Japanese Traditional Annual Events

Kannazuki: Setting Up “Kotatsu,” Public Sumō Bouts, and Other Traditional Events in October

Culture Lifestyle Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Kotatsu and Wild Boar

The tenth month of the traditional lunar calendar, called Kannazuki, traditionally brought with it the first chilly signs of the impending winter. In preparation for the coming cold, people opened the sunken hearths that were fixtures of most traditional homes and set up kotatsu, heated tables insulated with heavy skirting or quilted futon coverings. This kotatsu-biraki was observed on the first day of the boar, known as inohi or gencho. Today, the tradition typically falls in early November.

A man lights the coals of a sunken hearth as women set up a kotatsu in the 1734 work Ehon waka no ura. (Courtesy National Institute of Japanese Literature)

The significance of the day of the boar as the time for dusting off the household kotatsu stems from the ancient yin-yang cosmology system. Based on the flow of the five elements of wood, fire, earth, metal, and water, the philosophy strongly associates boar with the last of these. Modern kotatsu are electric, but in the past they were heated with coals burned in a brazier, and the boar-water correlation was believed to ward off fires.

It was customary on the day to enjoy inokomochi, rice cakes filled with sweetened bean paste and marked with dark stripes resembling those of boar piglets. The seasonal confections, which can still be found at some traditional confectioneries, carry the hope for health and a prosperous family, a belief rooted in the boar’s reputation for fecundity.

The sesame seeds and dark lines of inokomochi bring to mind the speckles and stripes of baby boar. (© Pixta)

In many rural areas, bands of children would parade through neighborhoods striking the ground with tightly packed bundles of rice straw and chanting rhythmic phrases in the belief that it would invigorate the earth and bring a bountiful harvest. Residents would reward these efforts with gifts of inokomochi.

Honoring Ebisu

Japan’s multitude of Shintō deities are said to gather at Izumo Taisha in the tenth month of every year—the name Kannazuki literally means “month without gods,” the result in the rest of the country while they are gathered there. Subsequently, few shrines hold festivals at this time of year. One exception is Ebisu-kō, a festival honoring Ebisu, who is purportedly delegated the job of looking over the wellbeing of people in the absence of the other gods.

Depicted as a plump, smiling figure carrying a giant sea bream, Ebisu is one of Japan’s Seven Gods of Fortune and the patron deity of fishing and commerce. During the Ebisu-kō festival, traditionally held on the twentieth day of the month, merchants in Edo (now Tokyo) and other cities would host customers at shops, where they would offer up a sea bream to the deity before embarking on a frenzied spree of buying and selling. Large deals drew excited responses from attendants, with the lively atmosphere believed to set an auspicious tone ahead of the closing months of year, an especially busy period for merchants and artisans.

Merchants get into the spirit of the Ebisu-kō festival in a print by Yōshū Chikanobu depicting annual events in Edo. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Despite his lucky image, Ebisu had a murky past. He is associated with Hiruko, the malformed child of the creator gods Izanagi and Izanami, who the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters) describes casting the unwanted offspring away to sea in a reed boat. Later legends, however, have the boat drift back to shore and the child lovingly raised. Some accounts put the location of the boat’s landing at Nishinomiya in present-day Hyōgo Prefecture, where the head shrine of the Ebisu sect of Shintō stands.

From this early connection to being cast adrift on the sea, Ebisu was worshipped as a deity of fishing, bringing bounties carried on the waves. This propitious reputation was later extended to such spheres as commerce, with Ebisu coming to enjoy broad popularity among the common classes. Today, ebisugao (Ebisu face) is still used to describe a warm, smiling visage.

An interesting spinoff of the Ebisu-kō festival that developed in the early Edo period (1603–1868) is the bettara-ichi, a market dedicated to a popular type of pickled daikon radish. The market took place around the Takarada Ebisu Shrine in Nihonbashi on the eve of the Ebisu-kō festival and featured stalls selling the savory radishes. It is still held on October 19 and 20 each year.

Visitors to the bettara-ichi stroll through the streets around the Takarada Ebisu Shrine in Utagawa Hiroshige IV’s Edofunai ehon fūzoku ōrai, a work depicting the manners and customs of the old capital. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

Bettarazuke is made by brining a whole radish and then pickling it in sugar and kōji, with the onomatopoetic betta expressing the stickiness of the concoction.

Sumō Tradition

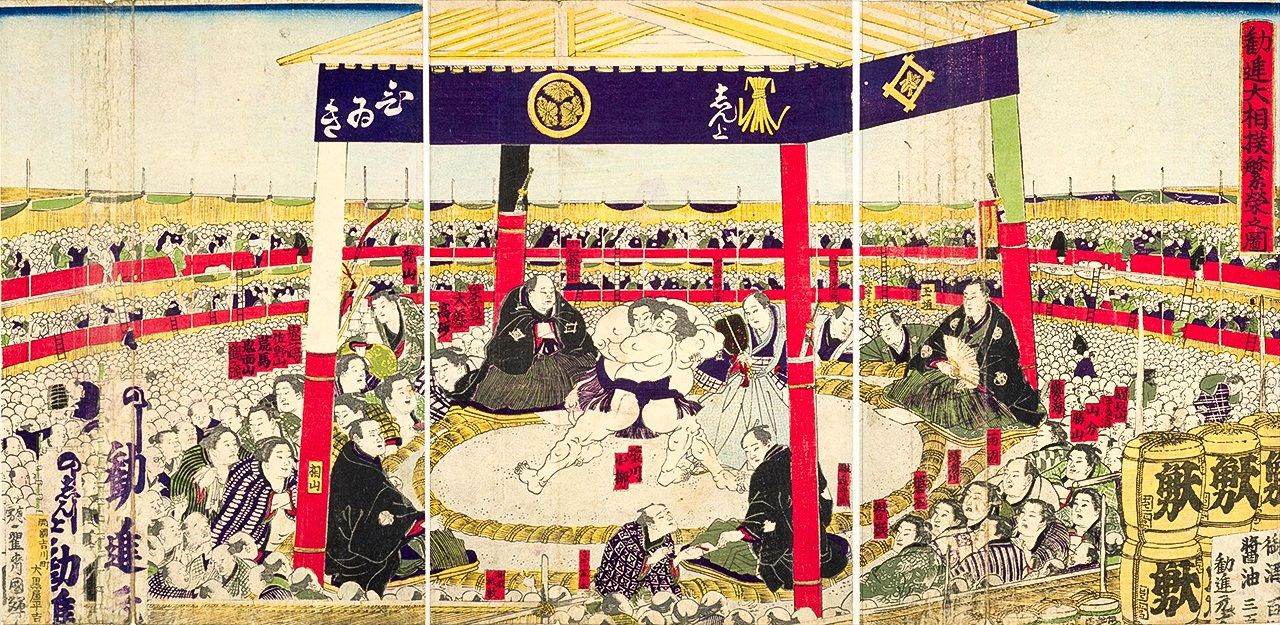

The early years of the Edo period also saw the rise of kanjin-zumō, public bouts held in spring and autumn at different Buddhist temples and Shintō shrines in the capital. The predecessor of modern sumō, these popular events featured wrestlers grouped in east and west factions facing off against one other, with proceeds of tournaments going toward construction and repairs at the temple or shrine hosting the event. The autumn edition typically took place in the latter half of the tenth month and was held at different venues, before eventually settling at the temple Ekōin in Ryōgoku in 1833.

The stands around the ring are packed with spectators in a depiction of kanjin-zumō by Utagawa Kuniteru II. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

The tournaments helped spread the popularity of sumō, with each era featuring its own star wrestlers. Many of the techniques, rituals, and other trappings familiar to fans of the sport today were developed and refined through kanjin-zumō.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner image: A print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi depicting the ring-entering ceremony during a kanjin-zumō tournament at the temple Ekōin in 1849. Courtesy Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room.)