Nagasaki Sites Associated with Endō Shūsaku’s “Silence”

“A Life of Jesus”: Scorsese Adaptation Shines New Light on Endō Shūsaku Novel

Books Cinema Culture History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

No Miracles

In January, a Los Angeles Times article announced that Martin Scorsese would make a film of Endō Shūsaku’s A Life of Jesus. The columnist Glenn Whipp reported how Scorsese said that he had told Pope Francis his intention in a 2023 meeting, and while the director said he was still “swimming in inspiration,” the screenplay was already complete, with shooting planned for later in the year.

Endo’s A Life of Jesus was published in 1973, seven years after his Silence, which told the story of Portuguese Jesuit missionaries in seventeenth-century Japan, and was previously adapted by Scorsese in 2016. Endō discusses his beliefs in the later collection of speeches Jinsei no fumie—the title could be translated as Life’s Fumie, with fumie referring to the Christian images suspected Christians were made to trample in Japan to show that they were not believers.

In Silence, I decided that rather than taking the perspective of the strong that “you mustn’t abandon your beliefs even if persecuted,” I wanted to write from the viewpoint of a weakling like me. If the weak, like the strong, have meaning in their life, what is it? This is one of the major themes of Silence. The strong and the weak also became an important theme after this book. While I respect the strong, because I can’t become one of them, I’ve always empathized with the weak. And I’ve considered how the strong were able to gain their strength and whether being a weakling is an inherent characteristic since birth.

Endō writes in the piece that he had read the Bible thousands of times, but there were many parts where he was unable to connect with it. After he finished writing Silence, he reread the holy text—seeing the central figures as people like him (i.e., weaklings)—as a book that presented how the weak became strong, and thereby came to feel a sense of connection.

While, as the title suggests, A Life of Jesus is a biography of Christ, Endō’s Jesus performs no miracles. He presents a figure that is neither heroic nor beautiful. Instead, he is a powerless, lonely man who earns the disappointment, anger, and ridicule of the people, and is misunderstood and abandoned even by his disciples. Even so, he chooses to be executed upon the cross, bearing everyone’s suffering as an “eternal companion,” like a mother who attempts to share her children’s sorrow and pain, weeping together with them.

If Jesus is strong, the disciples are weak. After Jesus is caught, they scatter in all directions, terrified that they will be killed if it was learned that they were his followers. Here there is a parallel with how Japanese believers were made to trample fumie on the threat of death in the Edo period (1603–1868). However, the same piece by Endō includes the following passage.

The most interesting aspect of the Bible to me is how the weakling disciples gathered again, speaking of Jesus, who they betrayed, and spreading his teachings before dying at the hands of persecutors. In other words, the weak became strong. How did this happen?

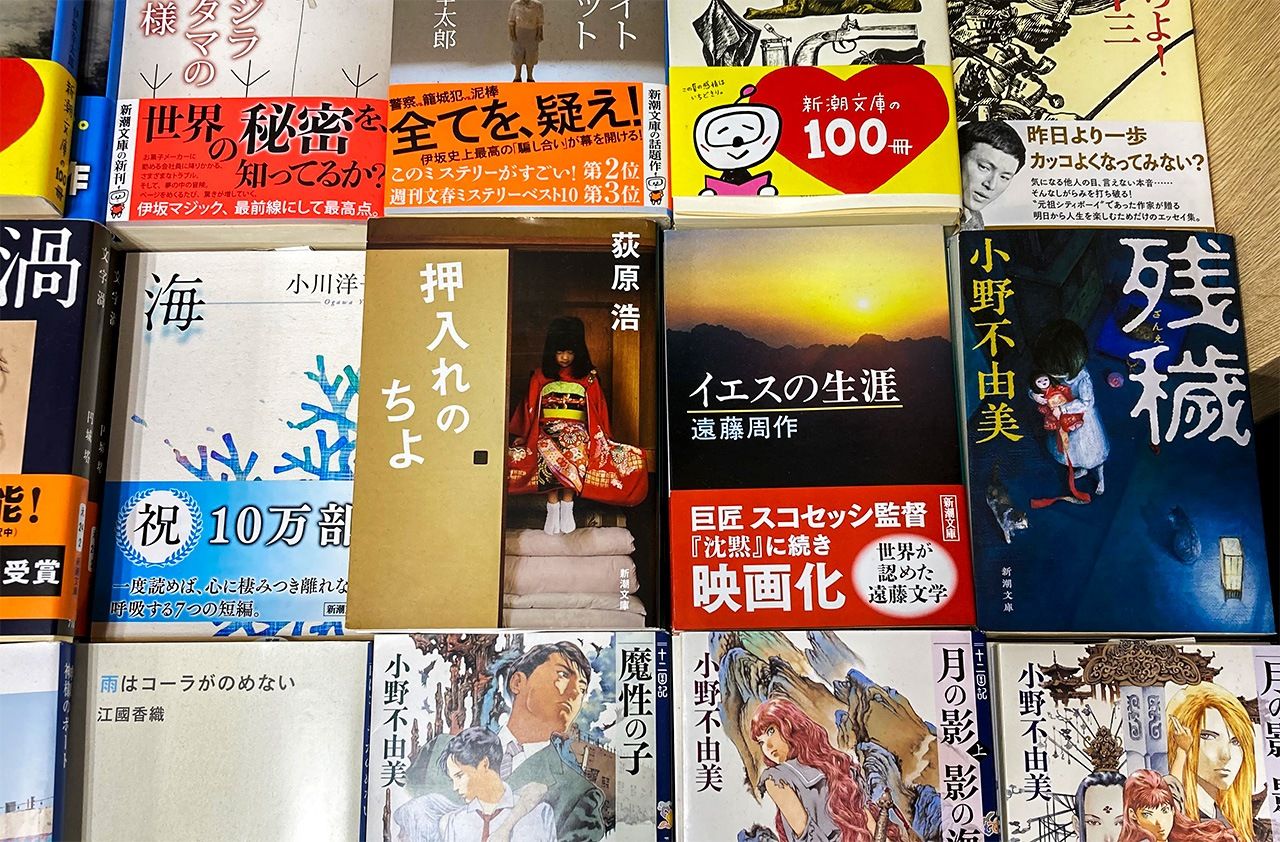

A Life of Jesus has come under the spotlight again in Japan since the news broke that Martin Scorsese will adapt it. In a Tokyo bookstore, the book (center right) highlights this news on a red obi strip. (© Amano Hisaki)

Making Jesus’s Teachings More Accessible

In A Life of Jesus, Endō says that he set himself the task of creating a concrete image of Jesus that could move readers with no connection to Christianity. While building on earlier accounts of his life, the writer used his imagination, respecting episodes thought to be invented, as he saw them as containing hidden truths.

How will Scorsese adapt Endō’s unique view of the Bible? He imagines it as set mostly in the present day, but wants it to be timeless, without being locked into a particular period, and is seeking a fresh perspective on Jesus’s core teachings. “I’m trying to find a new way to make it more accessible and take away the negative onus of what has been associated with organized religion,” he says. Israel, Italy, and Egypt are among the potential shooting locations.

Scorsese shares his thoughts on religion in the Los Angeles Times interview: “Right now, ‘religion,’ you say that word and everyone is up in arms because it’s failed in so many ways. But that doesn’t mean necessarily that the initial impulse was wrong. Let’s get back. Let’s just think about it. You may reject it. But it might make a difference in how you live your life—even in rejecting it. Don’t dismiss it offhand.”

When a delay to the start of filming was announced in October, speculation swirled that Scorsese would retire, but he dismissed such talk. “I still have more films to make, and I hope God gives me the strength to make them.”

Martin Scorsese (center) with his daughter Francesca (left) at a film festival in Turin on October 7, 2024. (© Marco Destefanis IPA/Sipa USA via Reuters Connect)

Hidden Christian Villages

Scorsese grew up in Little Italy, New York, and all his grandparents were Sicilian immigrants. His upbringing in this Mafia-controlled area had a strong influence on his work, which depicts characters struggling amid the corruption of society and the contradictions of life.

Endō Shūsaku’s son Ryūnosuke, who is vice chairman of Fuji Television and chairs the Japan Commercial Broadcasters Association, is looking forward to Scorsese’s adaptation. “Dad’s novels are all about the weak and marginalized, particularly Kichijirō in Silence, and so are Scorsese’s films. I feel their styles are similar in a way. I hope The Life of Jesus will be a major addition to his filmography.”

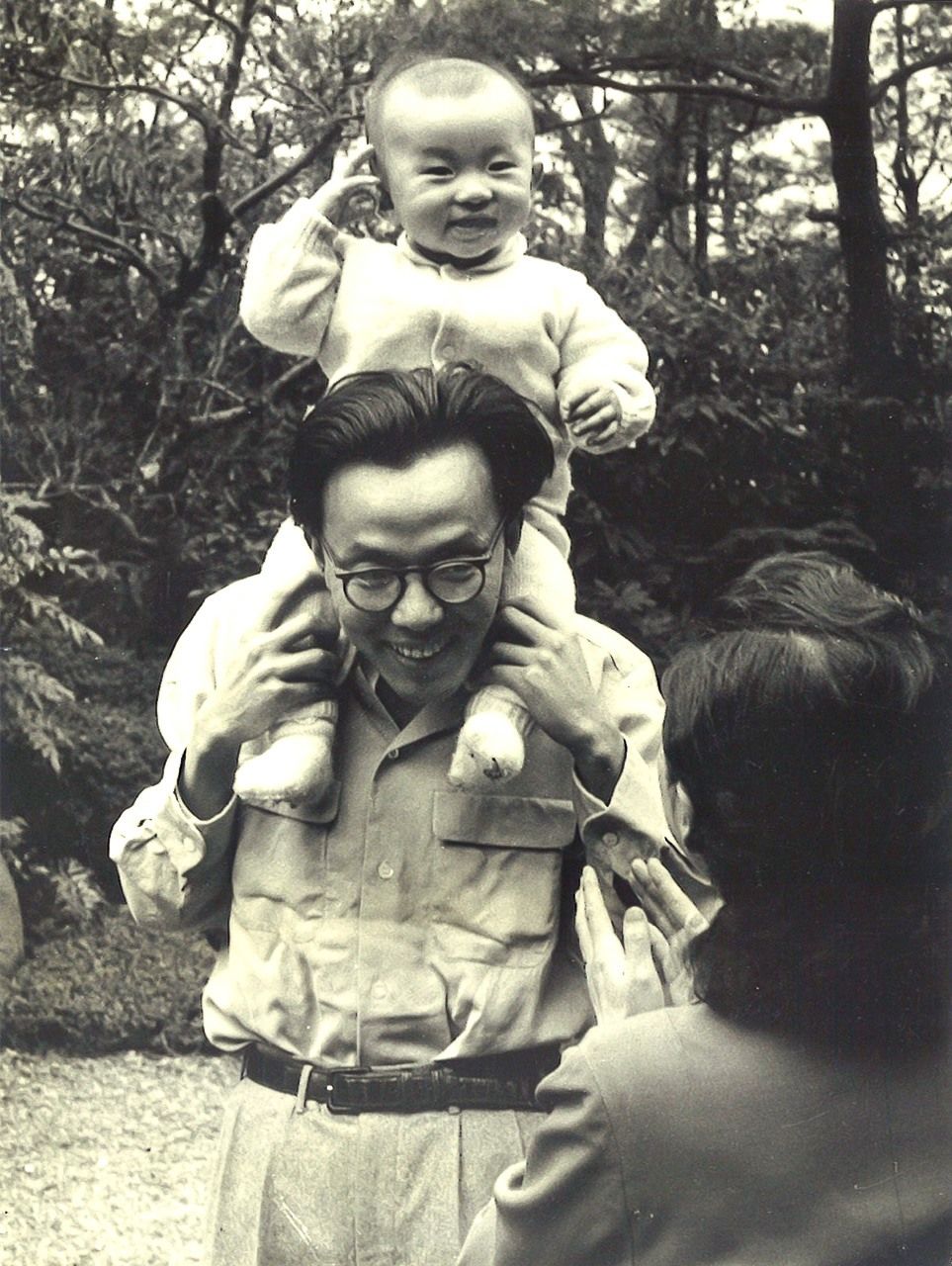

Silence is associated with some unforgettable memories for Ryūnosuke, as he took time off school to accompany his father on a research trip to Nagasaki. “I must have been about ten, when Dad suddenly told me, ‘I’m going to Nagasaki for five days from next week to do some research for a new novel, so I want you to come with me. You’ll learn much more than you would in school.’”

Ryūnosuke says he was excited by the prospect of flying in an airplane and enjoying some tasty food, but the trip turned out differently than how he had expected. They traveled with an editor from the publishing company and someone involved with the Nagasaki Christian community. On the day they arrived, they did some light sightseeing and ate local specialties, but from the following day they sped around the area in a hired vehicle to locations like Hirado and the Gotō Islands, visiting villages of hidden Christians, who had concealed their faith during the Edo period.

Once his father and the others entered a home, they would not emerge until about two hours later. While this happened again and again, Ryūnosuke waited in the car with the driver. He got hungry, and as darkness fell, he was close to tears. Unable to bear it any more, one night, he demanded, “I spend every day in the car, so I don’t know what I’m learning.” His father snapped back, “I’m the one who brought you here, so if you don’t understand my feelings, go back to Tokyo right now!”

“Now I look back on it, I don’t think there was anything especially wrong in what I said,” Ryūnosuke comments. “But the way I said it was wrong. Probably this isn’t only the case in my family, but writers deal with words for a living, so they’re highly sensitive to what others say to them, even if they’re family members.”

Endō Ryūnosuke on his father’s shoulders. (© Endō Shūsaku Literary Museum)

Mischief Maker

Ryūnosuke says that his father also had a love of mischief and a strong sense of humor. He remembers a particular episode when he was still in junior high school. A Ginza businessman friend and his wife were due to go to Europe for their silver wedding anniversary. He hated airplanes and had never traveled overseas, but his wife was set on visiting Paris. The couple went to Endō’s house before their departure to ask his advice.

“Dad’s face lit up, as he told them, ‘Here are two things to look out for,’” Ryūnosuke explains. “When you get on the plane, first you need to give tips to the stewardesses. They’ll look after you through a long journey, so give all of them about ¥5,000 each. Prepare some envelopes for that in advance. Another thing is the International Date Line. About two hours after you leave Haneda, a long red line made of plastic will appear on top of the ocean, and the plane will descend here, so make sure to have a look.”

The two diligently noted down Endō’s advice. It turned out that they put big smiles on the airplane staff members’ faces, and received excellent service throughout the trip.

Endō’s sense of humor also targeted family members. In his late teens, Ryūnosuke found a girlfriend who called him at home. As a writer, Endō spent most of his time in his study, and was usually first to the telephone. “He’d pick up the phone, and say, ‘You must be the girl who went on an overnight trip with my son last week.’ That was a lie, so she’d say, ‘I’m not,’ and hang up. The next day, I’d hear the whole story from her at school.”

Once, he protested about his father getting in the way of his love life, and Endō responded with a straight face. “Do you know the French author Marcel Proust? He said that steadiness kills passion, while insecurity heightens it. I’m adding some spice to your relationship for you.”

Nobody Purely Good or Bad

Endō switched easily between his serious and humorous side in life. In his writing career too, as well as creating literary novels like Silence, he produced comic works based around a persona called Korian. Ryūnosuke says that his father believed that people have various sides to their character, and that it is not possible to simply divide them into those who are good and those who are bad—there is nobody purely good or bad.

“The question is how to come to terms with your own useless or weak aspects, or to turn them into something positive. You need another self to look at you objectively. I feel this is what Dad taught me.”

Endō Ryūnosuke says that “I feel like more than half of my values come from my father.” (© Amano Hisaki)

However, the world seems to be going in the other direction with an escalation in intolerance over the past few years. “It’s strange to say this when I’m part of the media,” Ryūnosuke goes on, “But recently the media will castigate someone for showing the least sign of weakness. Without caring at all about that person losing their position in society. When commentators make their solemn proclamations, I want to ask them, ‘Are you God? Are you all-powerful?’ I think we’ve come to a point where the media needs a period of reflection, including my TV network.”

Ryūnosuke adds, “I sometimes wonder what Dad would have to say about this tendency, if he was alive now. I will be happy if Scorsese’s adaptation of A Life of Jesus catches the attention of lots of young people around the world, and can make them love with simple honesty, and sense the importance of giving a thought to others’ feelings.”

- Works in English translation mentioned in the text: Iesu no shōgai (A Life of Jesus), translated by Richard J. Schuchert; Chinmoku (Silence), translated by William Johnston.

(Originally published in Japanese on November 6, 2024. Banner photo: Martin Scorsese, at center, meets Pope Francis, at left, in the Vatican. © IPA/ABACA via Reuters Connect.)

Related Tags

Christianity Endo Shusaku Martin Scorsese Japanese language and literature Jesus Christ