Why Is Annual Income So Low in Japan?

Economy Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Falling Pay in the Far East?

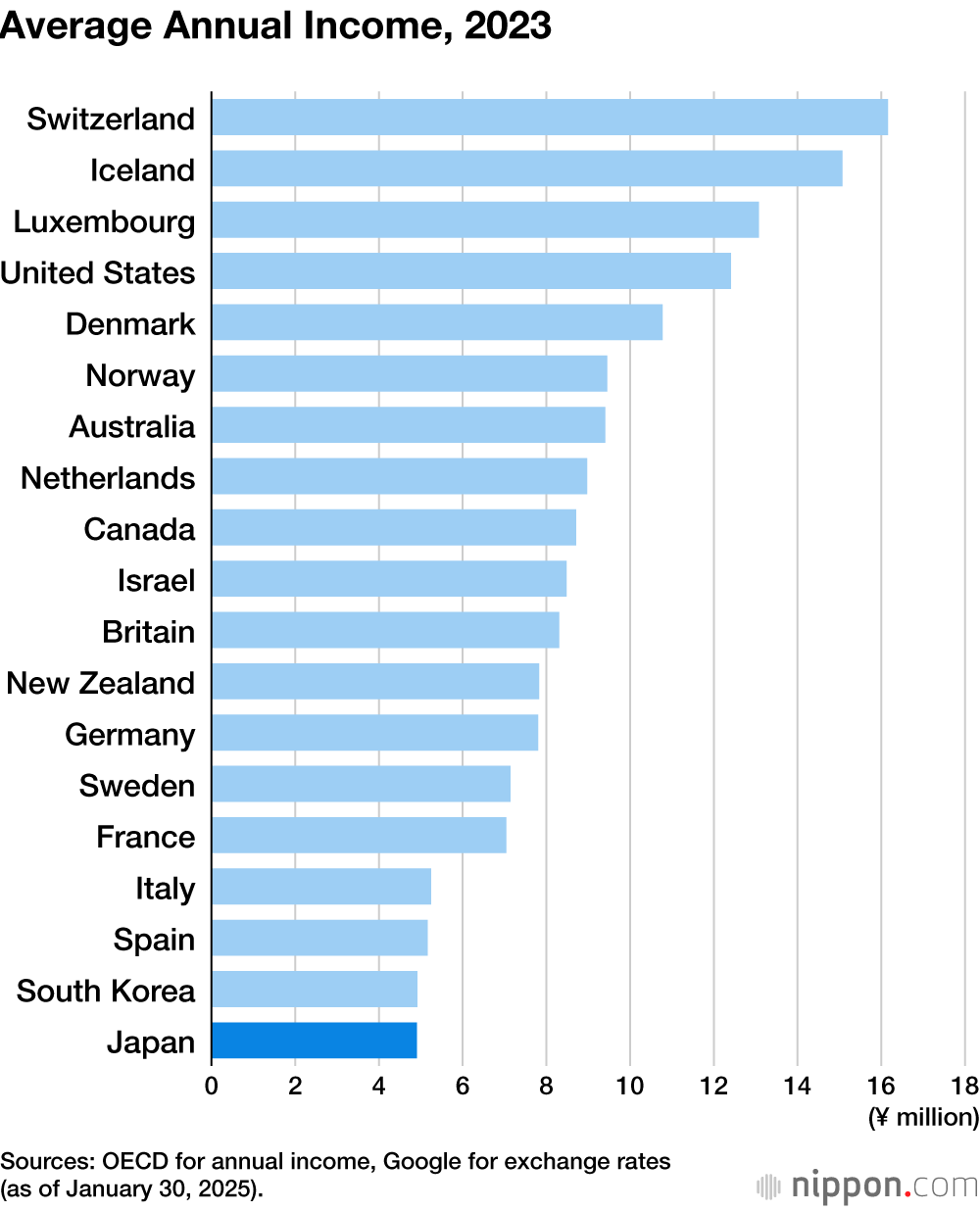

Japan’s average annual income has fallen far behind many other developed countries. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, average income in 2023 was ¥12.41 million in the United States and ¥16.16 million in Switzerland—figures that are 2.5 times and 3.3 times higher, respectively, than the ¥4.91 million in Japan (converted using exchange rates as of January 30, 2025).

Two decades ago, in 2004, Japan’s average was ¥4.66 million, which exceeded the ¥4.50 million in the United States; and while it was lower than the Swiss average of ¥6.98 million, the gap was significantly smaller.

Switzerland is notable, moreover, for its surprisingly high minimum wage. In Geneva and Zurich, for instance, the minimum hourly wage is around ¥4,100—nearly four times Japan’s national average of ¥1,055. This helps to explain why many foreign tourists exclaim that things are “so cheap” in Japan.

A friend of mine from New Zealand, who is now in his sixties and lives in Tokyo, recalls how awesome the Japanese economy appeared back around 1990. Japan’s average income then was 1.9 times New Zealand’s, and it was the prospect of higher earnings that prompted him to move here. The situation today, though, has flipped, with New Zealanders earning an average of ¥7.83 million—a figure 1.7 times higher than in Japan.

When I brought this up with him, he laughingly noted that it looks like he took a wrong turn in life. He has no regrets, though, as he loves the life he has found here, but I could not help feeling a little sorry for him, given Japan’s relative decline, since he had come to this country with such high hopes.

Wages, Cost of Living, and Purchasing Power

Higher wages will mean little, though, if living costs rise even faster. Switzerland, for example, is known for its high cost of living. According to the Big Mac Index published by the Economist, the price of the hamburger in Switzerland is the highest in the world, and is 2.6 times that in Japan. But because average income is 3.3 times higher and minimum wage is nearly 4 times higher, Swiss consumers will likely consider Big Macs to be cheaper than their Japanese counterparts.

What accounts for this gap between the two countries? One factor may be the difference in productivity. Switzerland is home to many highly competitive, blue-chip companies; there are 1.2 Fortune Global 500 companies per 1 million population—four times the Japanese figure of just 0.3. Interestingly, Japan also claimed 1.2 back in 1995, but the decline of consumer electronics, semiconductors, and other industries, coupled with the lack of new growth sectors, has diminished Japan’s global corporate presence.

In 1989, Japan was the top-ranked country in the World Competitiveness Ranking, as reported by the Swiss-based International Institute for Management Development (IMD), with Switzerland coming in second. But Japan has since steadily declined and was ranked number 38 in 2024. While Switzerland’s ranking plummeted for a while, it has consistently remained in the top five since 2008 and has been in the top three over the past five years.

Another stark contrast is fiscal discipline. Budget deficits are, as a rule, constitutionally prohibited in Switzerland, and this has kept populist spending in check. As a result, the ratio of government debt to gross domestic product in 2024 was a remarkably low 32%, compared to 251% for Japan (according to estimates by the International Monetary Fund).

Such differences in economic fundamentals have impacted exchange rates. Both the Swiss franc and Japanese yen were once considered safe-haven currencies during times of financial crises. This is still true for the former, but the yen has lost its reputation as a safe asset over the past decade. The yen’s sharp depreciation in recent years has comparatively pushed down Japan’s average annual income and has weakened its global purchasing power.

The Limited Impact of Monetary Policy

The Bank of Japan had long argued that its ultra-loose monetary policy would help induce a stable inflation rate of 2%, which would then result in a virtuous cycle of higher wages and prices. On January 24, 2025, the BOJ at last hiked its short-term policy rate to 0.5%—the highest level in some 30 years—but monetary conditions remain extremely accommodative. Japan’s real interest rate (the policy rate minus inflation) is −3.1%—far lower than the approximately +1.5% of the US Federal Reserve. Money naturally flows to countries with higher real interest rates, so the BOJ’s policies are now effectively fueling the yen’s devaluation.

Japan has low self-sufficiency in energy and food, so a weaker yen makes such essential imports more expensive. This drives up costs, reduces real wages, and ultimately lowers the quality of life for citizens.

No amount of monetary easing by the central bank will boost productivity. At best, it can prompt a parallel rise in wages and prices, but will not generate sustainable wage growth. Switzerland, like Japan, has low inflation. The average rate of inflation in both countries over the past 20 years has been 0.6%, yet Switzerland boasts the world’s highest wages.

This suggests that achieving the BOJ’s 2% inflation target has little meaning. Of far greater importance is undertaking real-world reforms to enhance Japan’s corporate and workforce competitiveness.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A securities company display in central Tokyo shows the closing Nikkei Stock Average of 39,894.54 on December 30, 2024, the final trading day of the year, along with the yen-dollar exchange rate. © Jiji.)