“Isekai” Boom Offers Better Lives in Other Worlds

Culture Society Entertainment Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Loser Heroes Reincarnated

In Japan, light novels (raito noberu) are a popular form of casual fiction aimed at young people, and many are adapted into manga or anime. Since around the 2010s, there has been a flood of stories in the isekai tensei (reincarnated in another world) genre. The website Shōsetsuka ni narō (Let’s Become Authors), has been influential in inspiring would-be isekai writers to the point that these stories are sometimes known as narō-kei (let’s-become style).

The isekai format is something like this: The story protagonist lives some kind of “loser” lifestyle here in the real world, working at a terrible job or unemployed, and often friendless. After some kind of fatal accident, a god or (frequently) goddess from another world summons the hapless character (usually by accident!) to that other reality. Most of these stories are set in a fairly standard sword-and-sorcery fantasy world vaguely resembling a fictional middle-ages Europe. Fans often call this Nāroppa, a narō-kei version of Europe.

It is safe to assume that the world in question will typically match the worldview of role-playing games like Dragon Quest or Final Fantasy, or Internet-based social-network games. There is magic and there are monsters. There are fantasy races like elves or dwarves, who can (of course) understand the heroes’ language and join their party. Defeating monsters allows the heroes to level up, and as they do so their strength, intelligence, luck, and other stats increase. They also learn new skills. And they tend to be romantically successful with all kinds of species.

As such, many isekai stories depend heavily on their readers being familiar with the basic conventions of video games.

Invincibility Cheats

One common feature of these isekai stories is some kind of special ability, commonly called a chīto, from the English “cheat.” The reincarnated protagonist is blessed by some divine power with an unmatchable ability that no other inhabitants of the other world (humans, elves, dwarves, or beastmen) have. One of the most common examples is the seichō (growth) cheat. A growth-cheat protagonist will earn 10 or even 100 times as many experience points from defeating a monster as another character would, soon becoming incredibly powerful. Most enemies are easily defeated, and injuries heal quickly.

A common variation on this pattern is when the main characters were “net game addicts” in their real-world life. They end up reincarnated in the game world of their addiction, and can quickly become invincible within it. Since they already know the locations of secret dungeons and monster weaknesses, they have a clear winning strategy from the start so level up quickly.

These characters grow strong without extended training or discipline, which makes progress much easier than a typical RPG, and also a bit unfair. The result is stories that are quick, satisfying, and thrilling to read. Popular YouTuber Seyarogai Ojisan once discussed his love of isekai on the radio, proclaiming that their greatest pleasure is “instant catharsis.” What a compelling idea.

Jackpot in the “Family Lottery”

Mushoku tensei: isekai ni ittara honki dasu (trans. Mushoku Tensei: Jobless Reincarnation).

Key works of the cheat-style isekai subgenre are probably Ainana Hiro’s Desu māchi kara hajimaru isekai kyōsōkyoku (trans. Death March to the Parallel World Rhapsody), Rifujin na Magonote’s Mushoku tensei: isekai ni ittara honki dasu (trans. Mushoku Tensei: Jobless Reincarnation), or Sogano Shachi’s Isekai meikyū de hāremu o (Building a Harem in an Otherworld Dungeon).

When I looked deeper, I came to feel that a sense of intractable inequality in modern society lays behind the desire for such cheats. There are people in this world who have had special opportunities from an early age, and have been coached in academics, sports, and the arts their whole lives. For more common folks, there is a feeling that no matter how hard they try, they can never catch up with the privileged few.

In recent years, this inequality has birthed terms like “parents gacha” or “DNA gacha,” likening this genetic lottery to the gacha vending machines that dispense random toys, or the mechanics named after them for distributing random items in video games. There must be many who recognize that the luck of one’s birth and homelife can lead to inequality.

But in isekai stories, our protagonist starts out with the biggest jackpot of all.

Slow Living for Free

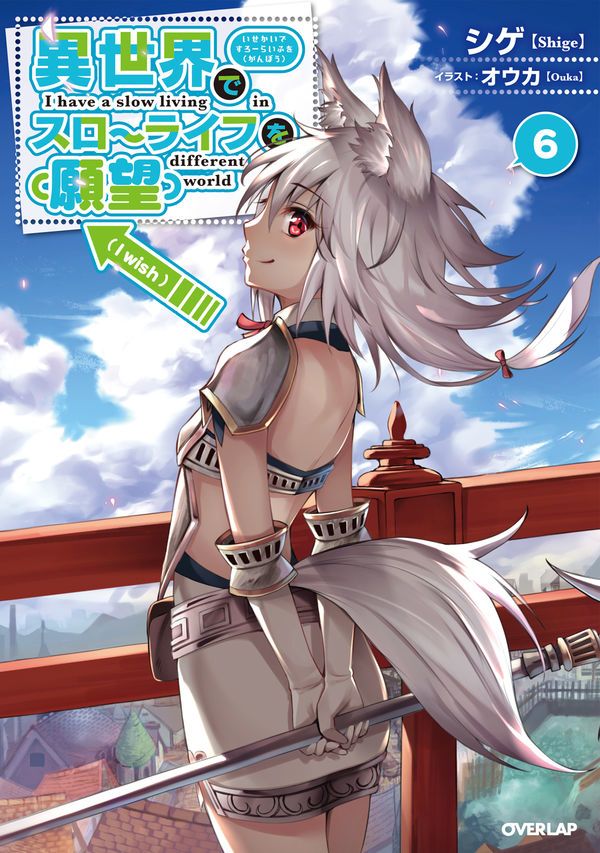

Isekai de surōraifu wo (ganbō) (trans. Slow Life In Another World (I Wish!)).

As these cheat-style isekai stories reach mass-production levels, other forms of narrative have branched off to meet different desires. One example is the “slow living” isekai subgenre.

Recent years have seen an increase in stories in which, instead of reincarnating and becoming a hero or sage and defeating the dark lord, the protagonists live out their dream of settling down in a remote area and starting a farm, or relaxing in a peaceful village. Of course, these being isekai stories, the easy-going protagonists are naturally gifted with some extraordinary ability, becoming the village’s great defender when it is threatened by monsters or bandits. It is a pattern based on hidden strength.

Slow living and semi-retired life are really quite popular in the real world, but they both require a certain amount of starting capital. And, of course, farming is no easy task, village life is often inconvenient, and rural areas can be intolerant of outsiders. But none of those issues matter in the isekai, and the dream can be lived stress-free. If problems do arise, then surely there will be a quick magical solution.

Important examples of slow living isekai are Shige’s Isekai de surōraifu o (ganbō) (trans. Slow Life In Another World (I Wish!)), Okazawa Rokujūyon’s Isekai de tochi o katte nōjō o tsukurō (Let’s Buy Some Land in Another World and Start A Farm), or Watanabe Tsunehiko’s Risō no himoseikatsu (trans. The Ideal Sponger Life).

Breaking the “Villainess” Trope

So far, I have mostly discussed works with male protagonists, but there are also huge numbers of isekai novels with women in the lead, where they are reincarnated in the world of otome (romance simulation) games. However, these women are often reincarnated not as the games’ heroines, but rather the antagonist—the evil villainess.

Yamaguchi Satoru’s Otome gēmu no hametsu furagu shikanai akuyaku reijō ni tensei shite shimatta (trans. My Next Life as a Villainess: All Routes Lead to Doom!) or Reia’s Kōshaku reijō no tashinami (trans. Accomplishments of the Duke’s Daughter) are major examples of this story.

Kōshaku reijō no tashinami (trans. Accomplishments of the Duke’s Daughter).

For these villain-reincarnated protagonists, if the story proceeds as it normally would, they are destined to a bad end—losing their engagement with the prince, or watching their noble family’s fall from grace. The heart of these stories, then, is seeing how they break free from these standard villainess tropes.

With male protagonists, the popular stories are about becoming invincible and defeating enemies with ease, but for women-led stories the outcome hinges on using cleverness and hard work to escape a scripted bad outcome, and finding some measure of gentle happiness.

Many of these villainess stories feature a protagonist who does, in fact, get the bad ending once. She then returns to her childhood, where she regains her memories of the real world and realizes that she is in the world of an otome game she played. And, of course, that she is now the villain of the story. She repents of her past life as a self-absorbed princess, studies hard, gathers a band of talented companions, and starts farming and reforming how she rules her domain. All this hard work wins the protagonist love from both men and women, while the prince who would have eventually broken off their engagement in the bad end is preemptively rejected.

I think the twisting of conventions reflects women’s desires for independence. The characters use real skills in economics and management to revitalize their domains. In other words, they find a career to help them lead a solid, adult life. They also need to be popular to escape from their destiny as a villainess, and so these protagonists tend to cultivate a personality that is attractive to all. In recent years, dōsei mote (same-sex popular) and onna mote (girl-popular) have become keywords in women’s fashion magazines, so that idea is in step with current trends.

Reading isekai stories can offer a huge variety of experiences: the chance to beat your chest and proclaim Ore tsueee (“Me strong!” in Japanese gamer slang), lead a quiet life in the countryside, or savor the pleasure of looking down your nose on those who sought to betray you.

At first glance, the stories and settings might seem ridiculous, but in truth they are rooted in authentic desires, and can even help us forget the helplessness of daily life for a while. Isekai reincarnation stories fulfill desires to be reborn somewhere other than here, and to become something special, if only for a short while. Isn’t that the true secret behind isekai popularity?

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Pixta.)