Wada Shizuka: A Voice for Older, Unmarried Women in Japan

People Society Lifestyle Work- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Hitting Rock Bottom

Wada Shizuka, a freelance music critic, was in her mid-fifties when she began to have serious doubts about Japan’s social and political systems. It was the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, and she was facing the worst economic crisis of her life.

But her financial troubles, as she recalls, began much earlier, around the time she turned 40.

“Before that, I managed to make a passable living as a writer. But after forty, the work quickly tapered off. I had no choice but to rely on part-time jobs to make ends meet. I worked in convenience stores, bakeries, supermarkets, restaurants, rice-ball stands . . . food-industry jobs for the most part.”

In every case, she was paid the minimum wage. When she started at a convenience store in 2008, at the age of 44, the pay was a mere ¥850 an hour—and it stayed like that for three years. Then, when she quit, the store advertised the opening at the rate of ¥900 an hour. “It made me so mad. Why couldn’t they have raised the hourly pay while I was working there?”

Even supplementing her journalism with part-time work, Wada was making a mere ¥1.5 million a year, which was barely enough to subsist on.

“I felt it was all my own fault,” she says. “I was constantly beating myself up over the path I’d chosen. Other women get married and have children. Marriage wasn’t very important to me, but I felt at least I should have gotten myself a permanent job. I really regretted that.”

When the pandemic hit in 2020, Wada lost the part-time job that had barely sustained her. At the age of 55, she had hit rock bottom.

Engaging with Politics

The COVID-19 recession had a disproportionate impact on the vulnerable in Japanese society, and women in particular. Businesses adjusted to the plunge in demand by laying off or terminating their nonregular workers. Almost twice as many women as men were affected.

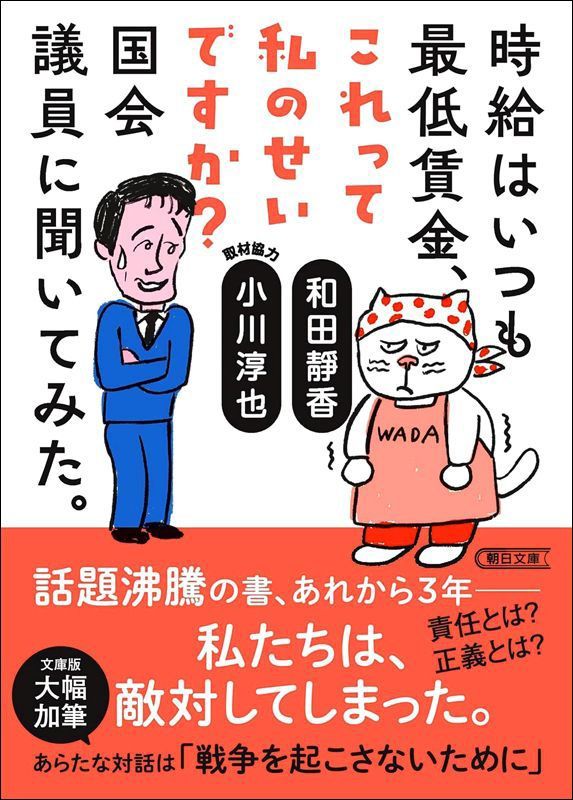

Wada’s 2021 book of dialogues with politician Ogawa Jun’ya was published in paperback (bunko) by Asahi Shimbun Publications in 2024.

Wada began to wonder how she would manage in old age. Was she solely to blame for this uncertain future that she faced? During that time of high anxiety and self-doubt, she happened to watch a Japanese documentary titled Naze kimi wa sōri daijin ni narenai no ka (Why You Can’t Be Prime Minister; released 2020) that followed the checkered career of Ogawa Jun’ya, a member of the House of Representatives (now secretary-general of the Constitutional Democratic Party) over a period of 17 years. Inspired by the politician’s efforts to reconcile his ideals with the realities of public service, she resolved to take her worries directly to him.

At a face-to-face meeting with Ogawa, Wada told him she wanted to work with him on a book that addressed her personal doubts and concerns from a political perspective. Won over by her determination and enthusiasm, he agreed to a series of dialogues. Wada pulled no punches, confronting Ogawa with her questions on a wide range of topics, from demographic aging and income inequality to taxes and social security. When she found his answers unconvincing, she would challenge him or dig deeper. These unscripted exchanges come across with great impact in her book, published in 2021 under the title Jikyū wa itsumo saitei chingin, korette watashi no sei desu ka? Kokkai giin ni kiite mita (Is It My Fault My Hourly Pay Is Always the Minimum Wage? I Asked a Diet Member).

Housing Crisis for Older Women

Reading these dialogues, one gains new insight into the factors that conspire to make life so difficult and uncertain for middle-aged and older unmarried women in Japan.

One of those factors is the availability of affordable housing. Although the Japanese government encourages home ownership through tax breaks and other means, Wada learned the hard way that it has little interest in guaranteeing housing as part of the social safety net.

“When I was in my forties, I found I could no longer afford the apartment I’d been renting, so I started working part-time at a convenience store to supplement my income. Two years later, I had to move anyway. From that point on, it was just one move after another, as I searched for a place I could afford. The real estate agent would size me up with a frown. ‘Freelance, is it? I’m afraid there’s not much for a single person your age.’ I began wondering how long it would be before no one would rent to me. That got me thinking maybe I should just hurry up and die. This is the situation facing an awful lot of solitary middle-aged and older women today.”

What about public housing?

“Public housing is considerably cheaper, but the vast majority of apartments are set aside for families—even though the number of single-member households is rising rapidly. There’s a very long waiting list for the few apartments available for singles. Tokyo Metropolitan Housing won’t even take my application, since its single occupancy units are reserved for people aged 60 and up.”

Japan’s Two-Tiered Pension System

Many women like Wada are products of the “employment ice age” that followed the collapse of Japan’s 1980s asset bubble. When corporations froze or drastically curtailed their hiring of regular employees in the 1990s and early 2000s, many new college graduates were obliged to accept nonregular employment (limited-term contracts) or go freelance. The freeze affected men as well as women, but the long-term impact hit women disproportionately.

“Many of the men who started out as nonregular workers back then were eventually able to transition to the status of regular employee,” says Wada. “But once a woman starts down that road, she’s apt to be stuck there for life.” The distinction between regular and nonregular employment has serious economic implications in Japan, especially after retirement.

“Japan has a two-tiered pension system,” Wada explains. “There’s the Employees’ Pension Insurance system for permanent corporate and government employees, and then there’s the National Pension system for everyone else. As a free-lancer or nonregular employee, even if you pay your monthly National Pension contribution [¥16,980 in 2024] faithfully for forty years, your post-retirement benefits still amount to only about ¥65,000 a month. Assuming it costs roughly ¥70,000 to rent a one-room apartment [in Tokyo], you’re in a hole that can only get deeper. The government needs to create more public housing so that older single people of limited means can live out their years in peace.”

Questioning the “Income Barrier”

Since last October’s general election, there has been much discussion about raising the annual income thresholds for paying income tax and social insurance premiums to encourage greater participation by women in the labor force. Under the current system, the wife of a permanent corporate or government employee is covered by the National Pension as a “category 3 insured person” providing she earns no more than ¥1.3 million annually. This means she can receive pension benefits when she reaches retirement age without paying anything into the system. However, once her annual income passes the ¥1.3 million threshold, contributions kick in, and her after-tax income can actually go down. To avoid this, many women deliberately limit the hours they work, restricting themselves to low-paying part-time jobs.

Wada feels the debate misses the mark.

“I get it,” she says. “People are struggling, so they prioritize their immediate after-tax income over the benefits they’ll receive twenty or thirty years later. But think about it. The whole system of exempting ‘category 3’ people from paying pension contributions is designed to maintain a gender-based division of labor, forcing women to settle for low-paying part-time jobs that supplement their husbands’ income. Women who aren’t dependent spouses don’t benefit from the system, and they tend to resent the homemakers who take advantage of it. So, the system also creates divisions among women.” Wada feels that taxes and social insurance contributions should be geared to each individual’s income level, regardless of their gender.

To her mind, the inadequacy of the National Pension is a far more serious issue. “Instead of haggling over the ‘income barrier,’ we should be talking seriously about raising the National Pension,” she argues. “There’s an urgent need to sit down and carefully restructure the social security system, but our politicians don’t want to open that can of worms. That’s the biggest problem.”

A Late Awakening

Wada came belatedly to a consciousness of gender discrimination in Japan; it was only in her fifties that she began to rage against it. “When I was young,” she admits, “I unconsciously accepted discrimination against women and even contributed to it in a way.”

In 1985, the year Japan enacted the Equal Employment Opportunity Act, Wada got a job as assistant to the music critic Yukawa Reiko. Viewed as a role model for women juggling work and family, Yukawa was deluged with requests for interviews and media features. Seeing how heavily Yukawa relied on nannies, housekeepers, and babysitters, Wada was irritated by the “superwoman” aura surrounding her boss.

“I thought, what’s so great about working if it means neglecting your family? Now I realize how tough it was for Yukawa back then, when she couldn’t count on her husband for any help at all.”

At the age of 27, Wada went independent as a freelance music critic. At first, she was delighted just to be making a living writing about the subject she loved. But the music industry’s gender bias affected her more and more as time went by.

“Women like Yukawa and Hoshika Rumiko, the first Japanese journalist to interview the Beatles, played a huge role promoting Western rock and pop music in Japan, and their contribution hasn’t been sufficiently acknowledged. Women writers in general are dismissed as lightweights capitalizing on passing fads.” There is good reason to believe that women are paid less per word for the same type of writing, and their work tends to dry up as they get older. Decades after the enactment of the Equal Employment Opportunity Law, the goal of equal pay for equal work is still a distant dream.

Seeking Political Parity

Wada is no longer looking to male politicians to address these inequities. “I’ve come to see that just being a woman means you’re at a disadvantage,” she says. “And the privileged inevitably see the world differently from the disadvantaged.”

Today, women account for only 19% of the lawmakers in the National Diet. Wada believes that it is vital to boost that percentage to guarantee unmarried women a minimum level of economic security in old age through such measures as reform of the social security system, an increase in the minimum wage (¥1,055 per hour on average as of October 2024), and policies to assist older women with employment and housing. But where to begin?

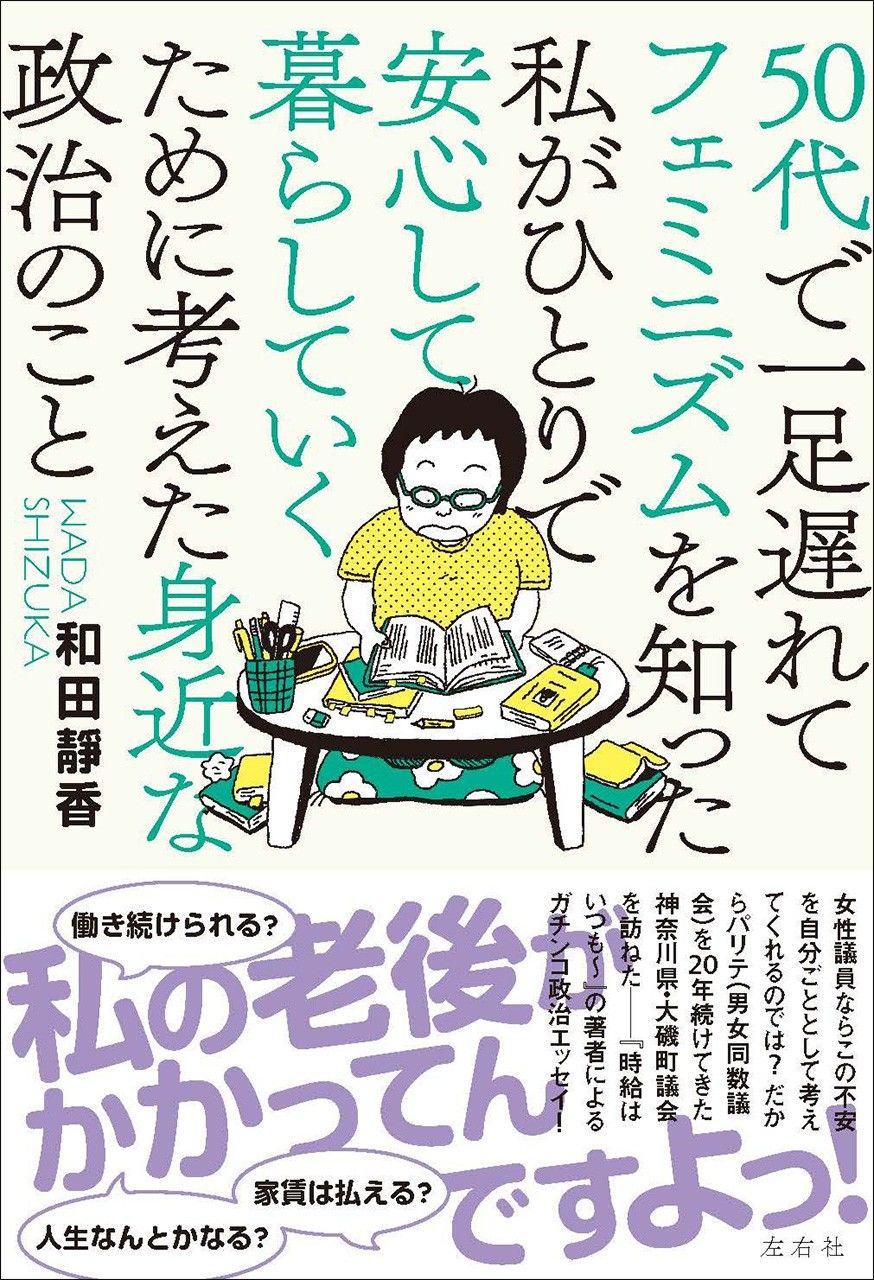

Wada decided to look into the Ōiso Town Council in Kanagawa Prefecture, the first local assembly in Japan to achieve gender parity. Her interviews with a broad range of women on the council—which still boasts parity between male and female members—taught her the importance of using local movements geared to citizens’ and consumers’ rights to build a sense of community and shared purpose. The lessons she learned are the subject of her second book: 50-dai de hitoashi okurete feminizumu o shitta watashi ga hitori de anshin shite kurashite iku tame ni kangaeta mijika na seiji no koto (Thoughts on Grassroots Politics for a Secure Future from Someone Who Came to Feminism a Bit Late), published in 2023.

Healing the Divisions

Wada is currently writing a series of articles profiling solitary middle-aged and older women for a major monthly magazine.

She introduces us to a woman so exhausted from juggling work and care of her aged mother that she was obliged to retire. Another of her subjects is a certified professional plagued by the insecurity of a nonregular government job. Then there is the 68-year-old music journalist, Wada’s senior colleague, who works night shifts to get by. Each one of them is giving it her all, making the best of the hand she was dealt.

Although Wada is doing better since her books came out, she does not feel her situation has changed fundamentally. “I’m still very uneasy about the future,” she says. “I may go back to working part-time. I still pick up the free classifieds at train stations and convenience stores to look at the help-wanted ads.”

At the same time, she has gained a new sense of purpose.

Wada realizes that politics is very much a man’s world, and that the path to parity will not be easy. For now, her focus is on using her skills as a writer to bring women together. “I write my articles with the intent of reaching out, finding other women with whom the content resonates, and forging new connections. Women are too easily pitted against one another, as we see with the issue of ‘category 3 insured persons.’ We’ll never overcome discrimination or elect more women to office unless we can unite and raise our voices as one. I want to start by helping to heal the divisions.”

(Originally written by Kimie Itakura of Nippon.com and published in Japanese on January 20, 2025.)