Manga and Anime in Japan Today

Gundam at 40: The Influential Anime Series that Redefined a Genre

Culture Anime- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

This year marks the fortieth anniversary of Mobile Suit Gundam. Since its debut in 1979, the anime series has entertained fans and inspired them to look toward the stars. One such example is a project involving the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency and the University of Tokyo that aims to launch models of the mobile suits into orbit to help boost excitement ahead of the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games in 2020.

From left, astronaut Kanai Norishige, Olympian Murofushi Kōji, Gundam director Tomino Yoshiyuki, and University of Tokyo professor Nakasuka Shin’ichi at a press conference in Tokyo announcing the One Team Project in May 15, 2019. (© Jiji)

How did a humble Japanese mecha anime show become a cultural icon? Below I explore the vision of Mobile Suit Gundam and the influence the series had on young fans of Japanese animation.

An Evolving Industry

Early in its history, Japanese animation was largely regarded as children’s entertainment. This perception continued even after the industry became more established through the success of Tezuka Osamu’s Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy), which first aired in 1963. The television debut of Ūchu senkan Yamato (Space Battleship Yamato) in 1974 and release of a feature film in 1977, however, showed that anime could explore complex storylines aimed at older audiences. The series was a runaway hit with young adults and became a social phenomenon, pushing the industry toward richly animated works with intricate plots.

Even as anime evolved, though, it struggled to distinguish itself from manga. Much of the industry output was adaptations of well-known comic titles, leading to the perception that manga studios were running the show. In 1978, the launch of anime-focused magazine Animage helped dispel this idea by providing the growing throng of Japanese fans a behind-the-scenes look at the production process. Writers detailed the specific story-telling methods and visual techniques that went into creating works, helping define the genre. Production companies poured energy into innovative narratives, and the industry flourished as the burgeoning fanbase clamored for new and ambitious works, producing a perfect environment for an anime like Mobile Suit Gundam when it appeared on the scene in 1979.

Gundam was the effort of a small production team that included series creator and director Tomino Yoshiyuki, character designer and anime director Yasuhiko Yoshikazu, and mechanical designer Ōkawara Kunio. Unlike much of the animation on television at the time, it was not an adaptation of a novel or manga but a completely original story. After hitting the airwaves, the series rapidly attracted a loyal legion of fans who tuned in each week to get lost in a purely anime spectacle. Far from passive viewing, Gundam dazzled viewers visually and challenged their intellect with complicated plot twists.

The popularity of the series was helped along by the proliferation of videocassettes during the 1980s. As more and more households owned home video recorders, viewers would record and repeatedly watch episodes to work out the intricate storyline or loan the cassettes to friends. For many, Gundam became synonymous with Japan’s transition into a new age of visual technology.

Robots and Realism

In June of this year, a retrospective opened at the Fukuoka Art Museum that illustrated Tomino’s role as the creative driving force behind Gundam’s intricate anime universe. The extensive exhibit revealed how the simple premise of selling toy robots to children freed Tomino to develop the story as he saw fit. Just as long as the toy models turned a profit, he had a blank slate on which to pour out his artistic talents, a rare opportunity in the industry, and one that he took full advantage of.

Mobile Suit Gundam creator and director Tomino Yoshiyuki. (© Jiji)

Tomino set out to redefine the mecha anime genre. Most works up to then stuck to the standard trope of giant humanoid machines designed by scientists to defend human society from mysterious alien aggressors. The massive robots at the heart of these stories were treated as little more than high-tech weapons, an idea that Tomino questioned.

Taking inspiration from American physicist Gerard O'Neill, a leading proponent of space colonization, Tomino set Gundam in a world that, given the steady march of technology, viewers could imagine existing in the not-far-off future. Instead of distant galaxies and alien invaders, the opposing forces were humans who plied the ether between the earth, orbiting settlements, and lunar colonies, doing battle in giant machines Tomino christened “mobile suits” to distinguish them from their robot predecessors.

By weaving threads of realism into the story—touches of true science like O’Neill’s theoretic space colonies—Tomino imbued the visual appeal of Gundam with a crucial touch of plausibility, an aspect of the series that viewers found compelling.

Hope in War

Another of Tomino’s innovations was the Universal Century timeline that serves as the historic backdrop of the narrative. The story takes place in an imaginary age of space colonization during a conflict known as the One Year War. However, Tomino gave viewers a clear sense that they were witnessing events along an uninterrupted chronology that stretched from the distant past into an undetermined future, lending the series an almost epic feel that has been key to its enduring popularity.

Even after the anime finished its television run, the world of Gundam continued to expand in the minds of fans. Enthusiasts snapped up newly released detailed plastic models of the mobile suits—these carried the year UC in which they were in service, perpetuating the storyline—personalizing the figures with custom paint jobs and other details. Tomino also released a manga and novel based on the original anime that further fleshed out details of story.

A Gundam RX-78-2 HGUCI 1/144 scale model released by Bandai in 2015 for the thirty-fifth anniversary of the series. (© Jiji)

There is no question that the originality of Gundam enabled the world that Tomino created to expand far beyond what he initially imagined. Fans were free to envision events outside those portrayed in the original television series, following flights of fancy into realms of their own design. However, one key facet that continues to attract successive generations to the series is that at its heart, Gundam is a simple coming-of-age story. Each episode follows the innocent, teenage protagonists Amuro Ray as he confronts senseless death and destruction and the undue demands of society; one moment he is lashing out emotionally and the next discovering deep-felt bonds with his comrades as he battles for the fate of the world.

As the story progresses, though, it offers a glimmer of hope that humanity can escape its seemingly endless cycle of war and destruction and transition into a new age of peace, cooperation, and understanding. Amuro and other so-called newtypes, humans who have developed superior mental powers to withstand the rigors of life in space, are at the center of this idea, their evolved minds symbolizing the potential to alter the course of fate. The faint hope that mankind will change its ways hovers like a distant star over the violent scenes of mobile suits locked in battle that make up much of the series.

Amuro Ray (center) flanked by characters from Mobile Suits Gundam in a still image used during the ending credits of the show. (© Sōtsū/Sunrise)

Amuro is an engaging character, and the story of his exploits, told in a seemingly documentary style, make Gundam a compelling narrative of youth. However, as the hero battles his adversaries, viewers can sense that the conflict is not gratuitous, but that he is fighting to change his circumstances. The idea that, armed with hope, humans can reach their full potential is perhaps the most endearing message of the series and what has supported the franchise through its various incarnations. Gundam was the first anime of its type to offer such an intricate, thought-provoking structure, and its themes continue to ring true even after four decades.

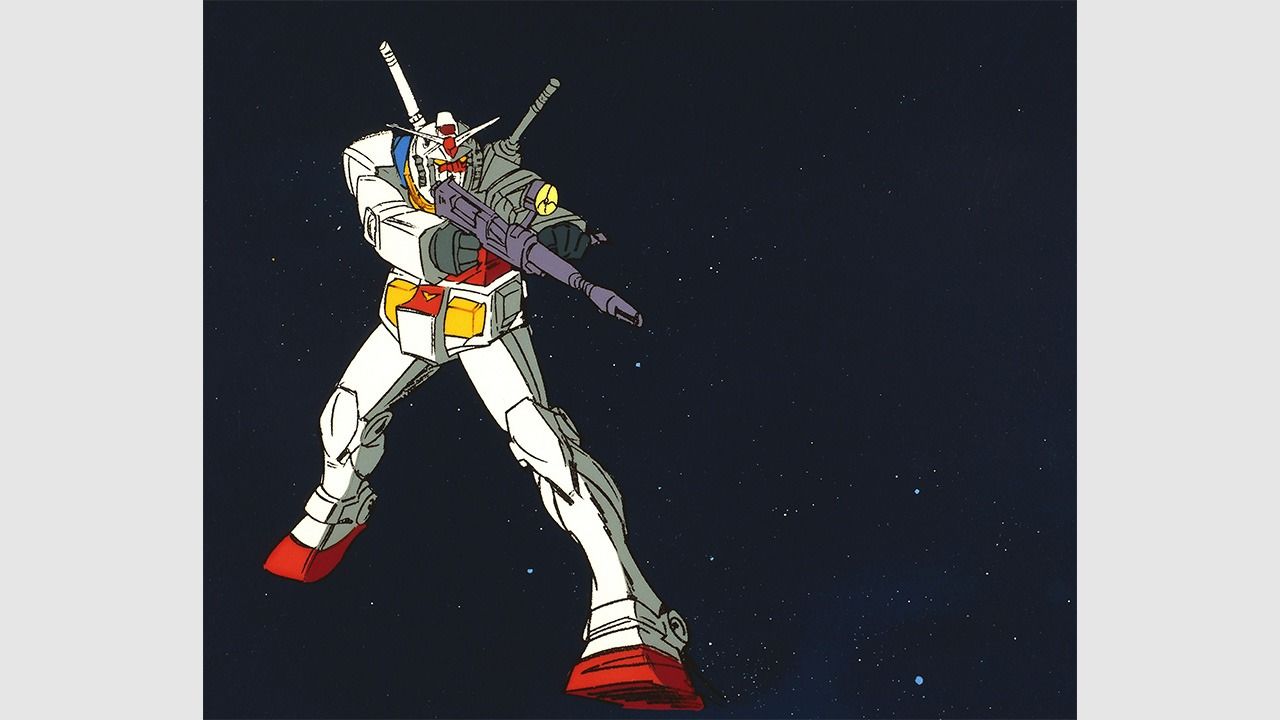

(Originally written in Japanese. Banner photo: Gundam trains its beam rifle on the enemy in a scene from episode 2 of the series, “Destroy Gundam!” © Sōtsū/Sunrise.)