Passing On the History of Aggression: Three Generations Sustain Wartime Memories

History Politics Society Family- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A man is talking to a group of high school students in a faltering voice.

“The fate of Japanese soldiers in the Pacific War was wretched. There were about 2.3 million military casualties, but less than half of them died in battle. The others are said to have died from sickness. Japanese casualties reached over 3.1 million including civilians.”

He stresses the number of those who died, and catches his breath.

“But this should not come as a surprise. That war, which Japan started, caused 15 million to 20 million casualties in China and Southeast Asia.”

The speaker is 89-year old Satō Susumu, a resident of the city of Toyama. As a survivor of the bombing of Toyama in World War II, he joins in activities designed to share the fearful experience and the reality of the war with the younger generation.

In February 2023, a group of students from Kanazawa University Senior High School in neighboring Ishikawa Prefecture visits Satō at his home with their teacher to learn about his experiences. Before he tells his personal story, Satō explains the historical facts of the Pacific War and gives an overall picture based on materials he has gathered. Using his computer, he shows them video footage from television reports while carefully explaining the chronology of the war, emphasizing that it was started by Japan.

Satō Susumu (right) gives clear answers to the questions from the Kanazawa University Senior High School students at his Toyama home. (© Miyazaki Takahiro)

Speaking between the clips of footage, his solemn tone leaves a deep impression.

“We must not forget that, while Japanese people were victims, we were also the perpetrators of that war.”

The Bombing that Decimated Toyama

Satō began his speaking activities in 2001. He was asked to share his experience of the city’s bombing by local children, after which he was invited to speak at elementary and junior high schools. This led to many more opportunities to present at schools: around 260 times up to the end of 2023. Some 20,000 students have now heard Satō share his story and his presentation on the facts of the war.

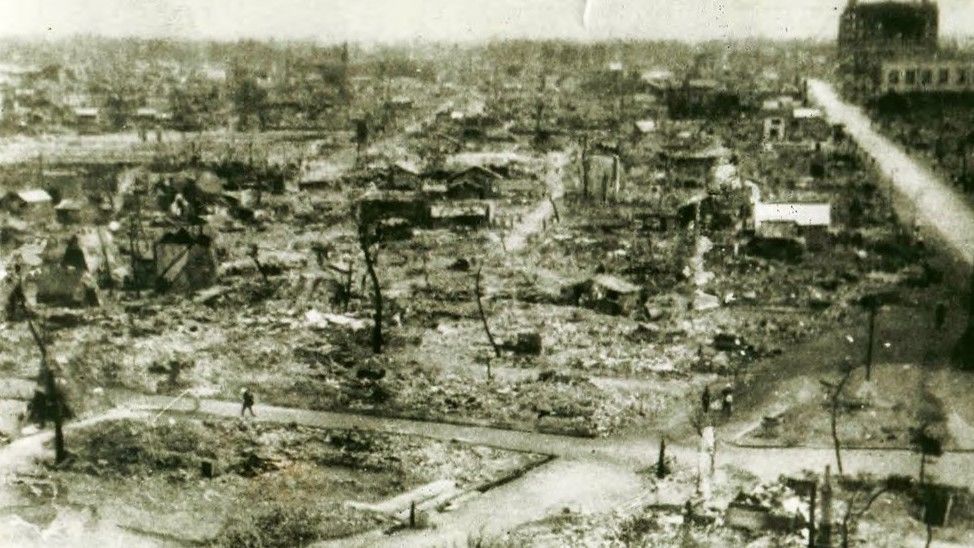

The bombing of Toyama occurred in the predawn hours of August 2, 1945, with 182 US Air Force bombers attacking Toyama over a two-hour period, dropping a total of more than 1,400 tons of incendiary bombs, burning the city to ashes.

The charred ruins of the Sōgawa shopping street, as pictured in Toyama daikūshū (The Bombing of Toyama). (© Kitanippon Shimbun)

Japanese history tends to focus on the air raids targeting major cities, such as Tokyo, but damage assessment by the US military estimated that 99.5% of Toyama was destroyed, ranking it as one of the worst-hit cities. Incidentally, the US Air Force also bombed the cities of Mito (Ibaraki), Hachiōji (Tokyo), and Nagaoka (Niigata) that same morning. The New York Times described the bombing of the four cities as “the mightiest single air blow ever struck.”

At the time, Toyama was an industrial center, with companies such as Nippon Soda and Fujikoshi producing chemicals and machinery for use by Japan’s military. Satō’s father belonged to a naval band, based in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture, but following the breakout of the war, he was assigned to the brass band of the Fujikoshi plant, and his family was also relocated to Toyama. At the time of the bombing, Satō was 10 years old.

In his hands, Satō has a photo taken by US forces prior to the bombing, using flares to light up the city. At the time it was taken, Satō was sheltering in the family’s home. “This was my house. It’s painful to look at, because it’s quite clearly visible.”

On the night of August 1, he was woken by air-raid sirens, but they soon stopped, and, feeling assured, he crawled back into his futon and fell into a deep sleep. But soon after midnight, bombers did arrive, and soon, fierce fires spread across the city from the west.

He fled with his mother and siblings to a rice field near the house, and as they crouched under futons for protection, he heard a loud thumping: the sound of bombs hitting the mud in the rice paddy. Luckily for him, the mud delayed detonation of the incendiary bombs.

“Just then, I heard someone shout: Jump into the river! Without a second thought, my brother and I jumped in. My sister had strained her lower back in the mud, but my mother managed to help her into the river too. If they had been any slower, they would have perished. I should have been looking out for them: Even now, I regret my actions at that moment.”

“I Thought Japan Was the Victim”

The incendiary payload dropped on Toyama burned the city to the ground. Fire spread close to the river where Satō and his family cowered under their wet futons until the flames receded.

“When the sun came up, we were greeted with the shocking sight of the smoldering ruins. Our home had also burned down, and there were dead bodies strewn about. I saw the remains of many small children. Soon after, dozens of corpses washed ashore in the nearby city of Himi. I heard they even found a young mother holding her newborn baby.”

Satō continues his graphic account of the hellish scenes of the bodies that floated down the Jinzū River into Toyama Bay, before they washed ashore on the coast of Himi, on the lower Noto Peninsula.

“Try to imagine the consequence of bombing a densely populated residential area. Even in war, there are rules against attacking civilians. But Japan and Germany were the first to break these rules. Later, America did too. That’s what war is.”

Satō’s narration places the bombing of Toyama within the context of Pacific War chronology. He studied the history of Japan’s aggression of his own volition, visiting battle sites in Okinawa and the Pearl Harbor National Memorial, on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, gradually gathering more information for his talks.

After listening to Satō for almost an hour, the students meekly share their impressions with him.

“To be honest, I thought Japan had been the victim in the war.”

“I feel I’ve heard the true history of the war, something I didn’t learn from school textbooks.”

Echoes in Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

Two women who are sitting alongside Satō, ardently taking notes. One is his daughter, Nishida Akiyo, and the other is her teenaged daughter Nanako. They are currently learning from the aging Satō, hoping to carry on his work.

For the past five years, Sato’s health has been faltering, and Akiyo suggested he should stop giving talks. His response was “It’s my mission,” leading Akiyo to consider what she could do to help.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 spurred her into action.

A news flash reported that Ukraine’s capital Kyiv had been bombed, and Russian ground troops had crossed the border, invading eastern Ukraine. The television showed piles of rubble, reminding Akiyo of her father’s descriptions of World War II. She recalls, “I felt I couldn’t stay silent,” and she wondered what to do.

Soon after, she read online of a project in Hiroshima training people to continue sharing the stories of hibakusha (atomic bomb victims). The city of Hiroshima launched the project in 2012 as a way of ensuring that the stories of victims would continue being shared with future generations. Initially, two groups were engaged in bearing witness to the atomic bombing: actual survivors, and “memory keepers.” Since 2022, the city has also started training a new group, known as “family witnesses,” children and grandchildren of hibakusha who are accredited to relay the stories following two years of training.

Nishida thought, “That’s what I could do,” and she also asked her daughter if she was interested. Nanako’s response was immediate: “Yes, I’ll do it!” She was also agonized by the news of the Russian invasion.

Satō’s granddaughter Nishida Nanako (center) and daughter Akiyo listen closely to his recollections. (© Miyazaki Takahiro)

The media showed young children in shelters crying “I don’t want to die,” or walking through the ruins.

According to Nanako, “After learning there are children just like me who are caught up in war, it feels wrong to ignore it. Doing nothing at all is the same as tolerating the violence. I want to do what I can to make sure that the people who died or were injured in the war aren’t forgotten.”

A Study Visit to Okinawan Battlefields

Nishida and her daughter began accompanying Satō when he gave lectures, for “training.” In February 2024, the three traveled to Okinawa to visit former battlefields.

The trip was Satō’s suggestion. “Carrying on my activities requires broad knowledge. Okinawa is the only part of Japan that experienced land battles during the war. I want people to know how Japan’s military leaders, the Imperial General Headquarters, exacerbated the devastation in its attempt to slow the US forces even slightly.”

US forces use a flamethrower to attack Japanese troops and civilians hiding in a cave during the Battle of Okinawa on June 25, 1945. (Collection of the Okinawa Prefectural Archives)

They visited the Tsushima-maru Memorial Museum in Naha, dedicated to a ship that was evacuating hundreds of schoolchildren from Okinawa to Nagasaki when it was sunk by the US military, resulting in over 1,500 casualties. Later, they went to the Himeyuri Peace Museum in Itoman, which bears witness to the horrific conditions faced by school students who were mobilized to act as nurses on the battlefield. The three made another stop at the Urasoe Castle ruins, the scene of fierce fighting in 1945, and passed the imposing US Marine Corps Air Station Futenma nearby as they drove northeast on National Route 58.

American forces carry a colleague killed in action close to the Urasoe Castle ruins during the Battle of Okinawa on April 22, 1945. (Collection of the Okinawa Prefectural Archives)

Midway through their trip, Satō became unwell, and was briefly hospitalized. After returning, in June 2024, Nishida Akiyo gave a lecture on behalf of her father, who had not yet fully recovered, and in July, Nanako gave her first talk to students at an after-school facility.

According to Nishida, “I knew this day would come. I still feel under-prepared, and am no match for my father, but I’ll do my best to keep learning so I can keep his story alive.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Research and interviews by Power News. Banner photo: The view of Toyama from the roof of the Toyama Electric Building immediately following the firebombing of the city, from Toyama daikūshū [The Bombing of Toyama]. © Kitanippon Shimbun.)