Murakami Haruki and Stan Getz: Twin Exemplars of the Art of “Cool”

Culture Entertainment Music- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

An Intimate Connection with Jazz

Murakami Haruki is a true music lover. Music permeates his life and work, and seeps naturally into his prose. Music—and jazz in particular—is essential to any discussion of his work. His writing is inseparable from his love of jazz. In that sense, it might be more appropriate to speak of “listening” to Murakami’s work rather than simply “reading” it.

The words he writes seem always to come with musical notes attached, his prose accompanied by constantly shifting melodies. A steady bass line beats out the rhythm, while the piano, trumpet, and other instruments riff on the melody. These musical characteristics make his prose easy to read, helping to pull readers into the story. Before you know it, you are hooked, longing to know what happens next. Other elements of music, including harmony and tone, have also had a major influence on Murakami’s style.

But readability does not imply light and insubstantial subject matter. In fact, Murakami’s works often grapple with rather gloomy and serious topics. Certainly, they do not come with any feel-good guarantee that they will lift the reader’s mood. The same thing can be said of jazz. Anyone with even a nodding acquaintance with the history of the genre will know something of the repression and struggle that underlies the music and the lives of many of the people who made it.

The history of jazz is indelibly marked by the brutal reality of slavery and its aftermath: callous cruelty on one side, and a long struggle for justice on the other. For generations, enslaved African Americans longed for their freedom. Jazz takes this journey and puts it into musical form. Through the birth of the blues, and its evolution into jazz, the music sung and played by the slaves and their descendants was a vital part of their attempt to overcome their cruel fate and find a road to freedom.

The people who were taken from Africa and their descendants in the Americas were forced to live lives of almost unimaginable cruelty and injustice. But the injustice did not end with liberation, and they are still not truly free, despite superficial appearances. Many people around the world continue to struggle with invisible discrimination and oppression. Often, they have no choice but to thrust their suffering to the back of their minds and press on with their lives in silence. Perhaps the biggest challenge we face is to find a way to break out of the solipsistic, withdrawn state into which so many people have fallen. Freeing yourself from invisible bonds—this is a major theme of Murakami’s work. The search for a path to individual freedom shares a lot of common ground with the aims of jazz. It is fair to say that Murakami’s work is marked by a “jazz” sensibility both in terms of his style and of the major themes of his work.

The Weighty Themes that Lie Beneath the Light Surface

Of all the many jazz musicians who helped Murakami develop his distinctive style, one stands out in particular: cool jazz saxophonist Stan Getz (1927–91), who leaped to international prominence with the release of the Getz/Gilberto LP in 1964, containing his classic recording of “Girl from Ipanema.” Getz’s records were marked by a new kind of cool, marked by a certain distance that set him apart from the “cool” of the black musicians in whose footsteps he was following. What was it about his style that captured Murakami’s imagination and made him a lifelong fan?

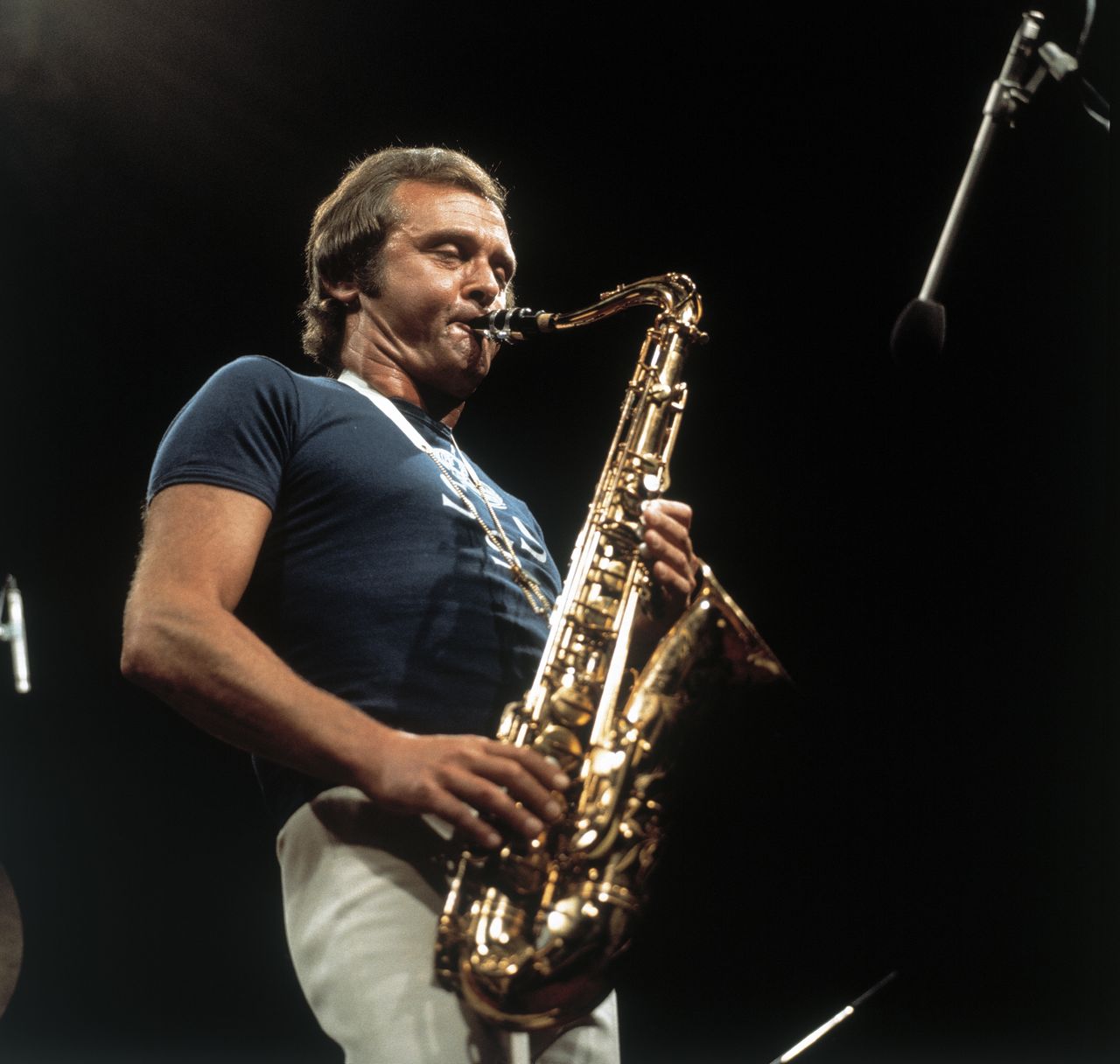

Stan Getz, one of the pioneers of “cool” jazz. Murakami Haruki learned a lot from his approach to his art. (© Aflo)

For one thing: there is nothing pushy in Getz’s music. His performances do not grab you by the throat and say: “Sit down and listen: this is jazz!” He had a light, lyrical sound that spoke directly to the emotions. Through the sound of his tenor sax, he was trying to tell the listener something, and there is no doubt that Murakami picked up on this message at an early stage. It is a truism that jazz soloists “tell a story” through the language of music. In Murakami’s case, it is no exaggeration to say that he successfully entered into a dialogue with Getz, and that this has had an immeasurable influence on the development of his own distinctive prose style.

Murakami’s writing shares something of a “magical touch” with Getz’s cool musical style. His writing hooks readers with its catchy, musical style. Every word in his stories is there for a reason. There are no wasted words in his writing. His stories are free of tedious sections that the reader must slog through to get to the interesting parts. He grabs readers with his distinctive prose style, and draws them into his fictional world, leading them on to the social or historical problems that lie below the superficially harmonious surface of his stories. Beyond that, he gets readers to commit an experience of a kind of collective subconscious that goes beyond individual experience. Murakami pulls all this off like a magician—using the tools and methodologies of the art of fiction.

Distance, Aloofness, Cool

Jazz is known as an improvisational art. For this improvisation to be possible, the players need to have a thorough knowledge and understanding of the language of music. Getz absorbed the rules of this language at an early age, so that it became second nature, enabling him to improvise melodic lines of genius and beauty. Murakami has a similar understanding of the rules and grammar of the language of fiction, acquired through a lifetime of voracious reading. As with Getz, it is this deep understanding of the rules of his chosen art form that allows him to compose his improvisational prose. In jazz, improvisation is not something that can be prepared: it has to come naturally out of the inspiration of the moment. In the same way, Murakami allows his writing to pour out of him, guided by his artistic instincts the feelings of the moment. He completes his pieces later by a repeated process of editing and polishing. This approach may be another thing that he learned from Stan Getz and his other jazz heroes.

Even if he was not a revolutionary like Miles Davis and John Coltrane, Stan Getz was a musician with his own distinctive style. Although he was inevitably influenced by other musicians, he was never content merely to imitate his models, but always sought to create something new. He hated imitation. He wanted to come up with his own unique Getz sound. Just because jazz was originally an African-American artform, there was no sense in simply trying to copy black musicians. He knew that unless he could develop his own style, his music would never be more than meaningless imitation. Perhaps it was this realization that led to the subtle sense of distance that marks his music: a coolness and distance that came from Getz’s feeling of apartness from the black musicians who had inspired him.

This attitude is another thing that he shares with the author. Murakami too has never been content merely to imitate his predecessors, but has always looked to create a new style of language and writing that suits the times. Following Getz’s example, Murakami has gone beyond the framework of preexisting Japanese literature to create his own world, believing that it would be impossible to write about contemporary society using the style of a writer like Ōe Kenzaburō, for example. He set about creating his own fictional world, just as Getz developed his own style by following his heart. Readers identify with the distance and “cool” that result from this approach, and are often inspired to realize that they too can choose the lives they want to live. Indeed, this may be the biggest attraction of Murakami’s writing for his millions of readers around the world.

A Message of Hope

Something of this sense of apartness may have come from Getz’s background. He loathed racial prejudice and discrimination. He was not black, but he didn’t belong to the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant background of mainstream America either. He came from a Jewish family that traced its roots to Ukraine. This put Getz in a slightly anomalous position in American society, and in the world of jazz in particular. It was an in-between position, belonging neither to one world nor the other. And for this reason, he was able to look at both sides in a neutral, dispassionate manner. This ambiguous perspective gave him a feeling of aloofness and distance, and helped to produce his unique tone. Being Jewish cannot always have been easy in an American society where the undercurrents of prejudice still ran strong. Consciously or unconsciously, I think these social prejudices must have had an influence on his music.

Something similar can be said of Murakami: the way he has chosen to live his life has inevitably placed him at a distance from mainstream society. Unlike most normal students, he did not get a corporate job after graduation university. Nor was he content with simply being a jazz fan: while still a student, he opened a jazz bar in Tokyo, which served as a place for people to come together to listen to jazz records and enter into a dialogue with the music.

Jazz kissa like this were a common sight in Japanese cities in the postwar era, when imported jazz albums were an expensive luxury. Young fans used to gather instead at specialized cafes where they could listen to records for the price of a cup of coffee. It is a far cry from today, when young people can listen to music for almost nothing. Murakami’s café/bar was a slightly later version of this cultural phenomenon of the postwar years. The young Murakami rarely chatted with his customers, preferring to stand apart, his mind on the music. Even after he closed the bar and started his career as a writer, jazz continued to be a constant presence in his fictional world.

I sometimes feel that we can read in Murakami’s work a message for the many people living isolated and lonely lives in today’s atomized, inward-looking society. Jazz music values individuality: the soloist steps forward and expresses himself as an individual, even while continuing to play as part of a group with other musicians. I think we can detect a similar message in Murakami’s work, which seems to call for a shift away from an excessive focus on the group to greater freedom for the individual. Murakami opens his readers’ eyes to the importance of being true to themselves and living their lives as they really want to live, instead of burying their individuality beneath the weight of social convention and tradition. “Now’s the time: Let’s bring more jazz into our lives:” This is the quiet message of encouragement I always seem to hear whenever I read his work.

(Banner photo: Murakami, third from left, poses with three legends of Japanese jazz—from left, Watanabe Sadao, Ōnishi Junko, and Kitamura Eiji—at a recording session for an episode of his “Murakami Radio” program, for which he acts as DJ. on June 26, 2019, at Tokyo FM in Chiyoda, Tokyo. © Jiji.)