Absenteeism: Solutions Meeting a Need

Education Family Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Project Called “School”

Every Monday, members of a mini-school get together at the YCC Yoyogi-Hachiman community center in Tokyo’s Shibuya. In the center’s large tatami-floored room, seven adults and children gather around a round table to discuss organizing a “children’s lunch room” charity project that will take place in some weeks’ time. They talk about menu choices, pricing, how many meals to prepare, and who will be in charge of serving, taking orders, and handling payment. “Hey, I think I’ve got it,” says 10-year-old Kei, skillfully manipulating an iPad to draw an illustration of the menu of tonjiru pork and vegetable stew and onigiri rice balls. Using their own tablets and laptop computers, the other children join in to offer their opinions.

Creating a menu using the free design tool software Canva. (© Power News)

That describes what goes on at the Project for Everybody School, an alternative learning program set up in February 2023 by parents to help children who have difficulty attending regular school. Participating were three children in third through fifth grade and their guardians, along with other adults supporting the endeavor. Every month, the children plan and implement a different project.

Last year’s project was a children’s booth at a community festival in May. The children avidly discussed the details, for example, the distance to the target in a shooting game, how many shots to allow per play, and how much to charge for the game, acting out the various moves as they talked.

During the summer holiday, the children entered a video contest for elementary and junior high school students. 11-year-old Fumi, who tore through six novels and eight manga in one day, and whose favorite is Sangetsuki, a short novel by Nakajima Atsushi set in eighth-century China, was the scriptwriter.

At Christmas celebrations in December, the children dressed up as Santas and delivered presents to a children’s home in the city. In the early days of the program, Kei and Fumi had visited the home to ask the children for their “wish list” and had painstakingly saved up money earned from the children’s festival booth and other sources to buy presents.

Children in Santa Claus suits delivering presents. (Courtesy Project for Everybody School)

After the weekly meeting comes play time. The children race around the spacious room, playing adventure games or putting on impromptu skits. Adults from various backgrounds often join in. Kei remarks that “Here, we can do things that we can’t at school. Once we’re done with one project, it’s fun to start on another one.”

Play time after a meeting. Ten (left rear), the children’s favorite play worker, joined in the fun. (© Power News)

The impetus for the Project for Everybody School came about when Kei stopped attending school in second grade. His mother, Nakahara Mari, describes Kei as “a sensitive soul from an early age, who would feel hurt when he saw his friends being scolded.” Although Kei could read well, he found writing a challenge, and would be upset at not being to write in class, even though he knew the answers during lessons. When a male teacher was put in charge of his class, Kei started being afraid to go to school. In third grade, he was able to attend school for about six months, but the issue resurfaced in fourth grade. Mari says that Kei liked school and his friends, but that he was not comfortable in a large group; regular school just was not the right framework for him. On days when Kei could face going to school, Mari would accompany him, but she began thinking of other possible options.

No Need to Force It

Another child, Kawai Kanon, attending a different school, began having difficulties around the same time. Her mother, Mami, recalls her daughter’s first grade teacher telling her in the first few months of the school year: “Kanon goes to the toilet ten times a day; it’s very disruptive for the class.” When school resumed after the summer holiday, Kanon would start hyperventilating when she got near her classroom. She moved her desk to the hallway to listen in on the lessons. When that became too much, she moved to a nearby empty classroom and spent the hours doing drills on paper with her mother. Then COVID-19 came along, curtailing use of the empty classroom. Mother and daughter tried to find a suitable spot in the school building but ultimately ended up passing the time in the schoolyard.

“At the time, all I could think of was that Kanon ‘had’ to attend school. I felt so awful that there we were, the two of us in the schoolyard, when her classmates were attending lessons inside.” Kanon’s condition worsened; she could not sleep at night, and her legs progressively weakened, leaving her unable to stand. Mother and daughter made the rounds of various doctors to try to pinpoint the problem. Finally, on a visit with a fourth doctor, they met with a child psychologist who told Mami that “If Kanon finds going to school so difficult, then she needn’t feel she has to attend. Find her something that suits her better.” With those words, Mami felt that her concerns were finally being heard.

Mami recalled how in kindergarten, Kanon had been a lively child, adept at gymnastics. One day when they were in the park, Kanon apologized for not being able to attend school. Mami reassured her that Kanon being healthy was enough for her, but she found herself wondering how she could help her daughter.

The mothers of Kei and Kanon encountered other parents in similar straits at the small number of “free schools” in Tokyo catering to younger schoolchildren, where they shared their experiences. Even though their children were unable to face regular school, they wanted to learn, and to meet and play with other children. The parents wondered where they could find an alternative educational setting. Kamizono Machiko, a Shibuya city council member who takes an interest in education, advised them that going through regular bureaucratic channels for a solution would take time and have only limited effectiveness. Kamizono offered her support and suggested that the mothers set something up themselves.

First Anniversary Celebration

That was the lightbulb moment for Mami—she herself could create a safe space for her daughter and other children in need of support. Even if their children only got together to play, the occasion would also be an opportunity for the mothers to talk about their feelings of isolation. Mami and the other mothers decided that the group would meet on Mondays, a day when children ambivalent about attending school often tend to stay away. Mami posted a message on social media, the gist of which was that she wished to create a welcoming space for children who, either because of learning difficulties or for other reasons, did not fit in at regular schools, and was looking for volunteers to support the endeavor.

Several days later, a positive response came from Kondō Miwa, a part-time special education teacher. Originally an English teacher at an integrated junior and senior high school, she had switched to special education after developing an interest in the use of information and communication technology for teaching. She belonged to a group of educators using the free design software tool Canva for creative pursuits. The children quickly mastered the software, and soon Kei was being asked to design business cards.

Nakahara Mari (left), who reached out online for volunteers for the school, and Kondō Miwa, who stepped up to offer support. (© Power News)

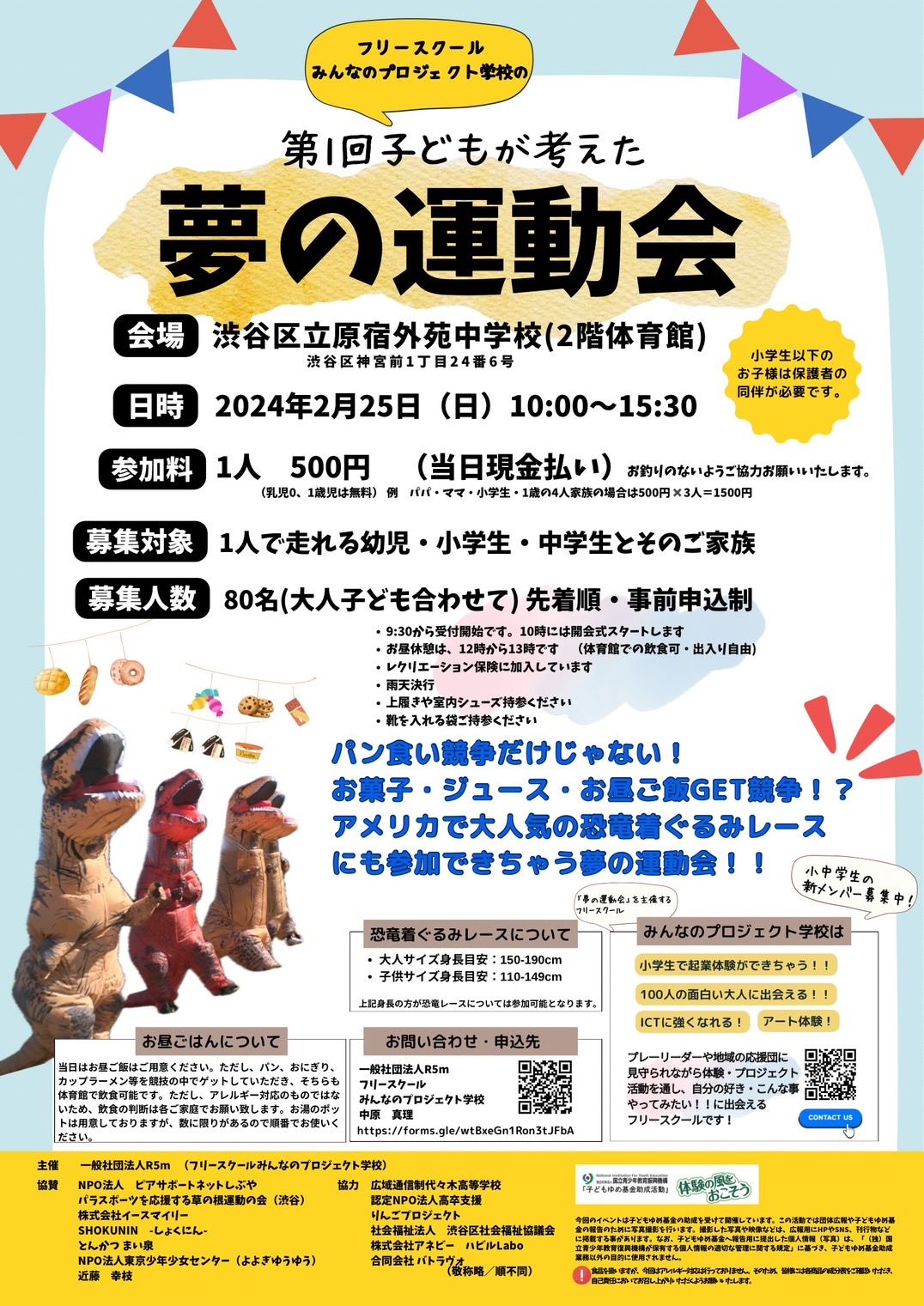

It has been a year now since the school was set up, and on February 25, the group held a sports day at a public junior high school gymnasium in Shibuya to mark the occasion. The idea came from the children, who wanted to have a fun day. They chose the events, which included a bread eating contest and a T. rex race, where competitors wearing dinosaur costumes race, to great comic effect. Help was recruited through social media and word of mouth, attracting 20 high school students and schoolteachers. Thanks to a grant from the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, the event was opened to all children, with up to 80 slots available.

Canva was also used to produce the flyer for the school’s sports day. (Courtesy Project for Everybody School)

Nakahara Mari is gratified at the unexpectedly great number of people expressing understanding of why some children cannot attend regular school and offering support for her project. At the end of 2022, 13 families with similar concerns had formed a parents’ group. Nakahara stressed that her school is there to support children who cannot attend regular school and their parents, who can share their doubts and concerns and be reassured that even though their children may not be in school, they can still feel, learn, and discover something they like to do.

But the difficulties experienced by the children are varied; some have difficulty communicating with strangers or feel uncomfortable in large groups. In such cases, Shibuya city council member Kamizono, who was instrumental in setting up the parents’ group, offers that there are alternatives such as online learning, or connecting one-on-one with an adult sympathetic to a particular child’s issues. Kamizono, who was involved in education, having spent close to 20 years working for an educational support business, came to realize after counseling many parents and children that the framework of conventional school alone is not enough to meet their needs.

Kamizono believes that adults in the community should help turn the whole community into a learning environment. (© Power News)

“I came to feel that through absenteeism, children are trying to say that society needs to change, and that parents should have a choice in seeking a learning environment that suits their children’s particular talents or needs,” says Kamizono.

Connecting Schools and Communities Online

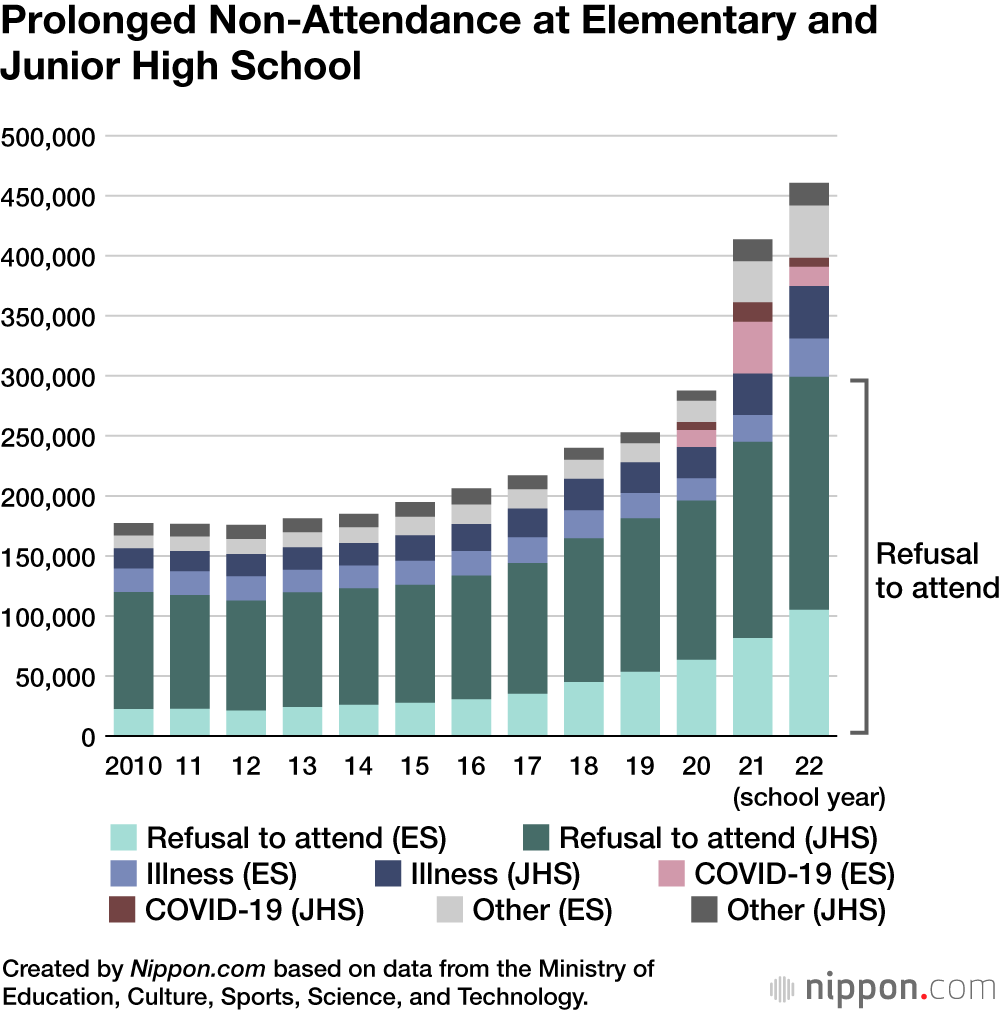

In a survey on problematic behavior and school absence among students in compulsory education (elementary and junior high school) unveiled by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) in fiscal 2022, out of approximately 300,000 children not attending school, nearly 40%, or 110,000, were not receiving support from an education support center or other specialized organization.

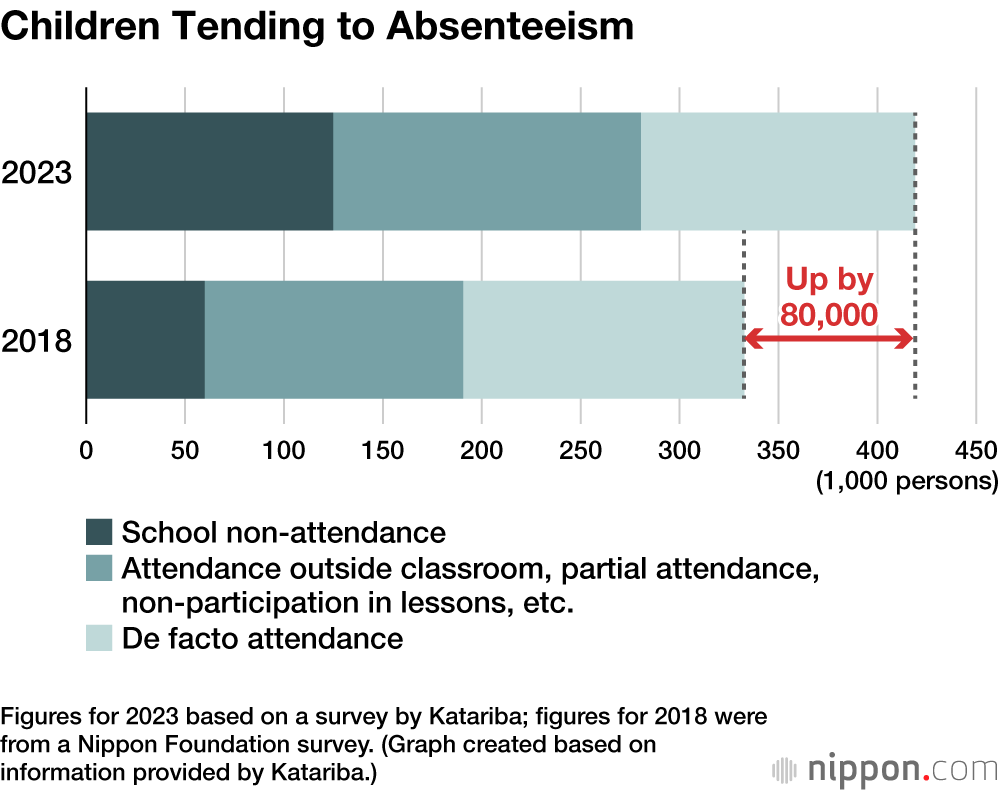

A similar survey conducted by the education-supporting NPO Katariba in October–November 2023 found that an estimated 410,000 children tended toward absenteeism. This figure included children who, while physically present in the classroom and behaving like their peers, were only “de facto present,” in that deep down, they disliked school and likely wished they did not have to attend. In that survey, school non-attendance was 26% higher than in a survey by the Nippon Foundation five years earlier.

Katariba’s Imamura Kumi notes: “About one out of five junior high school students is either absent from school or shows a tendency toward absenteeism. Parents’ and children’s attitudes toward schools are also changing. More diversified channels for learning are needed, and the community at large must also take steps to deal with the issue of absenteeism.”

One such channel for students who do not fit into the standard framework is Room K, an online support program for absentee students launched by Katariba in 2021. Room K is both a place of respite and of learning. Its distinguishing feature is that it assigns specialists to children and their parents, who focus on supporting the families. Room K does not simply provide a program; supporters try to find the learning methods that will help each child flourish and forge connections with society. The program also works with schools and education support centers on an ongoing basis.

What Room K looks like onscreen, as children learn and interact with each other in a virtual environment. (Courtesy Katariba)

Katariba staff member Shirai Sayaka notes that online and in real life, there are differences in the children and the solutions they need. If Katariba can operate in both spheres, with families at the center, it may be possible to work out ways enabling children to learn.

“Room K is operated together with public education authorities and supported by public funding,” says Shirai. “At the moment, it can only be accessed through participating municipalities. It’s schools that are best equipped in terms of resources and knowing which families are not receiving existing support. By working together with the authorities, Katariba wants to support those families to offer them and their children the best path forward.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Reporting cooperation by Power News.)