Increasingly Isolated in Japan

A New Approach to Tackling Poverty: The Grown-Ups’ Cafeteria Program

Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Enjoying the Companionship of a Shared Meal

The eighth “grown-ups’ cafeteria” session takes place in a large room on the ninth floor of the Sendai City Welfare Plaza. The otona shokudō, a twist on the kodomo shokudō (children’s cafeteria) programs that are common around the country, this event is for employed and unemployed workers, ages 18 to 65, and their families. Along with a free meal, participants can get free legal advice from lawyers attending the event. The flyer says, “Come join us. Tell us your gripes about work and life.” When the doors open at 6:00 in the evening there is already a line of about a dozen people. By the time everyone takes a seat, the number has grown to 30. Most are men, but there do seem to be a few women. One or two union staff members sit at each of eight tables, exchanging pleasantries with the people at their table as food is served. Today’s menu is spaghetti with tomato sauce and Japanese yam soup. The room fills with chatter as people begin to eat.

The day’s menu: spaghetti with tomato sauce and creamy Japanese yam soup.

One young woman, a part-time worker, has been attending these dinners since they first started. The first time, she didn’t really grasp what it was all about, but then she got to know one of the young volunteers and started to enjoy herself. Why does she keep coming? “It’s a lot more enjoyable than eating all by yourself,” she says. “The food tastes so much better.”

A man in his fifties sitting at another table explains that he came to Sendai after losing his job in Yamagata Prefecture. He was unemployed at the time of the last otona shokudō but says he has been working since the end of September as a dispatch agency employee at a nursing home. He spent ¥10,000 of his first paycheck to buy a suit, and today is wearing a coat that he bought cheap from a friend. Until now, he had only a few pairs of jeans. He’s got a job at last, but next month he’ll be on call for only a few shifts, and his salary will drop to around ¥70,000. “I’m a homeless person with a suit,” he says with irony, but continues, “There’s a lot of love here and I get to be with other people. The young folks, especially, make me feel alive again.”

This man, now in his fifties, is concerned about his erratic shifts at work.

Creating a Community Space for Workers

What is the grown-ups’ cafeteria all about? We asked Mori Shinsei, a representative of the Sendai Keyaki Union, to explain why the labor union operates this program.

“There’s a volunteer group called the Sendai Yomawari Group helping the homeless in Sendai. They provide hot meals at various locations for people who’ve lost their jobs because they were fired or became too sick to work. Once you are homeless and unemployed, it’s really hard to get back on your feet. People need help before things get that bad. But impoverished people who still have a place to live rarely ask for help. That’s why we decided to focus on the working poor and provide them with a place where they can get together. That was how the otona shokudō got started.”

The cafeteria program is held once a month. Only three people came to the first dinner, but the numbers have slowly increased since then, with 13 at the second gathering and an average of 10 or so thereafter. At the seventh otona shokudō, there were 25 participants, a sudden increase due in part to the appearance of a group of homeless people.

“When a group like that walks in, other people are likely to balk at joining them,” says Mori. “To overcome the stigma, we are using larger rooms and breaking up the homeless group, so their presence is not so obvious. The problem is, there really isn’t any difference between those of us who happen to have jobs at the moment and those who don’t and are homeless. There’s no special category or type of person that becomes homeless. According to a survey by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, there were around 5,000 homeless people in Japan in January 2019. But I think the real number is in the tens of thousands. You may be in the workforce right now, but there’s no telling when you will find yourself without a job or a roof over your head. We shouldn’t be pushing these people away. Instead, we should be trying to solve the problems that got them there in the first place.”

As it happened, there was a group of homeless people at the eighth otona shokudō too. “These people may come across as a bit scruffy and brusque, but that’s because they have been mistreated and abused,” explains Mori. “One of them had a liquid poured into his ear while he was sleeping, causing permanent hearing damage. It’s no wonder they are sensitive to discrimination. Even here, they may complain that other people are being served first and that it is because of their homelessness. But it has nothing to do with who they are. We will never shut these people out.”

Low Pay, No Bonuses, No Career Advancement Opportunities

Sendai Keyaki Union representative Mori Shinsei.

There are many other kinds of people who come to the grown-ups’ cafeteria. Temporary employees, the unemployed, and even a few people who have the good fortune to be regularly employed. But these last are what Mori calls “marginal” employees, trapped in “black” companies that exploit their workers. Their pay is low, they get no bonuses, and they are shut out of career advancement opportunities.

“A woman came to us for counseling,” recount Mori. “She had a mild psychiatric disorder and couldn’t work. She said she wasn’t able to feed her children. At first, I thought she was a single mother, but as we talked I realized that there was a husband living with her. He ran a well-known tutoring service for schoolchildren. It was hard to imagine how the family could be poor. But then we learned the tutoring service was a franchise. He had about 250,000 yen in income per month, but out of that he had to pay royalties to the head office, plus the rent and utility bills for a classroom. That left only 70,000 yen for the whole family to live on. There are a lot of cases like this. We can’t solve the problem of child poverty if we don’t first do something about adult poverty.”

It’s impressive to say you own a business, or are self-employed, but people like this who are tied up in a contract with a big franchise are just laborers, self-employed in name only.

Freeing People From “It’s Your Own Fault”

“A lot of the people who come to the otona shokudō are clearly feeling insecure. Those that work for dispatch agencies, for example, worry that their contracts are only temporary, and they don’t know what to do next,” says Mori. Even so, only a handful actually ask for advice about employment.

“I can think of three reasons why this is so. One, they’ve already sought advice from various offices and agencies, and have been discouraged by the response. Advisors at the local labor standards office, for example, will warn them that they will get in trouble if their company learns they are seeking help, or the local labor union will just shake its collective head and say that their case is ‘difficult.’ So, these people give up. Second, pay rates in Japan are low and social security is inadequate. That leaves a lot of people thinking there’s nothing that can be done until they hit rock bottom and are actually starving. They are totally brainwashed to think it is all their own fault. Third, they fear they will be criticized for accepting any kind of welfare. People can also be suspicious of labor unions. It’s not uncommon for labor union staff to be accused of cheating and using collected dues for their own personal benefit.”

From Receiving to Giving

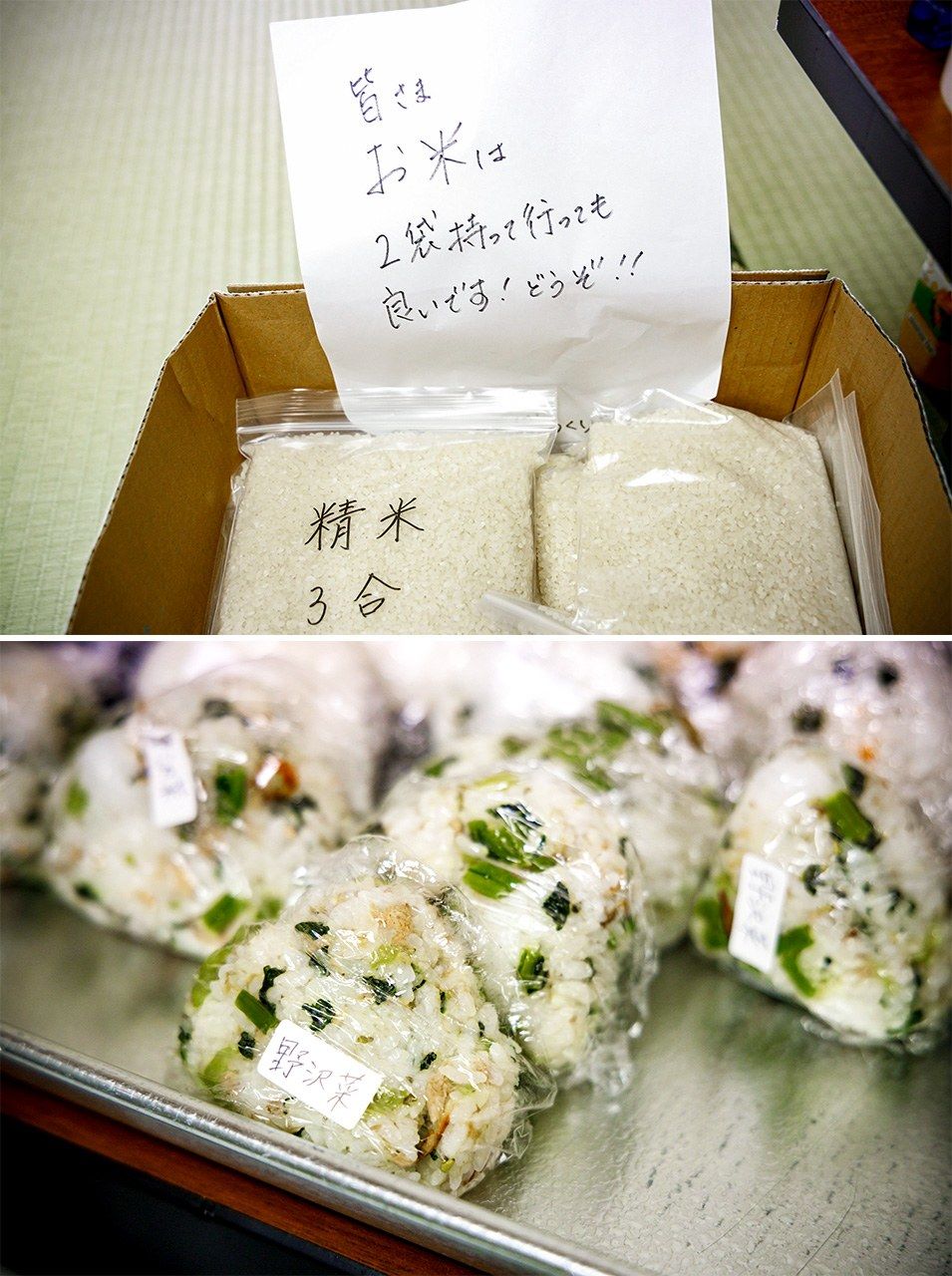

Bags of rice and homemade rice balls set out for cafeteria diners to take home.

Do people making use of welfare services take it all for granted? No, says Mori. At the otona shokudō there are some who are trying to give back a little of the help they have received.

“See that fortyish woman over there? She had only 1,200 yen to her name and was contemplating suicide when she came to us. We arranged for her to get welfare payments and she decided to live. Now, she wants to repay us by working as one of our volunteers.”

Another former participant, a man also in his forties, is volunteering for the first time at the cafeteria. He’s a hard worker, though it is all still very new to him, eagerly asking people if they would like some tea and bringing it to them. He had been keeping to himself after a doctor told him he shouldn’t be working, but was feeling overwhelmed by loneliness. He found the program on the internet and started coming to the dinners in September.

“I hesitated at first,” says the man. “Wasn’t sure if I should go in. But the young college student volunteers were working hard to make people comfortable. I really enjoyed it. Since then I’ve been looking forward to this gathering every month. Now I want to return the favor. This is my first time to volunteer and I’ve been awkward. Not sure I have been much help,” he laughs shyly.

Building relationships of trust is the most important aspect of managing the otona shokudō program, says Mori.

“We’re not here to offer one-way support to people. We are here to share and help each other. The relationships of trust that we build here make it possible for us to give these people the kind of support they need and see that their rights are respected. We offer them a place where they can forge ties with others. Our program helps them to see that their circumstances are not all their own fault, and that it’s OK to accept help from other people.”

(Originally written in Japanese. Interview and text by Kuwahara Rika, Power News. Photos by Imamura Takuma. Banner photo: A woman diner talks with a volunteer graduate student.)