Japanese Agriculture for a New Era

Haliyo Kaki Vinegar: Letting Nothing Go to Waste

Science Culture Environment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Bringing Neglected Orchards Back to Life

When you order a vegetable curry or stewed pork combo at the stylish café-restaurant inside the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum in Ebisu, Tokyo, your meal arrives with a small medicine bottle with a pipette, containing a special kind of vinegar made from the Asian persimmon, or kaki.

Like any vinegar, kaki-su has a sharp bite, both in aroma and flavor. But add just a few droplets to a dish, and the sting of the acidity subsides. The vinegar has an extraordinary ability to bring out the subtle flavors of the ingredients, broadening the harmony and the satisfying umami of the dish. The effect is so dramatic it’s almost as if you’ve sprinkled magic dust on your food.

Haliyo Kaki Vinegar is produced by Rivercresc, a small artisanal producer based in Kaizu, Gifu Prefecture. The small city is located west of Nagoya, in the narrow space between the three Kiso rivers (the Kiso, the Nagara, and the Ibi), where the Nōbi Plain meets the Yōrō Mountains to the west. “The area is famous for its delicious fresh water,” says the company’s representative Itō Yuki with pride. “The rainwater that falls in the mountains flows underground and bubbles to the surface around here as springs and streams.”

The clear waters of the Tsuyagawa (a tributary of the Ibi River). Itō’s affection for the local rivers is reflected in the name of her company, Rivercresc (from crescendo). (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

At the mention of a vinegar made from persimmons, many readers will perhaps imagine a long-established family firm that has been crafting vinegar according to the same time-honored recipe for generations. In fact, Haliyo Kaki Vinegar is a new product that Itō conceived on her own (although somewhat similar vinegars are made from persimmons on an industrial basis in Wakayama, Yamagata, and several other prefectures). What made her decide to launch a craft vinegar in this style now? The story goes back to the persimmon orchard that her grandfather once ran close to the site of the current factory.

Itō was born in the small rural farming town of Nannō, which became a part of Kaizu following municipal reorganization. She always enjoyed science in school and loved carrying out her own experiments. She went on to study chemistry at Nagoya University. After completing graduate school, she was hired by a major communications company in Tokyo and later moved to an IT consulting firm. In 2007, she left to establish her own consultancy. During a project to regenerate rice terraces in Okayama and bring new energy and young people into local communities, she realized that the area where she had grown up faced many of the same problems as other rural towns throughout Japan: an aging population, a lack of people ready or willing to take continue local businesses into the next generation, and as a consequence, increasing areas of arable land being abandoned and lost to cultivation.

“Kaizu has a long history as a major producer of fuyū-gaki, one of the most important varieties of kaki, but everywhere you looked, the persimmons were ripening and falling from the trees or just being left for the birds to eat. It seemed such a waste.”

Itō had the idea of processing some of this fruit into a product that might help to inject a little cash and vitality into the community, and decided to visit her grandfather’s old persimmon orchards, long since abandoned and allowed to grow wild. She found a place choked with thick weeds that made her hesitant even to enter what had once been a well-maintained orchard. She decided to wait until the winter, when the worst of the weeds would be killed off by the colder weather. She sent in a team to cut back the thick growth of grass and restore order to the plot, then carried out trimming and maintenance on the surviving persimmon trees.

Experimenting to Get the Right Method

Whenever she could spare time from work in Tokyo, Itō returned to Kaizu and started looking for ways to make use of the persimmons going to waste. Interest in fermented foods and fruit vinegars was just starting to grow at this time, as part of the health food boom. Itō decided to focus on persimmon vinegar, and set about teaching herself the rudiments of fermentation, reading all the books and online resources she could find and drawing on her scientific background and love of experiments.

The sight of persimmons ripening on the boughs is part of the rural scenery in many areas of Japan. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

A small deer put in an appearance during our visit. Keeping out animal visitors is a never-ending challenge for cultivators in areas with dwindling human populations. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

After four years of trial and error—trying out different ways of cutting the persimmons, adjusting the temperature during the fermentation process—Itō had refined her production process. By then, her grandfather’s old persimmon trees had started to produce fruit again, but the yield was still too small to make commercial-scale fermentation feasible.

In 2016, Itō shifted her base to Kaizu and decided to concentrate on vinegar-making full time. The first step was to draw up a business plan.

“It wasn’t primarily about applying for financing. My main motivation was to use the business plan to get a fresh look and see my idea more objectively.”

During her time in consulting, Itō had often helped clients write up business plans, and was able to put this experience to use now in starting her own company.

In fact, Itō admits that there was another reason behind her decision to return to her hometown.

“I was starting to feel that there were limits to what I could achieve in consulting. Although I could advise clients on how to run their businesses companies, my guidance wasn’t based on real-life experience and it always felt less than fully convincing.”

She was starting to feel that you needed to experience something yourself before you were in a position to advise other people.

Making the Most of Surplus Fruit

For her raw materials, she approached the persimmon division of the local agriculture cooperative and asked them to give her fruit that didn’t pass the strict inspection criteria allowing the produce to be offered for sale as food.

“The harvest season for persimmons is short, and a lot of farmers bring their produce to the evaluation centers at the same time. Often perfectly good fruit goes to waste because it gets damaged or goes bad before it can go to market, while the producers are still waiting for the results of the evaluations. Until we stepped in, this fruit was just going to waste: you would see piles of it lying around in the back of the warehouse, just waiting to be thrown away.”

Itō’s persimmon vinegar is produced made using an extremely natural and simple process: the fruit is fermented using yeast found naturally on the skin of the fruit, and the fermentation broth, or moromi, is strained and then left to slowly turn to vinegar under a thin film of opaque cellulose produced the surface of the liquid by naturally occurring acetic acid bacteria. This totally natural, traditional method has been used to make vinegars for centuries. It uses no added ingredients—and doesn’t even require the addition of water or the use of heat.

During the trial stage, Itō started the fermentation process in early December, and the vinegar was ready by the end of March. But when she started production for real, the large five-ton capacity tanks she used meant that the fermentation process took longer, so that it was September by the time her first batch of finished vinegar was completed and ready. “The feeling when I tasted my own vinegar for the first time was a huge surge of relief,” Itō says now, looking back on those nervous early days.

By the entrance to the fermenting shed. The building was originally used as a warehouse, and when Itō first rented it, had no running water or electricity, and no toilet facilities. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

Persimmons waiting to be processed (left). To the untutored eye, it’s not easy to see why these specimens failed the selection process. (© Ukita Yasuyuki) At right, local women processing the persimmons. Area farmers help out during harvest and at other busy times of year. (© Itō Yuki)

Persimmon vinegar in the fermentation tanks. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

A thin film of acetic acid can be seen on top of the developing vinegar. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

When she sent the finished vinegar to the Japan Food Research Laboratories for analysis, the results showed that the persimmon vinegar contained five times as many amino acids as pure rice vinegar.

Itō tapped her contacts from her days in Tokyo and hired a famous well-known designer for the packaging and branding. She chose the chunky bottle with its hefty feel herself.

The striking packaging for Haliyo Kaki Vinegar. Every bottle displays the year of production, since different “vintages” vary subtly in flavor. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

The Haliyo brand name comes from hariyo, the Japanese word for the smallhead stickleback, a species of freshwater fish that lives in Kaizu.

The fish needs fresh, pure water to survive, and is designated as critically endangered by the Ministry of the Environment. In Kaizu, the local authorities are working to conserve the local populations, and the population of fish in a lake fed by the Tsuya River have been designated as a natural monument, with its habitat protected by the national government. The brand name reflects Itō’s determination to promote the natural beauty of the area and protect it for the future.

She also chose to use the Japanese word kaki for the English branding rather than the English term “persimmon.” The Japanese word is already familiar in many European languages, and is also used as the botanical name for the species. Itō hopes that one day “kaki vinegar” will become well known internationally as a Japanese product, as has happened with “sake” and other terms from Japanese culinary culture.

At left, kaki vinegar aging in jars. Itō wants to see if her vinegar becomes more valuable after aging, like balsamic vinegar from Modena, Italy. At right, a sauternes barrel, used in Itō’s cask-finishing series to impart hints of the “noble rot” flavors of this famous sweet wine from Bordeaux. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

Once the product was ready, Itō had to think about how to sell it. She had no previous retail experience, but started by selling her product at the local michi no eki produce shop and similar outlets, as well as at a “farmers’ market” in the Aoyama district of Tokyo. Steadily, more people became aware of kaki vinegar. The product gained rave reviews and word began to spread about this remarkable natural product with its uncanny ability to bring out the flavors of ingredients. Steadily, Haliyo Kaki Vinegar built a reputation, largely by word of mouth, and a number of noted Japanese restaurants in Tokyo started using the product. Today, she has three main distribution channels, each accounting for about a third of total revenue: online sales, sales to restaurants, and sales at shops including michi no eki.

Tasting the vinegar. The pipette is a reminder of Itō’s chemistry background. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

Some of the kaki vinegar is “finished” in casks previously used to age wine, whisky, and other beverages. From left: French oak, sherry, bourbon, and sauternes. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

Creating the Perfect Circular Economy Business Model

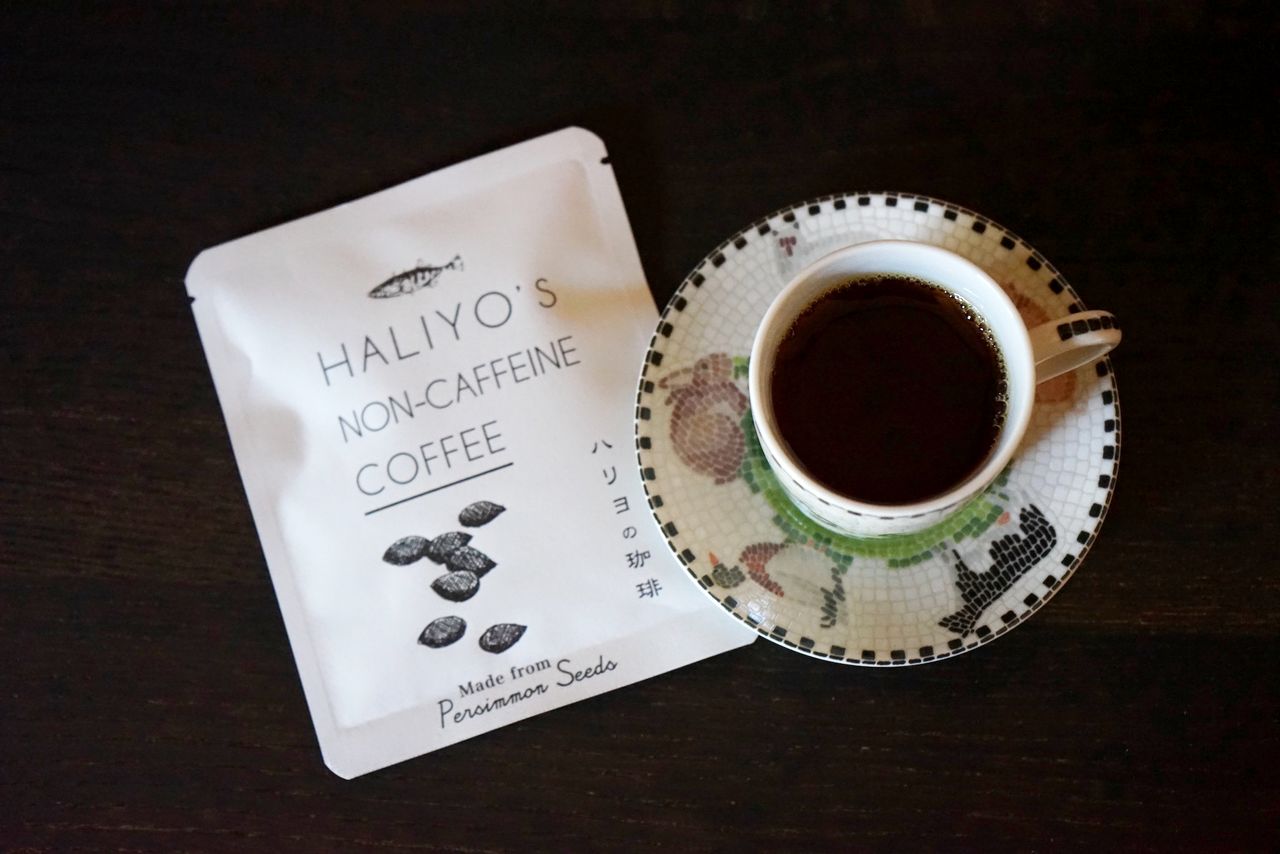

Since a large part of the inspiration for Itō’s company was to make use of fruit that was going to waste, it is perhaps not surprising that she is eager to do everything she can to reduce waste from vinegar production. One idea was to ask local coffee roasters to roast the persimmon seeds, producing a unique caffeine-free “coffee” available nowhere else.

The lees left over after the moromi has been filtered are rich in nutrients, and are used as fertilizer and as feed at a local quail farm. They are also used as one of the ingredients in a retort curry flavored with kaki vinegar. Twigs and other scraps of wood left over after tree-trimming and thinning are processed into cutting boards and lampshades. Everything at Itō’s company embodies the ideals of the circular economy: Nothing goes to waste.

“Coffee” made from persimmon seeds. The drink has a pleasant depth of flavor to balance out the coffeelike bitterness. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

Haliyo Curry: a pork vindaloo, with kaki vinegar. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

A cutting board and spoons made from processed persimmon wood. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

A lampshade made from persimmon wood, on sale at the factory shop in Kaizu. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

One thing she has been focusing on in recent years is trying to revive the popularity of the yōhō variety of persimmons. This hybrid of the fuyū-gaki and jirō-gaki varieties has a darker color and a pronounced sweet flavor. Yōhō was registered as a recognized variety in 1991, but the volume being harvested and brought to market has fallen in recent years, making it something of an elusive variety. Itō dreams of a day when it will develop into a local specialty to rival fuyū-gaki in popularity.

Itō is working to make the yōhō variety more widely available again. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

At the end of 2023, Itō put the finishing touches to the latest batch of kaki vinegar—the eighth time she has personally overseen the brewing and maturation process. Itō is now able to use a small sample from the previous year’s batch as a starter, making the fermentation process more stable. She has also kept back part of earlier batches for aging, and says she is looking forward to seeing how maturation and finishing affect the flavor of the vinegar.

During the first year, Itō was so stressed about whether she would have a usable product that she started to lose her hair. “Things are much more relaxed now,” she says with a smile. (© Ukita Yasuyuki)

What does the future hold for Itō and her project?

“I’d like to expand our distribution and sales channels. But for me it’s not about moving to mass production and selling as much as possible. My ambition is to place the product in high-quality settings. My dream is for kaki vinegar to become more widely known around the country and further afield, and to associate Kaizu in people’s minds with delicious, high-quality persimmon products. Maybe one day people visiting Japan from other countries will seek out Kaizu to see where the persimmons and the vinegar come from.”

Although part of the original inspiration of the project was to contribute to the local area community, Itō now says modestly that this is almost a side effect. “Since we use local persimmons, I suppose we do contribute to the community to a certain extent, but really that’s not the focus anymore.

“To tell you the truth, my real dream—I’m only half serious when I say this, but I really love traveling to Spain. They often have kaki in the markets there, and I sometimes think how great it would be if one day I could produce a kaki vinegar there too. That would really be a dream come true . . . ”

The mission to spread the word overseas has already started to bear fruit, and Itō recently received an order from a buyer in Singapore. The future looks bright for this small company and its owner’s efforts to bring a distinctly Japanese touch of vinegary magic to dishes around the world.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Itō Yuki in her persimmon orchard. © Ukita Yasuyuki.)