Ships on the Seabed: Searching for the Mongol Empire’s Lost Invasion Fleet

History Society Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Warships to Japan

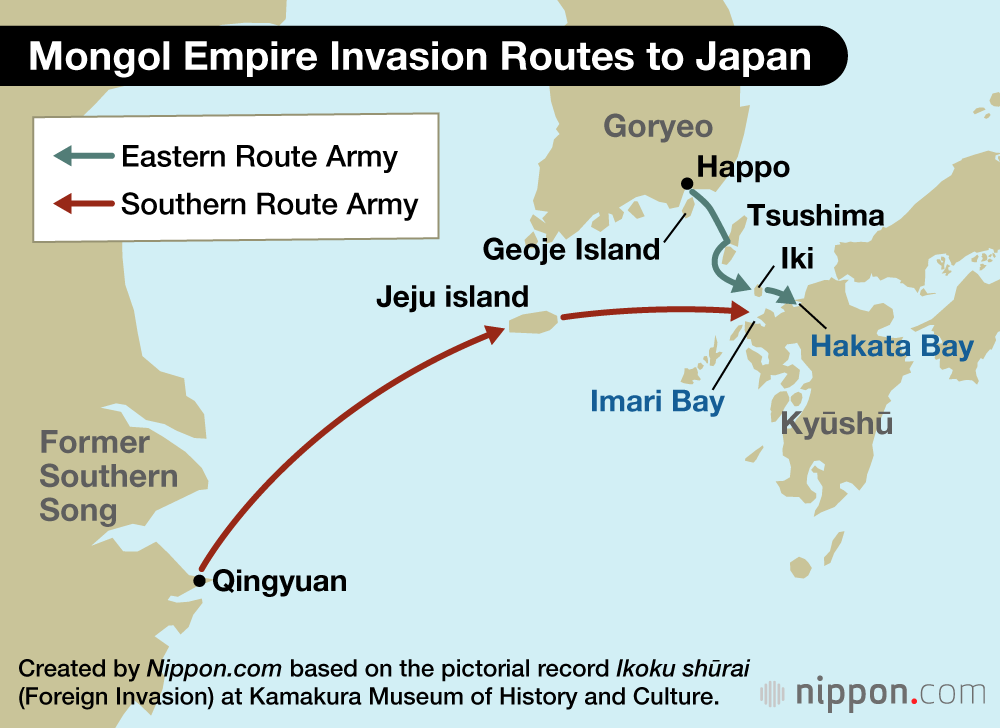

After a first failed invasion of Japan in 1274, Mongol leader Kublai Khan, founder of the Chinese Yuan Dynasty, sent a second wave of troops in 1281. Ships carrying Yuan soldiers traveled in two groups: the Eastern Route Army that departed from the Mongol vassal state of Goryeo on the Korean Peninsula, and the Southern Route Army, which left from recently conquered territory of the Chinese Southern Song dynasty.

The two invading forces were to assemble at the island of Iki for an assault on Kyūshū and the regional center of Dazaifu. However, the strategy ran into trouble as the Southern Route Army departed a month and a half after the Eastern Route Army. If the plan had been better coordinated, the warships would have filled Hakata Bay, and Japan would have faced a greater threat. As it was, the Southern Route Army is thought not to have reached Hakata Bay at all, but instead touched at Imari Bay some distance to the west where it was devastated by a typhoon.

Searching the Seabed

Nearly eight centuries later, these sunken ships were finally discovered.

For some time, around the mouth of Imari Bay at a location known as Takashima Kōzaki, fishermen had found pots, weapons, and other items that seemed to be from the Yuan invaders. During port reconstruction work from 1994 to 1995, large numbers of such items emerged, and momentum gathered for searching for the ships themselves. A full scale archaeological survey of the seabed was launched in 2005.

Clockwise from top left: A seal inscribed with Mongol script found at Takashima Kōzaki that is thought to belong to a company commander; lacquered combs; and bronze fixtures Mongol Empire soldiers attached to their belts from which to hang their weapons. (All courtesy Matsuura City Archaeological Center in Nagasaki Prefecture; © Nippon.com)

Finding the lost vessels was a challenging task. “We assumed that there were large numbers of sunken ships,” explains Professor Ikeda Yoshifumi of Kokugakuin University, who was involved in the survey. “But no matter where we searched, nothing turned up. The wooden vessels that were exposed to seawater had been eaten up by shipworms.”

Professor Ikeda Yoshifumi of Kokugakuin University. (© Nippon.com)

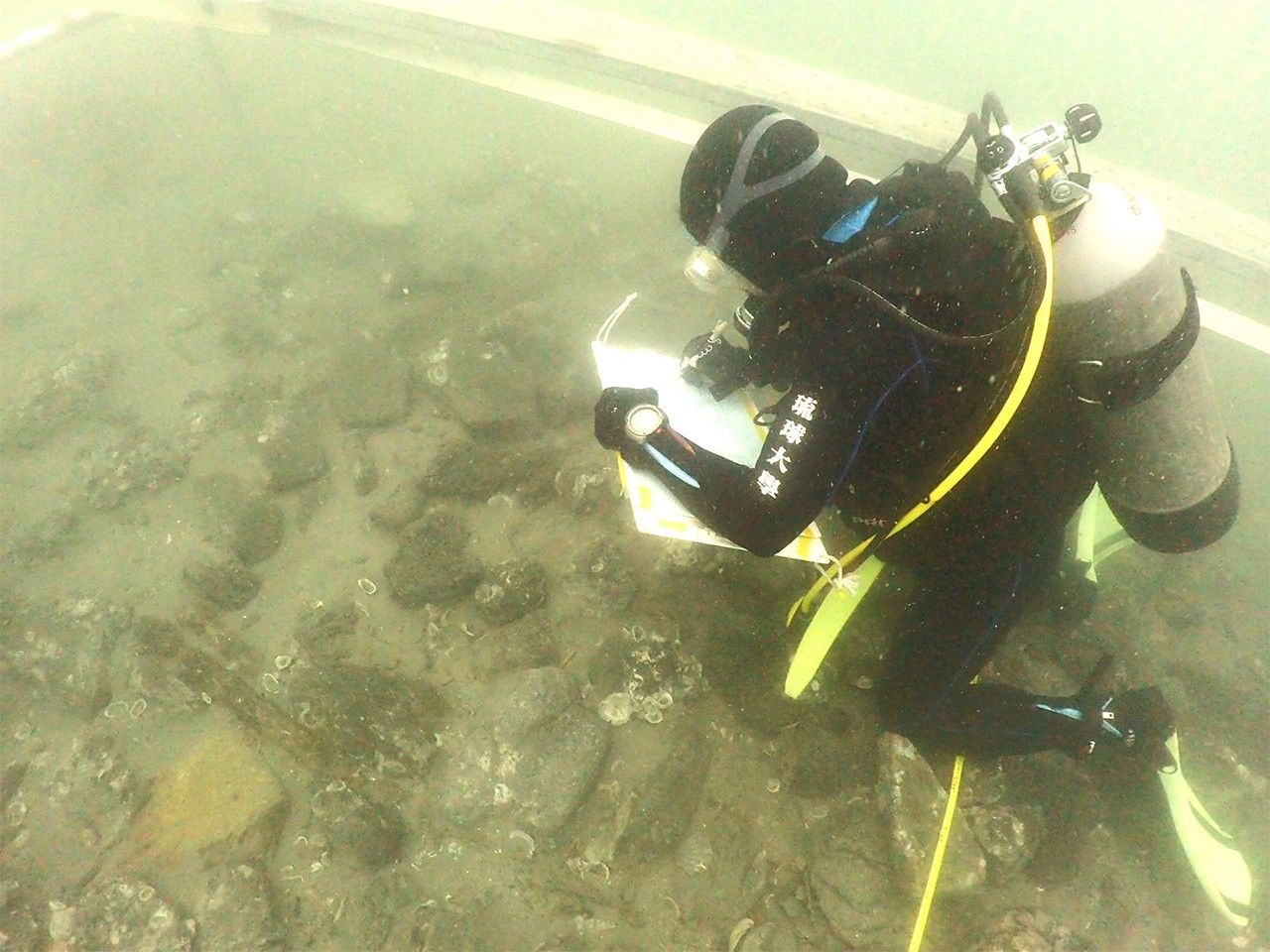

All was not lost, though. If the sea currents had buried some of the ships in sediment, there was a good chance that they were preserved. The survey team, centered on Ikeda—who was then working at the University of the Ryūkyūs—used sonar devices over several years to create maps of the seabed and its faults. The team discovered more than 100 places with irregularities in this manner.

Ikeda led a team of divers to investigate each of the locations. Armed with an iron bar, he would strike the seafloor, and from the sound he could tell if the items that laid beneath were shells, materials like ceramics, or wood.

Ikeda investigates the seabed during the survey. (Courtesy Matsuura Board of Education)

A Sense of Relief

After five years of work, Ikeda and his team in 2010 found wood that seemed to be part of a shipwreck. Although the pieces at the site were scattered on the seafloor, Ikeda confirmed the following year that they belonged to a ship with an estimated length of 27 meters. “We’d been plagued by doubts for six years, wondering if there really were ships at all,” Ikeda recounts. “It was a great sense of relief to find such unmistakable evidence.”

A view from above of the first sunken ship discovered. (Courtesy Matsuura Board of Education)

In 2015, a second ship with an estimated length of 20 meters was found. Wood that appears to be from a third ship was discovered in 2023 and is currently being studied. Both the first two vessels were identified as belonging to the Southern Route Army, due to their V-shaped or rounded bottoms and bulkheads that partitioned the cabins. The difference in the ships’ sizes appears to be connected to the different purposes they served. Many ceramic items from the former Southern Song were also found around the vessels.

A computer-generated image shows how the Mongol warships are thought to have looked. (Courtesy Matsuura Board of Education)

Ikeda explains that historical artefacts typically decay quickly on land, where they are exposed to the ravages of nature. “If buried in mud on the seabed,” he says, “they become sealed as if in a time capsule.” He continues to work to further uncover the history of the sunken Mongol fleet.

Anchor Stones

The island of Takashima in Nagasaki Prefecture is home to the Matsuura City Archaeological Center, which enjoys a picturesque view of nearby Imari Bay.

Uchino Tadashi, the director of the cultural properties division of Matsuura Board of Education, guides me around the center. “As well as planks from the Mongol ships, some parts of anchors have also been discovered on the seabed,” he says, pointing at a cylinder-shaped stone section about a meter long. The anchors of the Mongol ships were made of a V-shaped section of wood, with two stone weights attached.

The heaviest stone weighs more than 170 kilograms. Uchino explains that the wooden part is typically destroyed by shipworms, leaving only the stone. So far 36 stones have been found.

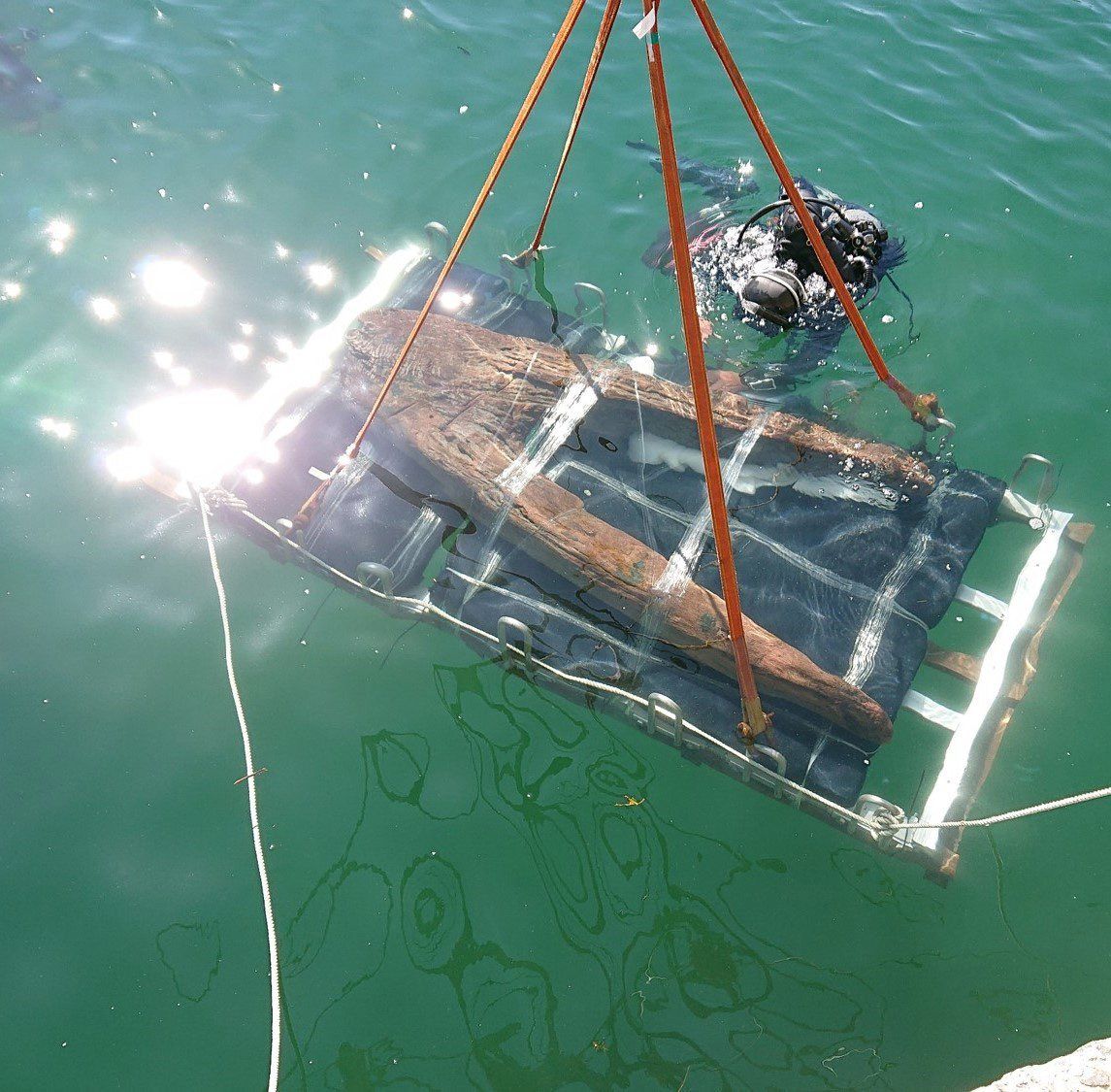

A stone and wood anchor salvaged in 2022. It is unusual as it has only one anchor stone. (Courtesy Matsuura Board of Education)

Anchor stones at Matsuura City Archaeological Center. (© Nippon.com)

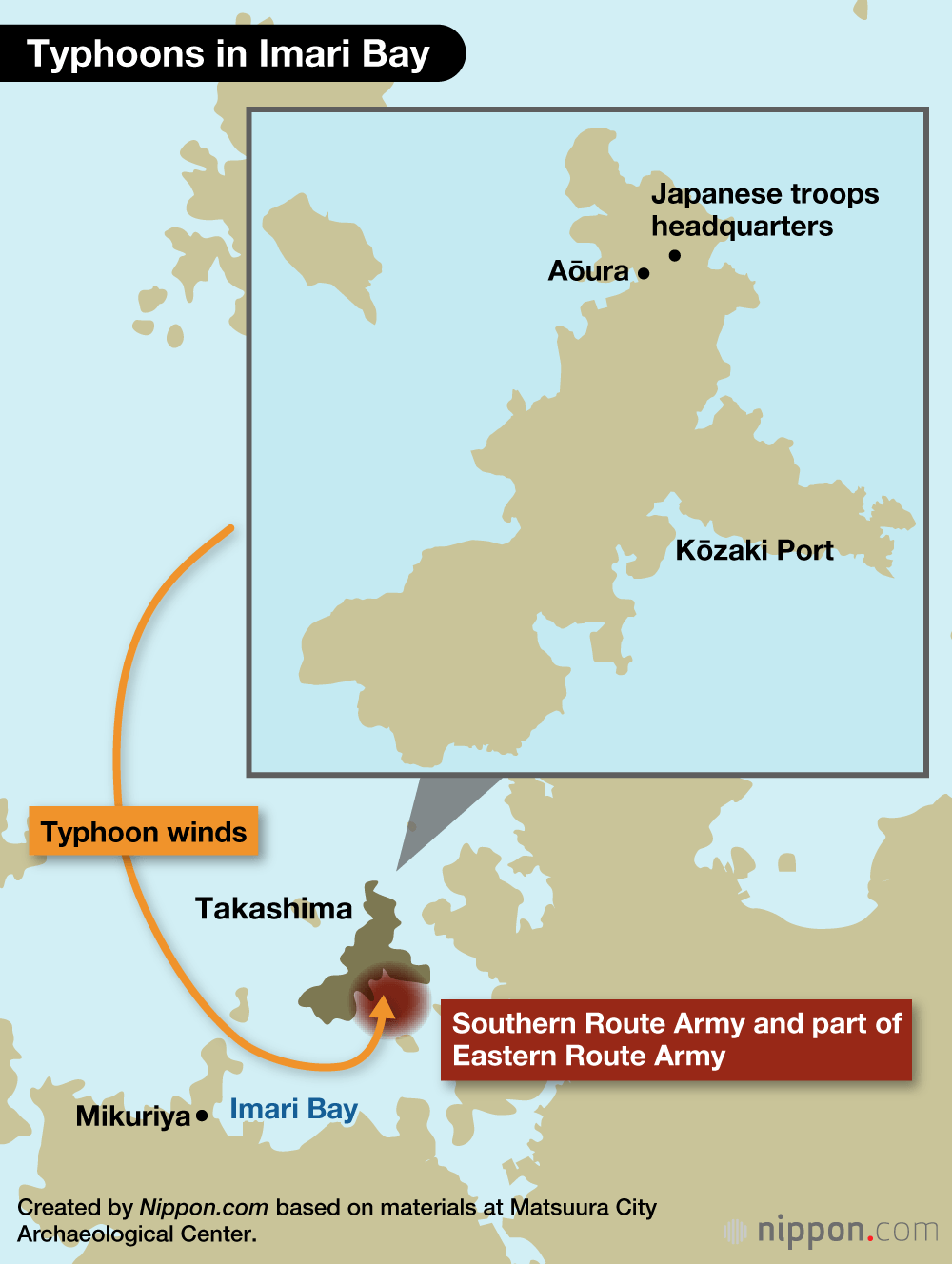

In 1994, reconstruction work at a port on the island uncovered four V-shaped wooden anchors that were lined up intact. All four pointed south, but there was no sign of any ships. Ikeda speculates that they were dragged from south to north by the tremendous power of a typhoon before breaking loose from their vessels.

Ships that lost their anchors seem to have been blown north. For instance, the first two ships discovered were both on the northern side of Imari Bay. The fleet carrying the Southern Route Army is said to have comprised 3,500 ships. Ikeda says, “As they were carried to the north, all packed together, knocking against and crashing into each other, they must have suffered tremendous damage.”

The island sets in the entrance of Imari Bay to the north and serves as a breakwater, keeping the waters of the bay relatively calm. However, residents say that when typhoons move past Tsushima, winds are known to blow furiously from south to north, whipping up the waters of the bay. It seems probable that these were the conditions that confronted the Mongol fleet upon arriving at Takashima.

Graves and Monuments

Archaeological evidence supports the idea that strong winds sunk the ships. Historical records indicate that most of the Southern Route Army troops perished in the waves, but some washed ashore at places like Takashima and Mikuriya.

“Records show that the commanders boarded the boats that were still usable and returned home,” Ikeda says. “The troops left behind reached land, but as they were mostly unarmed, they were no match for the shogunate soldiers tasked with conducting mopping-up operations.”

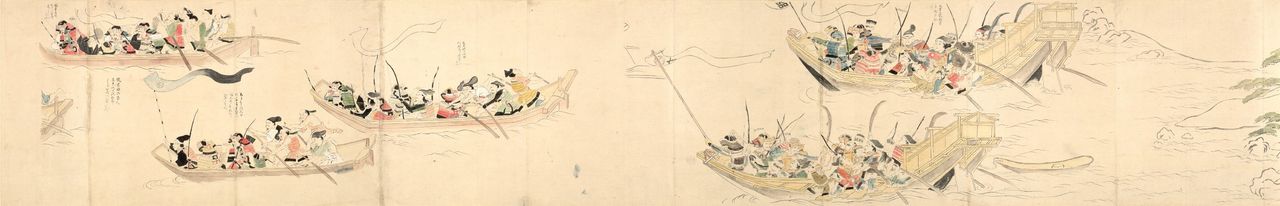

A copy of Mōko shūrai ekotoba (Illustrated Story of the Mongol Invasions) depicts shogunate troops dispensing with the remnants of the shattered Yuan army. (Courtesy Kyūshū University Library)

Kiyama Tomoaki of Matsuura City Archaeological Center explains that the Kamakura shogunate troops had their headquarters in the north of Takashima. “Aōura in the west is said to have seen the fiercest fighting.”

The Ryūmen’an hermitage was the shogunate headquarters. (© Nippon.com)

Although the shogunate emerged victorious, there were numerous casualties on the Japanese side. Islanders and soldiers alike lost their lives, and there are many graves and stone monuments scattered across the island.

The grave of Hyōe Jirō. After traveling from Tsushima to warn the shogunate at Dazaifu of the Mongol attack, he died in battle on Takashima. (© Nippon.com)

Destruction or Retreat?

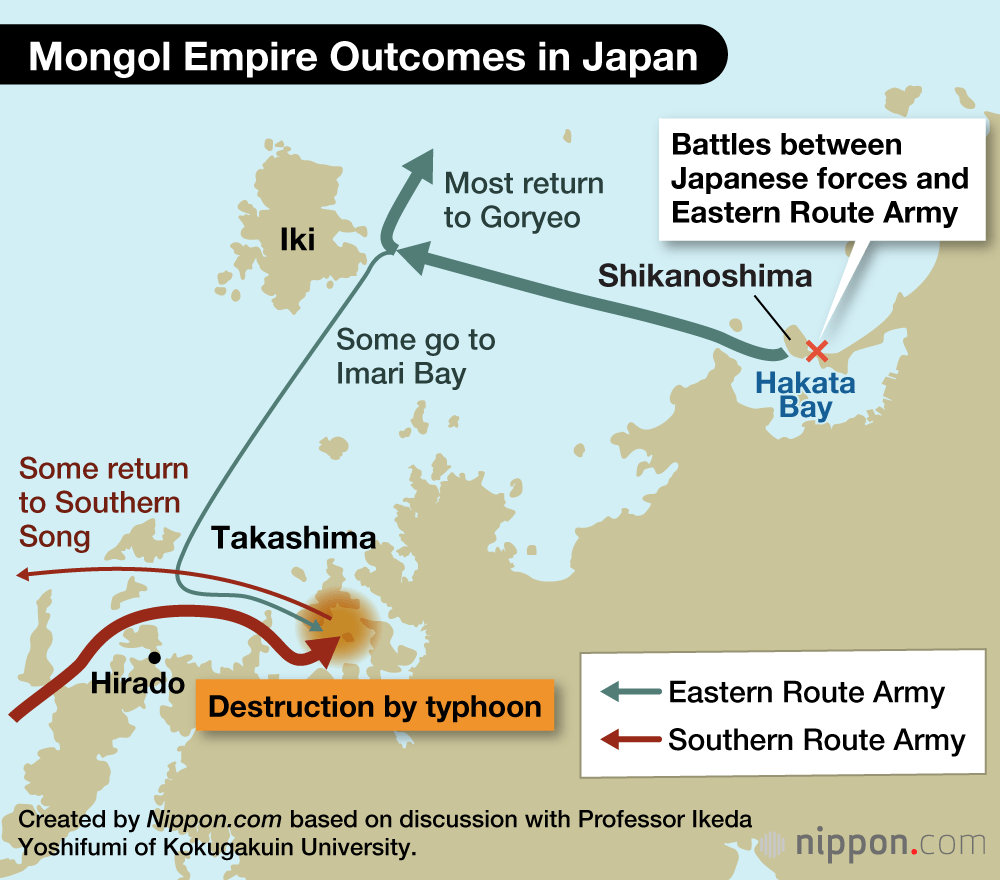

The Eastern Route Army fared better and managed to enter Hakata Bay, although it waited in vain for the Southern Route Army’s arrival. Bulwarks constructed along beaches prevented the troops from advancing onto the land, forcing the army to make its base at Shikanoshima, an island near the entrance to the bay. Persistent night attacks and other actions by shogunate soldiers took their toll on the invaders. Eventually, damage to ships and sickness among its troops forced the Eastern Route Army to retreat to Iki for supplies.

The commonly accepted theory is that the two armies joined there, but were battered by typhoons at Imari Bay. Ikeda, however, says that a historical record of Goryeo states that 80% of the Eastern Route Army returned home to the Korean Peninsula. “While some went to make contact, heading to Imari Bay, it could be that many ultimately continued north from Iki and went back to Goryeo.” The paucity of Goryeo artefacts found in Imari Bay matches this suggestion. When news came of the destruction of the Southern Route Army fleet, they may have abandoned their military goals.

The Mongol Empire grasped much of the Eurasian continent in the course of less than a century, thanks to the superiority of its mounted troops. It had no experience of sea battles though, meaning that it relied on Goryeo and Southern Song to build a fleet and provide much of the fighting force. These soldiers had no choice but to fight for the occupying empire, and may not have had high morale. The Mongol Empire, invincible on land, struggled over the sea and met the irresistible force of a typhoon, suffering what might be seen as its first crushing defeat. After two attempts, it gave up on conquest of Japan.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner image: An aerial view of the sunken second Mongol ship. Courtesy Ryūkyū University and Matsuura Board of Education. Photograph and editing by Machimura Tsuyoshi.)