“Moyashiya”: Japan’s Centuries-Old Merchants of “Kōji” Mold

Food and Drink Culture Health Environment History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Kōji as the Cornerstone of Japanese Food Culture

Kōji is produced by cultivating the mold Aspergillus oryzae on steamed rice, barley, or other cereal. When rice (kome) is used, it is known as kome kōji, and so on. Of the different varieties available, kome kōji has the most practical uses for home cooking, and is widely available in supermarket pickles sections.

Kōji is the cornerstone of Japan’s food culture. Common Japanese condiments, including soy sauce, miso, and mirin, are fermented food products manufactured using kōji. The prevalence of fermented foods in Japan can partly be attributed to its warm, humid climate. A broad range of the country’s diverse and distinctive regional pickled foods also rely on kōji.

Many Japanese breweries of sake and soy sauce and miso and pickle manufacturers cultivate their own kōji in-house, but they still need a source for the kōji mold they use to inoculate the cereal. Because great expertise is needed to maintain stable quality of this mold over many years, manufacturers rely on specialized seed kōji makers (known as moyashiya), of which just a few exist throughout Japan.

Sukeno Akihiko is president of Hishiroku, a long-established seed kōji maker. He shows us a historical document and explains: “This list from around 1953 includes thirty moyashiya, but now that number has fallen to just ten. We’re the only one left in Kyoto.”

Sukeno Akihiko, president of Hishiroku, explains the history of seed kōji makers. (© Kuroiwa Masakazu of 96-Box)

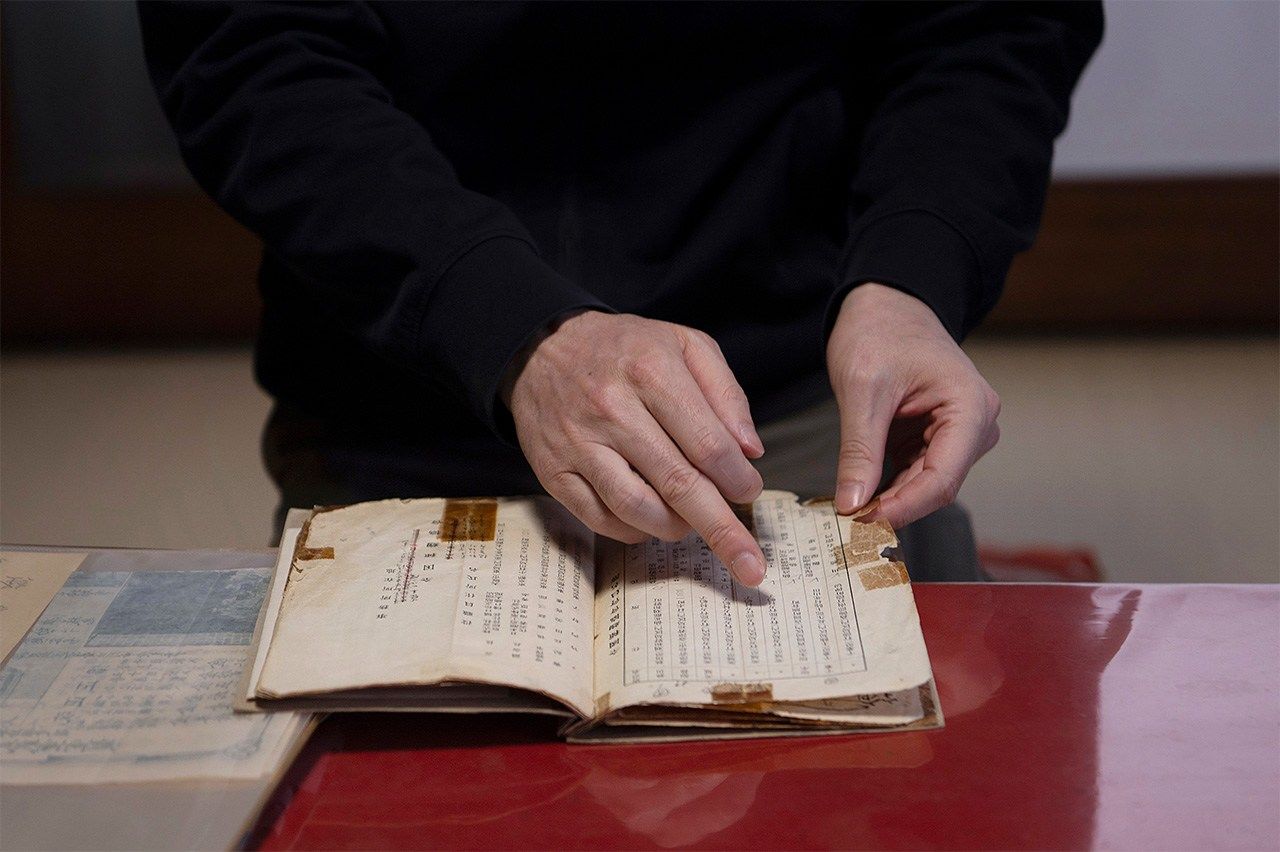

Sukeno carefully thumbs through the old list of makers in a document of the forerunner to today’s National Seed Kōji Association. (© Kuroiwa Masakazu of 96-Box)

“Some people confuse the term moyashi with the bean sprouts that use the same name,” says Sukeno. In fact, the base verb of the word, moyasu means “to sprout,” so the etymology is the same.

As a seed-kōji maker, Sukeno’s job is to encourage quality kōji mold spores to sprout, and to provide ideal conditions to nurture them, before processing them ready for use by breweries and other manufacturers.

The History of Seed Kōji Making

The use of kōji mold in brewing in Japan stretches back over 1,000 years. Records from the eighth century describe sake production using mold that grew on rice offerings to the gods.

The Engishiki, a compilation of laws and customs completed in 927, also mentions rice moyashi, referring to fuzzy mold growing on rice—known today as rice kōji. In those days, this was produced by a method known as tomo dane shiki, where part of the rice kōji is split off to seed a new batch. Even so, they were able to maintain a degree of purity.

In the Kamakura (1185–1333) and Muromachi (1333–1568) periods, an association of professional kōji makers, Kitano Kōji-za, was formed in Kyoto under the authority of the shrine Kitano Tenmangū to monopolize kōji production and sales rights in the region. But over time, a number of wealthy sake brewers began producing their own kōji.

This attracted strong opposition from the Kitano Kōji-za. Together with Kitano Tenmangū, they appealed to the shogunate to strengthen regulation of the sake brewers, a goal they achieved in 1419 when the government granted a kōji production monopoly to the group.

But Enryakuji, a powerful monastery on Mount Hiei, sided with the sake brewers, and the involvement of various complicated interests exacerbated the antagonism. After a series of armed conflicts, the Kitano Kōji-za was forced to submit to the brewers’ side in 1444, year 1 of the Bun’an era.

Following this so-called Bun’an Kōji Rebellion, the profession of dedicated kōji manufacturers declined, and the process was incorporated into the work of sake and miso production. Sukeno believes that, amid the course of these events, some kōji makers realized they could not survive just selling kōji, and began cultivating high quality kōji mold for wholesale to brewers.

Photo of the Hishiroku store, most-likely taken either in the Meiji (1868–1912) or Taishō (1912–26) era. The signboard (written right to left) bears the logo for Hishiroku, the description kōji-moyashi, and the word for “origin,” perhaps a reference to the role of kōji as the root of Japanese food culture. (Courtesy Sukeno Akihiko)

The shop still displays the old signboard, clearly showing the signs of 100 years of weathering. (© Kuroiwa Masakazu of 96-Box)

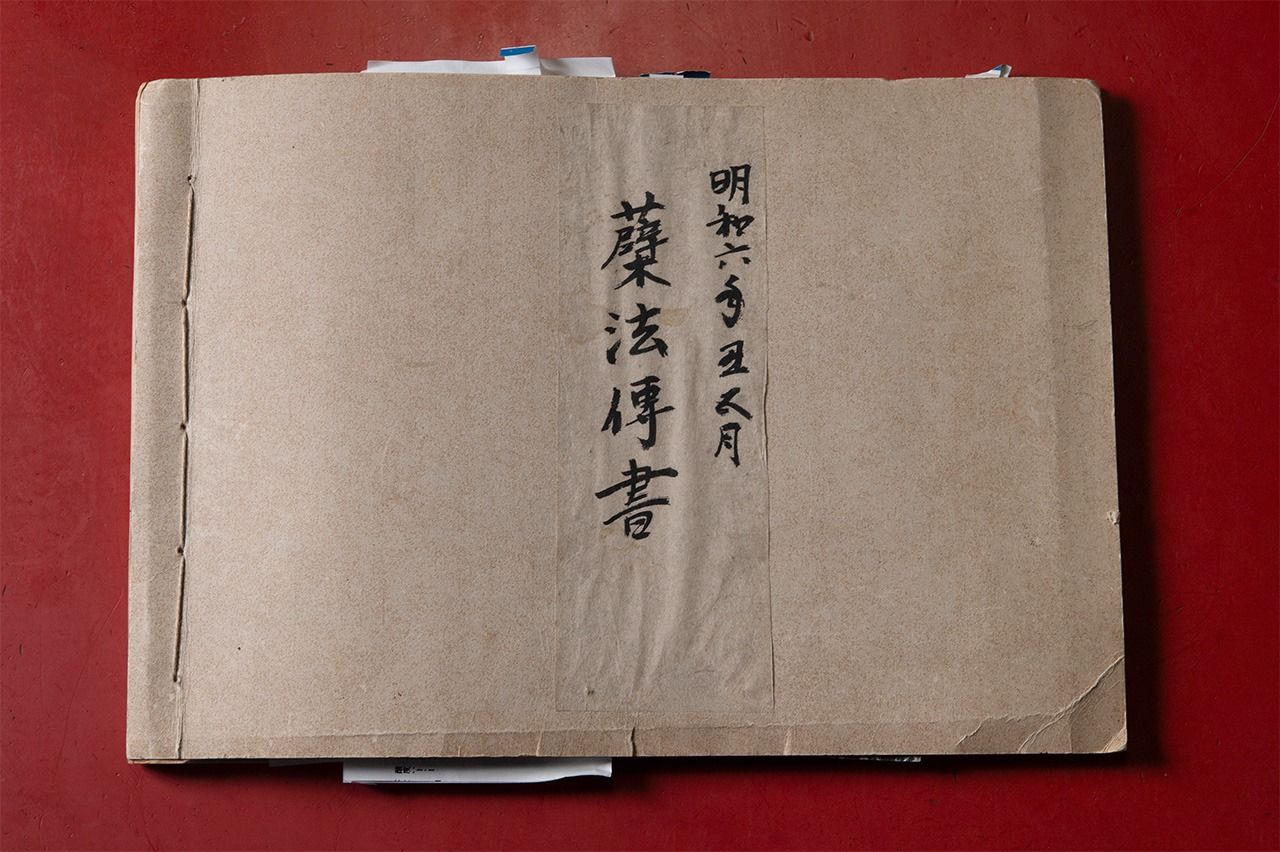

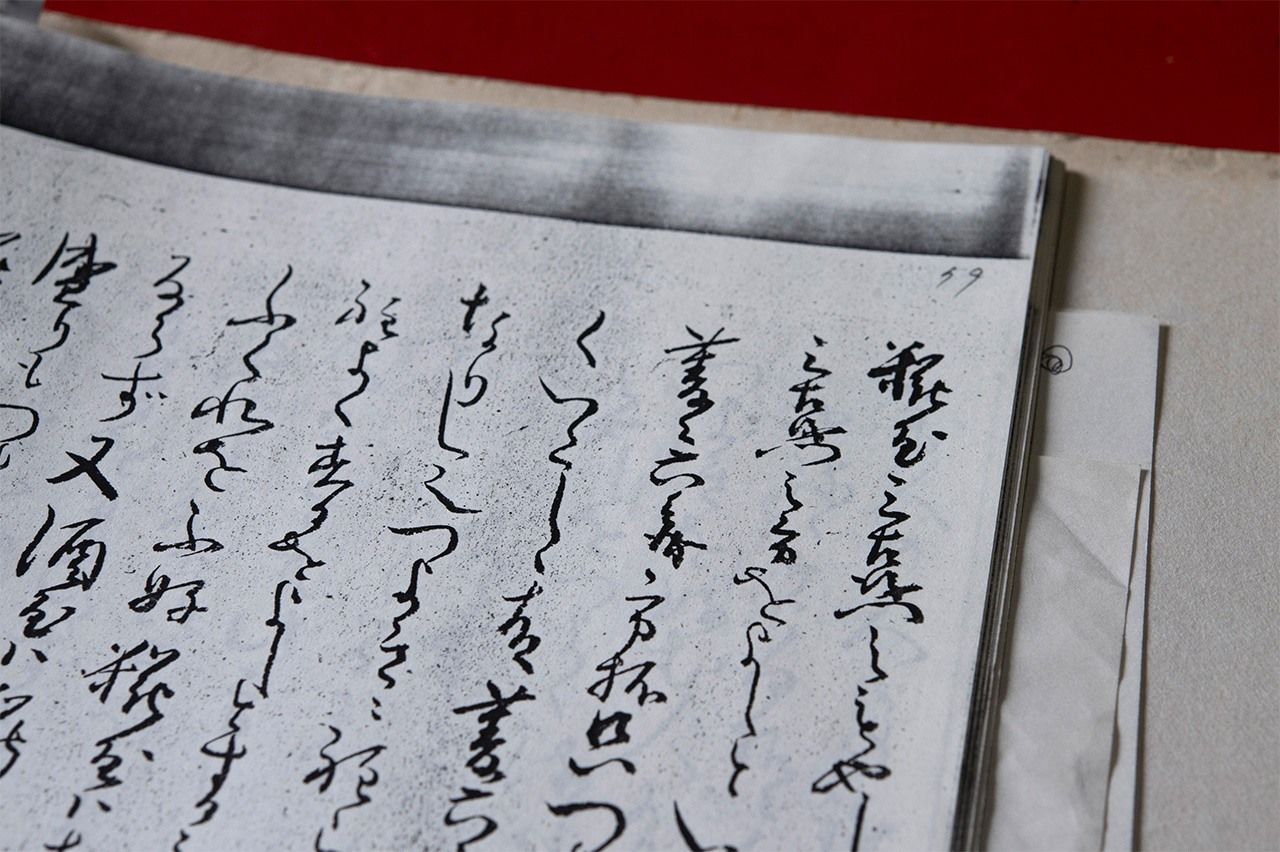

“We have been operating in Kyoto for a long time, but I’m not sure exactly when the company was founded. To be honest, I don’t even know my place in the lineage of ownership. This is a copy of a document from another seed kōji maker dating from 1769 that mentions Hishiroku, so at least I know we were operating at that time. I expect our business has existed for over 300 years.”

The copy of the document from 1769 in Sukeno’s safekeeping. (© Kuroiwa Masakazu of 96-Box)

The name “Hishiroku” is legible on the third line. (© Kuroiwa Masakazu of 96-Box)

The Process of Making Seed Kōji

The kōji mold that goes into Japanese foodstuffs represents a selection of the many members of this mold family that is actually useful to humans. Other types of kōji can be harmful. It can be hard to maintain the quality of the mold if kōji is seeded from an existing batch, using the aforementioned tomo dane shiki method.

This is where the seed kōji makers come in. They collect stable, high quality kōji mold, which they work hard to preserve and cultivate. Subsequently, they sprinkle this on steamed rice or other cereal, depending on the intended use, to breed stronger mold and to maximize the number of spores. It is a skill that requires years of experience and good intuition.

The area beyond the curtain is the kōji-muro, the room where the kōji is produced. (Courtesy Sukeno Akihiko)

Rice is cooked in a large drum-shaped steamer in preparation for the addition of the mold. (Courtesy Sukeno Akihiko)

Kōji mold is cultivated in the kōji-muro, which is kept at a temperature of 30°C and 98% humidity. (© Kuroiwa Masakazu of 96-Box)

The finished seed kōji. Dense growth of kōji mold spores is visible on the rice. (Courtesy Sukeno Akihiko)

Seed Kōji for Every Need

Seed kōji is actually a general term, but there are different colored variants depending on the specific mold used. The seed kōji generally used in sake and mirin brewing, and for some vinegar, is an olive color. Condiments such as miso, amazake, and shio-kōji are usually produced with a white seed kōji. Okinawa’s awamori liquor is made using a black variety, and shōchū with a light brown variety.

Seed kōji differs in color due to the different strains of mold used, chosen according to their intended application. (© Kuroiwa Masakazu of 96-Box)

Hishiroku sells seed kōji in two forms: grains of rice or other cereals that have been cultivated with kōji mold; and powder, which is sifted kōji with starch, rice flour, or other bulking agents added for easier use.

Green and white seed kōji in grain (left) and powder form. (Courtesy Sukeno Akihiko)

In grain form, it is hard to visually distinguish kōji from the seed kōji used to produce it. Hishiroku controls its kōji mold such that the spores have a sprouting rate of 95% or more, making it ideal for seeding kōji. After the seed is applied to the cereal base, the “child” kōji is cultivated for just 48 hours, less than half the time taken to make the “parent” seed kōji.

Hishiroku sells packs containing single strains of mold, as well as blends. Sukeno also consults with his clients each year and makes minor adjustments to the seed kōji as needed.

A selection of Hishiroku’s products. (© Kuroiwa Masakazu of 96-Box)

The Future of the Industry

Hishiroku’s sales were limited to the Kyoto area in the Edo period (1603–1868), but have expanded nationwide with the decreasing number of seed kōji makers and improved distribution technology. Currently, it boasts some 2,000 clients. The company has few competitors, and in an industry where tradition itself is considered part of the product, there is little opportunity for newcomers. In fact, because it is possible to make 100–200 kilograms of kōji from just 100 grams of seed kōji, it seems like a shaky basis for a profitable business.

It might also seem to suggest that the seed kōji industry will continue to decline. The survival of these makers is intimately linked to Japan’s food culture, which relies on kōji. Is washoku itself at risk? Sukeno is surprisingly light-hearted about such doubts: “While the industry is waning somewhat, I’m not particularly concerned.”

Sukeno believes efforts to raise awareness about kōji are paying off. (© Kuroiwa Masakazu of 96-Box)

Over the last 15 years, there has been a boom in the use of shio-kōji in home cooking for marinating and as a salt substitute, and more people are drinking kōji-amazake for its health benefits. According to Sukeno, this has led to greater interest in kōji among regular consumers, and a noticeable increase in awareness. He receives more requests for interviews from the media, and when he is invited to give lectures about seed kōji, they always attract a large audience.

When Hishiroku held a three-day workshop on making kōji from seed, it was booked out. “Frankly, I was surprised there was so much demand. In fact, you can buy kōji at the supermarket, which is quicker than making it. It’s encouraging—I’m grateful that so many people are becoming interested in this mold.”

Kōji Culture Spreads Globally

Business inquiries from outside Japan have also been increasing over the past decade. “Some tourists from overseas take the trouble of visiting our store, saying they saw us online. We’ve also started shipping abroad, following inquiries through our online shop from miso manufacturers, restaurants, and individual customers, including Japanese people living overseas. The number of countries we export to is constantly growing: The United States, Germany, France, Denmark, the Netherlands . . . We’ve even had inquiries from Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries.”

Some tourists have been attracted to the shop due to its charming exterior. (© Kuroiwa Masakazu of 96-Box)

One wonders if exporting seed kōji would be considered as leaking biotechnology overseas. For example, a customer overseas might try using purchased kōji mold to cultivate it themselves. According to Sukeno, “We ask what they intend to use it for, and decline the request if it’s for research.” In reality, no matter how much care is taken with temperature and humidity control, it is hard to continue harvesting kōji mold of consistent quality without extensive experience.

There is no concern for the survival of Hishiroku’s seed kōji, handed down over generations. Because the mold is a living organism, a subculture must be produced every few years. This is laboratory tested to ensure the quality is not diminished, and is safely stored in two locations. Seed kōji manufacturing is a profession with both history and significance, but when speaking with Sukeno about future prospects, he does not appear anxious.

He sounds upbeat, explaining that “we’ve finally reached the stage where people are aware of kōji, but it will still be some time before people understand the role of seed kōji in its production.”

Kōji has quietly developed the palates of Japanese people and food culture for over 1,000 years. Behind the scenes, unknown to most people, moyashiya have protected these traditions that underpin Japanese cuisine.

Sukeno stands by the curtain at his store’s entrance, which bears the Hishiroku logo. (© Kuroiwa Masakazu of 96-Box)

Hishiroku

- Address: 79, Rokuro-chō 2-chōme, Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto

- Tel.: 075-541-4141

- Web: https://1469.stores.jp/

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Signboard of Hishiroku, a seed kōji store with over 300 years of history. © Kuroiwa Masakazu of 96-Box.)