Japanese Traditional Annual Events

Fumizuki: Star Festivals, Welcoming Departed Ancestors, and Other July Traditions

Culture Lifestyle Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Wishing on the Stars

One of Japan’s best known summer traditions is tanabata, the star festival, observed on July 7. Cities like Sendai in Miyagi Prefecture and Hiratsuka in Kanagawa Prefecture draw crowds with elaborate displays of decorations marking the once-yearly meeting of the weaver star Orihime (Vega) and the cowherd star Hikoboshi (Altair).

The folktale of the two star-crossed lovers dates from the era of the Northern and Southern dynasties (439–589 CE) in China and tells of a celestial weaver and herder who fall in love and marry. Once wed, they begin to neglect their duties, angering Tentei, the emperor of heaven and father of the weaver, who exiles the pair to opposite ends of the “river of heaven” (Milky Way) and grants them just one meeting each year.

The story likely crossed to Japan during the Nara period (710–94), taking root and merging with the legend of tanabata-tsume, the celestial maiden who weaves clothes for the gods, and other native elements.

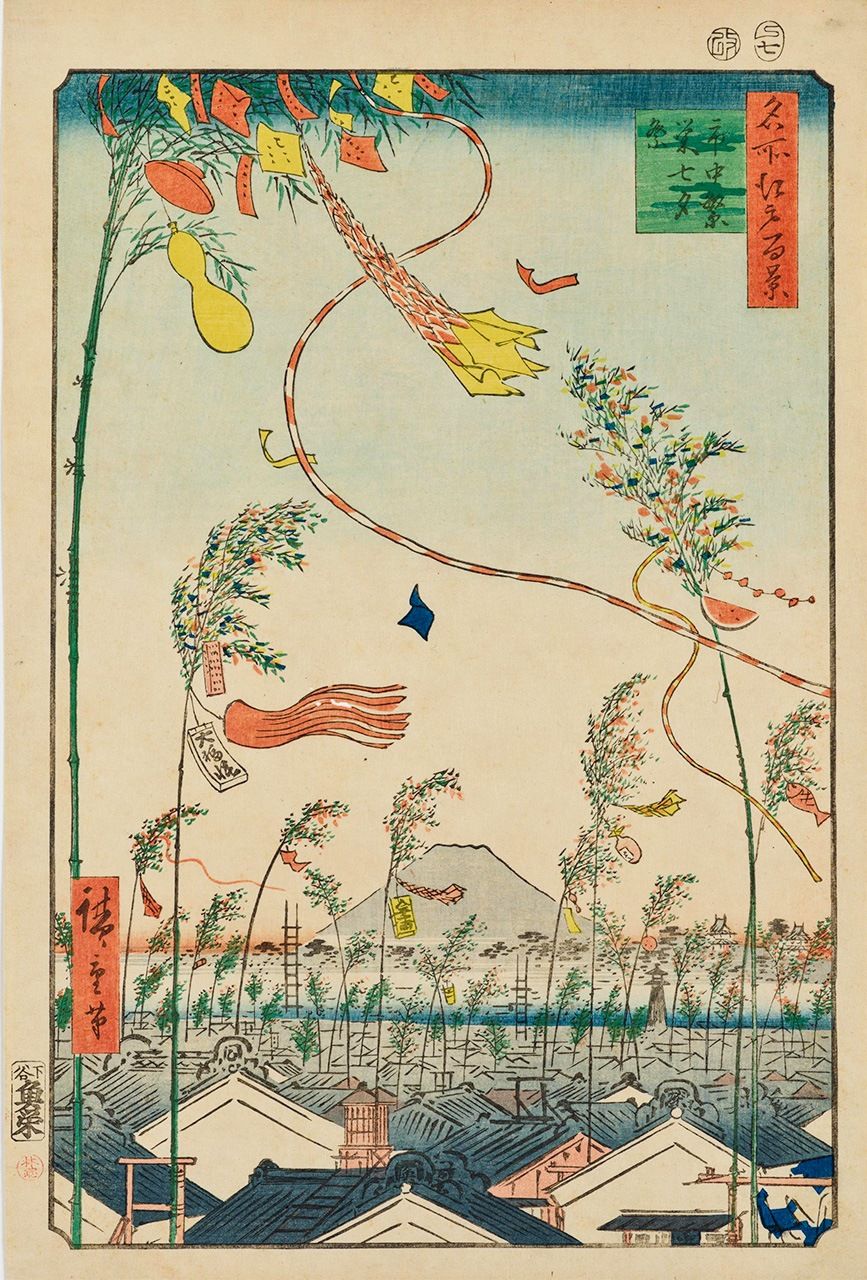

In the Edo period (1603–1868), the ruling Tokugawa regime officially enshrined tanabata as one of five traditional seasonal festivals (gosekku), and it was during this time that the holiday’s characteristic custom of writing wishes on tanzaku and hanging the colorful strips of paper from branches of bamboo first appeared. It was customary to attach the branches to poles, and the illustrated work Tōto saijiki published in 1838 describes row upon row of tanzaku-laden bamboo branches towering above rooftops in the capital of Edo. It was not uncommon for households to vie to have the tallest decorations in the neighborhood.

Brightly colored tanzaku flutter from a rooftop forest of bamboo branches in an 1857 by Utagawa Hiroshige in his series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. (Courtesy ColBase)

The custom is still widely observed today, although broad-leafed bamboo (sasa) has largely replaced taller varieties common in the past, and decorations are typically displayed indoors in the entrance of homes rather than from rooftops.

Floral Glory in the Mornings

The neighborhood of Iriya in Tokyo’s Taitō hosts a large morning glory festival each July 6–8 at the temple Shingenji. The popularity of morning glories, called asagao in Japanese, dates from the late Edo period. At the time the decorative plants were all the rage among okachi, low-ranking samurai who typically spent their days toiling away in magistrate offices. They were initially associated with the area where the okachi lived, today’s Okachimachi, but the focus shifted to Iriya as gardens in the district developed ever-more distinct varieties.

The Iriya morning glory market depicted in an 1866 print by Hiroshige II. (Courtesy Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room)

Iriya’s morning glory market attracts swarms of visitors with its vast array of flowers. (© Pixta)

Iriya’s morning glory market was first held sometime in the early part of the nineteenth century, with the popularity of the flowers reaching its zenith in the succeeding decades. The festival continued until 1913, disappearing briefly before being reestablished in 1948. Today it features over 100 stalls selling morning glories and other items, and has some 120,000 plants on offer.

Ancestral Spirits

The summer festival of Obon is typically observed during the middle part of August. But many regions still celebrate the custom, also known as Urabon’e, according to the traditional Japanese calendar on the thirteenth to eighteenth days of the seventh month.

In the Edo period, towns and neighborhoods took on a lively air during Obon. In the days leading up to the holiday, sellers of tamadana, stands for displaying offerings, and other goods hawked their wares. On the first day, residents lit the way for returning spirits with fires called mukaebi—a practice still observed in many areas—and throughout the period priests wandered the streets chanting prayers in return for alms.

Mukaebi fires welcome ancestral spirits home for Obon. (© Pixta)

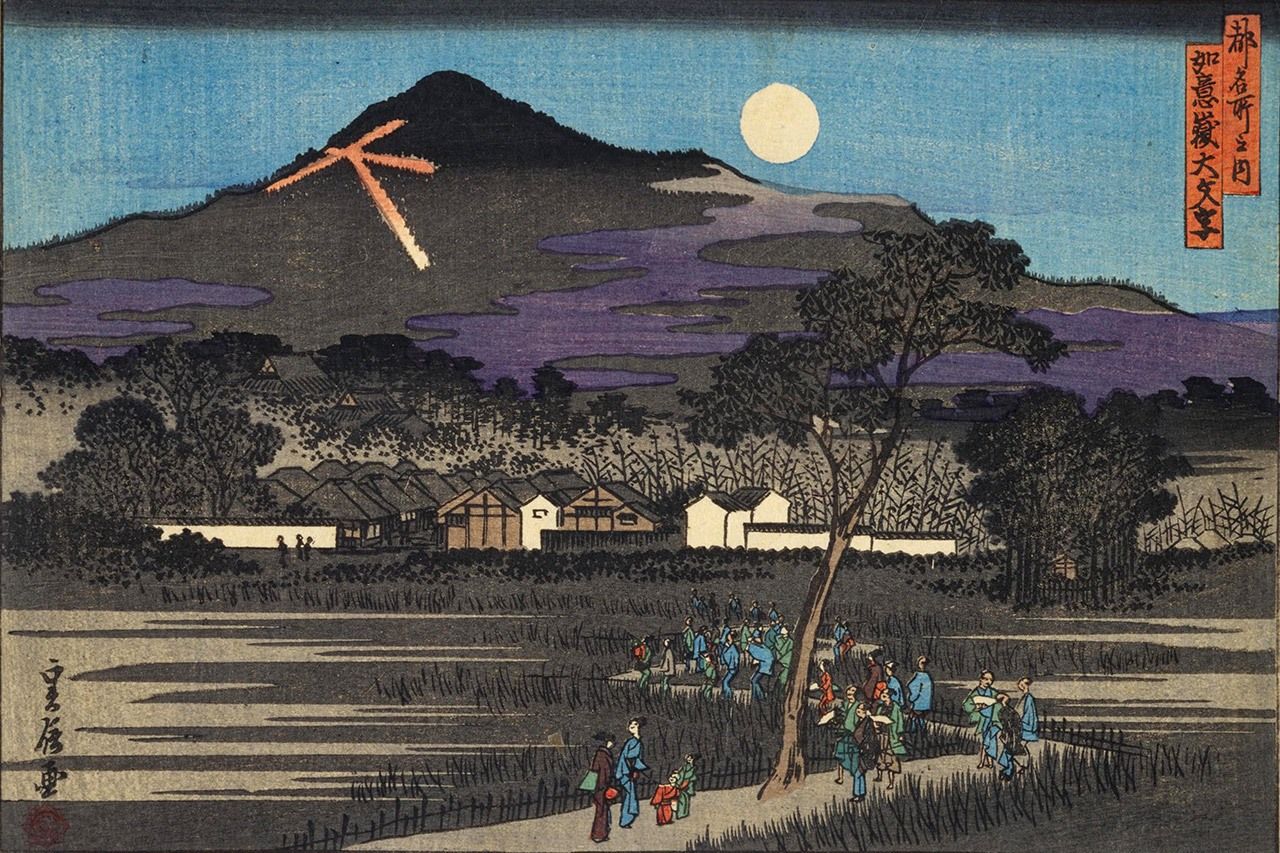

A bonfire depicting the kanji “big” burns on Kyoto’s Nyoigatake, in the series Famous Places in the Capital by Hasegawa Sadanobu. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

The practice of lighting huge bonfires on five mountains around Kyoto during Obon dates back to the seventeenth century. The five bonfires (Gozan Okuribi) depicting boats and kanji characters with Buddhist significance are today lit on the night of August 16, more closely matching the seventh month by the traditional lunar calendar, and are thought to light the souls of the dead on their journeys back to the spirit world.

Another Obon custom is bon odori (bon dancing) performed for the visiting spirits. The dances developed from earlier religious practices, but by the mid-seventeenth century they had evolved into a type of folk entertainment marked by lively music and colorful decorations. The mixing of the sexes at dances was a point of concern for Tokugawa authorities, who started regulating the events in 1649 and even banned them outright for a time in large cities starting in 1690 to preserve public morals.

Waiting for the Moon

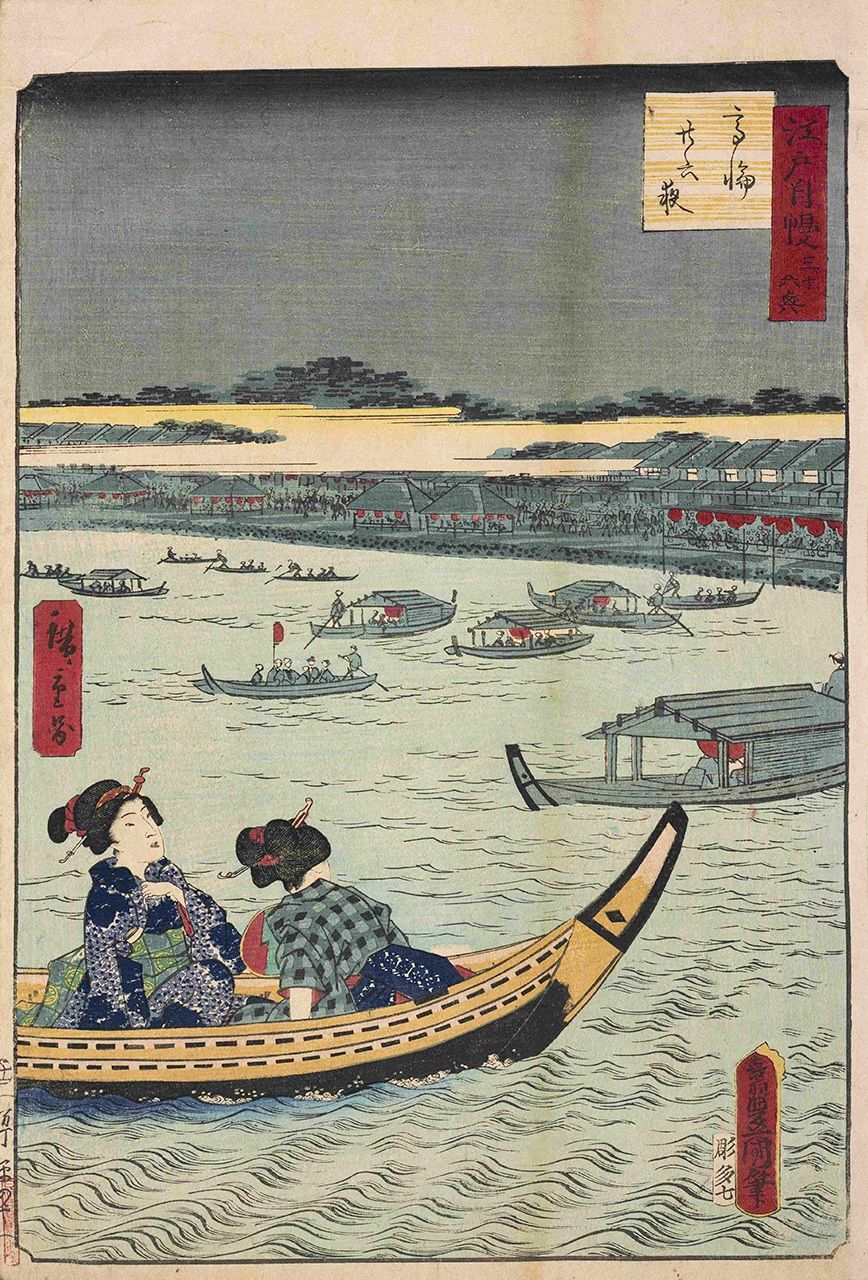

Moon viewing has long been a popular pastime, and one of the most important dates for it in Edo was the twenty-sixth day of the seventh month, known as nijūroku-ya, when the waning crescent moon appeared in the sky. People gathered in hilly areas around the capital—Susaki in Fukagawa, Yushima Shrine, Iidabashi’s Kudanzaka—to eat and drink in the cool of the evening in expectation of the celestial body’s appearance.

The coastline from Shinagawa to Takanawa was an especially coveted spot, offering a fully unobstructed view of the spectacle. Prints and other works of the day depict the lively atmosphere, with all matter of delicacies and entertainment on offer.

It was believed that the rising moon would be followed by an Amida triad (the Amida Buddha flanked by the bodhisattvas Kannon and Seishi), providing a religious veneer to what was otherwise an excuse to enjoy the early autumn season.

Boats ply the waters at Takanawa carrying revelers awaiting the moon in an 1864 print by Utagawa Toyokuni III and Utagawa Hiroshige II. (Courtesy Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library Special Collection Room)

Other Traditional July Events

| Event | Day | |

|---|---|---|

| Idogae | July 7 | A day set aside for workers to clean and conduct maintenance on communal wells |

| Nochi no yabuiri | July 16 | The second of two days a year live-in apprentices were given leave to rest or return home |

| Enma no saijitsu | July 16 | The day Enma, the Buddhist god of hell, rests; it was customary to visit temples associated with the deity |

Parishioners crowd the confines of a temple in the Kuramae area of Asakusa to pay their respects to a giant image of Enma. Normally closed to the public, the statue was displayed on July 16. (Courtesy ColBase)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Katsushika Hokusai’s print Morning Glories and Tree-Frog from a series featuring flowers. Courtesy ColBase.)