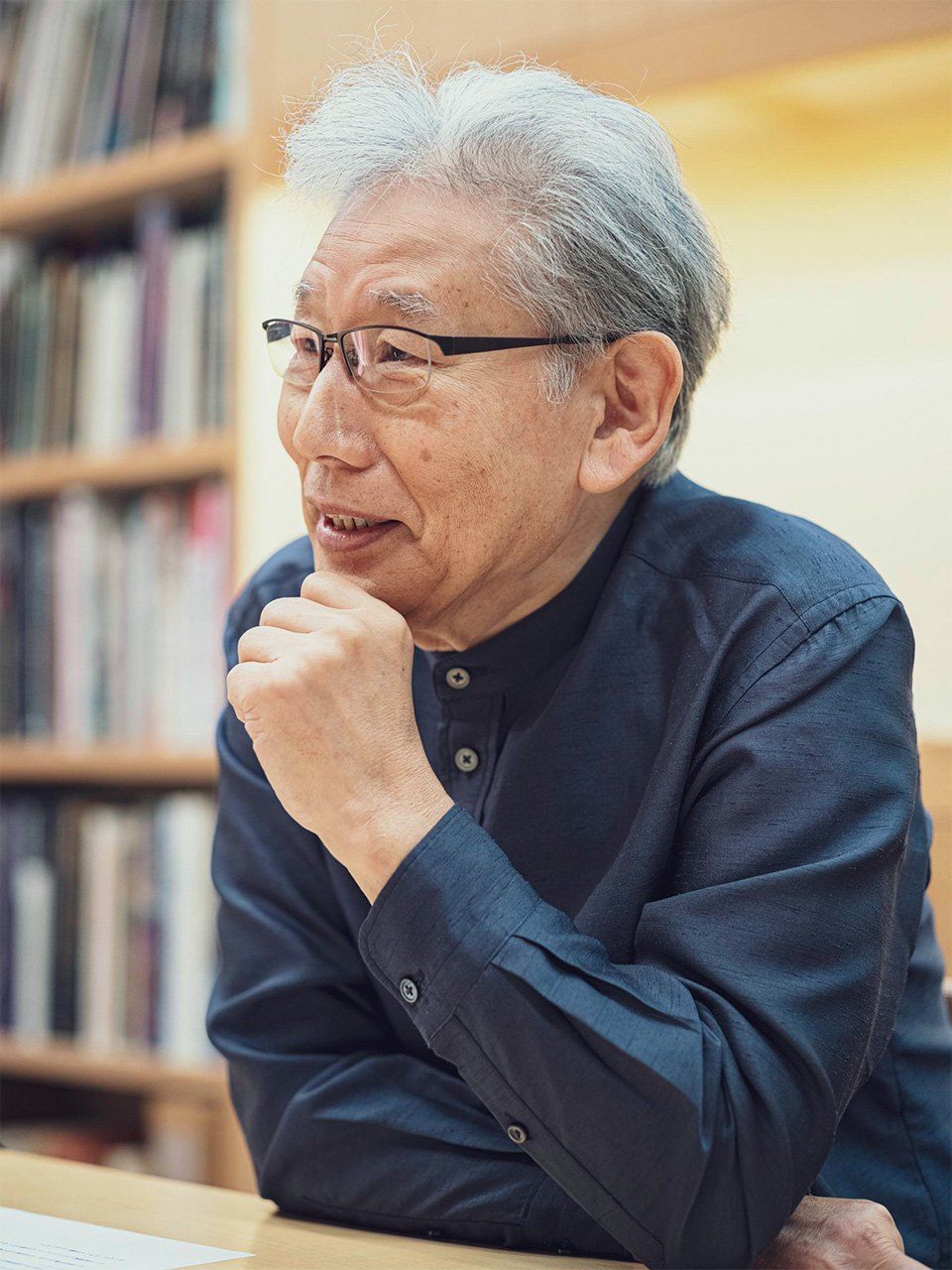

Murose Kazumi: The Light Fantastic of Lacquer

Culture Art Lifestyle- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Creating Lacquerware Makes Time Move Quickly

“Lacquer art might be called the decorative expression of light. The combination of the shining black lacquer and the lustrous gold is a perfect way to convey radiance.”

Lacquerware, produced by applying sap from the urushinoki, or Japanese lacquer tree, to vessels in order to decorate as well as protect them, has long been an important component throughout Japanese lifestyle and culture, used on all manner of objects from everyday soup bowls to works of art. The technique that Murose Kazumi uses to create his pieces is known as togidashi makie, in which, once gold powder has been sprinkled on the lacquer to form the design, it is coated by further layers of lacquer and then the surface burnished with charcoal to reveal the design underneath.

Gift from Heaven, a box for holding letters featuring makie lacquerwork and mother-of-pearl inlay, exhibited at the seventieth Japan Traditional Kōgei Exhibition (2023). (Courtesy the Japan Kōgei Association)

Gift from Heaven, completed in 2023, features a glossy mirror-like lacquer surface under which gold grains in various colors, shapes, and textures are overlapped three-dimensionally to create a rich decoration.

“I depicted grapes, ripened by the sun and hanging heavy on the vine, while squirrels play nearby. My idea was that it would convey the power of sunlight to nurture plants and animals, as well as how people are blessed by that power.”

Each piece takes an inordinate amount of time to create. The first step of the process is to apply linen cloth to a wooden base to reinforce it and then add a base layer of lacquer. This is left to dry and then polished. After this, further coats of liquid lacquer are repeatedly added and polished. This is then followed by the decoration process.

For Gift from Heaven, the leaf and sunlight designs were drawn using lacquer and then gold powder sprinkled on top by flicking it with the finger from a funzutsu, a bamboo tube that holds the powder. Another layer of lacquer was then applied on top and left to harden, after which the surface was burnished using charcoal to reveal the designs. The grapes and squirrels themselves were created using raden, a decorative mother-of-pearl inlay technique. This technique involved cutting mother-of-pearl shell into patterns, which were then pasted onto the lacquered surface and polished with charcoal to finish.

Funzutsu bamboo powder tube. (© Mori Masatoshi)

“A year quickly passes as I go through this process of applying the base coat to the wood and then repetitively polishing and recoating. For a piece the size of Gift from Heaven [roughly A4 size and just over 10 centimeters tall], around a year was needed for the decoration process too, so counting in the planning time, each of my pieces can take three to four years to complete. Over time, lacquer hardens, becoming stronger and more transparent, so if well preserved, its beauty can last for a good five hundred years. This longer time cycle for working with lacquer makes it feel as if you are on a different timeline to usual.”

Raden mother-of-pearl inlay. (© Mori Masatoshi)

A Father’s Teaching: Creativity through Actions not Words

Murose’s father was the lacquer artist Murose Shunji. Part of their house was his father’s studio where the young Murose would play.

“When I was seven or eight, I said I wanted a plastic model of a motorboat, so my father made me a boat by pasting thick pieces of cardboard together in layers and then applying cashew oil instead of urushi. It was a Japanese-style ship, so looked nothing like a motorboat, but I was forever playing with it, floating it in the bath, and it was after that I became interested in the craft. When I think back now, I guess rather than using words, he was teaching me through actions how to make things with my hands.”

Among the master lacquer artists who would often come to visit Shunji were Rokkaku Daijō (who later became a professor of Urushi Art (Japanese lacquer) at the Tokyo University of the Arts) and Masumura Mashiki (designated a living national treasure for the kyūshitsu Japanese lacquering technique in 1978). Murose found himself being drawn more and more toward lacquer art and, of his own accord at the age of fourteen, he started helping Shunji with his work and learned about the joy of creating.

“I grew up watching my father work and I loved making things, so I had always wanted to become a lacquer artisan. But at that time, you couldn’t make a living from it. I talked to my father, but all he said was ‘you can’t support yourself as a lacquer artist.’ My teachers at high school were very against it too, saying ‘those old traditions are going to disappear.’ So, I took the attitude that ‘if that’s the case, I’m going to watch it disappear.’”

On enrolling at the Tokyo University of the Arts, he visited Shunji’s teacher Matsuda Gonroku (designated as a living national treasure of makie in the field of lacquer art in 1955) to let him know he would be studying there.

“Even now, I remember how nervous I was at the time. He spent half the day passionately explaining lacquer to me, someone young enough to be his grandchild. Since then, Matsuda-sensei has been the person to whom I aspire.”

Matsuda did not instruct him though “how to make things.” Instead, he talked about the creative mindset, in other words, “the philosophy of making things.”

“One of Matsuda-sensei’s teachings was ’learn from people, from things, and from nature.’ ‘People’ refers to predecessors, such as masters and senior artisans; ‘things’ are past works and techniques that senior artisans have handed down; and ‘nature’ is lacquer, along with animals, plants, and the energy of nature, with the lesson being that I needed to study from each of those. I have kept that teaching close to heart while pursuing expression in lacquer art.”

When it came to making lacquerware or rather the techniques, he learned the basics from his father Shunji and then went on to study more diverse ways of makie expression from his graduate school professor, Taguchi Yoshikuni (designated a living national treasure for makie in 1989).

“I believe techniques are not something to be taught, but learned by heart through the experience of making mistakes over and over as you create. Mistakes are actually an asset.”

Tradition is the Accretion of Innovations

Despite striving to create every day, it was still not easy to make a living as a lacquer artist.

“People only really began purchasing my work from when I was around fifty. Up to that point, as I couldn’t support myself just through my art, I worked during the day repairing cultural assets and teaching lacquer art, while continuing to work on my own pieces at night. I still thought it was best to do what I loved.”

Murose learned a lot from his work on preserving cultural assets. He led a team of eighteen researchers and technicians on the restoration and reproduction of the national treasure Ume makie tebako, a plum-blossom design cosmetic box dating from the Kamakura period (1185–1333).

“I’d previously assumed that the gold background in makie should have an even gold finish, but I discovered through restoring the Ume makie tebako that the technique in the Kamakura period was to make use of the gold grain textures. This freed up my thinking, letting me understand that any expression was possible.”

The restoration took three years and was completed in 1998. He was forty-eight by then. This revelation prompted him to begin experimenting with three-dimensional expression by shaving lumps of gold to intentionally create powder particles that differed in shape and coarseness.

His efforts to produce a new style resulted in Colored Lights, an octagonal box with makie lacquerwork and mother-of-pearl inlay, which won the Governor of Tokyo’s Award at the Japan Traditional Kōgei Exhibition in 2000, when he was fifty.

Colored Lights, an octagonal box with makie lacquerwork and raden mother-of-pearl inlay, exhibited at the forty-seventh Japan Traditional Kōgei Exhibition (2000). (Courtesy the Japan Kōgei Association)

“The culture of makie has existed for more 1,200 years and in all that time black and gold have been the two main colors. Based on that tradition, for Colored Lights, I added color by using mother-of-pearl inlay and dried lacquer powder, as well as further applying layers of gold powder in differing particle sizes to give a greater sense of depth.

“It is often thought that traditional crafts mean the preservation of ancient techniques and aesthetics. However, while the basic techniques remain the same, the materials and styles of expression change. Basically, I think that tradition is the accretion of innovations and that’s why this work has significant meaning for me because it’s given rise to a completely new form of expression.”

Murose was designated a living national treasure for makie in 2008. According to an Agency for Cultural Affairs’ press release, he was recognized for “creating works that are based on traditional techniques, while adding his own originality and incorporating a wide variety of colorful expressions. His works feature neatly executed designs and compositions that convey modern sensitivity with elegance and style.”

Art Enriches Both Spirit and Society

Murose also puts a lot of energy into spreading the culture of lacquer art. In 2007, he participated in an exhibition at the British Museum, as well as giving a lecture and demonstration, which led him to start promoting lacquer culture from his base in London. He has been engaged at the Victoria and Albert Museum for more than 20 years, researching lacquerware and teaching repair techniques.

He also creates opportunities for children to come into contact with lacquer by holding workshops for children in Japan. This activity started after the Great East Japan Earthquake and has been running from 2012 through to the present.

“There’s a limit to what I can do as an individual. But if the splendor of lacquer and craftwork can be widely communicated, lacquer culture will continue even after I have gone. That is why I feel conveying Japanese culture is an important part of my work.”

Murose works hard every day both creating lacquer art and passing along its culture. What is the source of that passion?

“I may not have come this far if not for lacquer. It is truly amazing. To begin with, I’d like people to actually touch real lacquerware. It feels lovely, moist yet silky, and that alone has a calming effect. Art is something that enriches the spirit. I believe that if this can be conveyed to as many people as possible, all of society can be enriched.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Interview and text by Sugihara Yuka and Power News. Photos by Mori Masatoshi unless otherwise noted.)