Japan’s Innovations in the Sporting World

Kusakura: Pioneering Jūdō Uniform Maker with a Century of Expertise

Sports Economy Economy- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Changing with the Sport

From its humble beginnings in the late nineteenth century, jūdō has transformed into an international sport. In its evolution from an obscure Japanese martial art to an Olympic event, it has integrated new techniques and strategies brought by the expanding population of jūdōka with backgrounds in disciplines like wrestling and jūjitsu. Even as it has grown, the emphasis of jūdō has remained on scoring a decisive ippon—a high standard that continues to draw people of every stripe to the sport.

Japan’s ongoing influence on jūdō culture has helped preserve the elegance of the sport. Kusakura, a century old manufacturer of martial art gear, has played a significant part in this by helping set the standards for jūdō uniforms worn by the world’s top competitors, a role it first took as the supplier of uniforms to the Japanese national team when jūdō made its Olympic debut at the 1964 Tokyo Games.

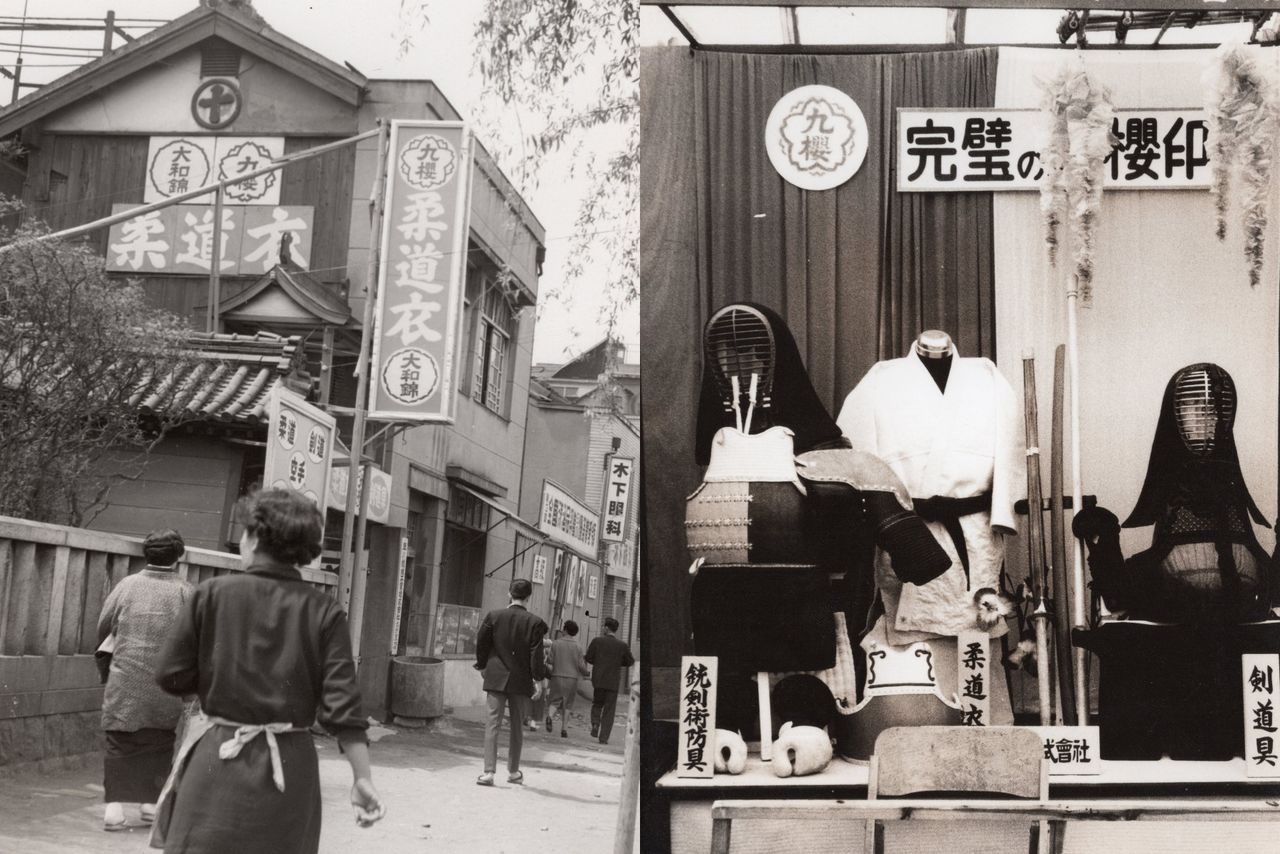

From left: The original Kusakura shop; an early display of equipment and uniforms for jūdō and other martial arts. (Courtesy Kusakura)

The lobby of Kusakura’s headquarters houses an exhibit featuring a uniform worn by jūdō’s founder Kanō Jigorō. (© Kumazaki Takashi)

Kusakura first opened for business in 1918 in Kashiwara, Osaka Prefecture. Miura Masahiko, its sixth-generation CEO, says the company grew out of the area’s long textile tradition that dates back to early modern times. When Miura’s grandfather started out making jūdō uniforms, he used specially woven sashiko-ori fabric made from locally produced Kawachi cotton.

Sashiko-ori is a traditional method of weaving that reinforces fabric by incorporating stitched strands into the material, producing a warm and durable cloth. Along with these practical functions, it developed as a decorative technique for embellishing textiles. Miura’s grandfather was to the first to recognize that the strength of sashiko-ori lent it to use in jūdō uniforms, which must be sturdy enough to withstand the rugged demands of the sport. Today it remains the standard fabric in use.

As Kusakura grew, it expanded its offerings to include uniforms and equipment for other martial arts. It also began weaving its own fabric. The early postwar years while Japan was occupied brought a drop in demand due to GHQ prohibiting martial arts training in schools. To survive, the company turned to making work trousers. Once the ban was lifted, though, Kusakura quickly resumed production of jūdō wear and saw its business grow.

Since then, the company has leveraged its dedicated manufacturing approach to help lead the way in improving the quality of jūdō uniforms. For instance, it was the first to succeed in creating a bleached fabric as well as to fully mechanize all aspects of the weaving process. It also contributed to the adoption of blue jūdō uniforms.

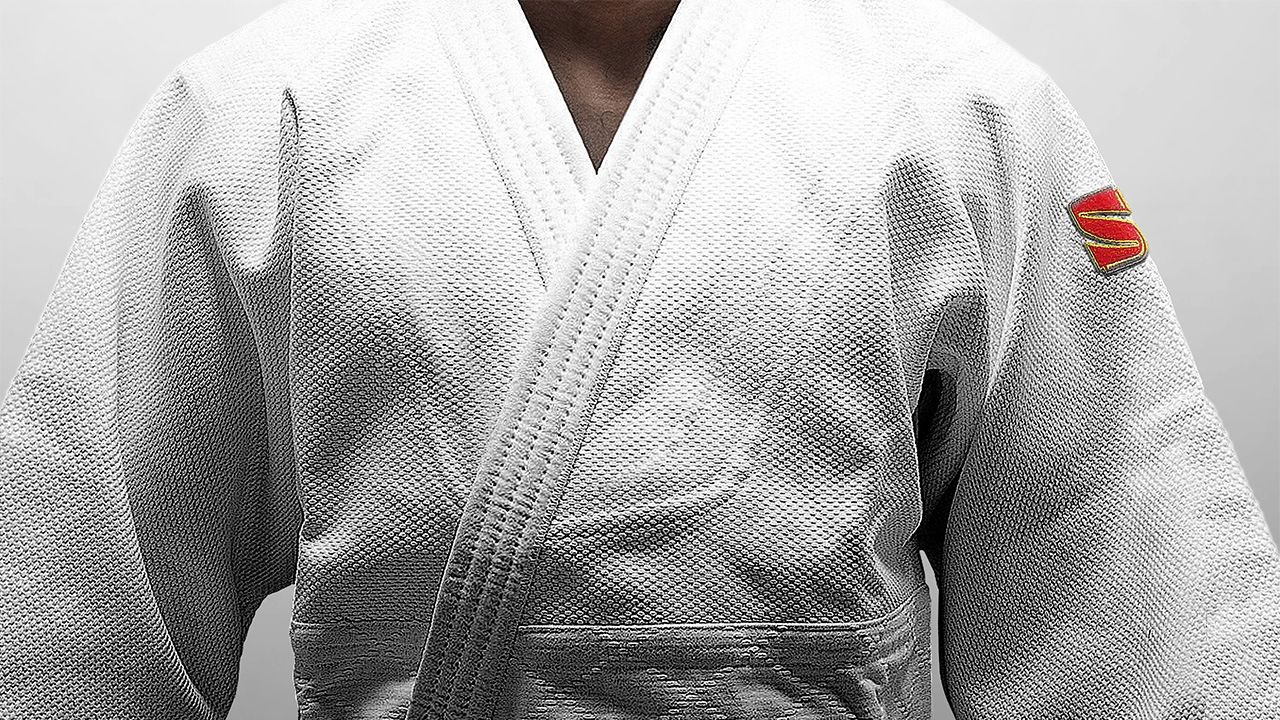

Kusakura’s uniforms, which sell for around ¥30,000, are certified by both Japanese and international jūdō governing bodies. (Courtesy Kusakura)

Establishing Competitive Standards

For much of the history of jūdō, there were few regulations governing uniforms. As the level of the sport increased, a passive strategy began to emerge whereby competitors at major international tournaments would aim to bring matches to a decision. To aid in this, some participants took to wearing jackets with stiffened collars or narrowed sleeves that hampered an opponent’s ability to get a good hold, lowering the likelihood of scoring a decisive ippon victory. Such outfits were made cheaply and were of lower quality than Japanese-made uniforms, raising concerns that their expanding use might fundamentally change jūdō.

In response, the International Jūdō Federation in 2014 moved to establish clear rules for uniforms to assure the fairness and integrity of matches. Miura says that the IJF conferred with Kusakura about the changes and even used its uniforms as a model. The firm continues its advisory role. “We’ve been involved in subsequent revisions ahead of each Olympics,” explains Miura.

The new rules set such specifications as the width of the collar when folded, an assurance that the fabric was not overly stiff, and the weight and strength of material per square meter. The heavy all-cotton fabric typically used was swapped for a blend of 70% cotton and 30% polyester to make uniforms lighter while retaining strength.

Each of Kusakura’s uniforms are carefully hand-sewn. (© Kumazaki Takashi)

There are currently 15 sportswear makers certified by the IJF. While Kusakura’s output is modest compared to some of the larger manufacturers on the list, which includes a number of global brands, its long history as a dedicated maker of jūdō uniform assures it a rock-solid reputation.

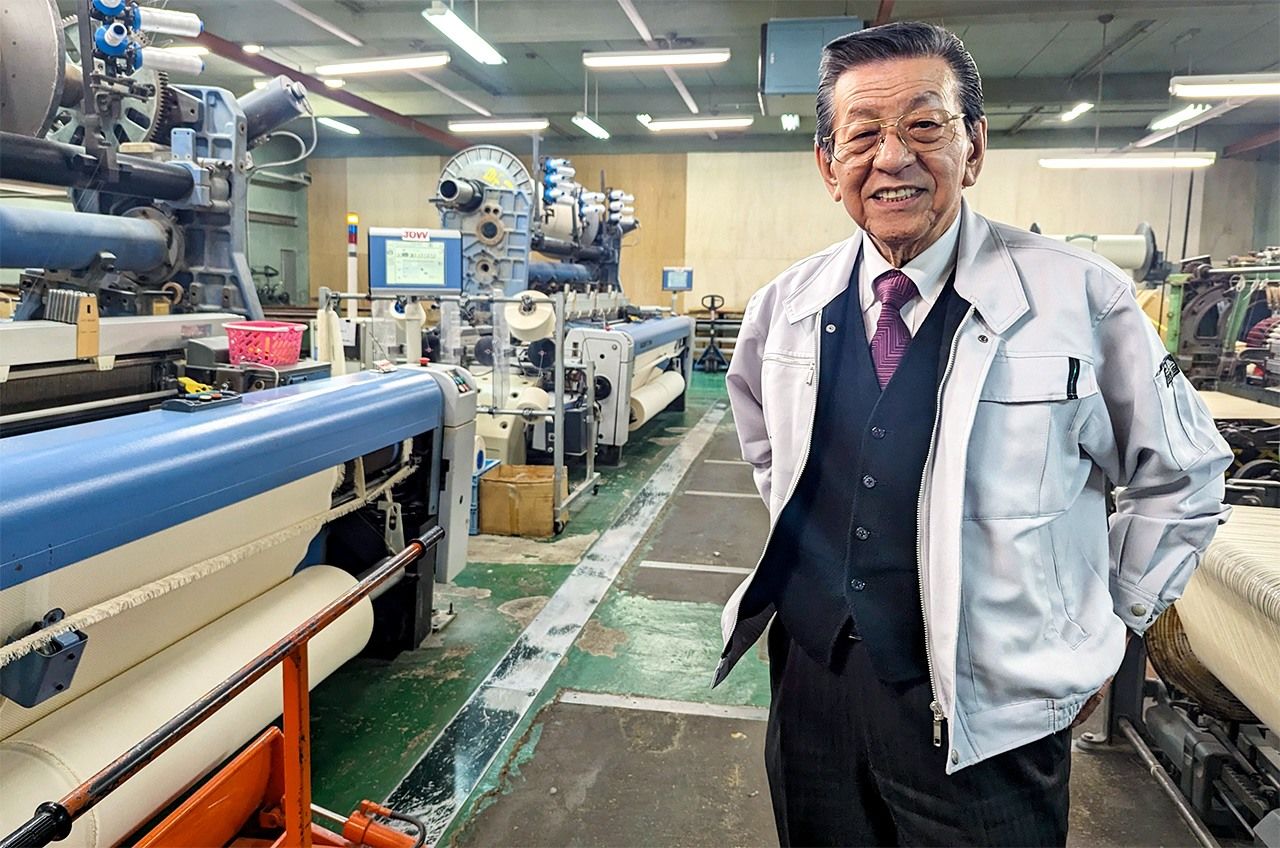

Many companies outsource production overseas, something that Kusakura also does for its uniforms produced for school physical education programs. However, when it comes to competition jūdō uniforms, Kusakura works solely in-house. “From weaving fabric to sewing the final stitch, we’re the only company on the planet that does everything ourselves,” Miura declares.

High-Quality Craftsmanship

Making a jūdō uniform is an intricate, multi-stepped process. The investment and expertise involved is a barrier to entering the niche market and is also why many firms offshore their production. In this respect, Kusakura’s long history gives it an advantage. “Jūdō uniforms have a reputation for being stiff and bulky,” explains Miura. “But we’re able to control the quality by weaving our own fabric to produce outfits that are light and comfortable.” Each step, from cutting to sewing, is done by hand by experienced craftsmen, who use feedback from customers to ensure a tailored-made feel.

Miura admits that Kusakura faces challenges in the forms of rising material costs and its aging workforce of artisans. “Young people aren’t interested in joining the textile industry,” he laments. “We have training programs aimed at passing down the skills and know-how built over generations, but it’s an uphill battle.” He notes that the company’s concerns also extend to its aging machinery. For instance, the loom the firm relies on to weave its fabric is no longer in production, meaning that spare parts are in short supply. “If something breaks, the operator has to fabricate a replacement by hand.”

Despite these hurdles, Kusakura maintains an unwavering commitment to quality. Its products may be more expensive than many others on the market, but their excellence ensures that they remain the choice of top jūdōka.

Miura Masahiko on the Kusakura factory floor. (© Kumazaki Takashi)

Many of the leading sportswear brands have agreements with jūdō unions to supply uniforms for major competitions, meaning that athletes from many countries have to wear gear provided by sponsors. This puts a small operator like Kusakura at a disadvantage, but Miura insists the company is undaunted by its larger rivals. “At the 2014 games in Rio de Janeiro, eleven of the fifty-six medalists wore our uniforms,” he proclaims. “That put us in a tie for second. We may be small, but it shows we can hold our own against the bigger brands.”

Kusakura has traditionally focused on the domestic Japanese market. Faced with bleak prospects for growth due to the country’s shrinking population, it is now looking to expand its market share overseas. “We traveled to the world championships in Brazil in 2013 and made the rounds to draw attention to our uniforms,” explains Miura. “We spent the entire time meeting with federation members of different countries and visiting dōjōs in Rio and Sau Paulo.” Although it took time to build up its reputation, Kusakura’s persistence bore fruit in 2022 when it inked a contract with the Brazilian national team. “Brazil has a large population of people of Japanese descent. This has helped it develop into a major jūdō nation, on par with France. In fact, the jūdō population there is said to be the largest in the world.”

As it works to extend its reputation within the world of jūdō, Kusakura, with its century of experience and ongoing dedication to quality, remains positioned to guide the sport as it continues to develop and evolve.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A hand-sewn Kusakura jūdō uniform. Courtesy of Kusakura.)