Tsuchiya Yoshinori: Nature’s Pure Colors

Culture History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Constantly Honing Sensitivity

“I love the beautiful items that adorn people and have constantly pursued this art.”

Standing in front of Tsuchiya’s works gives rise to an unusual sensation. It is as if a vague childlike image of beauty has become embodied in each piece. The fabric, with its dreamlike colors, almost feels like it could have been created by Orihime, the gifted weaver in the folktale of the Tanabata star festival.

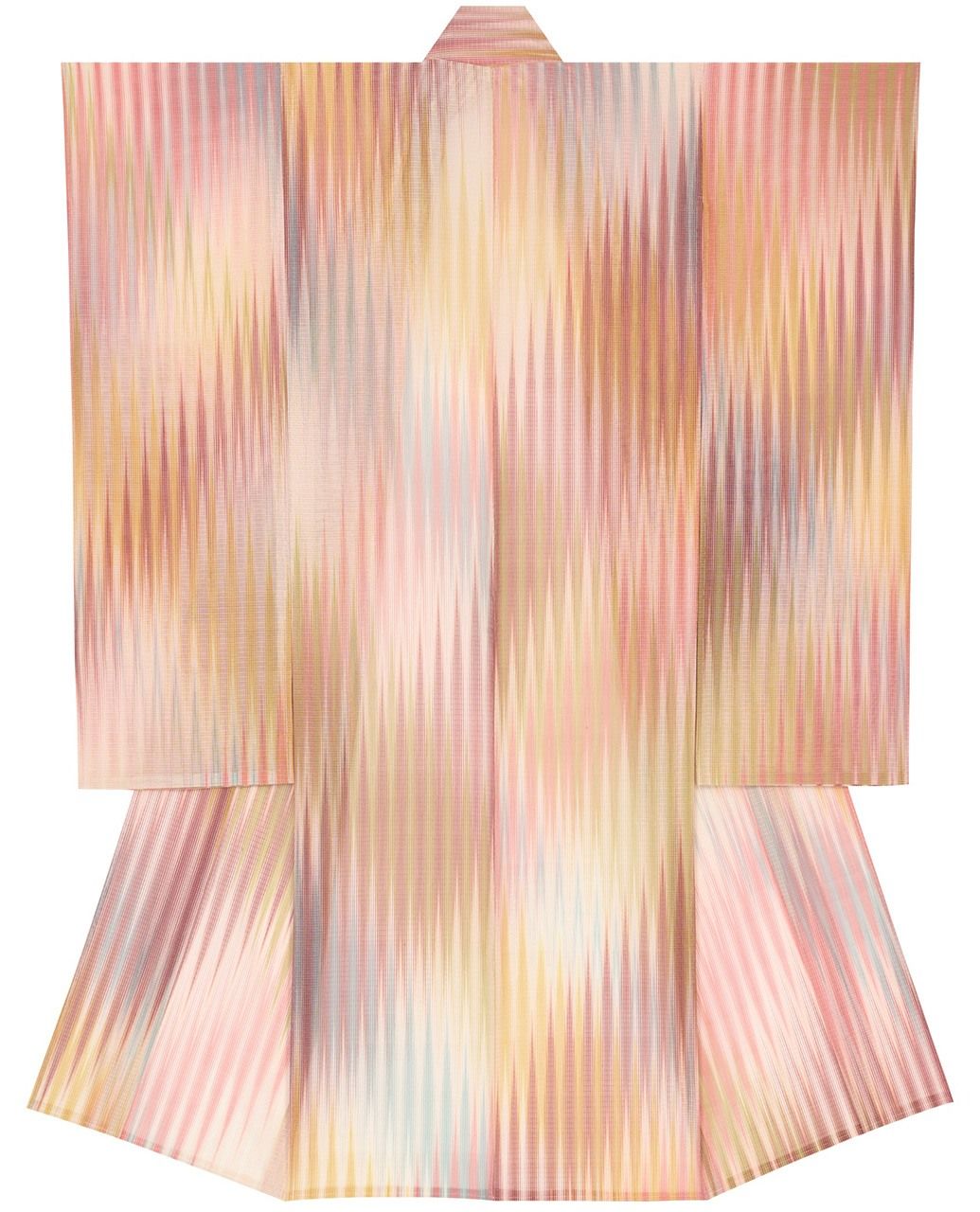

This work is titled The Peony Pavilion. It was presented at exhibition in 2023, having taken around six months to complete. The title of the piece comes from a traditional Chinese play of the same name that at one time was performed by the kabuki actor Bandō Tamasaburō V (recognized as a living national treasure in 2012 for onnagata female roles), of whom Tsuchiya has been a long-time fan.

The Peony Pavilion, a monsha furisode long-sleeved kimono, exhibited at the seventieth Japan Traditional Kōgei Exhibition (2023). (Courtesy the Japan Kōgei Association)

“The motifs are not necessarily inspired by anything specific. I think it’s important to see and experience a variety of things to constantly hone one’s sensibilities.”

The Peony Pavilion was created using monsha, or figured silk gauze, used by the nobility for summer garments during the Heian period (794–1185). Monsha is a type of mojiri-ori weaving, (literally “movement weave”), in which adjacent tateito twisted warp threads are woven together, which Tsuchiya uses to create an ishidatami checkerboard pattern by combining a sha light, transparent plain gauze weave with a hira-ori denser linen weave.

A weaving loom. (© Baba Keisuke)

What further sets apart Tsuchiya’s work is his use of kasuri, a type of ikat dyeing. The warp threads are partially dyed and when they are woven together, it results in a unique pattern known as kasuri. He uses an original method, dyeing the kasuri threads in five stages, to create gradations.

“Anyone can use the technique that creates blurred edges in the kasuri pattern. This, however, came about from the simple idea that even if it is disarranged, the pattern will still look beautiful if the threads are gradated in color. The scenery around the Nagara River in my hometown looks hazy, especially in summer when there is a lot of water vapor forming a mist in the air. It may be that delicate natural scenery influenced this technique.”

The Nagara River. (© Kawagoe Yūsuke)

Before threading the loom, a zurashi shifting device is used to misalign the gradation-dyed threads, creating a much deeper and refined kasuri pattern.

Plant Colors Led to Dyeing and Weaving

Tsuchiya uses natural plant dyes to dye the threads himself, seeking out different colors. In his work, The Peony Pavilion, the red of the peony was created using Indian madder, the yellow was from the buds of the Japanese pagoda tree, a deciduous shrub belonging to the legume family, and the blue from the berries of the kusagi harlequin glorybower, a flowering plant in the mint family. Meanwhile, the yellow in his piece Unasaka (border between the worlds of humans and the sea god) was created using Indian indigo.

Unasaka monsha kimono, exhibited at the sixty-fourth Japan Traditional Kōgei Exhibition (2017). (© Kawagoe Yūsuke)

“Vegetable dyes have very beautiful, transparent colors that can be used to create tones that range right from the understated to the very vivid. Encountering these colors set me on the path into dyeing and weaving.”

In his twenties, while at art college in Kyoto, Tsuchiya became interested in vegetable dyes and so participated in a studio visit. It was there he met Shimura Fukumi (designated as a living national treasure for tsumugi-ori weaving in 1990.)

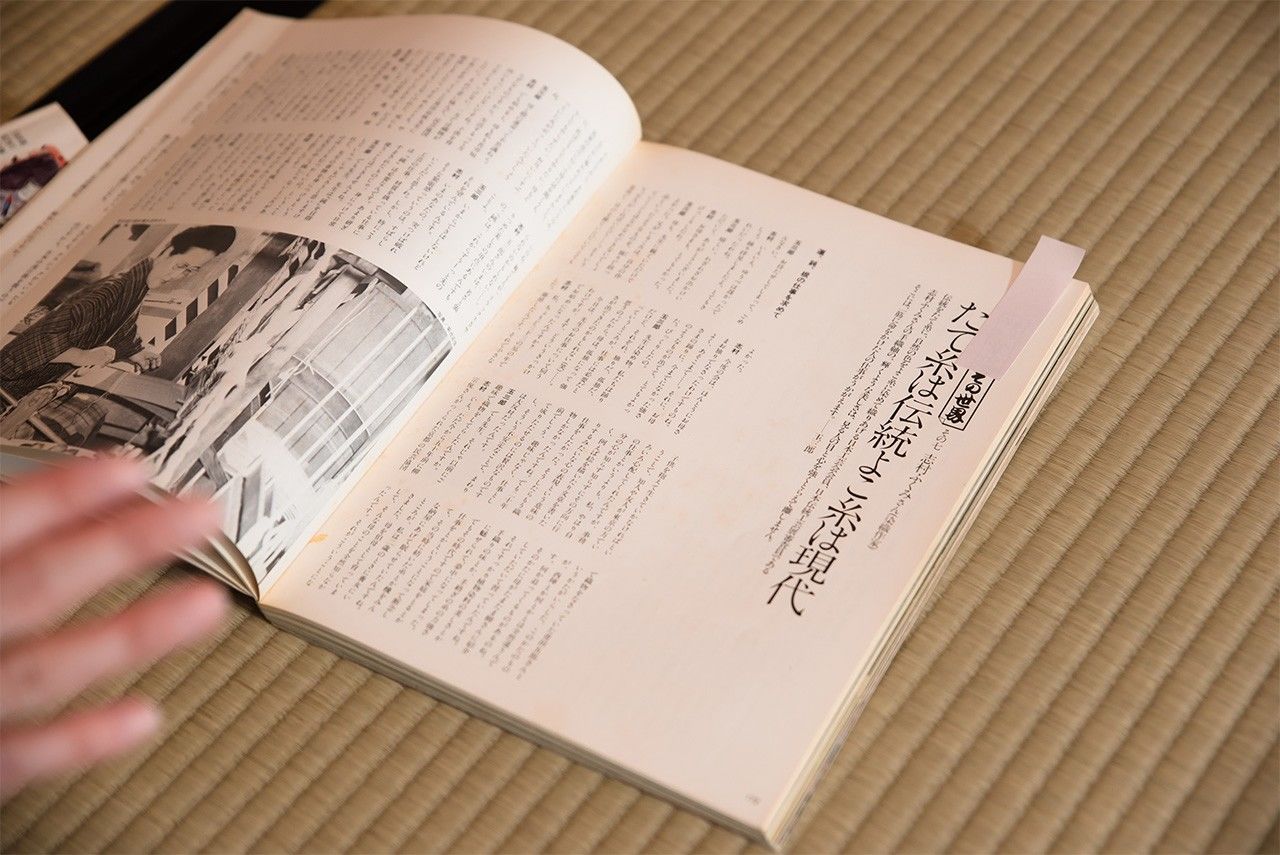

After that, he happened to come across a conversation between Shimura and Bandō Tamasaburō V, in a Tamasaburō photo collection and further still found a poem by Shimura in a magazine featuring one of his favorite artists Jean Cocteau.

Tamasaburō’s photo collection, including a conversation between Shimura and himself. (© Baba Keisuke)

“I was deeply moved when I read Shimura’s poem in that magazine. It spoke of what if we could see textiles with more sensitivity, and it made me admire her, as I could sense she was a wonderful teacher.”

A short while later, on seeing Shimura’s exhibition, he decided to pursue dyeing and weaving.

“I was strongly attracted to the beautiful colors and bold style of her work, and she let me join her studio. I feel like something drew me down the path of dyeing and weaving.”

As the only male apprentice under Shimura, based in Kyoto, he learnt the basic techniques of dyeing, weaving, and temporary tacking. He was also instructed on the philosophy of artisanship, and Shimura’s thinking that the colors nature provides need to be valued particularly influenced his creative work after that.

Threads dyed by Tsuchiya. (© Kawagoe Yūsuke)

Combining Traditional Techniques

On completing three and a half years of training in Kyoto, Tsuchiya returned to his hometown of Seki, Gifu Prefecture, and became independent.

“I returned to Gifu for financial reasons. It was difficult making a living as an artist and it was only much later that I felt I could follow this path.”

In his thirties, he created works using the tsumugi-ori weaving technique learned at Shimura’s studio, and then from around forty, he began making pieces using suzushi raw silk pongee, a thin, transparent fabric made from unprocessed, unrefined silk yarn, woven using a simple hira-ori linen weave technique.

“My love of transparent things led to me weaving with raw silk. When I was a child, I thought the koto teacher, a former geisha, who lived in the neighborhood, looked elegant in her kimono.”

Ever since learning the basics of the kasuri technique under Shimura, he has been honing his skills. In 1996, his work Ayu-no-se (Sweetfish Rapids), combining kasuri and suzushi techniques, was praised for its technical excellence and originality, and resulted in it receiving the Japan Kōgei Association’s President’s Award. He was 42 at the time.

Ayu-no-se suzushi raw silk kimono, which received the President’s Award at the forty-third Japan Traditional Kōgei Exhibition (1996). (Courtesy the Japan Kōgei Association)

“In my thirties, I created works freely without fear and it felt like I could do anything I wanted. But of course, that alone does not make you the “real thing.” I started thinking that I needed to study somewhere, so just before I turned forty, I began submitting my work and being involved with the Japan Kōgei Association, under which many artists are engaged in preserving and promoting traditional crafts.” –

For two years after receiving the President’s Award in 1996, he participated in technical training sessions held for members of the association and studied under Kitamura Takeshi (1935–2022), who was designated a living national treasure for ra (a complex gauze weave) in 1995 and for tatenishiki (a warp-faced compound weave) in 2000.

“I was taught more than ten different weaving techniques, but the one I wanted to master the most was monsha, so I studied that one extra hard. It was during that time that my techniques for kasuri and monsha naturally overlapped.”

This combination of the two techniques led to a unique style that was highly praised and in 2006 his work Gekkakeiin (Babbling Mountain Stream in Moonlight) was exhibited at the fifty-third Japan Traditional Kōgei Exhibition, winning him the Minister of Education Award. In 2010, he was designated a living national treasure for monsha.

Gekkakeiin, a monsha kimono, exhibited at the fifty-third Japan Traditional Kōgei Exhibition (2006). (Courtesy the Japan Kōgei Association)

A 2010 Agency for Cultural Affairs’ press release evaluating Tsuchiya stated that “through adding kasuri to monsha to create textiles that harmoniously combine two traditional techniques, he has established his own style, forming a uniquely exquisite and clear worldview”.

Tsuchiya at work. (© Kawagoe Yūsuke)

Led and motivated by what he loves—kabuki, art, geishas’ way of dressing, the colors formed from nature, and monsha—Tsuchiya’s expressions have an infinite purity and freeness to them.

Recently, his interest has been drawn to weaving two types of randomly-dyed kasuri threads together to create unexpected results. His work, The Peony Pavilion is an example of that method. The works he has presented at this year’s Japan Traditional Kōgei Exhibition incorporate even more new ideas.

“I created them without any kind of planning—even my designs are rough. It was great fun and the things I want to make keep increasing. I have some passion for my work and I think it’s still too early for that to fade.”

The studio where new works are created. (© Kawagoe Yūsuke)

(Originally published in Japanese. Interview and text by Sugihara Yuka and Power News. Banner photo: Tsuchiya Yoshinori together with his work The Peony Pavilion, presented in 2023. © Baba Keisuke.)

Related Tags

kimono living national treasure traditional crafts weaving dyeing