“Mono no Aware”: The Essence of the Japanese Sensibility

Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Culture and the Words That Tell Its Tales

All words, all languages, change over time. Even so, with perhaps a few exceptions, the feelings that words evoke are more likely to remain the same. Changes in language and changes in feelings are quite different in nature—but in both cases, the speed of change is rather sedate compared to a typical human lifetime.

Of course, this is good news for us. If it were not the case—if words and the feelings they express were rapidly changing all the time—we would have to go back and relearn our mother tongue every few years.

In considering the unchanging sentiments that underlie Japanese culture, the first thing that comes to mind is the Heian period (794–1185). This was a crucial period for the formulation of Japanese culture, and it gave birth to a sensibility that in some ways encapsulates Japanese views of life down to this day.

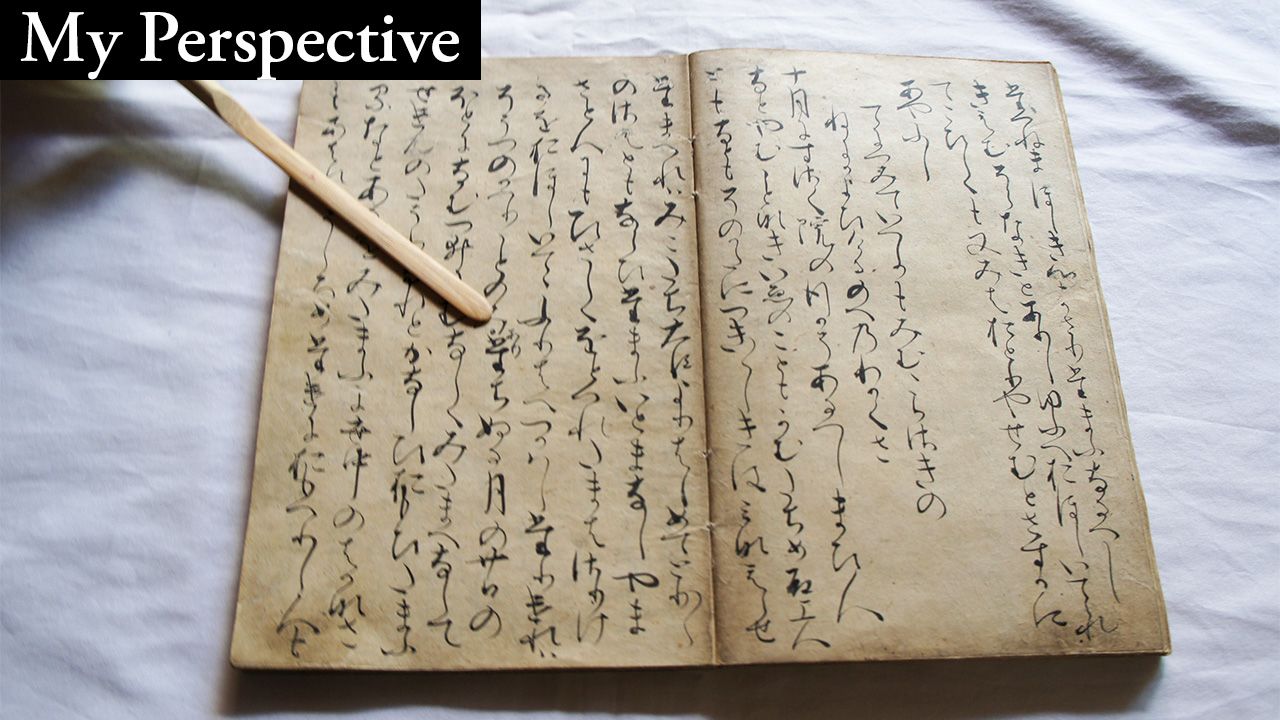

Heian was marked by a remarkable cultural flowering led by women, as seen most famously in literary classics like Murasaki Shikibu’s Tale of Genji and the Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon. Although men in this time occupied a position of unchallenged supremacy in terms of social and political power, when it came to cultural pursuits, the women in and around court outshone the men.

Of course, these men must have been aware of the captivating world that women were creating in their literary works. They must have seen that these tales, and diaries like that of Murasaki Shikibu, Kagerō nikki (trans. by Edward Seidensticker as The Gossamer Years), Izumi Shikibu nikki (trans. by Doi Kōchi as Heian Court Heroines) and others, written largely in the phonetic kana script, captured something that was entirely lacking from the more “serious” writing done by men in classical Chinese. But no one could have foreseen that this nascent literary canon were producing a concept that would play a major role in the formation of the Japanese esthetic sensibility for centuries to come.

The diaries and poems written by women during the Heian era are marked by a common thread—a feeling, difficult to put into words, that became known as mono no aware. This term has been variously translated as the “pathos of things” and as an “empathy” or “sympathy toward things.” It’s a term that is familiar to anyone who has studied Japan and its culture—although even Japanese people might struggle to explain exactly what it means in simple terms.

In fact, the very fact that it is so difficult to explain the worldview expressed by the phrase mono no aware probably reveals an important hidden aspect of the Japanese sensibility in itself. Naturally, for an outsider, grasping the true significance of these feelings is not easy. At its heart, the concept expresses an awareness of impermanence, and a wistful appreciation for the fleeting and ephemeral—for the small things in life, and the realization that, ultimately, we are all destined to fall like the blossoms.

The Lasting Impact of Impermanence

The term aware can be found in texts dating back to mythologies and histories like the Kojiki and Nihon shoki, as well as the poetry collection Manyōshū, but it is in the Tale of Genji that the sensibility reaches its apogee. In other words, the tradition of aware has continued in an unbroken line through Japanese cultural history, from the earliest texts to the present day. It could be described as one of the fundamental values shaping the Japanese worldview and consciousness—both then and now.

Even more than today, Japanese people in those times were attuned to the shifting world around them—the seen and the unseen, the clouds and wind, the blooming and fading of the flowers, and the rippling, shifting course of the rivers and seas—and they perceived these things as inextricably intertwined with the fluctuations of their own inner lives. Like the fleeting loves, lives, and deaths of the characters who appeared in the classic romances of the time, they saw the transience of human life reflected in everything around them, and experienced the bittersweetness of this realization as mono no aware.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A manuscript of the “Wakamurasaki” (Young Murasaki) chapter of the Tale of Genji, containing corrections thought to be in the hand of Fujiwara no Teika. October 7, 2019, Kamigyō-ku, Kyoto. © Jiji.)