Japan’s Ig Nobel Prize Winners

Ig Nobel Prize Winner Higashiyama Atsuki and the “Between-Legs Effect” Mystery

Science Education Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The “Between-Legs Effect” Wins Ig Nobel Prize

In 2016 Higashiyama Atsuki received an English-language letter in the mail informing him that his study on the effect of viewing things upside down between one’s legs (the so-called “between-legs effect”), which had originally been published 10 years earlier, had been selected as a candidate for the Ig Nobel Prize.

He ignored it, thinking it must have been a prank of some kind. Then he received another letter, this time in Japanese. The contents of the letter asked him to indicate if he would accept the prize if it were awarded to him. “Imagine that,” he remembers thinking. “It was true!”

The Ig Nobel Prize awards ceremony was held in the Sanders Theatre at Harvard University between acts of an opera. The prize he was awarded was a large clock that was equipped with a hand that indicated the sixty-first second — the “leap second”—and minute and hour hands that puzzlingly indicated seconds. The prize money was $10 trillion, although the unit of currency was not US dollars but rather Zimbabwe dollars, which had been discontinued at the time he received the prize. In fact, the prize money was worth about ¥170.

“It was an extremely humorous awards ceremony,” remarks Higashiyama, “which was fitting to the occasion.”

The Ig Nobel Prize clock with a leap-second hand. (© Power News)

The 10 trillion Zimbabwe dollar note that Higashiyama received as prize money. (© Power News)

Higashiyama began his “between-legs effect” research in 1996. Since he was younger he sensed that there were numerous constraints in the world of psychological research in Japan, and as a result he intentionally submitted his work to English-language publications to increase his chances of publication. “Although my work was quite dull,” he comments, “if I published it in English there were people who would read it. This more than anything else made me happy.”

What exactly was this research that he modestly describes as “dull”?

Optical Illusion Disappears When Positioned Sideways

“Viewing things between one’s legs,” Higashiyama explains, “entails bending at the waist and looking at one’s surroundings upside down from between the legs. When one does this, distances and colors appear differently.”

At Higashiyama’s urging, I bend forward and take a look at a forest through my legs. Viewed in this way, the entire scene seems farther away, the trunks, branches, and leaves of the trees seem to be smaller, and the distances between all the various objects in sight seem to shrink in size as well. It also seems that the shapes and colors are clearer than when viewed in the normal way.

When I express surprise at the wonders of the human sense of sight, Higashiyama counters: “It isn’t sight per se, but rather the influence of the body.”

“In our research,” he continues, “we refer to things we can see as ‘visual information,’ while we refer to phenomena that occur as a result of changing the position of the body as ‘physical information.’ The ‘between-legs effect’ is strongly affected by this physical information. This is what I have found through a process of collecting data and repeated experimentation.”

Higashiyama demonstrating between-the-legs viewing. (© Power News)

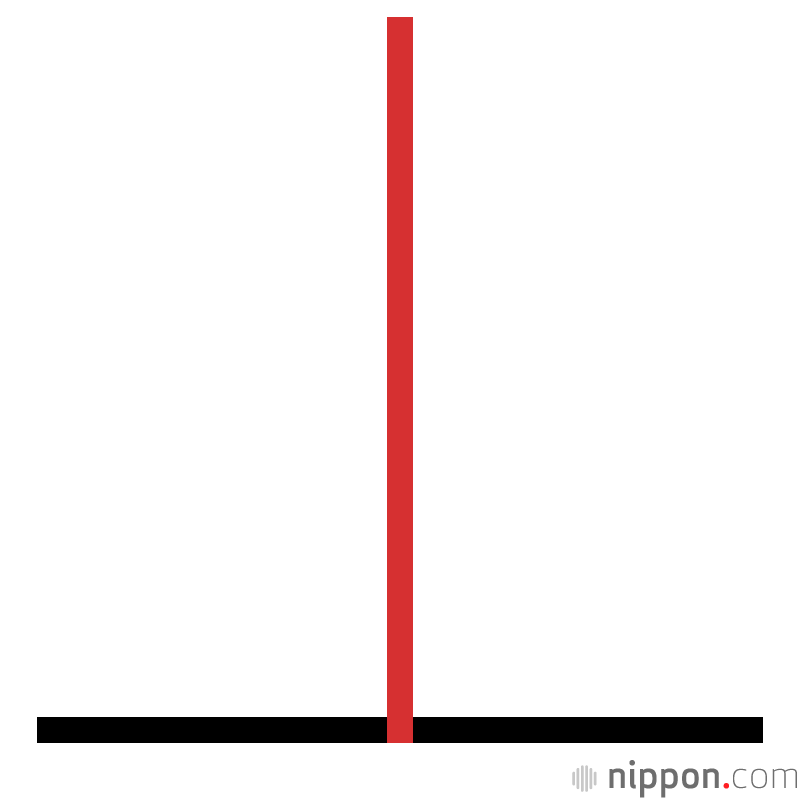

While still in his early thirties, Higashiyama began studying the “horizontal-vertical illusion” in an attempt to identify the relationship between physical and visual information. The horizontal-vertical illusion is a phenomenon in which the vertical line appears longer when a horizontal line and a vertical line of the same length are drawn. For example, it has been shown that when a building that is in fact 10 meters both along its frontage and in height is viewed, it seems to the viewer that the height is 1.4 times the width, making the building look 14 meters tall.

This has been included in textbooks and has led to the widespread belief that visual information causes optical illusions. But Higashiyama thought that they may be caused by physical information as well, so he had multiple students view a building and asked them how it appeared to them.

The vertical and horizontal bars are of the same length, but the horizontal-vertical illusion makes the vertical bar look 1.4 times longer.

The results he obtained came as a shock.

“When they viewed the building from a normal standing position, its appearance to them was exactly as explained in textbooks,” Higashiyama explained. “That is, the vertical measurement appeared longer than it is in reality. But when I had them view it while lying on their side, some of them reported that the vertical and the horizontal lengths looked the same. In other words, we discovered that when lying on one’s side, the horizontal-vertical vertical illusion does not occur.”

No textbook includes mention of one’s visual perception changing when one is in a different physical position. What was shocking about his discovery was that even this small deviation from reality might call all textbooks into question.

This was how Higashiyama arrived at the conclusion that it was necessary to study whether the horizontal-vertical illusion was due to visual or physical information by supplementing his initial results with experiments in which volunteers viewed objects upside down from between their legs.

Myth Arose in Nineteenth Century Textbooks

When most people hear “viewing between one’s legs” they probably think of Amanohashidate, a tourist spot overlooking Miyazu Bay in northern Kyoto Prefecture. Ancient texts state that Izanagi, the deity that created Japan, linked heaven and the earth with a ladder known as the ama no hashidate. Based on this ancient legend, people look at the scenery there upside down from between their legs in order to experience the illusion that the land bridge across the bay presents a stairway to the heavens. There are also regions of Japan where the folklore says that one can see ghosts, the world of spirits and demons, or the future by looking upside down through one’s legs. This fascination with looking through one’s legs comes from the fact that it allows people to see the world in a way that is different from normal.

Between-the-legs viewing at Amanohashidate. (🄫 Pixta)

The fact that this phenomenon was known in antiquity led to attention from researchers in the past. Papers written on the subject of between-the-legs viewing were published in Japan prior to World War II. Even outside Japan, there is a textbook on experimental psychology published toward the end of the nineteenth century that mentioned the “between-legs effect.”

But as far as Higashiyama was concerned, these older works lacked sufficient objective data and contained poor evidence.

Thinking that he had to take the time to research the issue for himself, Higashiyama had over 200 students participate in an experiment, many from Ritsumeikan University.

The experiment consisted of the following: In step 1, he had them view a scene standing up in the normal way. In step 2, he had them view the same scene through “prism goggles” that made the scene look upside down. The third step had them take off the prism goggles and look at the scene again, this time through their legs. Finally, in the fourth step, the students looked at the scene through their legs while wearing the prism goggles. A minimum of 50 students performed each of the four steps. Then, he interviewed the students to discover how the scenes appeared to them.

The key to this experiment was the use of the prism eyeglasses. The results showed that in step 2 the scenes appeared similar to how they appeared in step 1, but that in steps 3 and 4 objects that seemed to be far away appeared smaller than they did in step 1. In other words, the between-legs effect was found to be mainly due to physical information rather than visual information.

Experimenting with 200 Student Volunteers

| Way of Viewing | Appearance |

|---|---|

| (1) Upright | Normal |

| (2) Upright with prism goggles | Similar to (1) above |

| (3) Between the legs | Large objects located far away look small, making it difficult to determine distance |

| (4) Between the legs with prism goggles |

“We clearly established that the physical factor is strongly linked to the between-legs effect,” says Higashiyama.

Speaking from the perspective of a psychologist specializing in spatial perception, Higashiyama further states that “The physical factor must not be ignored in the field of psychology. I believe that finding evidence of this factor is of extreme importance in the world of psychology, where the physical is often overlooked.”

Psychology Without Evidence

Higashiyama has misgivings about current-day psychology.

Many studies place importance on overt, conscious actions like seeing and listening. And some psychologists conclude that people are of one personality type or another based on questionnaires that lack evidence, and which are therefore indistinguishable from fortune-telling.

“So, people have biases in their understanding,” explains Higashiyama. “The same importance as placed on sight and hearing has to be placed on physical information as well, and conclusions must be based on evidence. Researchers need to be aware of the fact that the field of psychology runs the risk of changing people’s lives.”

Looking back to that day in 2016, in spite of the fact that Higashiyama finally realized that being selected as a candidate for the Ig Nobel Prize was not a joke, he hesitated to accept the prize. What convinced him was young people.

“My research is dull and is rarely praised,” says Higashiyama. “But I wanted to let the next generation of researchers and students know that someone was paying attention. If accepting the Ig Nobel Prize could achieve this goal, I thought, then so be it.”

The Ig Nobel Prize certificate presented to Higashiyama. (Courtesy of Higashiyama Atsuki)

After receiving the prize, the Alumni Association at Ritsumeikan University began talking about between-the-legs viewing, and Higashiyama suddenly found that he had far more invitations to lecture on his findings at conferences held by academic associations in fields like medicine and economics. And he was the subject of increased media interest as well.

“I was happy that I had so many opportunities to discuss the details of the research I’d been conducting for so long,” he says.

What Higashiyama always keeps in mind while conducting his research is identifying evidence, as well as avoiding becoming totally immersed in a single research topic by involving himself in multiple projects at the same time. If he reaches an impasse in one study, he can shift his attention to something else, which often leads to new ideas, he says. Although this method means that it may take longer for him to complete each project, he says that his sense of satisfaction far outweighs the extra burden.

Currently, Higashiyama is working on a project called “The perception of the direction of the arms and body and the effect of adapting to that direction.”

Higashiyama explains: “The subject lifts upward his forward outstretched arms with his eyes open. He holds that pose for a short while and then returns his arms to the horizontal position. This is simple for subjects to do. Then he performs the same movements but now with his eyes closed. This time, his arms do not return to the horizontal position but rather are angled slightly upward. This showed that vision cancels out physical adaptation.”

Higashiyama’s lifelong research interest is the relationship between the visual and the physical. When asked what his greatest joy in his research is, he responds as follows.

Professor Emeritus Higashiyama Atsuki. (© Power News)

“I’m most happy when I talk about my research and the person I am talking to seems interested in it. When I won the Ig Nobel Prize, it was a pleasure to know that people from around the world thought my research into the between-legs effect was interesting.”

The term “pleasure” is one that is without a doubt highly significant to most researchers. To this day, Higashiyama continues to collect data and repeat experiments in an effort to feel that “pleasure” once again.

(Originally published in Japanese. Interview and text by Wakabayashi Rio and Power News. Photos by Power News except where otherwise indicated.)