British Museum Exhibition Provides “a Manga for Everyone”

Culture Arts- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The British Museum’s upcoming manga exhibition, running from May 23 to August 26, 2019, can boast several firsts. The Citi Exhibition Manga features around 70 manga titles and some 50 artists, making it the largest ever collection of manga displayed outside Japan. It will be the first Japan-related exhibition to occupy the museum’s prestigious Sainsbury Exhibition Galleries. And it will be the first British Museum exhibition centered on living artists.

It also comes at what the exhibition’s lead curator, Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, calls a “Japan moment.” As well as taking place during the run-up to the Rugby World Cup in Japan this year, and the Olympics and Paralympics in Tokyo next year, the exhibition will be an inaugural event in the Japan-UK Season of Culture 2019–20.

The exhibition will target a younger demographic than usual for the British Museum, says Rousmaniere: “Generation Z,” the generation following the Millennials. Yet it will still be accessible to people of all ages, including the British Museum’s patrons and supporters, many of whom are in their fifties and sixties. Rousmaniere stresses that no familiarity with manga will be assumed.

“The one thing about this exhibition that I can absolutely promise is that you will become fluent in manga. By seeing this exhibition, you will have gained a new skill,” says the curator.

The first of the exhibition’s six sections, “The art of manga,” aims to give newbies the basic tools to understand the artform. Manga artist Kōno Fumiyo has created a visual grammar based on a twelfth-century handscroll and her animal characters will teach visitors how to read manga.

Thanks to the foyer area’s Alice in Wonderland theme, exhibition-goers will be gently introduced to the medium even before they enter. Not only are Alice’s adventures, in the form of Lewis Caroll’s text and John Tenniel’s illustrations, an early and famous example of pictorial story-telling, they have also greatly influenced manga, anime, and gaming in Japan. Lewis Carroll’s work has been translated into Japanese hundreds of times, including by the novelist Mishima Yukio. More recently, the story was illustrated by artist Kusama Yayoi.

Alice. (© Hoshino Yukinobu/Shōgakukan)

Alice. (© Hoshino Yukinobu/Shōgakukan)

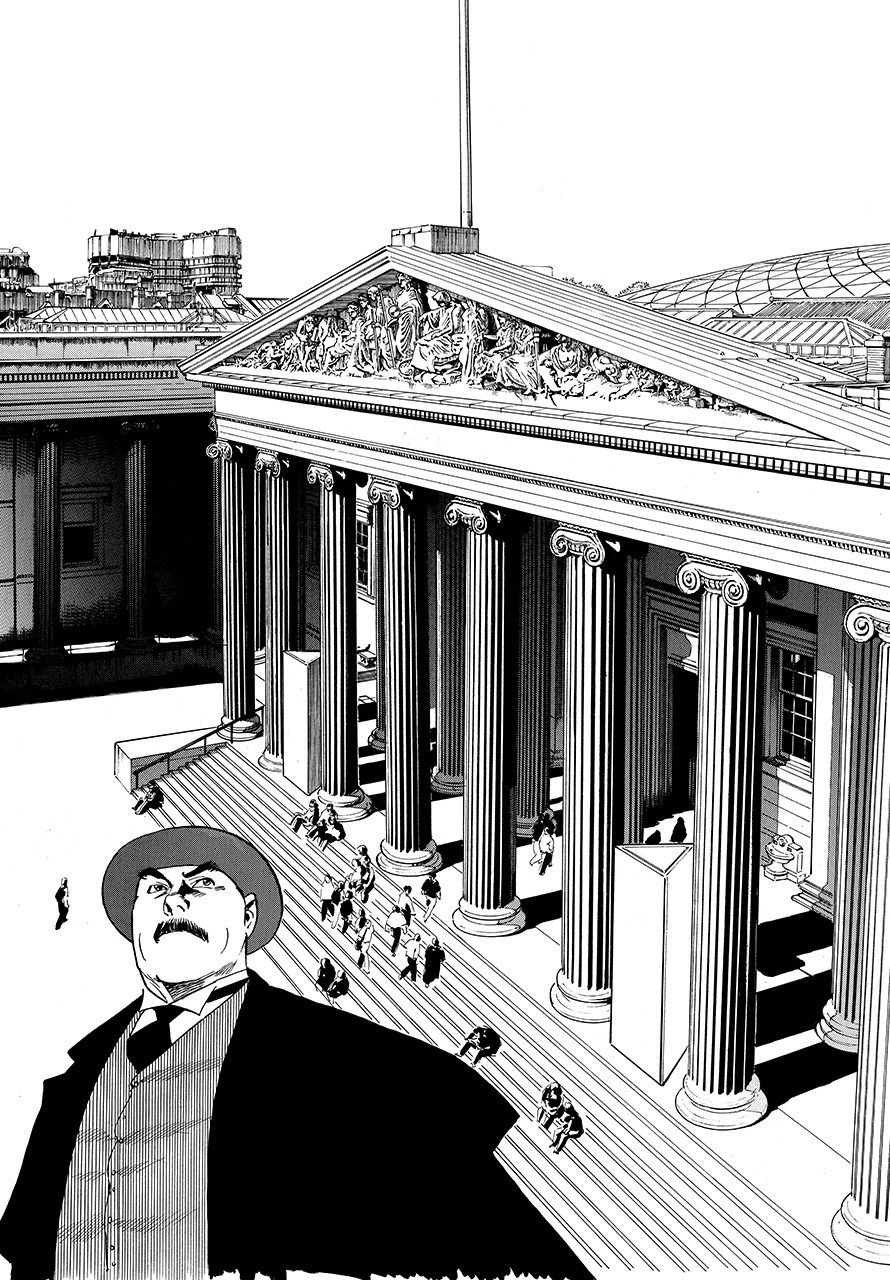

The second “Drawing on the past” section covers visual storytelling, manga’s history, and its present reality. This section includes a “digital experience” based on Hoshino Yukinobu’s Professor Munakata’s British Museum Adventure, a 2009 manga written in collaboration with the museum. At the end of the section visitors can enter Comic Takaoka, a re-creation of one of the oldest continuing bookstores in Tokyo.

Professor Munakata’s British Museum Adventure. (© Hoshino Yukinobu/Shōgakukan)

The third section, “A manga for everyone,” exhorts visitors to find their own favorite title. They can choose from the genres of sports, adventure, science fiction, transformation, love, eros, belief, spirit worlds, and horror.

“Power of manga,” the fourth section, looks at manga and society, with a special emphasis on manga fans, Comiket events (manga conventions), and cosplay (costume-wearing performance art).

The fifth “Power of line” section showcases the work of manga artists old and new. As well as original drawings from contemporary artists, this part of the exhibition includes the Shintomiza Kabuki Theater Curtain, painted in 1880 by the painter Kawanabe Kyōsai. The curtain is 17 meters long and features yōkai demons and ghosts that seem to jump out of the curtain and follow the visitor.

The Shintomiza Kabuki Theater Curtain is best viewed in person to experience its full scale. (© Tsubouchi Memorial Theater Museum, Waseda University)

Lastly, the sixth section, “Manga: no limits,” addresses manga’s expanding boundaries through exhibits on avant-garde expression, crossovers with other media such as gaming, and an exploration of manga’s ever deeper international influence.

Busting Preconceptions

In countries like Britain, which lacks a pictorial storytelling culture of the scale and tradition of manga, people might assume comics are trivial.

“Most people will think of manga as comics and for children, or little cartoons that you see on television; but really, manga is a deeper form of visual storytelling,” says Rousmaniere. “Manga is a way of telling stories for people who feel they don’t have history, or whose history is not recorded.”

The exhibition will feature manga inspired by the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disasters of March 2011. These include Ichi-F by Kazuto Tatsuta, based on the artist’s experiences working at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant after its meltdown. The work of Shiriagari Kotobuki, who started drawing manga about the disasters the day after the earthquake and has visited the disaster-hit areas numerous times, is also featured.

Another hard-hitting manga is Nōjō Jun’ichi’s account of the life of Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito). Interviewed as part of the exhibition, Nōjō reveals that he was influenced by the film The Queen, starring Helen Mirren. Rousmaniere notes that the subject would perhaps be too controversial for TV or film in Japan, at least if approached in the same way.

“Manga can show things that you can’t do in other ways,” she says, adding that visual images can sometimes be “more powerful” than the written word.

Rousmaniere also recalls how UK fans have told her they enjoy manga because of issues with their sexual identity.

“Somehow through manga they were allowed to identify and reinvent themselves. It had a seminal effect on their growth and mental well-being.

“You can take it lightly, but there is really deep meaning to this exhibition,” she says.

Cross-Fertilization and Change

Although it is often considered as quintessentially Japanese as sushi, the history of manga is indubitably one of cross-fertilization with Western comics. Famously, the artist Tezuka Osamu—often called the “god” of Japanese manga—adopted Disney’s big-eyed drawing style. Later, Disney returned the favor by borrowing Tezuka’s Kimba the White Lion for its Lion King.

Rousmaniere notes how the French cartoonist Mœbius (Jean Giraud) had a great influence on Ōtomo Katsuhiro, Urasawa Naoki, and Miyazaki Hayao, among other Japanese manga artists. And today digital technology has made this back and forth easier than ever both. The exhibition itself includes a collaboration between Matsumoto Taiyō and the French artist Nicolas de Crécy.

“I think you are going to see a lot more interaction,” says Rousmaniere.

Meanwhile, digital technology is changing manga in other fundamental ways. Sales of printed manga are declining in Japan (although not abroad). As part of the exhibition, visitors can download manga for free to their phones or other devices.

“What you are seeing is much more digital. There is more of an interest in gaming, and media convergence,” says Rousmaniere. “Manga is reinventing itself . . . the future is mobile.”

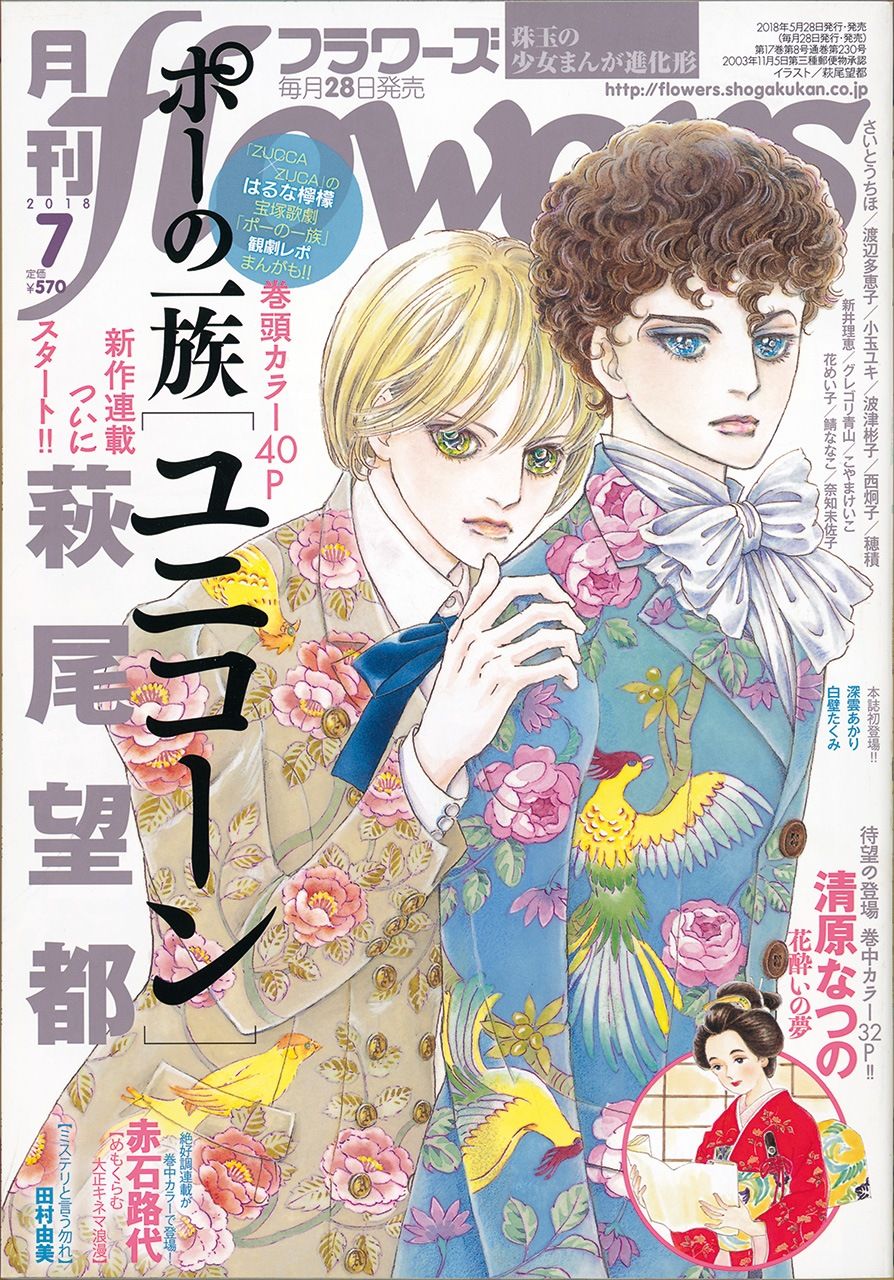

One of Hagio Moto’s representative works is The Poe Clan (Pō no ichizoku), published from 1972. The original drawing will be displayed at the exhibition. (© Shōgakukan)

New Ways of Seeing

As the exhibition’s curator, ultimately, what does Rousmaniere want visitors to get from it?

“In a nutshell, what I really care about is that they enjoy it and find out something about themselves, or something that they didn’t know,” she says. “I want them to come out with their manga.”

She also hopes that visitors will become more aware of the influence of manga around them on the street: in advertising, for example.

“They might not have recognized it before, but manga is already here,” she says. “I want them to come out and see their world a little bit differently.”

(Originally written in English by Tony McNicol with cooperation of the British Museum. Banner photo: The key visual for the exhibition comes from Golden Kamuy, which features the Ainu people in Hokkaidō. © Noda Satoru/Shūeisha.)