Legends: Japan’s Most Notable Names

Mysteries and Complexity: The Genius of Miyazaki Hayao

Society Culture Entertainment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Better Received Overseas

Miyazaki Hayao’s The Boy and the Heron was released in Japan in July 2023, a decade after his previous feature, The Wind Rises. But his return to theaters initially met with a mixed reaction.

Some Japanese viewers saw the film as difficult to understand. They felt the story too ambiguous, with many points left unexplained. Others saw it, however, as the director’s most freewheeling storytelling experiment to date, hailing the film’s movie expressiveness, its hand-drawn art, and its soaring imagination.

Even before its release, the film stood out as an outlier. Studio Ghibli eschewed outside investment, putting up the entire budget itself. This decision gave Miyazaki great freedom to work without the pressure of a fixed release date. Perhaps this helps explain the striking imagery and multilayered storyline of the finished product.

A strategy of secrecy surrounding the production generated buzz too. Studio Ghibli chose not to release a trailer or any imagery ahead of the film’s public release. There was no synopsis, description of characters, or even credits for the production staff. Instead, the studio released only a poster. This unusual tactic stirred interest in the lead-up to its release, while sparking lively discussions after.

The film did not perform as well as hoped at Japanese theaters, earning ¥9.3 billion (as of May 12, 2024, according to Kōgyō Tsūshinsha), leaving it short of the ¥10 billion domestic box office total every Miyazaki film has achieved since Princess Mononoke in 1997.

Instead, it was abroad that the film made real waves. It debuted in North America in December 2023, rocketing to the top of the opening weekend’s box office rankings—a rare feat for a foreign film in the United States. The final box office tally of $46.8 million (as of April 30, 2024, according to Box Office Mojo) was 2.5 times that of Ghibli’s previous bestselling film in North America, The Secret World of Arrietty (2012), directed by Yonebayashi Hiromasa.

The successes continued outside of North America. After the Chinese release of the film on April 3, it earned 770 million yuan (according to Maoyan Entertainment), the equivalent of ¥16 billion, in its first month. This made it a new record for Studio Ghibli—and the second-highest grossing Japanese film in Chinese history. The Boy and the Heron continued to be Miyazaki’s biggest hit to date in virtually every region except Japan.

It was also extremely well received critically. It became the first work not in English to win the Golden Globe for Best Animated Feature Film in January, and took the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature in March.

These triumphs were followed in May, when the Cannes Film Festival awarded an honorary Palme d’Or to Studio Ghibli in recognition of both Miyazaki Hayao and the late Takahata Isao’s achievements. It was no coincidence that this acclaim followed the release of The Boy and the Heron, and it represented a new pinnacle for both Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli in the international film world.

A Glorious Hand-Drawn World

Much of the attention surrounding the The Boy and the Heron may derive from the fact that it could well represent the 83-year-old director’s last full-length work. The rise of streaming services also played a role in the film’s international success. In 2020, Max (formerly HBO Max) began streaming Studio Ghibli’s films in North America, while Netflix did the same in other territories, broadening exposure to the films overseas.

But these points alone are not enough to explain its success. The reason fans all over the world love The Boy and the Heron is because it brims with Miyazaki’s singular style.

The quality of the hand-drawn 2D animation particularly captivated foreign audiences. This technique brings colorful parakeets taking flight, frogs swarming the main character’s body, and the world inside the crumbling tower to life, with a vividness that only traditional hand-drawn animation can provide.

The hero Mahito (above) and Birdman (below). (© 2023 Studio Ghibli)

Hand-drawn 2D animation requires tremendous skill on the part of the animators. It is painstaking work that takes a great deal of time. As part of the production process, nearly every scene in the film was penciled and painted by a handful of veteran animators, Miyazaki among them.

Today, 3D CG (computer graphics) technology is the mainstream for foreign feature animation. Even many films described as hand-drawn employ a great deal of computer processing for action and art, making it difficult to distinguish them from CG. In practice, much of the hand-drawn animation process has been lost.

The fact that Studio Ghibli continues to employ traditional animation techniques makes it an outlier in the industry. In fact, only two hand-drawn animated films have ever won the Academy Award for best animated feature—and both were Ghibli productions: Spirited Away in 2003, and now The Boy and the Heron in 2023.

The Power of Storytelling Gaps

One of the appeals of Miyazaki’s films is that they are structured differently from typical animated fare intended for children and their families. Feature films by Disney and Pixar tend towards the didactic, portraying parents and children as they “should” be. This focus on idealized worlds means even the best-made of them can often lack a certain depth.

Miyazaki’s work eschews one-dimensional educational values. Nor does it embrace a clear-cut distinction between good and evil. In The Boy and the Heron, the protagonist hits himself in the head with a stone to make it seem as though his classmates caused the injury. In another scene, he confesses that he has malice inside him. Each and every one of us has evil, or the potential for it, inside. The world is full of malice. How to face it? Miyazaki’s approach is not to teach but rather make the audience think. That gives depth to his work.

Takahata Isao, director of masterpieces including Grave of the Fireflies (1988) and The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013), plotted his films in a logical way. Miyazaki, on the other hand, develops his stories from visuals. This allows for unpredictable developments.

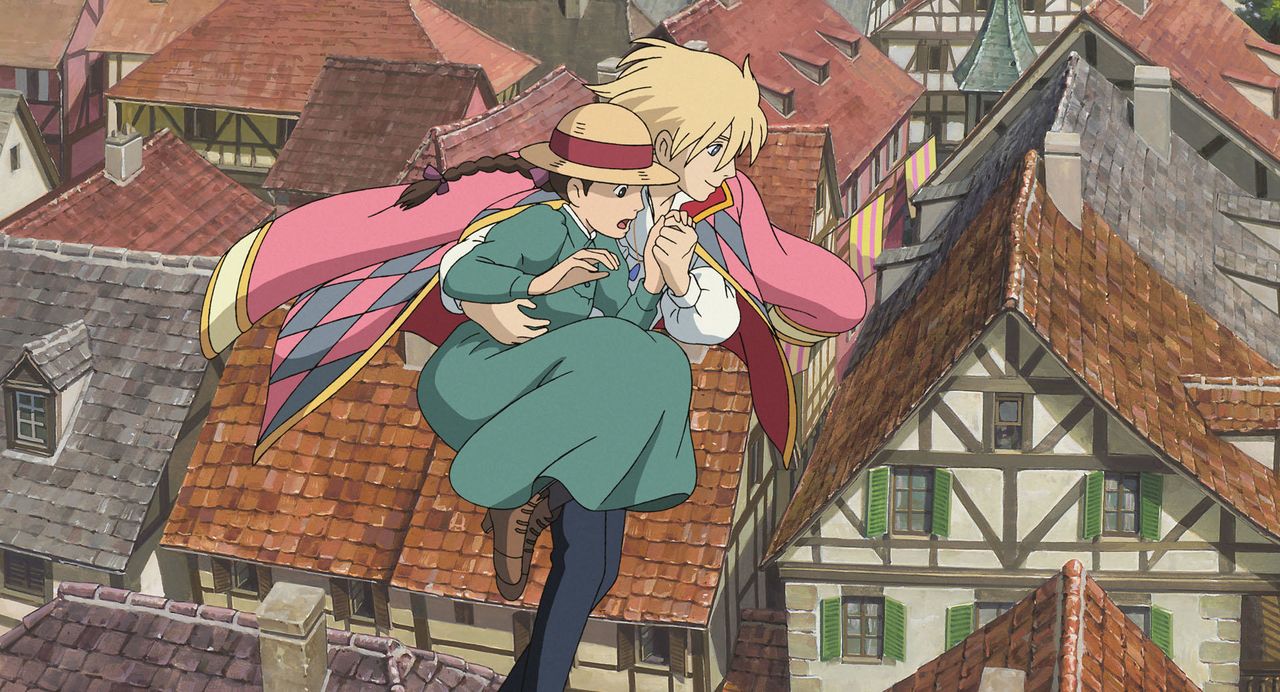

Miyazaki’s earlier works prioritized entertainment value. But from Porco Rosso (1992), he began to break away from the limitations of simple stories in favor of those with mysteries left unresolved. For instance, he never explains why the protagonist Porco turned into a pig. In Princess Mononoke (1997), viewers never learn if the curse inflicted upon the protagonist, which sets the entire story in motion, is ultimately lifted. Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) is set against the backdrop of a war between neighboring countries, yet hardly any details are given about the other side.

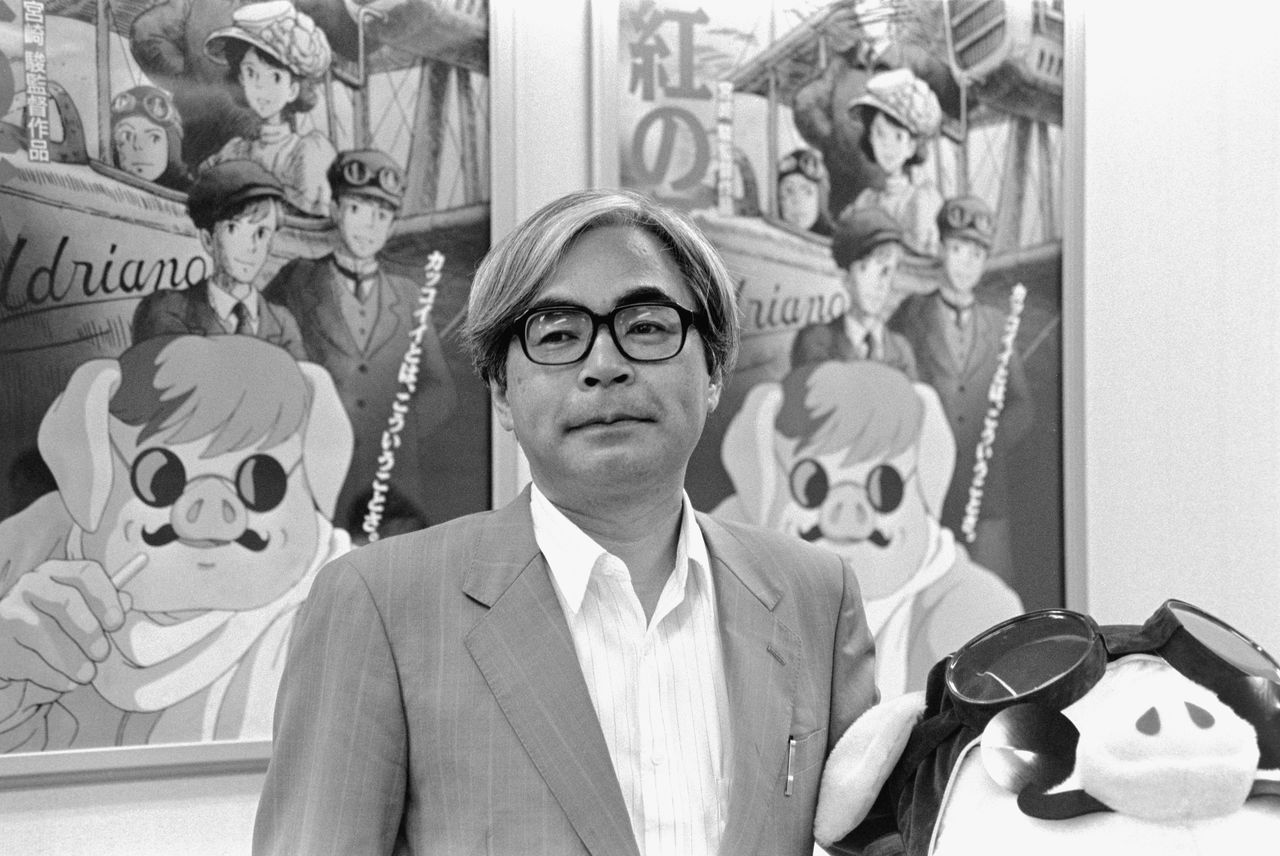

Miyazaki Hayao in 1992, around the time of the release of Porco Rosso. (© Jiji)

Howl and Sophie fly through the air in a scene from Howl’s Moving Castle (2004). (© Studio Ghibli)

The Boy and the Heron never explains how the alternate reality inside the tower is sustained, or even what the titular heron ultimately represents. These are logical gaps—yet the distinctive quality of Miyazaki Hayao’s stories can be found within them.

Many viewers expect resolutions in movie stories, where the events that occur are explained, and things foreshadowed are resolved. Miyazaki leaves the interpretation of these storytelling gaps up to the audience, prompting them to think. His fans do not expect the usual conventions; they come to luxuriate in the director’s imaginary worlds.

Going Global

Miyazaki rose to prominence in Japan as the creator of the 1984 movie Nausicaä of the Valley of Wind. However, while My Neighbor Totoro (1988) and Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989) won some popularity overseas through videotape sales, this did not translate into wide recognition for Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli.

Nausicaä with a giant insect in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). (© Studio Ghibli)

Totoro takes Satsuki and Mei on a trip through the air in My Neighbor Totoro (1988). (© Studio Ghibli)

Ashitaka and San riding on wolfback in Princess Mononoke (1997). (© Studio Ghibli)

Miyazaki’s overseas reputation as a film director rose with the North American release of Princess Mononoke, his most enigmatic film to date, in 1999. But the most decisive moment came with the Berlin International Film Festival’s crowning of Spirited Away with the Golden Bear award in 2002—the first time an animated film had been so honored. Perhaps Miyazaki’s films’ depth, accommodating many differing interpretations, led to the global acclaim.

Chihiro and No-Face in Spirited Away (2001). (© Studio Ghibli)

Miyazaki Hayao (center) among Studio Ghibli representatives at a press conference in Tokyo in February 2002 after Spirited Away received the Golden Bear award. (© Jiji)

The interest in the potential of animation as a storytelling medium continues to grow in the movie world. At this year’s Cannes Film Festival, animated works were screened in the official competition, Un Certain Regard, and Director’s Fortnight selections. These were not films intended for children, but rather works thought to have a certain weight and presence as films themselves. It could be said that Spirited Away blazed a trail for animation at major festivals. Miyazaki’s and Ghibli’s winning of the Palme d’Or should be considered against this backdrop.

A Belief in the Future

Miyazaki often takes pains to explain that he makes films for children. This stance is reflected in a representation of hope for the future in his films. Nausicaa, protagonist of Nausicaä of the Valley of Wind, never gives up even as the world dies around her. In The Boy and the Heron, Mahito accepts his new family.

The real world is filled with dark news and happenings. Miyazaki tells children the importance of staying positive and believing in a bright future, no matter how malicious the world may seem. Of course, children are far from the only ones drawn to a hopeful future. So are their parents and grandparents. The complexity of Miyazaki’s worlds is what resonates across the generations.

Complex worldviews, uncompromising craftsmanship, and ultimately hopeful outlooks draw children and adults alike to Miyazaki’s films. I believe that they not only represent what the world wishes to see in Japanese animation but also push the envelope of theatrical storytelling as a whole.

(Originally published in Japanese on May 24, 2024. Banner image: A picture of Miyazaki Hayao in 2016 [© Nippon.com], alongside film posters for Spirited Away and The Boy and the Heron [© Studio Ghibli].)