biggest hits.

Basically, as mentioned above, all of his work was intended to be simple entertainment with mass-market appeal, and even if pieces feature complex international relations, their primary goal is easy reading without the need for deep thought. Of course, that does not mean that pure entertainment does not offer any other benefit. Indeed, anyone who reads widely of Saitō’s work is likely to learn something quite important.

For example, the protagonists of his gekiga continue to struggle to get through whatever terrible predicament they may be in and never give up—whether they strive for victory or mere survival—despite all their suffering. This quality unites both the assassin Golgo 13 and Suzuki Satoru, the young protagonist of Survival, who at first glance seem to be complete opposites.

There is one more trait that connects all of the protagonists of Saitō stories. No matter how the world around them changes, and no matter who they are dealing with, they do not waver in their convictions. They stay true to the end. For example, in chapter 353 of Golgo 13, titled “Jōhō yūgi” (Information Game), a massive organization tries to recruit Golgo as an asset. He refuses, saying, “I’m not looking for any permanent patrons, no matter how strong...”

The kind of unwavering lifestyle these protagonists lead can be a powerfully persuasive tool to help guide readers, particularly now that we all deal with the constant uncertainty of life in the COVID-19 age.

I interviewed Saitō in July of this year for my book Korona to manga (COVID-19 and Manga), and sadly it was one of his last chances to speak. He displayed the same unwavering spirit when he told me, “I have written my gekiga, particularly Golgo 13, without letting the common values or moral sense of the times influence me. Even in times like the present, when the international situation and Japanese society change so quickly, I stick to expressing my own feelings in my work. Even if gekiga ends up being a purely digital art, not on paper anymore, that won’t change. I refuse to let it.”

Whatever happens next, it seems that it is time to accept Saitō’s gekiga as telling truly timely stories.

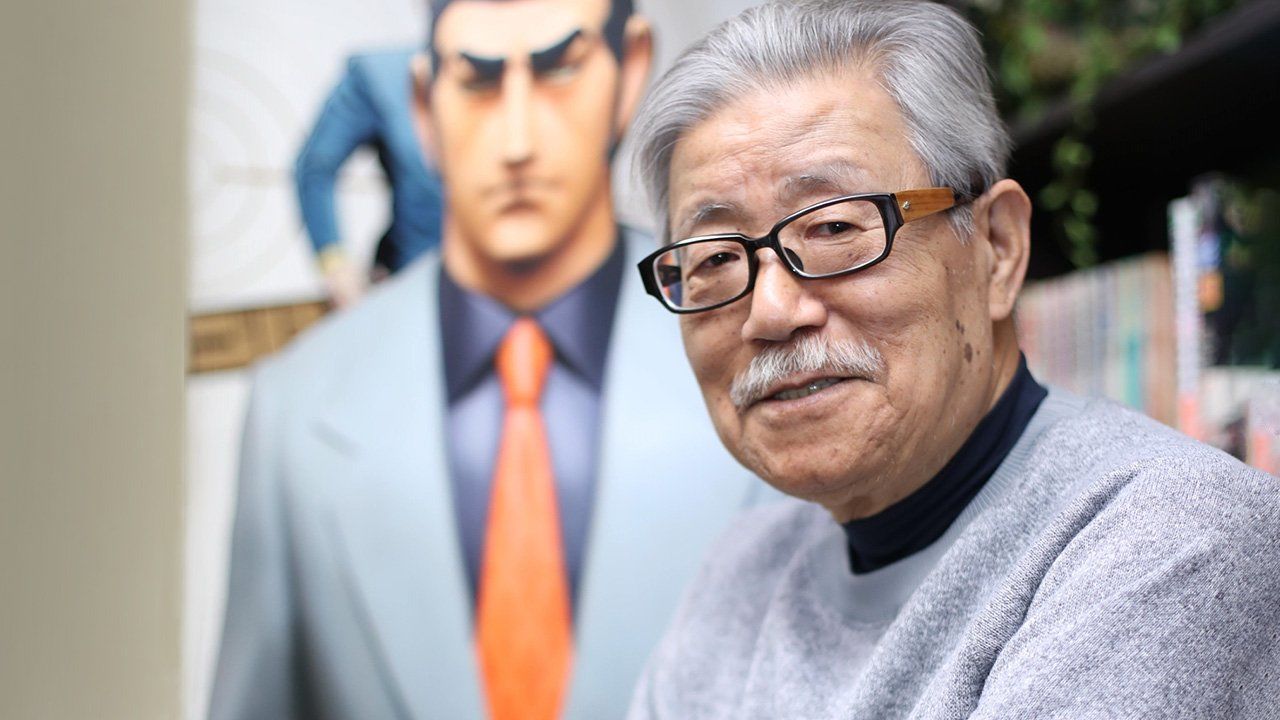

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Saitō Takao poses in his Tokyo office with a giant figure of Golgo 13. Taken February 5, 2018. © Sankei Shimbun.)