Japanese Traditional Annual Events

Shimotsuki: A New Kabuki Season, “Shichi-Go-San” Celebrations, and Other Traditional Annual Events in November

Culture Lifestyle Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Kabuki Gala

The eleventh month has long been an exciting time for kabuki aficionados, as it marks the start of a new season of performances. It was customary during the Edo period (1603–1868) for kabuki actors to sign with theaters for a one-year period, with contracts running from November to October the following year. The new season kicked off on the first day of the month with kaomise (face-showing) performances that introduced the public to a theater’s lineup of stars and new actors.

Kaomise was a much-anticipated occasion that doubled as an important social event, drawing large crowds of spectators from across society. Those who had the means dressed up for the performances, which were held during the daylight hours starting at sunrise—the beating of the drums announcing the event were said to begin before the first crow of the rooster—and there are tales of female theatergoers spending all night getting ready in order to make the early morning curtain rise.

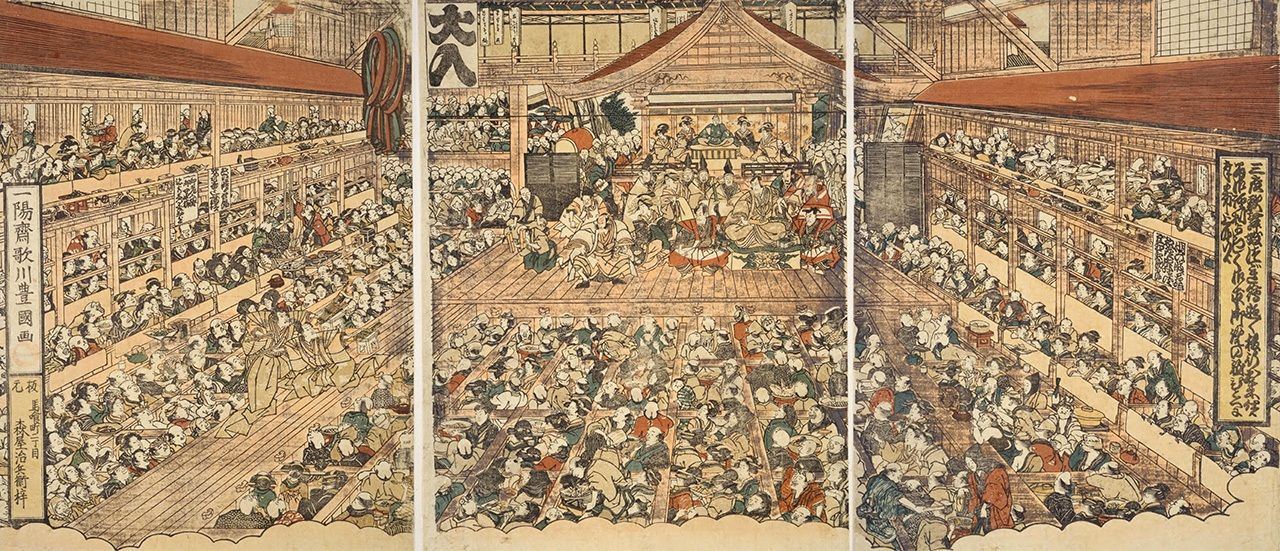

Crowds fill the Nakamuraza theater in an 1817 print by Utagawa Toyokuni. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

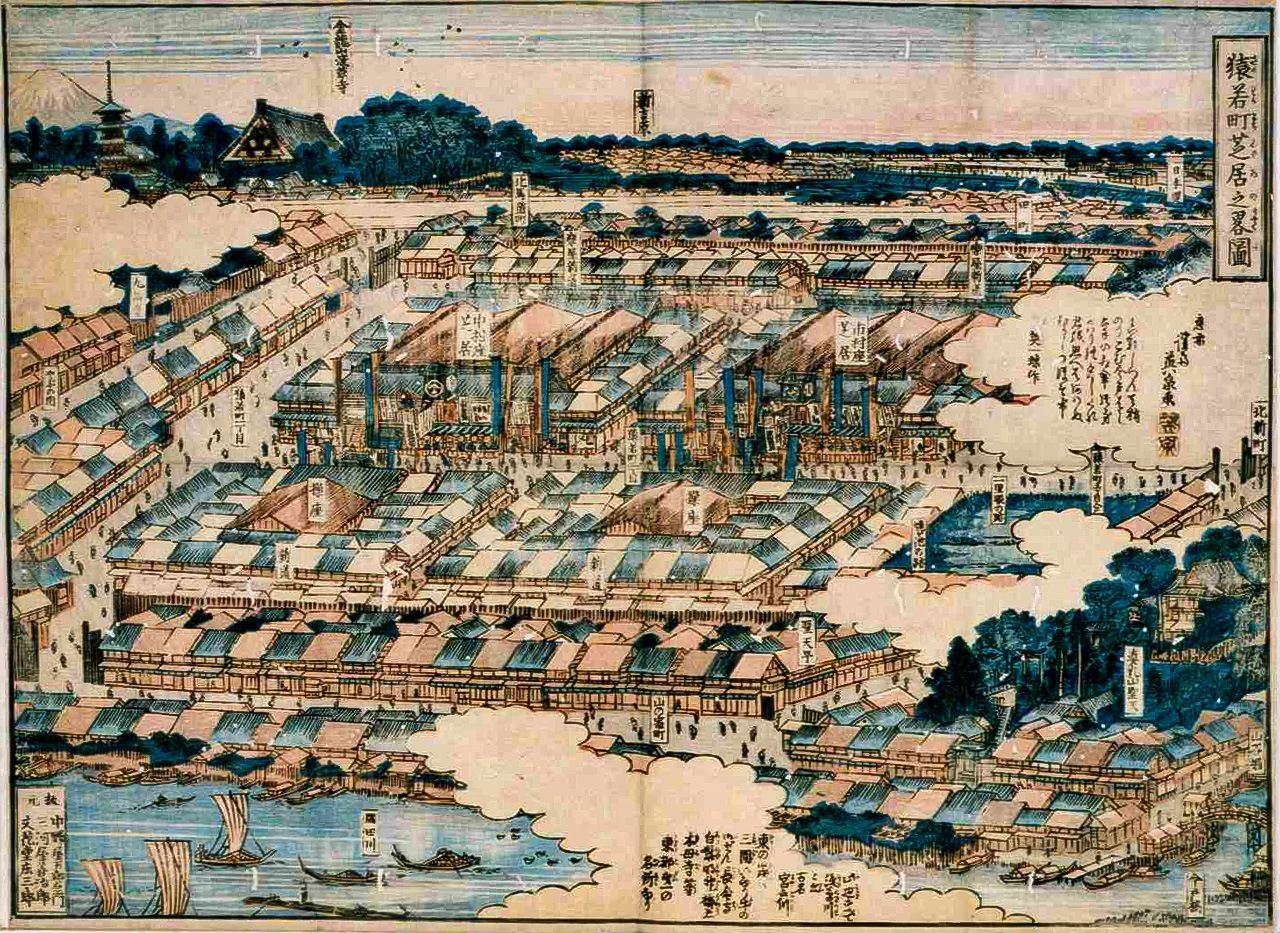

In the capital of Edo, the three main kabuki theaters, Nakamuraza, Ichimuraza, and Moritaza—known collectively as the Edo sanza—attracted droves of spectators for kaomise. Up to the mid-nineteenth century, kabuki performances were held at venues located in different parts of the city, but in 1842 authorities relocated the theaters to Saruwaka-chō in what today is part of the Asakusa district. A fourth theater, Kawarasakiza, is sometimes added to the sanza list in lieu of Moritaza, which was forced to close several times for financial and other reasons.

A print by Keisai Eisen depicts the kabuki theaters Nakamuraza and Ichimuraza shortly after relocating to Saruwaka-chō. (Courtesy Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room)

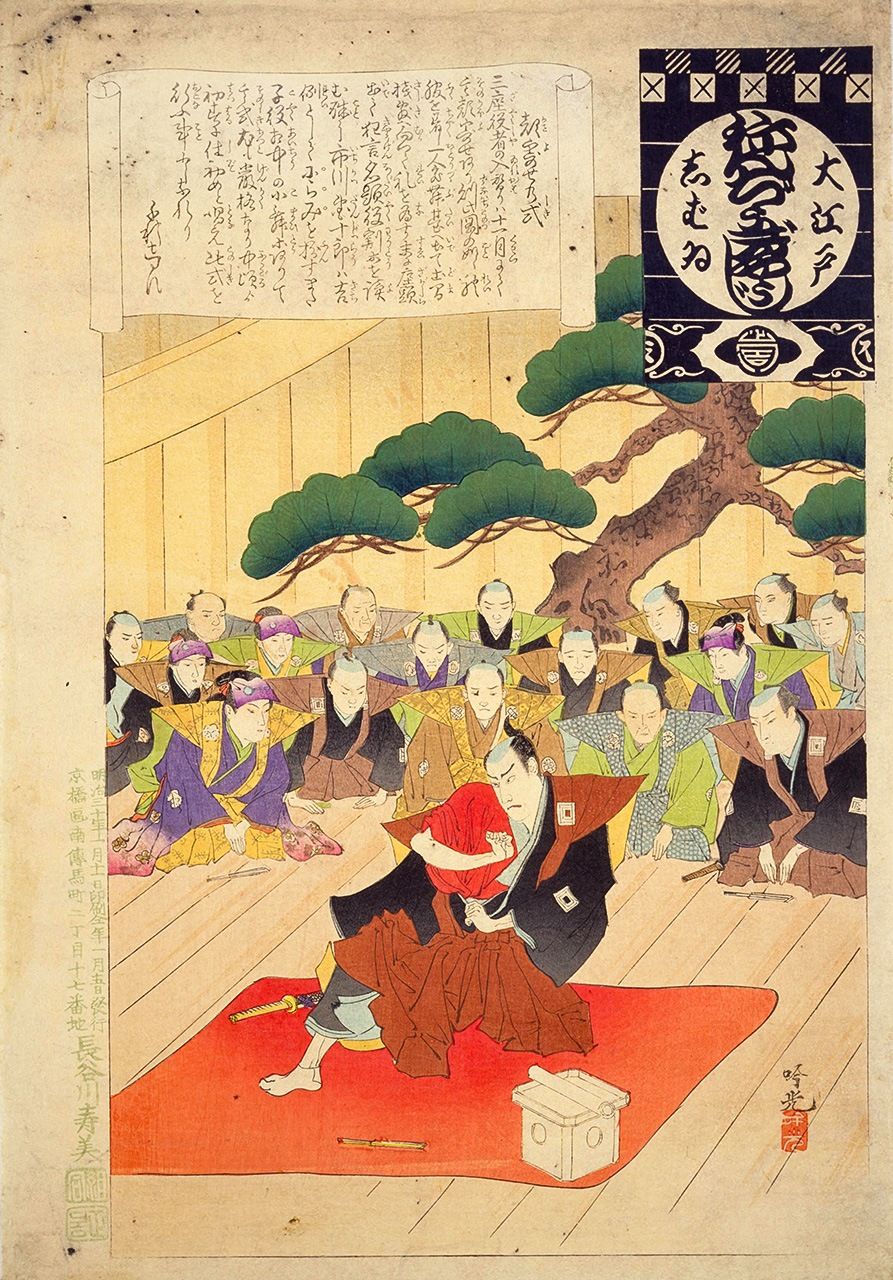

Kaomise included a range of ceremonies and conventions appealing to fans of kabuki, not least of which were performances featuring such superstars as Ichikawa Danjūrō, a pioneer known for his powerful presentation and eye-catching makeup, and other luminaries of the stage like Onoe Kikugorō and Bandō Mitsugorō. (Many of these celebrated names are passed down to new members of their families to this day.)

A kabuki actor strikes a pose during a kaomise performance in an 1897 print by Adachi Ginkō. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Celebrating Children

The fifteenth day of the month features the popular custom Shichi-Go-San—literally “seven-five-three”—in which households with daughters who are three or seven years old, or sons who are five years old, visit a shrine or temple to pray for the health and wellbeing of the children as they grow.

It is unclear when the Shichi-Go-San custom became established in its present form, but one version attributes it to the fifth Tokugawa shōgun Tsunayoshi (r.1680–1709), who hoped to ensure the health and longevity of his young son Tokumatsu, heir to the Tatebayashi domain. Another theory describes the fifteenth being chosen for its association with kishuku, a highly auspicious day based on Chinese astrological reckoning.

The Shichi-Go-San custom has roots in three distinct rites of passage observed for centuries by the aristocracy. The first, kamioki, marked the stage in life when three-year-old girls—and sometimes boys—began to grow their hair out (it was customary to shave the heads of very small children). The second was hakamagi, when five-year-old boys of aristocratic families wore hakama, traditional pleated trousers, for the first time. The last, obitoki, was for seven-year-old girls and marked their first fastening of a kimono with an obi sash.

A print by Torii Kiyonaga shows a family celebrating kamioki (left) and another by Suzuki Harunobu depicts obitoki. (Courtesy ColBase)

In the Edo period, Shichi-Go-San was enthusiastically embraced by the merchant class, with it not uncommon for parents to take their children to temples or shrines with an extensive entourage that could include aunts, uncles, wet nurses, and even apprentices and business associates. Unsurprisingly, the bulk of Edo-period wood-block prints depicting Shichi-Go-San festivities feature well-to-do townsfolk.

Just as today, families dressed up for the occasion. Another familiar aspect is the gifting of chitose ame, long, thin candy that comes in celebratory, colorful bags decorated with turtles, cranes, pine trees, and other symbols of health and longevity. Historical documents attribute the origins of the distinctive candy to vendors of souvenir sweets who hawked their wares near Asakusa around the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

Raking In the Good Fortune

It has long been a custom to hold Tori no Ichi markets featuring the sale of ornamental rakes called kumade. The most venerable of these festivals is said to be the one at Ōtori Shrine in Asakusa. Other well-known markets include those hosted at Shinjuku’s Hanazono Shrine and Fuchū’s Ōkunitama Shrine.

The festivals are held on tori no hi, day of the rooster according to the lunar calendar. Tori no hi follow a 12-day cycle, with two and sometimes three falling in the eleventh month. The days are considered auspicious, although folk belief holds that years with three tori no hi in November are harbingers of fires, an idea that gained traction following the Great Fire of Meireki in 1657, which reduced large swathes of Edo to cinders. The weather leading up to the disaster on January 18 had been exceedingly dry, starting the previous November when the Tori no Ichi, which is believed to ward off calamities, was held. As there had been three tori no hi that year, the famously superstition residents of Edo became wary of san no tori (the third day of the rooster).

The origins of the Tori no Ichi are somewhat complicated, but are generally thought to be rooted in veneration by the warrior class of Yamato Takeru and Amenohiwashi, gods associated with success in war and identified with the eagle (washi). Both deities in time became linked with good luck in general, with their avian connections taking roost in the auspicious tori zodiac sign.

The first Tori no Ichi took place not in Asakusa, but at a different Ōtori Shrine in what today is Tokyo’s Adachi. Both shrines are dedicated to Yamato Takeru, but the one in Asakusa sat closer to the attractions of central Edo, including the pleasure quarters of Yoshiwara, and subsequently came to be preferred by worshippers.

On the day of Tori no Ichi, stalls hawking kumade and other charms line the street in front of the Ōtori Shrine. The fan-shaped rakes are decorated with an array of auspicious symbols, including gold coins, rice bushels, sea bream, and smiling okame masks. The shrine office also sells miniature versions called kakkome. The festival attracts business owners and others, who buy kumade to “rake in” good fortune in the coming year.

A proprietress and shop boy return from the Tori no Ichi with a kumade in an 1854 print by Utagawa Toyokuni. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

It is unclear when kumade took on their characteristic flamboyance, but judging from Edo-period ukiyo-e, they were already known for their flashiness by the end of the eighteenth century. There is a popular belief that buying a larger kumade than before will assure greater luck in the year to come.

Kumade on sale at the Tori no Ichi. (© Pixta)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The bustling streets of Saruwaka-chō outside the Kabuki theater Ichimuraza, as depicted in an 1854 print by Utagawa Hiroshige. Courtesy National Diet Library.)