Becoming an “Otaku”: How I Learned Japanese from Anime, Manga, and Music

Lifestyle Culture Anime Manga Language- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Growing up with Japanese Pop Culture

I am an otaku.

To tell the truth, I feel slightly hesitant about claiming this status. I am far from an expert on the two-dimensional world of manga and anime characters, and part of me feels that I am being disrespectful to the true otaku by claiming membership in their community. But then, as “ordinary” society looks down on otaku, stating such concerns seems to show that I qualify sufficiently, so I will continue to call myself one.

I did not realize it till later, but when I was a child growing up in Taiwan, myself and the other children around me lived through all the same crazes and watched the same anime as children our age in Japan, and more or less at the same time.

From my first years in elementary school I used to enjoy reading the manga Mei tantei Konan (Case Closed), my imagination captured by the battles between the hero Kudō Shin’ichi and the sinister Black Organization—even though I couldn’t read any of the hiragana and katakana characters that sometimes cropped up in the story as clues. When I was a bit older, we all became obsessed with Corocoro Comics, and I collected all the latest toys from Japan, including Mini 4WD cars, B-Daman, Hyper Yōyō, and Beyblade. In high school, I discovered the joys of Cardcaptor Sakura manga series, and became hooked on the manga series Inuyasha (A Feudal Fairy Tale).

The thing I loved most of all was Pokémon. I could not read Japanese at all in those days but that did not stop me from playing the games and I made sure never to miss one of the weekly episodes on TV (except when my parents got in the way). I collected Pokémon toys and merchandise and checked out all the movies and video and DVD releases. I remain convinced to this day that the first movie Myūtsū no gyakushū (Pokémon:Mewtwo Strikes Back!) is a true masterpiece.

In fact, I must have heard about the craze for these “pocket monsters” even before the franchise officially landed in Taiwan. I remember one day when I was in the early grades of elementary school, just learning to read, when my attention was caught by a headline on a newspaper in the local convenience store containing the intriguing word “pocket monsters” in Chinese. The article turned out to be a report about a controversial event in Japan, where hundreds of children had been rushed to hospital after suffering epileptic seizures while watching a popular new anime on TV: the notorious thirty-eighth episode of the first series, “Denno Senshi Porigon” (Cyber Soldier Polygon). The controversy created a major stir in Taiwan, as the “Pokemon shock” caused reverberations around the world.

At that time, I had not yet seen the anime myself. It was not until several years later that the series started to run on Taiwanese TV. The first episode I saw happened to be Episode 31, “Diguda ga ippai” (Dig Those Diglett!). I was immediately hooked. I quickly caught up with the back story by reading the comic book version of the series, and continued to watch the anime avidly until I entered high school. For obvious reasons, the notorious episode 38 was never shown in Taiwan, and was not included in the comic version either. For many years, it remained an unknown mystery episode for me: often talked about, but never seen.

Learning Japanese by Singing Anime Songs

Otaku culture has been a constant companion on my path to learning Japanese. I grew up in a provincial town where there weren’t any Japanese teachers, so took my first steps in learning the language on my own when I was about 13 or 14. The first kana syllabary I learned was not hiragana but katakana. That was the script the Pokémon characters’ names were written in. My knowledge of English helped me here, as a lot of the Japanese names were inspired by English words.

My biggest help in learning hiragana came from anime songs. As a digital native, my first step was to go online, where I found a chart showing the 50 sounds of the hiragana syllabary with their pronunciation given in alphabetical romanization. I downloaded the video for the Pokémon theme song and typed the Japanese lyrics into a Word file as they showed up on screen, looking them up on the chart and matching them against the rōmaji pronunciations.

Whenever a kanji came up, I would type it in Chinese. Then I printed out my homemade lyrics sheet and started singing along. Before long, I had memorized most of the hiragana characters. I picked up the Japanese pronunciations for some of the kanji in the lyrics, learning words like “kimi” 君 (you), “suki” 好き (like), “shōnen” 少年 (boy)、and “monogatari” 物語 (story). I started to watch anime in the original version rather than dubbed into Chinese, and fell in love with the sounds of the Japanese words.

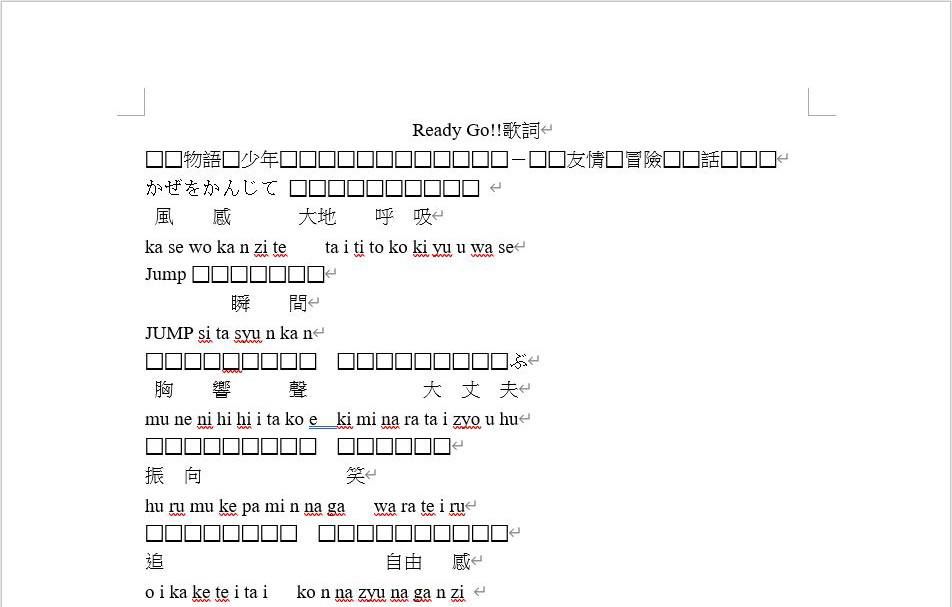

A lyric sheet I made not long after I started to learn Japanese, showing the words to an anime song. Actually, if you look closely there are quite a few mistakes! (Courtesy Li Kotomi)

As my level improved, I tried my hand at other anime songs, including the theme tunes for Case Closed, Inuyasha, and Hikaru no Go. It was around this time that I encountered other songs by Kuraki Mai, V6, and Dream, all of which made a huge impression on me. Even if I did not understand the lyrics, I could sing along easily enough by following the pronunciation of the kana. This was somewhat puzzling itself: even though I knew much more English than Japanese in those days, I struggled to sing English songs, and spent all my time singing Japanese songs. In the process, I picked up all kinds of new words. In those days, my Japanese vocabulary was much stronger than my grammar. But I had a fairly agile mind and a good memory, so even without anyone to teach me, once I had learned a word like “kasumu” (to become hazy) for example I could immediately associate it with the character Kasumi in Pokémon and figure out what it meant. In this way, I gradually built up my own idiosyncratic picture of the language and how it worked.

It was a little later, after I started attending high school in the city, that I came into contact with what I would call “full-on” otaku content—anime like Shakugan no Shana, Suzumiya no yuutsu (The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya), and Lucky Star. These anime and others were another major source of inspiration. Alongside my regular classes, I started to attend private lessons once or twice a week, finally receiving structured tuition in Japanese to supplement the ad hoc course of self-instruction I had been following until then. I was teased and scorned at school as a nerd and otaku, but there is no doubt in my mind that immersing myself in anime like this was a major help to me in my studies. I continued the practice even after entering university, watching these anime and writing down the lyrics to songs I liked. Studying the language in this way helped my hone my skills in both listening and writing.

Like any otaku, I have naturally visited a maid café in Akihabara, where the maid wrote my name on my omuraisu (omelet with fried rice).

My Jewelry Box of Words

As my Japanese improved, I gradually came to feel that J-Pop and ordinary anime songs were no longer meeting my needs. The lyrics of J-Pop songs all seemed to consist of the same repeated words and phrases, as if they had been assembled by template from the same limited stock. The grammatical structures were limited too, mostly drawing on sentence patterns that a student would be expected to master before reaching level 3 of the Japanese Language Proficiency Test (under the old system). I wanted to enrich my vocabulary, and these songs with their meager lexicon started to lose their appeal. It was around this time that I encountered Sound Horizon.

The group’s music exposed me for the first time to the full riches of Japanese vocabulary. Their lyrics contained many new kanji and terms, and regularly featured the sentence patterns I was studying at levels 2 and 1 of the JLPT. With every song I heard, I experienced the joy of immersing myself in a flood of new words, and my vocabulary soon became richer and far more nuanced.

Probably some people would laugh at some of the words I scrupulously noted down and painstakingly committed to memory. They might well ask when I would ever use them. But I like to think of my store of words as a jewelry box: I believe that it is always a good idea to keep as many jewels in my collection as possible. Some of them might not be perfectly round, and many of them will not be suitable for just any occasion. With some of them, it might not be obvious how they could ever have any value. But they all shimmer and glint in the moonlight when the right moment comes. In fact, it was thanks to the rich stock of words I built up in these years that I was able to become a writer in Japanese.

I have my own little theory about writing. People often claim that the best writers are those who can express deep ideas in simple language that anyone can understand. I am not sure I agree. A writer is like a deep-sea fish, a dweller of the deep who swims freely across wide oceans of words; if that fish is confined to a small, shallow pond, it will be stifled for air and quickly die. The more linguistic tools a writer has at her disposal, the better, as far as I am concerned.

The simplest ways of saying things are not always the most vivid or concise, at least in writing. Why write of a “narrow place where movement is restricted” when you could describe it as “cramped”? Surely it is helpful to be able to say that you are jaded, satiated, weary, or fed up to the back teeth with something, rather than always having to say you’re simply getting “tired” of it? Every language has its own rich stockpile of phrases and words, each with their own nuances and resonances. Part of the challenge and enjoyment of being a writer is finding the word with precisely the right meaning and nuance for the context. In sewing, you do not always want the plainest thread; when necessary, you might choose to use expensive gold thread. It is the same with writing. I do not mind using recondite or recherché kanji compounds if I decide that they will suit my purpose and help me make my piece the best it can be. I can understand the argument that politicians need to use accessible language to ensure that their message reaches a broad spectrum of people. But I am not a politician.

The truth is, there is no such thing as “language that anyone can understand.” I know from personal experience that the people who insist stridently that writers “use language that ordinary people can understand” are often the very same people who unthinkingly exclude many individuals from their definitions of who constitutes “anyone”—people like my younger self 10 years ago, for example, when I still could not read or write Japanese fluently. Their concept of “anyone” is bogus: I prefer to write for readers who are prepared to follow me in what I write. If I have gone to the effort of sourcing the best ingredients I can find and have spent hours in the kitchen preparing a complicated meal, I think it’s reasonable to hope that my readers will take the time to savor it properly, even if it sometimes means they need to keep a dictionary handy. I am not a native speaker, after all, so there is a limit to the amount of “difficult” words I am likely to use. I still follow the same acquisitive habits today, ravenously reading Japanese novels every day. An almost incredible universe of words exists out there that I still do not know, all of them quietly waiting for me to discover them . . . at least that is the way it feels.

But enough with the digressions . . . let me get back to Sound Horizon and the music that really helped my Japanese ability to take off. It wasn’t until a bit later that I learned this, but their music is often regarded as exhibiting many of the symptoms of the social condition known recently as “chūnibyō” or “junior high school second grade disease.” This condition affects children in the eighth grade: precocious types whose urge to stand out is so pronounced they sometimes convince themselves that they are artistic geniuses or have special powers.

My own introduction to the concept came from an anime, not surprisingly—the classic series “Chūnibyō demo koi ga shitai!” (Love, Chunibyo and Other Delusions). This series introduced me to the jakigan or “evil eye” type of chūnibyō—in which adolescent goths create a world of make-believe in which to live out their fantasies. Their conversations are sprinkled with literary and philosophical terms, they refer to themselves using outdated literary first-person pronouns, and they are given to talking mysteriously about concepts like ‟purgatory“ and ‟Schrödinger’s cat” and reciting strange incantations and magic spells.

My first trip to Okinawa was as part of a Sound Horizon fan club tour.

Pretentious or Appealing?

Characters exhibiting chūnibyō symptoms are a frequent occurrence in the two-dimensional world of anime and manga these days, and I have met people like this in the real world too—both Japanese and foreign students. In general, these characters seem to strike people as pretentious and embarrassing, but personally I find them rather endearing. Ultimately, their eccentric behavior is the result of an inability to control the burgeoning sense of self and the urge for creativity and self-expression that comes with adolescence. Certainly I find the chūnibyo characters a thousand times more likeable than some of the other forms of neurosis we see prominently displayed in our everyday society, where many people reach adulthood with their overblown sense of ego still not tamed and brought under control—including the desperate-to-impress businessman with his showy fondness for the latest corporate jargon, who likes to throw around English business terms he does not really understand, like “consensus,” “commitment,” and “issues.” Or the etiquette mavens who have no particular knowledge about language but are already ready to rebuke sternly anyone who dares to break banal and fiddly “rules” of usage and office honorific language without any good evidence to support them. Give me someone with chūnibyō any day over these people.

Come to think of it, I was in the second year of middle school myself when I started to learn Japanese and started to write. One of the classic symptoms of the condition in Japan is for teens to announce that they have grown out of J-Pop and refuse to listen to anything but American and British groups. The symptoms were slightly different for me, growing up in Taiwan. I tired of songs with lyrics in Chinese and started to listen exclusively to Japanese songs. In other words, although the term did not yet exist back then, I was probably a bit of a chūnibyō sufferer myself, struggling to keep my surging sense of self under control, and looking for an outlet for my pent-up feelings and creativity. By throwing myself into studying a foreign language, writing stories, and eventually becoming a writer, I succeeded in sublimating my yearning for meaning and self-expression. To put it another way, it may be no exaggeration to say that my own bout of chūnibyō became a foundation of creativity.

So my advice to young people around the country—indeed, around the world—who might be diagnosed by those around them as showing all the signs of chūnibyō: don’t be ashamed of your symptoms. Regard them as a gift, and cherish them with pride. They might just help you find yourself and grow up to be who you really are.

(Originally published in Japanese and Chinese. Banner photo: © Carlos/Pixta.)

Related Tags

Narita Express Keisei Skyliner Japanese language otaku anime Taiwan