An Olympic Life: Hashimoto Seiko on Gender Equality in Japan and Realizing the Tokyo Games

People Society Politics Sports Tokyo 2020- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

On February 18, 2021, following the resignation of former Prime Minister Mori Yoshirō as president of the Tokyo 2020 Organizing Committee in the wake of his sexist comments regarding the role of women in athletic organizations, Hashimoto Seiko was tapped to replace him as head of the body in charge of preparing the postponed games, now slated to take place this summer. The text below is based on our December 2020 interview with the Olympian and politician.—Ed.

Trailblazer in Sports and Politics

An Olympian and politician, Hashimoto Seiko has been a pioneering force in Japanese society for the better part of four decades. She rewrote the record books as a two-sport athlete, appearing in seven consecutive Olympics—three summer and four winter games, for the highest total ever by a Japanese woman athlete—and earning a bronze medal in speed skating at Albertville in 1992. In the political arena as well, her unwavering drive and grit in challenging norms serve her as a member of the upper house of the Diet and as one of only two female ministers in Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide’s cabinet.

Forging new ground in Japan’s male-dominated society is a daunting venture, and Hashimoto has repeatedly drawn harsh rebuke from various quarters for her decisions. As a newly elected member of the House of Councillors, a seat she first won in 1995, she continued her athletic career and earned a berth in cycling to the Atlanta games the following year, prompting critics to openly question her ability to balance the two commitments. Hashimoto admits that the relentless scrutiny—including insinuations that the competitive cycling scene in Japan could hardly be too challenging if she could earn an Olympic slot without dedicating herself to training—took a toll on her mental wellbeing, but true to form, she refused to bow to pressure, closing the curtain on her stellar career only after appearing in the 1996 Games, her seventh Olympics.

Devoting herself to government, she continued to make headlines by breaking with convention. In 1998, her decision to marry her partner, a house guard at the Diet with three children, caused a stir among her colleagues. Two years later, at the age of 36, she became the focus of attention again when she gave birth to a daughter named Seika, meaning the Olympic flame. Hashimoto recalls the effects these two events had in Nagatachō, the heart of national politics. “Considering that it was unconventional at the time for a sitting legislator to tie the knot, the fact that I followed this up by having a baby was positively unfathomable.” She notes that up to then the only other Diet birth was by lower house member Sonoda Tenkōkō in 1949, a half century earlier.

Predictably, detractors wasted little time in calling for Hashimoto to resign, arguing that caring for a young child would make it impossible for her to fulfill her legislative duties. Hashimoto, on the other hand, saw an opportunity to prove to the political establishment that she could be a good mother while continuing to serve her constituents. A week after giving birth, she was back on the job, staying with her infant daughter in the Diet members’ dormitory, looking after her at her office, and even taking her along on official trips.

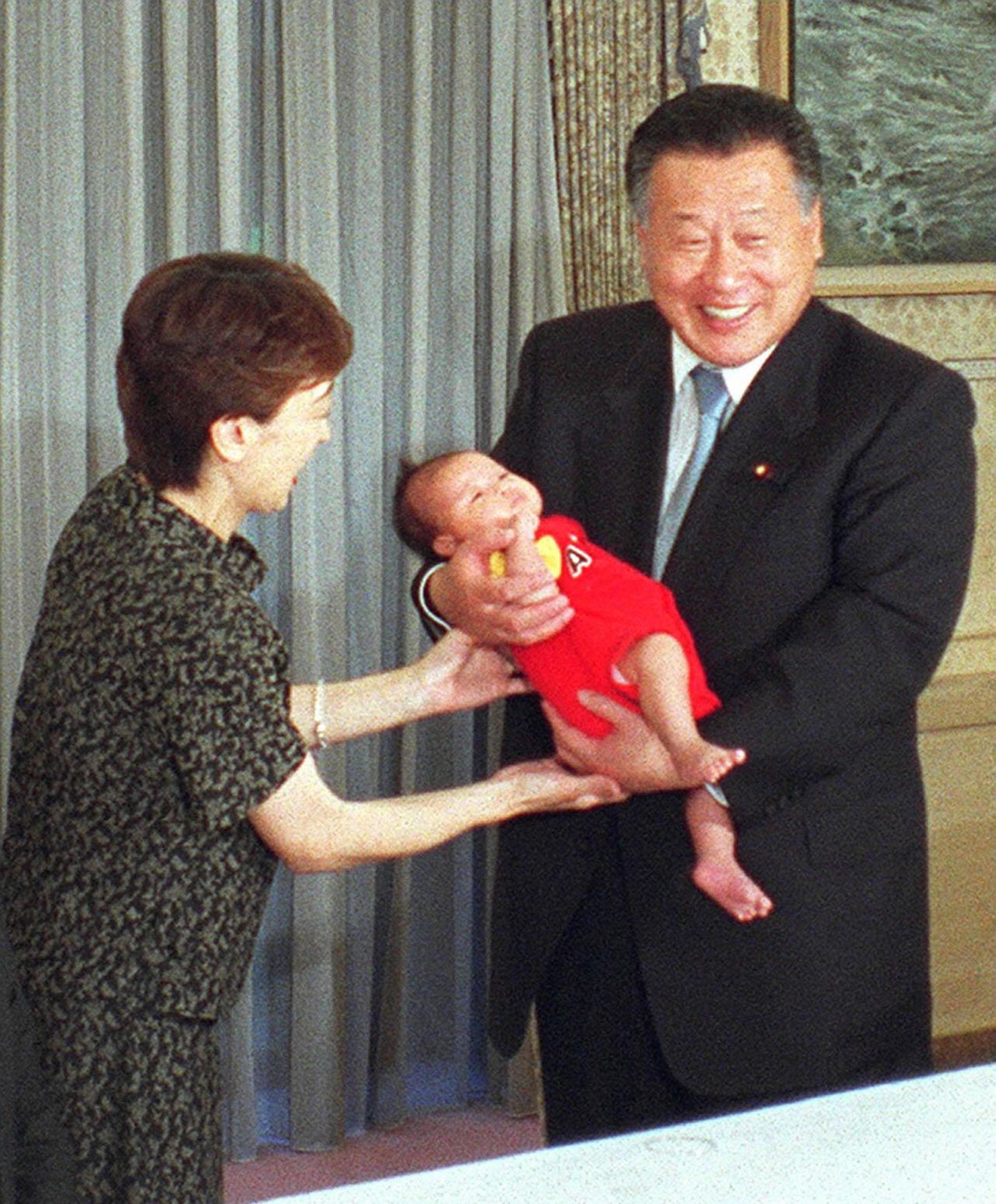

Prime Minister Mori Yoshirō holds Hashimoto’s one-month-old daughter Seika in June 2000. Hashimoto, who herself was named in honor of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, chose the name (meaning “Olympic flame”) in tribute to the Sydney Games held that year. (© Cabinet Office/ Jiji)

Hashimoto recounts how the birth of her daughter started the ball rolling on addressing the huge degree of gender imbalance in Japanese politics. “Up to then, giving birth was not even an officially recognized reason for missing a Diet session,” she notes. “Now that more female representatives are having babies, though, the atmosphere has changed, and male colleagues are less likely to react adversely when they do.”

Along with a daughter, Hashimoto gave birth to two sons, also giving them Olympic-flavored names: Girisha (“Greece”) and Torino (“Turin,” for the host of the 2006 Winter Games). Like other working mothers, she wished for a daycare center near her place of work. Together with fellow young LDP legislators Noda Seiko and Hase Hiroshi, she organized a nonpartisan group advocating for establishing a nursery facility near the Diet building. “If I had spearheaded these actions, I would have been accused of wanting it for selfish reasons, so Noda went to bat for the cause. Hase, meanwhile, helmed the group to make the point that daycare is not only a women’s issue,” she says. Hashimoto focused her attention on gathering information and building support. “We wanted the nursery not just for legislators, but for staffers and visitors coming to petition the Diet as well.”

The group’s efforts paid off in 2010, when the government established a daycare center inside a newly constructed complex housing politicians’ offices across the street from the Diet building. For the first time, anyone with business at the Diet, from politicians and staff to regular citizens taking tours or coming to petition the government, had access to nursery care, as did local residents, who can also use the center’s services. While the facility came too late for Hashimoto and other core members to use, they celebrated it as a victory for working parents in the country’s center of political power.

Boosting Female Representation

Japan lags far behind other G7 nations, and in fact much of the globe, in terms of female participation in society, ranking a dismal 121st out of 153 countries in the 2019 Global Gender Gap Report announced by the World Economic Forum. Progress in political empowerment has been particularly slow. As head of the Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office, Hashimoto was instrumental in establishing the goal under the Fifth Basic Plan for Gender Equality of increasing the ratio of female candidates in lower house elections from 17.8% logged in 2017 and 28.1% reached in upper house elections in 2019 to 35% overall by 2025. Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide approved the revised goals in December.

Hashimoto stresses that increasing female representation in government is crucial to improving the plight of women in Japan, which has become even more precarious in the pandemic. Citing how women have been disproportionately affected by the loss of jobs due to COVID-19, she argues that the only way Japan will succeed in addressing the needs of the historically underserved half of the nation’s electorate is by raising the number of female voices in the halls of government.

Achieving this, however, will require reshaping awareness in the political system, starting with Japan’s regions. “Boosting the number of female legislators on the national stage must be accompanied by increased participation at the local level,” she explains. “All parties need to work to suppose women candidates, and for this, we’ll need to see a change in consciousness at the prefectural party leadership level. These are the groups that make the early decisions in the process of candidate selection, after all. And we also need to create an environment that makes it easier for women who aspire to hold office to take part in local politics.”

One area that Hashimoto says needs to be addressed is the way campaigns are run. She notes that the huge burden involved in running for office prevents many capable women from throwing their hats into the political arena out of concern for their families. “We have to break free from hidebound ideas of what elections are supposed to be, thinking of ways for female candidates to deliver messages on their policy ideas directly to the people. With the lifting of the ban on Internet election campaigns, it’ll be important to come up with new, effective messaging approaches, while also preventing online harassment.” All jobs involve hard work and strenuous effort, she notes, but wasteful efforts are to be avoided. “We have to work on making the process more transparent as a whole so it’s easier to determine what areas politicians have to truly focus on and what drudgery they can cut out of the picture.”

Turmoil over Surnames

As part of its women’s empowerment strategy, the government readjusts the goals laid out in the Basic Plan for Gender Equality every five years. Recently, debate within the ruling LDP over the wording of the newest revision bogged down in a gaping divide within the party on the question of allowing married couples to use separate surnames, something Japan’s Civil Code forbids. Following heated discussion, party members settled on a lukewarm pledge to “carry out further consideration of the issue,” paying heed to the sense of family unity and the impact on children of any concrete proposal for married couples’ family names.

Hashimoto acknowledges that a deep-rooted belief among some LDP lawmakers in “traditional family values,” including insisting that a woman take her husband’s surname after marriage, has stifled debate. However, she hopes to assuage concerns by pointing out that the proposed system allowing separate names would not be mandatory, but give couples the right to choose what is best according to their situation. “We aren’t trying to force couples to use separate surnames,” she asserts. “I hope our party can keep these facts squarely in mind while we carry out the further needed debate in a calm manner.”

Japan is the only advanced nation to require married couples to have the same surname, a policy that disproportionately affects women. Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare data shows that 96% of married women take their spouse’s name. However, a recent joint survey by Waseda University and civic groups found that slightly more than 70% of respondents were in favor of couples having the right to use different surnames.

While Hashimoto says it is important to respect each person’s values, she contends that policies need to reflect social change. “Nuclear families are now the norm,” she explains. “As one-child households have increased, a growing number of young people who are thinking of getting married want to carry on their family name. I’d like those lawmakers who are wary of allowing dual surnames to carefully consider whether forcing married couples to have the same last name will necessarily safeguard family ties. I hope they acknowledge that the younger generation, on which Japan’s future rests, sees things differently. We must respect the wishes of young people to retain their family names and understand that their family connections will be different from those in the past.”

Olympic Aspirations

Born in September 1964, just five days before the start of the Tokyo Summer Olympics, Hashimoto says that as a girl her father Zenkichi would tell her that she was destined to compete in the games. Growing up on a ranch in Hokkaidō, during the long winter months she would skate on a pond on the grounds with her father’s words reverberating in her ears. However, she recalls that it was not until she was a first grader and watched the Sapporo Winter Olympics on the television that she began to get an inkling of what it meant to be an Olympian.

Health issues would plague her early life, though. In the third grade of elementary school she was diagnosed with a kidney disorder and was forbidden from participating in sports for two years while she underwent treatment. During one of her hospital stays, she met a girl who was the same age, and the two quickly became friends. While Hashimoto’s condition gradually improved, her new companion tragically lost her fight. Hashimoto recalls how before her friend passed away she asked her to live on for her as well—a request the minister says she still keeps in her heart.

Health problems would sidetrack Hashimoto several other times in her career. In the eleventh grade she won the All Japan Speed Skating Championship, but the following year her kidney condition flared up again. Her harsh training also took a toll. At one point she had to be hospitalized after suffering stress-induced respiratory failure, and while being treated she contracted hepatitis B. After recovering, she made her Olympic debut at the age of 19 at the 1984 winter games in Sarajevo.

Each new medical crisis added to the list of medications doctors wanted to prescribe for the young athlete, but she could not take these drugs and pass the regular doping tests in her sport. Working closely with the team doctors, though, she nursed herself back to health through a regime that included changing her diet and applying the principles of exercise physiology to her training. Her efforts paid off, and at the age of 27 she became the first Japanese woman to medal in speed skating, winning bronze in the 1,500 meters at the 1992 Albertville Winter Olympics.

Hashimoto shows off her Olympic speed skating bronze medal in Albertville, France, in February 1992. (© Jiji)

“Sports,” Hashimoto declares, “give us the opportunity to face life’s challenges head on and overcome them.” She does not believe this is limited to only athletes, but is an experience shared even by supporters. She points to the efforts of Paralympians in particular. “Para athletes are a testament to what can be achieved through sports. Their hard work brings courage in particular to the children who see them compete, teaching them that no challenge is unsurmountable.”

Committed to the Tokyo Games

As a seven-time Olympian and Olympic minister, Hashimoto feels a deep sense of purpose in overseeing preparations for the Tokyo games, which have been postponed until 2021 due to the coronavirus. She says the pandemic has brought immense challenges, but that she remains firmly dedicated to holding the Olympics and Paralympics. At the same time, she emphasizes that the global health crisis is an important opportunity for the sports world and society as a whole to reevaluate the meaning of the games.

“Los Angeles in 1984 was when the Olympics first started to become commercialized,” she explains. “Since then the games have grown progressively larger. I see Tokyo as a chance to return the focus to the founding principles of the modern Olympics, which are promoting world peace and bringing people from different countries and cultures together in friendship.”

Turning to the legacy of the Tokyo games, Hashimoto believes that advances in preventive medicine and care will have a lasting impact on the quality of people’s lives around the globe. “Athletes take full advantage of leading research in areas such as diet and the mechanisms of fatigue to remain in top form. However, this same knowledge can be applied in the medical care of ordinary citizens, helping people live longer and healthier lives. Spending less effort on treating symptoms and working more to prevent illness in the first place will ease the mounting burden on the healthcare systems while also creating new industries. I hope the Tokyo Games can stand as a model for governments in designing policies that promote the benefits of exercise, including in maintaining health and improving the physical fitness of children.”

The public remains skeptical about holding the Olympics amid a pandemic, though, and Hashimoto understands that success hinges on clearly demonstrating to people the significance of going ahead with the Tokyo Games. Although faced with innumerable challenges in the coming months, she is committed to succeeding. “At the end of the day, I am certain the Olympics will speak for themselves.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Interview and text by Itakura Kimie of Nippon.com. Interview photos by Ōkubo Keizō.)