Legends: Japan’s Most Notable Names

Ueno Chizuko: Japan’s Feminist Icon Gaining International Recognition

People Society Culture Family Work- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A leader in Japanese women’s and gender studies for more than 40 years now, Ueno Chizuko has also become something of an international superstar in the past few years as a consequence of the surprisingly large following she has attracted in China.

Ueno Chizuko gives a speech at the University of Tokyo’s April 2019 matriculation ceremony. (© Kyōdō)

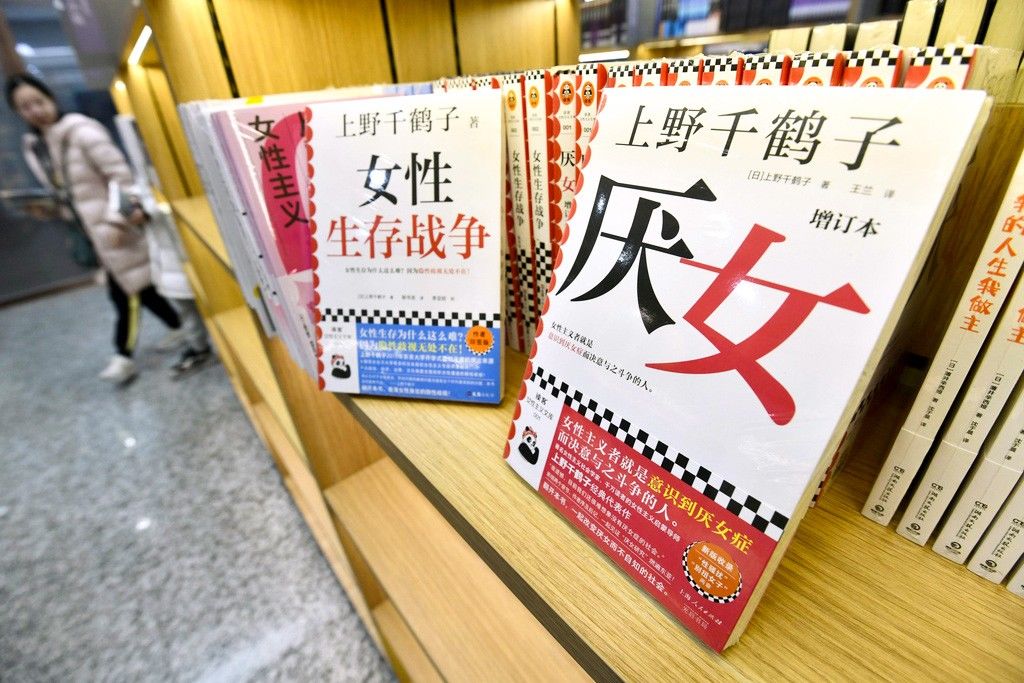

Chinese translations of Ueno Chizuko’s books in a Beijing bookstore in February 2024. (© Kyōdō)

China’s Ueno Chizuko boom was triggered by a fiery speech she gave at the University of Tokyo’s 2019 matriculation ceremony. Dispensing with the conventional bromides, Ueno challenged the students entering Japan’s most elite university to acknowledge their own privileged status, recognize gender discrimination and other injustices in academia and society at large, and use their position to help others less fortunate. A video of the speech subtitled in Chinese went viral, and translations of her books—more than 20 in all—began climbing up China’s bestseller lists. Explaining Ueno’s selection as one of Time magazine’s “100 most influential people of 2024,” Leta Hong Fincher wrote that she “has become a role model for millions of Chinese women quietly rebelling against pressure to marry and have babies.”

Avoiding the Marriage Trap

We asked Ueno what led her to reject marriage and family life.

“I grew up in a three-generation household in the Hokuriku region,” she said. “My father was a tyrannical husband, and to make matters worse, he was a mama’s boy. He spoiled me, but it was a kind of discrimination. He insisted that his sons follow a rigid educational and career path, but he had no expectations at all for his daughter. To him, I was basically a beloved pet.

“My parents married for love, but my mother reproached herself for her poor taste in men. At some point when I was in my teens, I looked at my mother and thought, ‘You know, Mom, even if you were married to someone else, you’d still be unhappy.’ Ordinary, fine, upstanding men and women enter into the institution of marriage, and the outcome is unhappiness. I realized that that was a problem rooted in the structure of patriarchal society, and it couldn’t be solved by a better choice of spouse. So, I resolved to avoid the trap of marriage, and that’s how I’ve lived my life.”

In 1967, Ueno enrolled in the Kyoto University Faculty of Letters, where she majored in sociology. That was just before the outbreak of the nationwide student protest movement, and Ueno took part in the occupation of campus buildings and the demonstrations against the Vietnam War. But she eventually became disillusioned with the traditional gender roles and biases that remained firmly entrenched “behind the barricades.”

“Men of my generation, the baby-boomers, were liberals in their heads, but from the neck down, they were mired in the patriarchy. I can’t tell you how many bitter memories I have of the things they said and did to me back then.”

Embracing Women’s Studies

Those experiences, combined with Ueno’s determination not to turn out like her mother, laid the foundation for her feminism and her embrace of women’s studies. She was a graduate student in sociology when she first came in contact with the new field. Originating in the United States against the backdrop of the women’s liberation movement, it was a discipline “by women and for women.” The idea that people like herself could be the subject of academic study was a revelation for Ueno, and she threw herself into the field, emerging as one of the founders of women’s studies in Japan.

During the late 1960s and 1970s, women’s liberation movements had broken out almost simultaneously in countries around the world. In Japan, a major catalyst was women’s disillusionment with the student protest movement. One of the leading figures of women’s lib in Japan was Tanaka Mitsu, who died on August 7 this year at the age of 81. Tanaka called for women to free themselves from motherhood and sexual exploitation, and she helped defeat legislation that would have excluded “economic reasons” as a justification for abortion, arguing that it was a “woman’s right to bear children or not to bear children.”

In 1975, when the First World Conference on Women was convened in Mexico City to coincide with International Women’s Year, Japanese women’s organizations joined forces and launched a nationwide campaign against gender discrimination.

“That was when the term feminism gained currency and emerged as a national policy issue in countries around the world, including Japan.”

Settling for “Equal Opportunity”

In 1985, Japan passed the Equal Employment Opportunity Act in order to align its laws with the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, which it ratified the same year.

“The law was thrown together and rushed through with a view to getting the treaty ratified,” says Ueno. “Women’s groups were originally campaigning for an equal employment act, but the government switched in an ‘equal opportunity act.’ The idea was, ‘We’ll give you the opportunity to compete on a level playing field with men, and it’s up to you to fight and win on that basis.’ The law forced us to relinquish statutory protections for working women and ignored the entire issue of how men work.

“The equal opportunity act made it possible for management to maintain the status quo simply by dividing hires into two different tracks, sōgōshoku [management candidates] and ippanshoku [primarily support services]. Sōgōshoku included a few token women, while ippanshoku consisted entirely of women. The debate among the male executives at that time was centered on whether sōgōshoku women should be excused from tea-serving duties and whether they should be made to wear uniforms like the other women.

“My gut reaction was, ‘Is this what feminism is about? Clawing our way into the ranks of sōgōshoku just so that we can struggle to stay above water? That can’t be right.’ That’s when I came to see that the point of feminism wasn’t that women should behave like men and the vulnerable should become the powerful. It was that society should respect the vulnerable for who they are.

“Women made huge sacrifices trying to work just like men under the equal opportunity act,” says Ueno. “It’s taken another forty years for Japan to start questioning the way men work and embark on work-style reform.”

Women Against Women

In the 1980s, many women with older children began seeking part-time work to supplement their husbands’ income. Labor market reforms, beginning with passage of the 1985 Worker Dispatch Act, opened the way for a rapid increase in the number of “nonregular” employees, the majority of whom were women.

“Sōgōshoku versus ippanshoku, regular versus nonregular . . . this division of women against women was a human-made disaster driven by politics.”

Emblematic of such differences was the “Agnes controversy” that erupted in 1987. The dispute was triggered by news that Agnes Chan, a popular singer and TV personality, was bringing her infant son along with her when she went to work in the TV studio. That elicited a backlash from Japanese career women, including writer Hayashi Mariko, who argued that women needed to keep their private lives out of the workplace in order to be treated as equals.

Ueno disagreed vehemently. It was easy enough for men to keep their personal and professional lives separate, she wrote, because their wives had total responsibility for child rearing and other domestic duties. Working mothers should not willingly bind themselves to the unwritten code of patriarchal society, she asserted.

The debate was a turning point for Ueno, who became a prolific writer, engaging in vigorous public discourse on the issues that mattered to her. In 1990, she published Kafuchōsei to shihonsei (Patriarchy and Capitalism), in which she made the case for treating housework as labor. At the time, the idea was dismissed not only by economists but also by some vocal Japanese homemakers, who maintained that housework and raising children were acts of love. But the concept of domestic chores as unpaid labor has since taken hold.

The Scourge of Neoliberalism

The Fourth World Conference on Women was held in Beijing in 1995. That event marked “the peak of the honeymoon between feminism and public administration,” according to Ueno.

“There were about 40,000 women from around the world gathered at the NGO forum [held in conjunction with the conference], and 6,000 of them were Japanese women. Most of those were grassroots activists that local governments had sent to Beijing using public funds.”

But the honeymoon came to an end as public finances worsened following the collapse of the 1980s bubble. At the same time, the rise of neoliberalism, with its emphasis on free market competition, ushered in a raft of regulatory reforms and cutbacks in government services. Women’s rights were treated as a matter of personal choice and personal responsibility, an approach consistent with the Equal Employment Opportunity Act.

“The market for nonregular labor was originally designed for married women who wanted to work part-time to supplement their husbands’ income, but as the economic slump continued and labor deregulation progressed, others entered that market out of necessity. They included unmarried women and single mothers, along with the many young people who were unable to secure regular employment after graduation on account of the corporate hiring freeze. Many of these people ended up stuck in a succession of temporary, freelance, and contract jobs, and that has led to growing economic inequality.”

Internalizing the Neoliberal Values

Meanwhile, the percentage of Japanese women with a college degree has been rising rapidly since the 1990s.

“The main reasons are that people are having fewer children, and parents are more willing to invest in a daughter’s education than in the past. Today we have a substantial group of young women who are putting themselves first instead of prioritizing husband and children, which is wonderful.

“At the same time, a lot of young people have internalized neoliberal values over the past fifteen years or so. They’ve been made to believe that any hardships or misfortunes they experience are their own responsibility, so they don’t feel they can ask for help. They don’t want to admit weakness. This is especially noticeable among the educational elite. There’s a troubling increase in the incidence of self-harm on the University of Tokyo campus, and eating disorders are on the rise among the women. These winners of Japan’s entrance-exam competition are a bundle of anxiety.”

Amid all the emphasis on personal responsibility, many women reject financial assistance, no matter how difficult their circumstances.

“Today, six out of ten women employed outside the home are nonregular workers. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, many temps who were just scraping by stopped getting work altogether, and the problem of poverty among single women stepped out of the shadows. Even so, there were unemployed single mothers who refused to apply for public assistance. They’re not to blame for their situation, but they feel that it’s up to them to solve the problem.”

The Audacity of Activism

Economic inequality has continued to worsen over the past few decades. Year after year Japan ranks last among industrially developed countries in the Global Gender Gap Report published by the World Economic Forum. Is there any point in continuing the fight?

“People of my generation worked hard, yet we were unable to bring about the kind of social change we were fighting for. But some progress has been made. For example, it’s thanks to our struggle that victims of domestic violence and sexual harassment in Japan can now speak out and make themselves heard. Things will never improve if people do nothing.”

Ueno places her faith in the swelling ranks of young women who have rediscovered feminism and are putting themselves first. Ueno calls them the next generation of feminists—women who are following the example of the #MeToo movement and mobilizing social media to launch a variety of campaigns addressing women’s issues.

“In the end, the responsibility lies with all us adults who had the right to vote and allowed our politicians to perpetrate this human-made disaster. That said, social change doesn’t happen overnight. Someday the same young people who are asking who made the world the way it is are going to face the same question. That’s why I’m telling them that it’s their turn to carry on the struggle.”

(Originally written in Japanese by Kimie Itakura of Nippon.com. Banner photo: Ueno Chizuko, one of Time magazine’s “100 most influential people of 2024.” © Kyōdō.)

Related Tags

gender women Equal Employment Opportunity Act women’s rights gender gap