Nagasaki Sites Associated with Endō Shūsaku’s “Silence”

The Hidden Christians of Ikitsukishima: Japanese Islanders Who Kept the Faith

History Culture Society Travel Guide to Japan- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The remote island of Ikitsuki in Nagasaki Prefecture was home to generations of so-called hidden Christians. These faithful concealed their beliefs during the long period of persecution that existed in Japan for most of the Edo period (1603–1868). Traces of their stories remain, but getting to Ikitsuki to hear them is no easy task. Starting my journey at Nagasaki Station at six thirty in the morning, I take a series of buses that eventually deposit me at my destination, the Shima no Yakata Museum, shortly before noon.

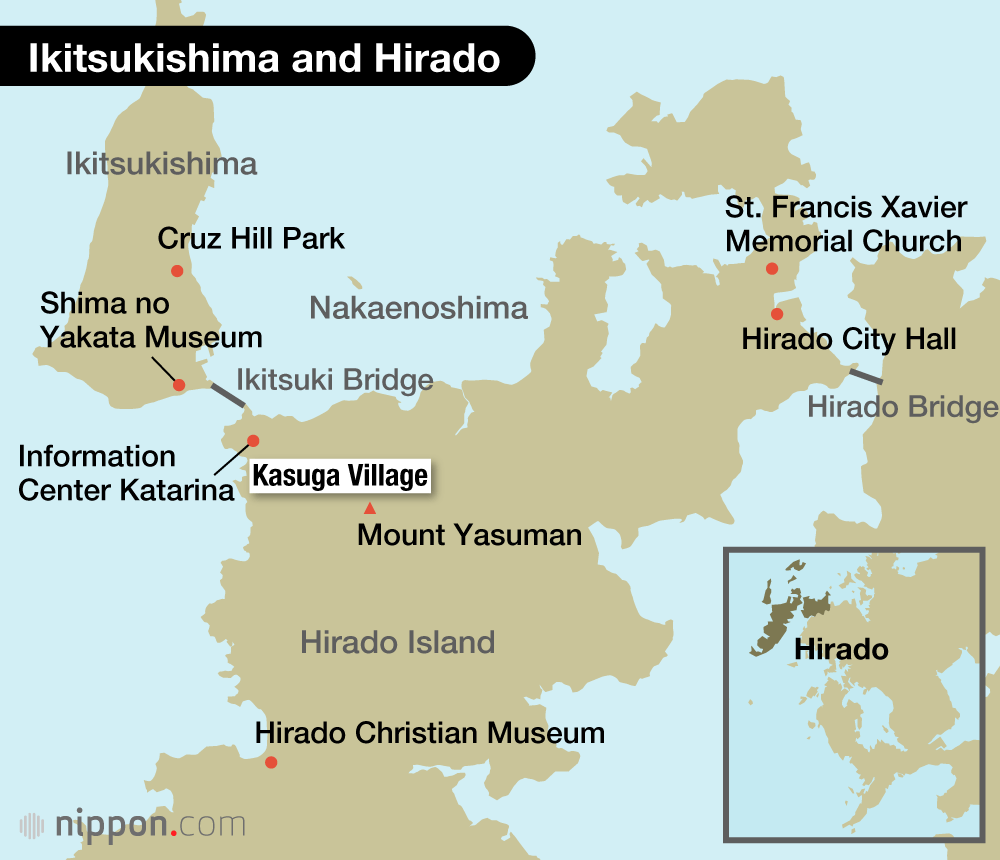

Ikitsuki Bridge connects the islands of Hirado and Ikitsuki. (© Amano Hisaki)

“Old Christians”

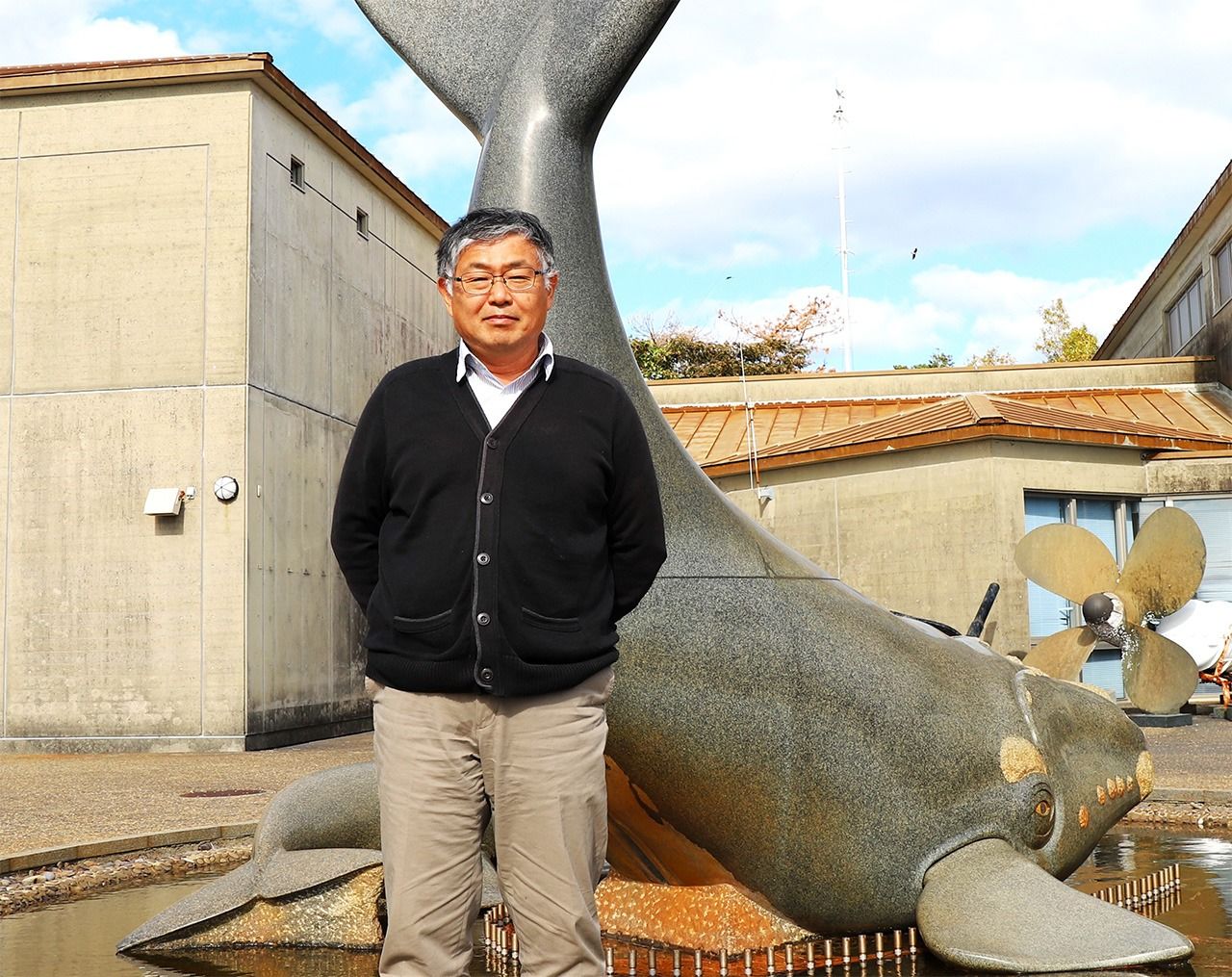

Nakazono Shigeo, the museum director, has studied hidden Christians for 30 years, including conducting numerous interviews with residents of Ikitsuki. I ask him about the many different names for the people of this faith.

Senpuku kirishitan is used for those historical “hidden Christians” who registered as parishioners of Buddhism temples or Shintō shrines during the period when Christianity was banned but practiced their faith in secret. After the prohibition was lifted in 1873, those who were then formally baptized are known as Catholics, but people who continued to practice the hidden version of Christianity became known as kakure kirishitan.

“On Ikitsuki, believers don’t have a particular name for their faith, but if there’s a need to distinguish from today’s Catholics, they might describe them as ‘new Christians,’ and call themselves ‘old Christians,’” Nakazono explains. He notes that kakure, meaning “hidden,” is written in different ways depending on the researcher. Those who use the kanji 隠れ emphasize the clandestine nature of the faith, while the katakana カクレ has the nuance that there is no longer a need to hide. Nakazono himself uses the hiragana かくれ, which represents a middle ground between the two.

Shima no Yakata Museum Director Nakazono Shigeo has researched the history of the hidden Christians as well as the island’s whaling tradition, which are both focuses of the museum. (© Amano Hisaki)

Prayers Passed Down

There are four settlements where the faith has endured on Ikitsuki: Ichibu, Sakaime, Motofure, and Yamada. In Ichibu I observe three members of the village perform orasho, prayer chants kakure kirishitan sing in various ceremonies and rituals through the year. The word derives from oratio, Latin or Portuguese prayers that arrived in Japan in the sixteenth century.

The men chant a series of around 30 orasho over 30 minutes, sometimes with their palms together and sometimes making the sign of the cross. They finish with three sung prayers: “Raodate” (Laudate Dominum), “Najō” (Nunc dimittis), and “Gururiyōza” (O Gloriosa Domina). This cultural practice remains only in Ikitsuki and is believed to be the first Western music brought to Japan.

Three kakure kirishitan chant orasho. (© Amano Hisaki)

“’Gururiyōza’ was originally sung in the sixteenth century on the Iberian Peninsula,” Nakazono explains. “It was replaced by other kinds of Gregorian chants that arrived from Italy, but the tradition continues today on Ikitsuki.”

A study by musicologist Minagawa Tatsuo found that a chant in a score published in Spain in 1553 had the same Latin lyrics and tune as “Gururiyōza.”

“Gururiyōza”

Gururiyōza dōmino, ikisensa sunderashīdera

Kiteya kiyanbegurūride, radasude sākuraōberi

“O gloriosa Domina”

O gloriosa Domina, excelsa super sidera,

qui te creavit, provide, lactasti sacro ubere.

(O Heaven’s glorious mistress, enthron’d above the starry sky!

thou feedest with thy sacred breast thy own Creator, Lord most high.

Translation by R. F. Littledale and others.)

“Some researchers say that as believers didn’t write their orasho copies using characters that conveyed the meaning of the original prayers, they were greatly transformed and don’t reflect the original religious doctrine,” Nakazono says. “But orasho are basically not for transmitting doctrine, but for conveying individuals’ feelings to God, so it’s more important to use the original words.”

Even today, the words used in prayer chants on Ikitsuki are roughly the same as when they first came to Japan. The prayers used by Japanese Catholics, on the other hand, have changed significantly.

Preserving Form

Many books and researchers have noted how the faith of the hidden Christians transformed with the disappearance of missionaries from the country due to the ban on Christianity. The 1988 work Nihon shūkyō jiten (An Encyclopedia of Japanese Religion) by Murakami Shigeyoshi includes the following description.

The decree prohibiting Christianity meant that the hidden Christians were completely cut off from the teachings of the Church, and could only pass on doctrine and observances in isolation over a long period. This meant that they gradually became more distant from the original Catholic doctrine and observances, while deepening syncretism with long-standing community religions.

As “Gururiyōza” shows, however, many practices continue to be observed by kakure kirishitan, which Nakazono says is true not only for the orasho but also agricultural rituals and other aspects. “Contrary to common opinion, the absence of the missionaries meant that believers didn’t know what to change or how to do so and faithfully passed down what they had learned in the same form. The kakure kirishitan elders say this themselves.”

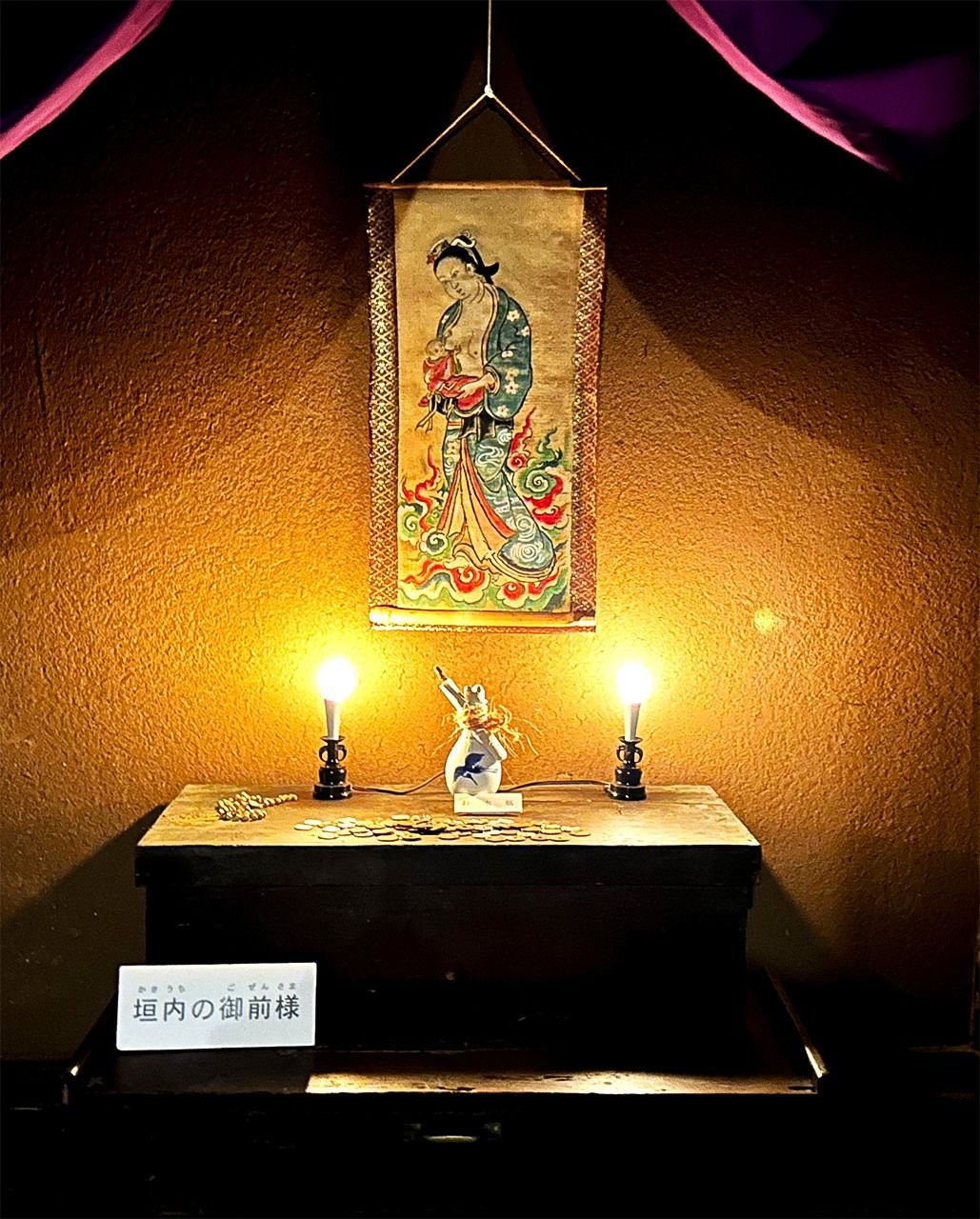

In the homes of kakure kirishitan on Ikitsuki, there are many objects of worship, such as picture scrolls, Buddhist altars for ancestors, and charms from local Shintō shrines. Instead of mixing with other religions, Christianity stands alongside Buddhism and Shintō.

Sacred picture scrolls are important religious objects for the kakure kirishitan of Ikitsuki. They are thought to have been produced at a seminary workshop around the 1590s and distributed to believers. Motifs include Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary and child, and John the Baptist. (Courtesy Shima no Yakata Museum)

There are altars in each of the kakure kirishitan settlements on Ikitsuki for displaying picture scrolls. (Courtesy Shima no Yakata Museum)

An otenpensha is a sacred object formed by tying many small ropes together. It was used in purification rituals and to drive the “bad airs” that cause illness from an ill person. (Courtesy Shima no Yakata Museum)

In the mid-sixteenth century, Koteda Yasutsune, who controlled Ikitsuki and the west of Hirado, forced residents to convert to Christianity. Buddhist temples became churches and their statues were removed and burned. His Catholicism did not allow coexistence with other religions or faiths. This starkly contrasts with how the villagers of Ikitsuki maintained Christianity, Buddhism, and Shintō alongside each other.

In the era of prohibition, the shogunate cracked down hardest on territory belonging to Christian daimyō. However, the Hirado domain had enforced its own crackdowns some time earlier, and thereby avoided the scrutiny other areas received. Ikitsuki and Hirado were also relatively distant and open to other cultures. These factors meant that it was easier for residents to maintain their Christian faith, and almost none formally returned to the Catholic church after the ban was lifted.

St. Francis Xavier Memorial Church and nearby Buddhist temples in Hirado. (© Amano Hisaki)

A Record for the Future

Interest in kakure kirishitan has grown since the registration of the Hidden Christian Sites in the Nagasaki Region as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2018. However, their faith faces an uncertain future.

Nakazono says, “After the ban on Christianity was lifted almost the whole of Ikitsuki continued as kakure kirishitan rather than join the Catholic church. Records show that just under 90 percent of the 11,000 residents were believers in 1954. But in 2017, there were less than 300, and that number seems to have dropped further to below 200 now.”

Tanimoto Masatsugu, one of the four orasho performers, laments the difficulty of finding people to carry on the tradition. At 67, he is the youngest of the group, whose other members are all in their seventies. “When we tried finding successors by asking the young people,” he says, “nobody was interested. We only chant a few times a year now, at memorial services.”

When he was a schoolboy, he recalls that there were many adults who performed orasho on occasions like New Year or the autumn harvest festival. At such gatherings, women would spend long hours preparing food, but the rigors of holding these events have seen them slowly fade away.

This spring, Nakazono began digitizing around 400 video tapes taken from 1995 onward in an attempt to preserve traditions. “The kakure kirishitan faith may die out one day. I have to record its cultural forms to teach future generations and the world. That’s why this museum was built.”

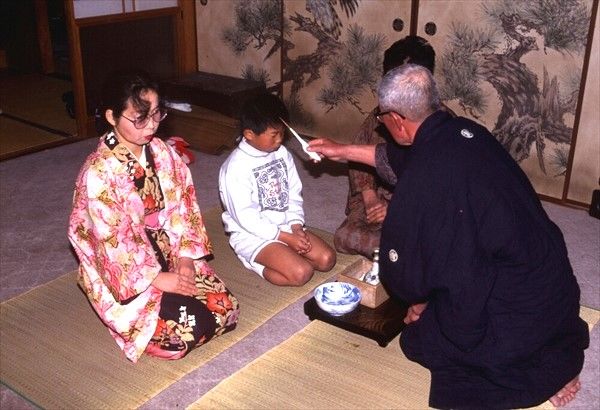

Baptism have not been practiced on the island for nearly three decades. (Courtesy Shima no Yakata Museum)

Sharing Memories

Just across Ikitsuki Bridge on the west coast of Hirado, the village of Kasuga is a popular tourist spot that is part of the Hidden Christian Sites in the Nagasaki Region. Despite the ban on Christianity, residents followed the faith alongside the ancient tradition of mountain worship centered on the local peak of Mount Yasuman. They did not become Catholics when freedom of religion was restored, choosing instead to continue as kakure kirishitan. Subsequently, there are no churches in the village.

The organized faith of the kakure kirishitan no longer exists in the settlement, with its last event taking place in 1998. However, at Information Center Katarina, opened in April 2018, local residents go every day to share their history with visitors over tea, snacks, and homemade pickles.

Information Center Katarina is a renovated folk house with one building for an exhibition and shop, and the other for meeting local residents. (© Amano Hisaki)

Yamaguchi Mitsuko says she tells visitors about free diving for tengusa seaweed, abalone, and sea urchins. (© Amano Hisaki)

The name Katarina combines Japanese based on the concept of making connections through storytelling and local dialect, meaning “to take part in activities.” It conveys the commitment of residents to share the cultural faith of their ancestors.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Terraced rice fields in the village of Kasuga. © Pixta.)