The Noborito Research Institute: Catalyst for Peace Education

History Society Politics- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Meiji University’s Ikuta campus is situated in hilly terrain in the Kanagawa Prefecture city of Kawasaki. Scattered around the campus are remnants of old buildings with special historical significance. There are, for example, a fire hydrant bearing the five-pointed star emblem of the Imperial Japanese Army, a huge cenotaph to animals, and boundary markers with the word “Army” carved onto them. These are all vestiges of the Army Ninth Technical Research Institute, usually called the Noborito Research Institute, which was run there by the Imperial Japanese Army from 1939 to 1945.

A boundary marker near the museum. (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

The site, briefly occupied by Keiō University and the Kitasato Institute after the war, was acquired by Meiji University in 1950. Some of the buildings were preserved as is and one now houses the Noborito Laboratory Museum for Education in Peace, at the southern end of the campus. Boundary stones, a fire cistern, and a munitions depot dating from the war surround the building, which formerly housed a research laboratory focusing on biological and chemical warfare.

An exterior view of the museum. (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

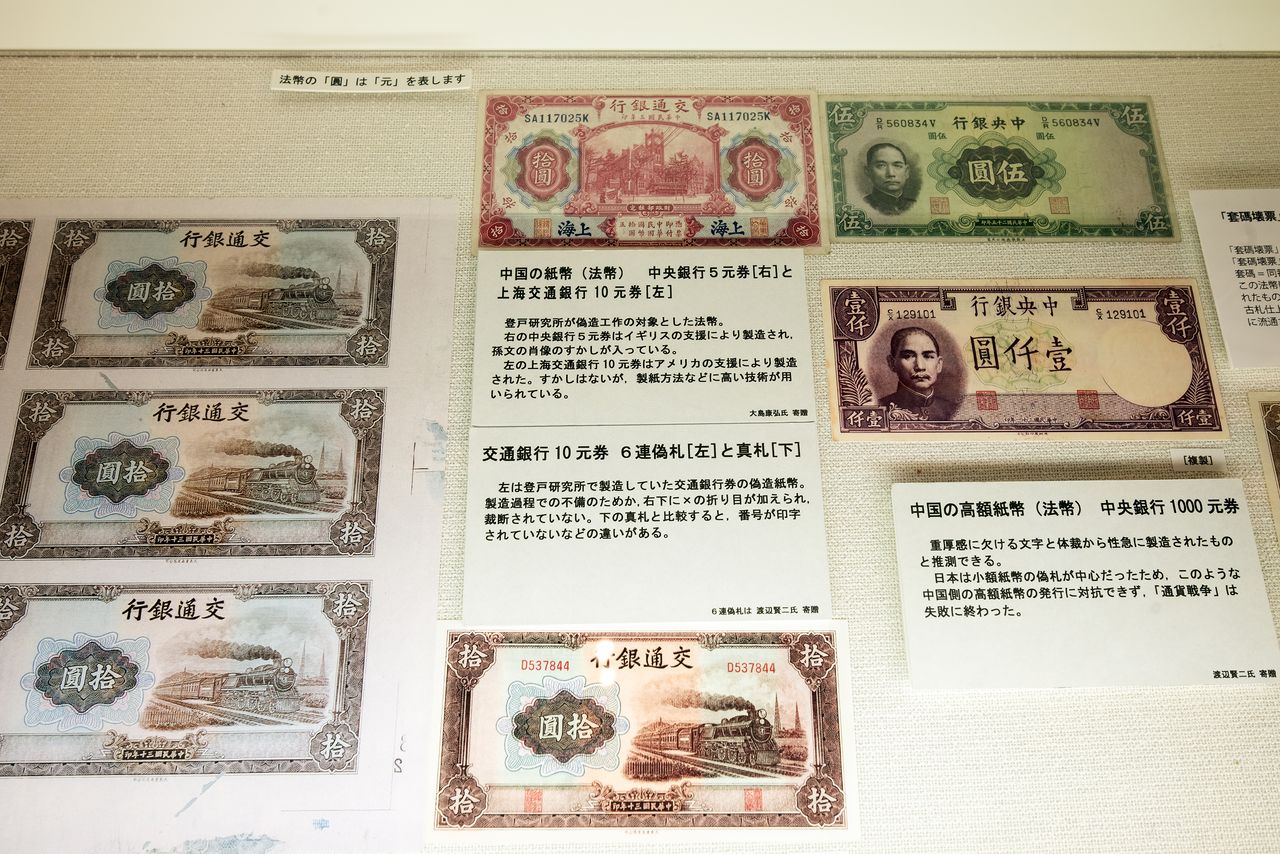

The Noborito Research Institute, occupying a 33-hectare site now inside the larger Meiji campus, was set up in 1939. Its purpose was to research and manufacture weapons for covert operations, ranging from chemical and radio-wave weapons to incendiary balloon bombs and counterfeit Chinese currency, all of which were actually used during the war.

The Institute manufactured nearly 10,000 balloon bombs, each measuring 10 meters across. The balloons were floated from Japan’s Pacific Ocean coast to the United States; 1,000 of them reached North America. Counterfeit currency in an amount equivalent to ¥4 billion was produced, intended to destabilize enemy countries’ economies and actually circulated in China.

A mock-up of a balloon bomb. (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

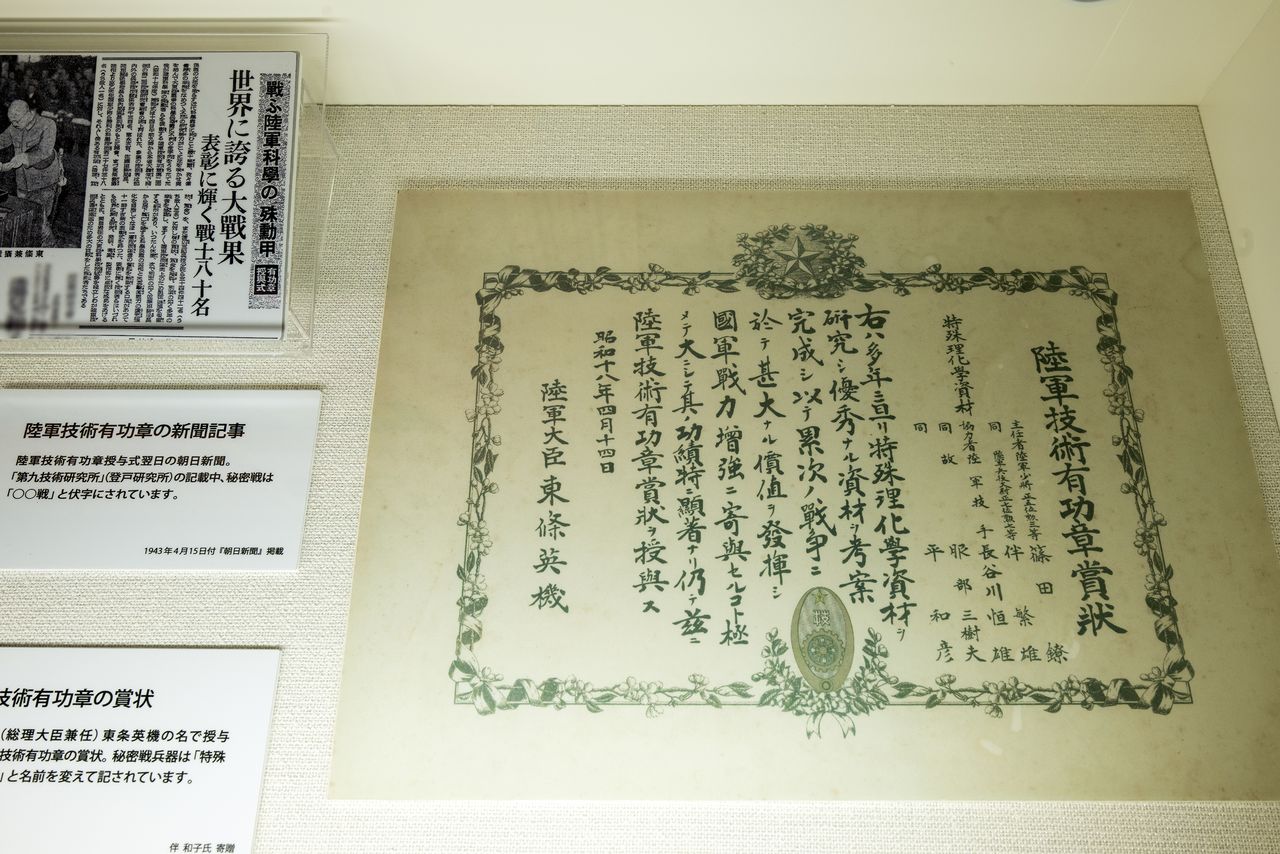

In addition to the balloon bomb mock-up, the museum displays a certificate of appreciation from wartime Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki congratulating institute members for their work developing poisons.

The certificate from Prime Minister Tōjō Hideki. (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

Each of the exhibits is carefully described, but the museum labors under a difficulty. As Meiji University professor and museum director Yamada Akira explains, “One of our museum’s weaknesses is a paucity of original materials. Since the Noborito Institute was engaged in covert warfare activities, all evidence was destroyed or burned after the war, so we have few original artifacts or papers to display.”

“Destroy All Evidence”

At the Institute, up to 1,000 local inhabitants worked as assistants under the direction of 100 or so technical officers. With the war nearing its end in 1945 and an invasion of mainland Japan seemingly inevitable, the Army split up and moved the institute’s functions to other parts of Japan, such as Nagano and Fukui Prefectures. On the morning of August 15, the day Japan’s unconditional surrender was to be announced, the Army General Staff issued an order to destroy all evidence of the facility’s covert research so that it would not fall into the victors’ hands. Workers hurriedly carried out the order, and many of them died without ever speaking of their work.

It was only some 40 years later, in the mid-1980s, that the veil of secrecy surrounding the Institute was finally lifted. High school students provided a breakthrough.

In 1988, a group of local citizens involved in historical research, the Kawasaki Nakahara Heiwa Gakkyū (peace academy) , led by former high school teacher Watanabe Kenji placed an announcement in newspapers and organized several visits to the institute site. Watanabe did so in the belief that some people with knowledge of the history there might come forward.

Watanabe Kenji, the instigator of research into the Noborito Institute. (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

On the fifth such visit to the site, an elderly man offered that he had created a list of co-workers at the institute. He had compiled the list in the hope of seeing his colleagues again and recapturing a part of his youth. The high school students in the study group created a questionnaire that they sent to the 90 or so people on the list, receiving 20 or so responses. One respondent, a woman who had been employed as a typist at the institute, gave the group a sheaf of documents she had surreptitiously taken home to practice her typing skills.

The broadcaster NHK aired a documentary on the Kawasaki citizens’ move to unearth this wartime history. After seeing the program, students from Akaho High School in Komagane, Nagano Prefecture, began a project to collect eyewitness accounts about the institution, part of which had been moved to their town. They visited the institute’s neighborhood, where they encountered an old man who volunteered that he had worked there. After several visits by the students to the man’s home, he decided that he would tell them his story.

That man was Ban Shigeo, the institute’s director of research and development into covert operations who had considerable experience working alongside Shinoda Ryō, who worked with the institute’s predecessor organization, the Army Science Research Institute, and headed the facility up to the end of the war. In 1989 Ban began telling the students about the institute’s work.

Revealing a Taboo Subject

Ban had not initially been ready to talk, but when the students visited him at his summer home in Nagano Prefecture, he realized that the time had come to unburden himself. This is what he says in Rikugun Noborito Kenkyūjo no shinjitsu (The Truth About the Army Noborito Research Institute).

“Some young people ask, straight-faced, ‘Did Japan really go to war with the United States?’ Before we laugh at their ignorance, it behooves us to realize that this generation, the grandchildren of those who lived through the war, can only conceive of war as something that happens somewhere else, in some other far-away country.”

Yamada suspects that Ban felt that this contact with a generation who really knew nothing about the war no doubt brought about a change of heart in those who had remained silent before. If Ban did not talk now, the truth about the war would be buried forever; talking about it was a vital way of passing on a part of history.

Museum director Yamada Akira believes it is important to talk frankly about the war in order to pass on the lessons of history. (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

Ban wrote his book four years after being interviewed by the students. In it, he described experiments with poisons and radio-wave weapons and the manufacturing of counterfeit currency in detail, as he had related to the students. But the book also describes one secret he had felt unable to reveal to them.

Filter tubes of a type actually used on World War II battlefields in Ban’s possession, stamped “military secret.” (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

Human experimentation had been conducted in China with a poison that Ban had developed at the Institute; he attended experiments conducted by Unit Ei 1644, a satellite unit of the infamous Unit 731. His book describes in detail how the poison was administered to Chinese prisoners of war and death row criminals, as well as the research conducted into lethal doses and manner of death. The writing is unemotional, but Ban concludes with the following words of remorse.

“War’s dark side has been buried up until now . . . but it is time to fill in the gaps in history, pray for the souls of those who were experimented on, and hope for peace from the bottom of my heart.”

Ban passed away suddenly in November 1993, soon after completing his manuscript. Published after his death, it lays out the historical facts. The truth was saved from being lost forever.

Yamada says, “Young people who have never experienced war did a superb job of digging up memories. Without the statements they collected in their interviews, we could never have created the museum.”

Artifacts Turn Up by Chance

Yamada takes every opportunity to remind others that it is important for people who did not experience the war to probe memories. It is often the case that previously concealed information turns up simply by chance.

”When museum staff preparing a themed exhibition contacted the paper-maker Tomoegawa Corporation to ask whether any records of the wartime era remained there, a employee there mentioned that a sheaf of paper for making reserve notes had turned up in one of their storerooms, and that it might have something to do with the Institute.”

Reserve notes were a currency issued by the Empire of Japan’s puppet state in China headed by Wang Jingwei (1883–1944). Since these were worthless anywhere outside of territory occupied by Japan, the Institute had been making counterfeit currency imitating China’s legal tender to enable economic operations in Chinese-controlled territory as well.

The file that turned up in Tomoegawa’s storeroom contained research on creating watermarks and inserting thin silk threads into banknotes, essential techniques for creating convincing versions of legal tender.

Counterfeit currency materials donated by Tomoegawa Corporation. (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

“The newly-found documents explained how during the war, Tomoegawa had spent a year developing a watermark for banknotes bearing a likeness of Sun Yat-sen [1866–1925]. It also contained actual examples of the banknotes, so progress in mastering the technology could be observed. This was top-secret stuff that only the company head would have been likely to know.”

This material might have been destroyed if someone in the know had come across it. Luckily it was discovered by a person who had not lived through the war but who intuited that it might be valuable documentation. Yamada hopes that more such materials will turn up in a similarly fortuitous manner.

Panels in the museum’s exhibit space. (© Yokozeki Kazuhiro)

(Originally published in Japanese. Reporting and text by Hamada Nami and Power News. Banner photo: Director Yamada Akira poses in the museum. © Yokozeki Kazuhiro.)