Japanese Traditional Annual Events

Hazuki: Hachiman Festival, Autumn Moon Viewing, and Other August Traditions

Culture Lifestyle Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Tokugawa Anniversary

Hassaku, the first day of the eighth month according to the traditional Japanese lunar calendar, was of greatest importance to the ruling Tokugawa regime. It marked the day in 1590 that founder Tokugawa Ieyasu established himself in the Kantō region, and it was subsequently celebrated in the old capital of Edo as the anniversary of the Tokugawa shogunate.

At the time, Ieyasu was a vassal of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. When Hideyoshi destroyed the powerful Hōjō clan, the warlord redistributed the lands he captured, awarding Ieyasu control over the provinces that make up the modern Kantō region. There is some question as to the exact date Ieyasu took charge of his new domain, with the journal of Tokugawa retainer Matsudaira Ietada recording the date as day 18 of the seventh month. But the first day of the eighth month is when Hideyoshi made his orders official, and thus became the accepted date of the founding of Ieyasu’s rule in the region.

Hassaku celebrations took place inside Edo Castle and were relatively subdued, with daimyō garbed in white katabira, a type of single-layer robe worn by the aristocracy, and formal hakama (pleated trousers), paying their respects to the shōgun.

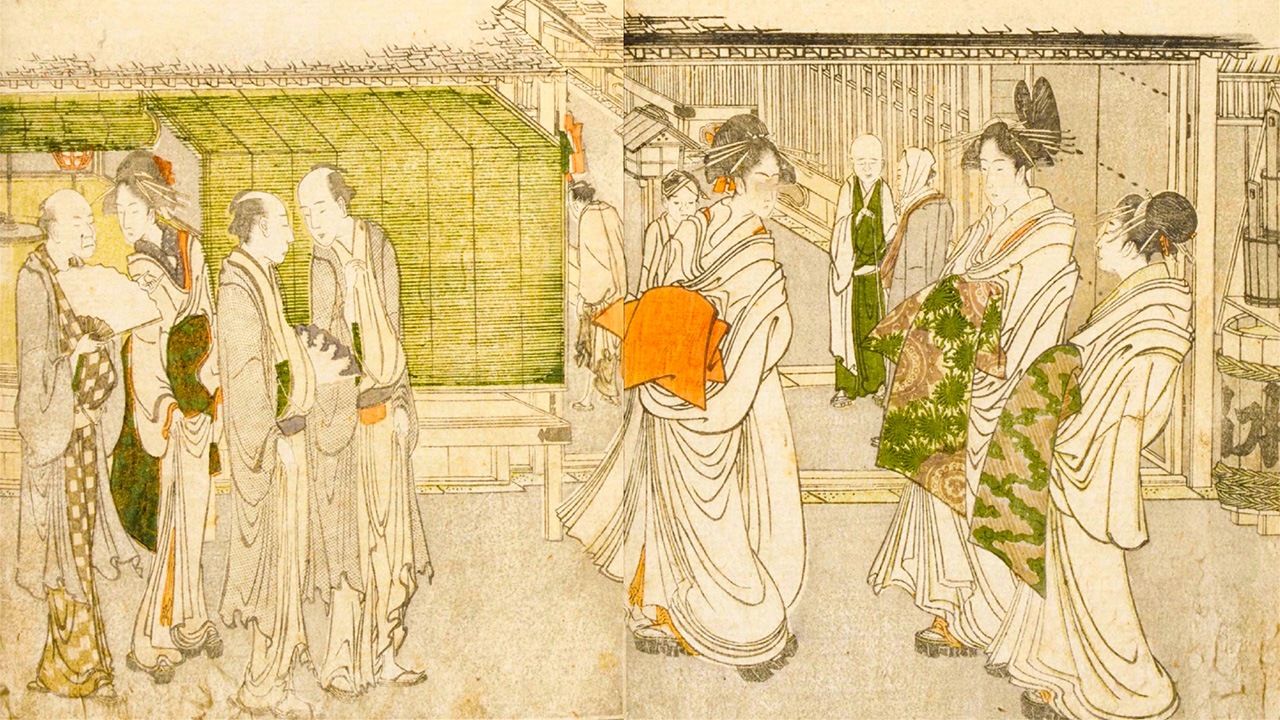

The anniversary was observed primarily by the government, but on the day the women of the Yoshiwara pleasure quarter were known to go about dressed in all-white kimonos in mimicry of the ruling warrior class.

Kitagawa Utamaro depicts women in Yoshiwara clad in white kimono in an illustrated book depicting annual events in the pleasure quarter. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

While associated with the Tokugawa regime, the tradition of celebrating hassaku predates Ieyasu. The day, which falls sometime from mid-August to September on the modern calendar, had long been observed in farming villages as an important seasonal marker. Furthermore, during the Muromachi period (1333–1568), it was customary on hassaku for local daimyō to send gifts of swords and horses to the Kamakura Kubō, the shōgun-appointed administrator of the Kantō region.

Hachiman Festival

The middle part of the August was traditionally when Hachiman shrines around Japan held their annual festivals. In Edo, the celebration at the Tomioka Hachiman Shrine in Fukagawa stood alongside the Kanda and Sannō Festival as the city’s three largest matsuri. In contrast to the Sannō, which was associated with the ruling Tokugawa regime, the Tomioka (Fukagawa) Matsuri was a festival of the denizens of shitamachi—the “low town” near the banks of the Sumida River.

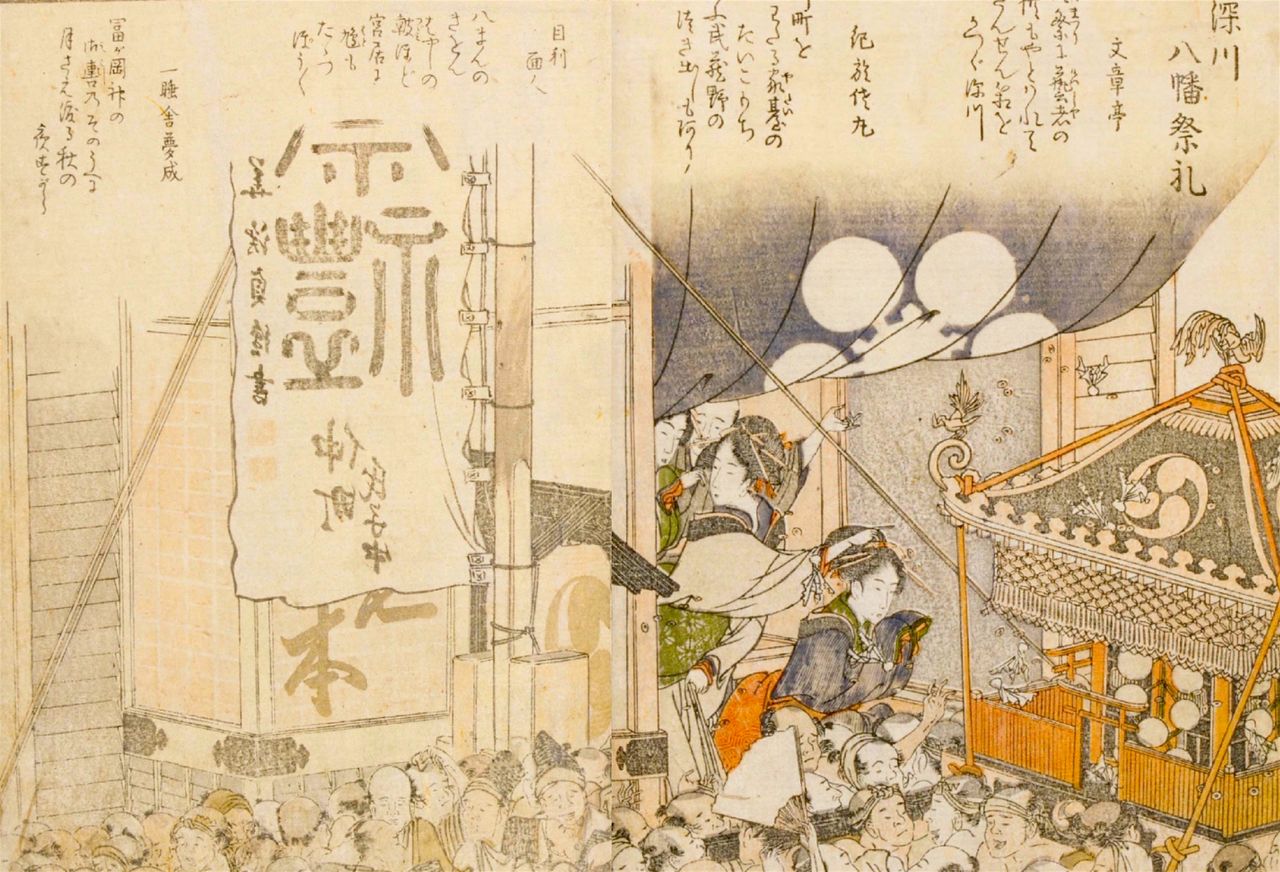

The festival was held on August 14 and 15, and records show it was a raucous occasion, with kagura dances, music, and other performances being held throughout the city. The centerpiece was a massive mikoshi procession that wound its way through the neighborhoods. Adding to the festive environment were countless fluttering banners set out in celebration of the event.

A large banner printed with the characters for sairei (festival) flutters as people carry a shrine through the streets in a work from the series Fine Views of the Eastern Capital at a Glance by Katsushika Hokusai. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

The festival famously drew hordes of celebrants, which in 1807 resulted in disaster when the Eitai Bridge gave way, plunging those standing on the span into the Sumida River. Records put the death toll at some 1,400 souls, many of whom were never found, making it one of the worst manmade disasters the city had experienced. The incident stirred kyōka poet Ōta Nanpo to compose a work that morosely declared “festival today, funerals tomorrow.”

Mid-Autumn Moon Viewing

Today, August is the height of Japan’s summer heat, but by traditional reckoning the eighth month was considered part of autumn, which spanned the seventh to ninth months. Mid-autumn was a time for enjoying the chirping of crickets and other seasonal insects. It was also a time for moon viewing, with the best night of the year for observing the celestial body falling on the fifteenth, known as jūgoya no tsukimi. The custom continues to be observed today in mid-September.

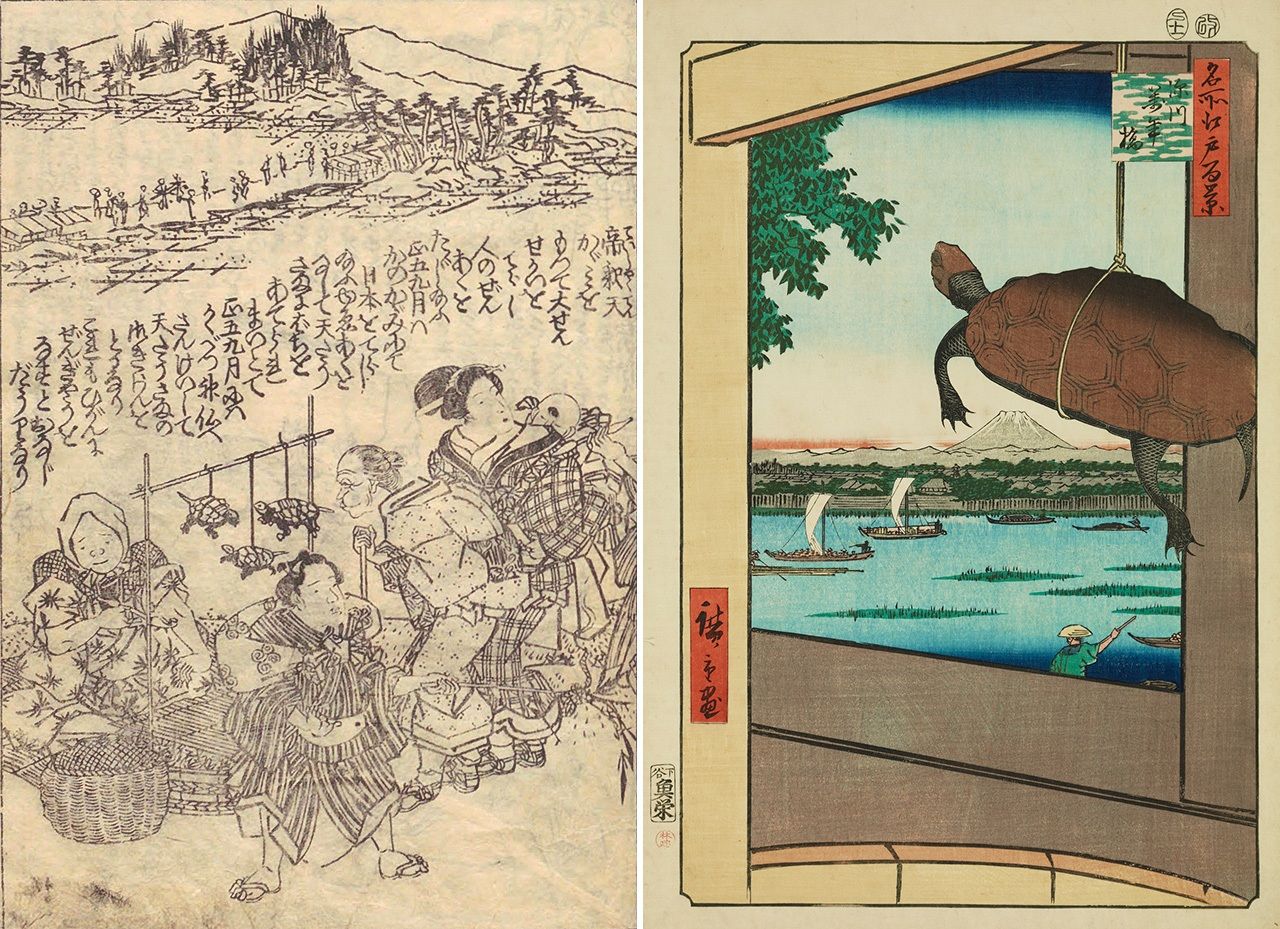

The full moon rises at Dōkanyama as a mother and child collect autumn insects, from Utagawa Hiroshige’s Famous Places in the Eastern Capital. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

There are many theories as to the origins of moon viewing (tsukimi), but as demonstrated in works like The Tale of Genji, it was already a well-established pastime among aristocratic society as early as the Heian period (794–1185). It enjoyed broad popularity among all classes during the Edo period, giving rise to new traditions such as tsukimi dango, round rice dumplings representing the full moon. Accounts from the past describe families busily making these auspicious treats from the morning of the fifteenth in preparation for evening moon viewing parties.

A popular way to take in the full moon among the more affluent residents of Edo was aboard boats plying the Sumida River and other waterways. Among the best-known spots was Nakasu at a place on the Sumida known as Mitsumata, or “Three Forks,” where the banks had been filled in. A vibrant entertainment district with restaurants and teahouses thrived there until 1789, when the government ordered the landfill removed to alleviate flooding upriver. The stretch of water between the bridges Azumabashi and Asakusabashi was also a favored area for boating on the night of the full moon.

Life Release

Another event traditionally observed in the eighth month was hōjōe, in which captured animals were released back into the wild. Based on Buddhist principles, the practice in Japan is credited to Emperor Tenmu (r. 673–686), who banned the consumption of meat in 675 and ordered the release of animals to show the importance of all life.

Hōjōe is closely associated with Hachiman shrines. The Usa Hachiman Shrine in Ōita Prefecture held what is thought to be the first hōjōe festival in 720 during the Hayato rebellion against the ruling Yamato dynasty to placate the souls of those killed in the uprising. In 1187, Minamoto no Yoritomo (r. 1192–99), founder of the Japan’s first shogunal government in Kamakura, sponsored the first hōjōe at the clan’s titulary shrine, Tsurugaoka Hachimangū.

In Edo, hōjōe was conducted during the Tomioka Hachiman Shrine festival and centered around the release of turtles. The custom spawned a cottage industry during the festival, with vendors selling the shelled animals to residents, who in turn released them back into the water. The sight of turtles hanging from cords drew neighborhood children and even inspired a famous senryū poem that depicted the helpless creatures as swimming in the air.

From left: A stall selling turtles in an illustrated work describing seasonal events (courtesy National Diet Library); a turtle swings in the air in Utagawa Hiroshige’s Mannen Bridge in Fukagawa, in the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (Courtesy ColBase).

Other animals sold for release included sparrows, rabbits, and koi carp. Prices varied—turtles typically went for 4 mon, equivalent to around ¥300 in today’s money—making hōjōe a somewhat spendy practice. But the average Edoite considered it a pious act that was well worth the cost.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Women in Yoshiwara clad in white kimono for hassaku from the series Fine Views of the Eastern Capital at a Glance. Courtesy National Diet Library.)