The Cats of Gokōgū Shrine: Sōda Kazuhiro’s Exploration of a Community of Locals and Strays

Cinema- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Documentary filmmaker Sōda Kazuhiro adheres to what he calls the “10 Commandments” of his observational approach. The precepts—including injunctions against pre-shooting research, the use of narration, and reliance on scripts—have produced works earning him acclaim in Japan and overseas, starting with his first documentary in 2007, the Peabody Award winning Campaign. In his tenth observational film, The Cats of Gokōgū Shrine, Sōda, a graduate of the prestigious School of Visual Arts in New York, focuses his lens on the residents—human and feline—of Ushimado, a quaint coastal town on the Seto Inland Sea in Okayama Prefecture.

The work is Sōda’s first since leaving New York, his base for 27 years, and resettling in Japan. It received a warm reception at the seventy-fourth Berlin International Film Festival, where it made its debut.

Ushimado’s port and the Seto Inland Sea beyond. (© 2024 Laboratory X, Inc)

Life with Cats

Sōda has an intimate connection with Ushimado. It has been the focus of two previous documentaries, Oyster Factory (2015) and Inland Sea (2018), and is where he and his wife and producer Kashiwagi Kiyoko, whose mother grew up in the town, now call home. In The Cats of Gokōgū Shrine, he turns his attention to a cluster of strays that roam in and around the small Shintō shrine near the harbor, through which he movingly reveals the inward struggles of the community itself.

The cats are a tourist draw, elating sightseers with their antics. Although feral, they are well fed by visitors as well as residents, including local fishermen and anglers who toss them tidbits from their lines. At the same time, the community is struggling to come to terms with the sanitary and other concerns related to its feline inhabitants. A controversial trap-neuter-return program attempts to keep their number in check, as manifested by the V-shaped nicks on ears of many cats. In fact, it was this scheme more than the strays themselves that piqued Sōda’s curiosity and serves as the basis of the film.

A cat lounges within the confines of the Gokōgū Shrine. (© 2024 Laboratory X, Inc)

A life-long cat lover, Sōda says that he did not initially have a documentary in mind—he insists that he never begins from a premise, but prefers for the theme to come into focus naturally through the filming process. Living in Ushimado, he found himself drawn in by the town’s relationship with its population of strays. His wife had volunteered with the TNR program, and when he heard that a trapping event was scheduled, he picked up his camera and headed to the shrine to film, declaring that “I simply kept the camera trained on what was going on around me.”

Local children play with one of the town’s tamer street cats. (© 2024 Laboratory X, Inc)

The TNR program piqued his interest as it seemed a shift away from integration of the feline population to one of removal, a trend that gave him pause. “I want to live in a society that makes room for cats,” he exclaims. “One that is gracious and not self-absorbed, and where there’s an acceptance of others who might not fit so snugly into the mainstream. Are we heading in a direction that will make us happy? I wonder about that.”

Delicate Balance

The strays have their ardent fans as well as detractors, who see them as a nuisance. To avoid stirring up conflict, Sōda says that the cat-friendly circle has to be careful not to draw too much attention when feeding the animals. Putting his personal views on the ethics of TNR aside, he recognizes the program as offering a compromise between the two camps. “On the one hand, it helps keep the feline population under control,” he explains. “This presents something of a conundrum, though, because if all the animals are fixed, the colony will eventually dwindle away entirely. And then where will we be?”

Strays trapped as part of the town’s TNR program stare out of cages. (© 2024 Laboratory X, Inc)

Filming the comings and goings of the pastoral community, Sōda slowly reveals the underlying tension surrounding the cats, which in turn unmasks broader concerns bearing down on the town. “The cat question runs like a rift through the middle of the community,” Sōda explains. “It was taboo to even bring it up openly, which forced me to be especially cautious when filming.”

The cats are popular with the children of Ushimado, but many adults say there are too many of the animals. (© 2024 Laboratory X, Inc)

Tensions inevitably bubble to the surface, but Sōda does not shy away, using his trademark long takes to observe and glean insights. “I knew making the documentary would stir emotions and exacerbate the issue around the cats,” he says. “But it was a story worth exploring. I didn’t have an agenda. I only shot what was going on around me, and from that the inner workings of the community gradually came into view.”

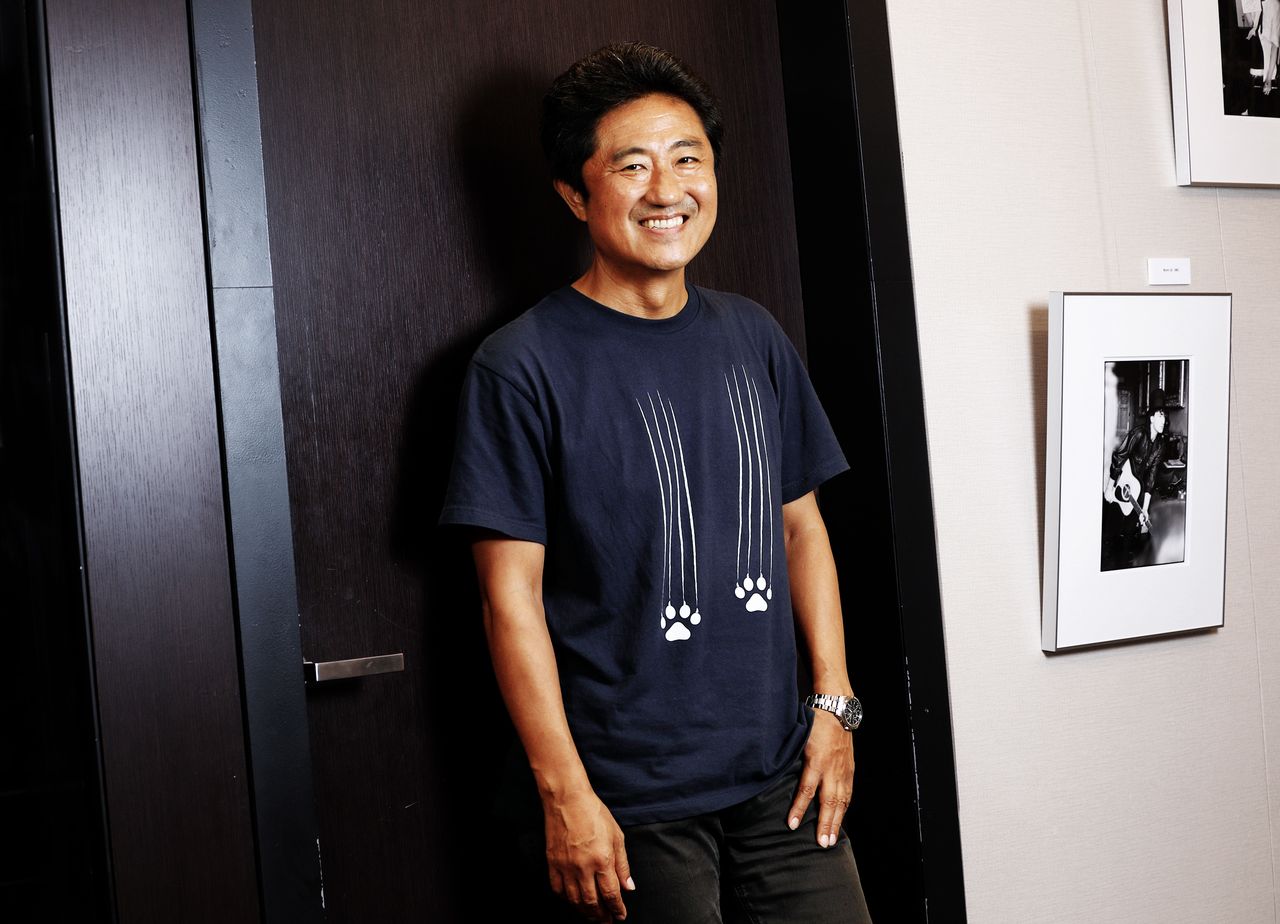

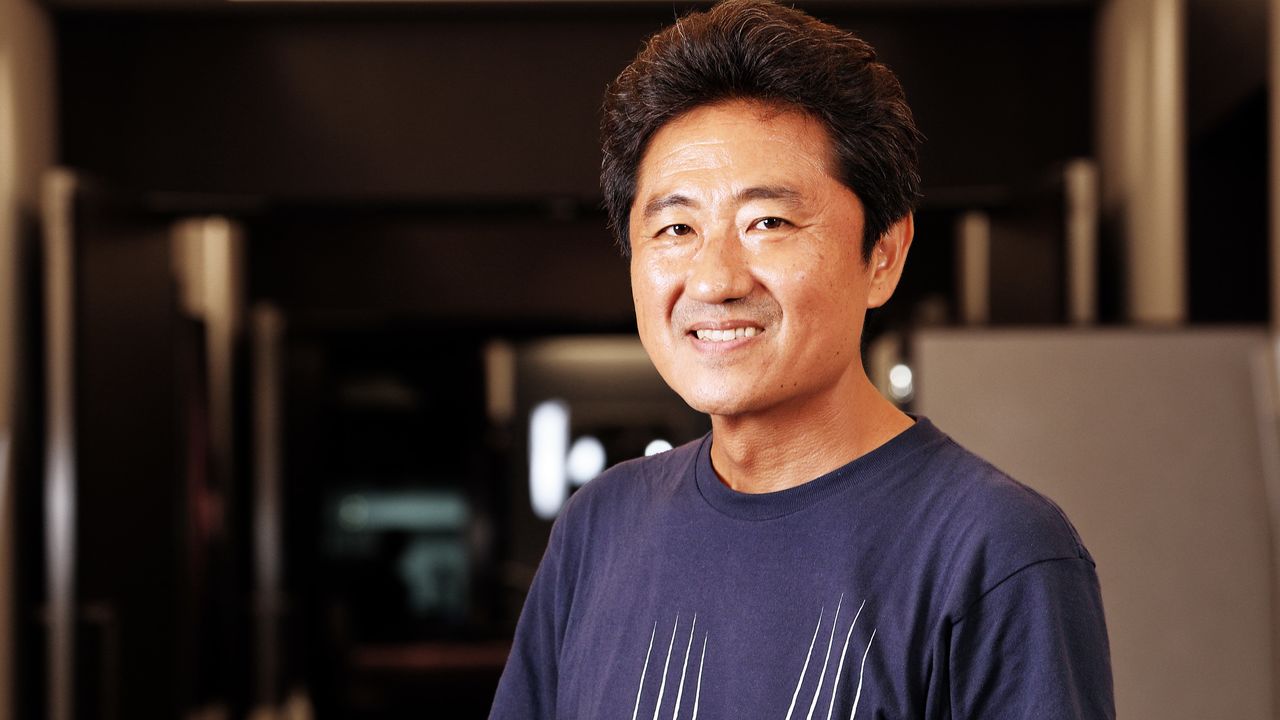

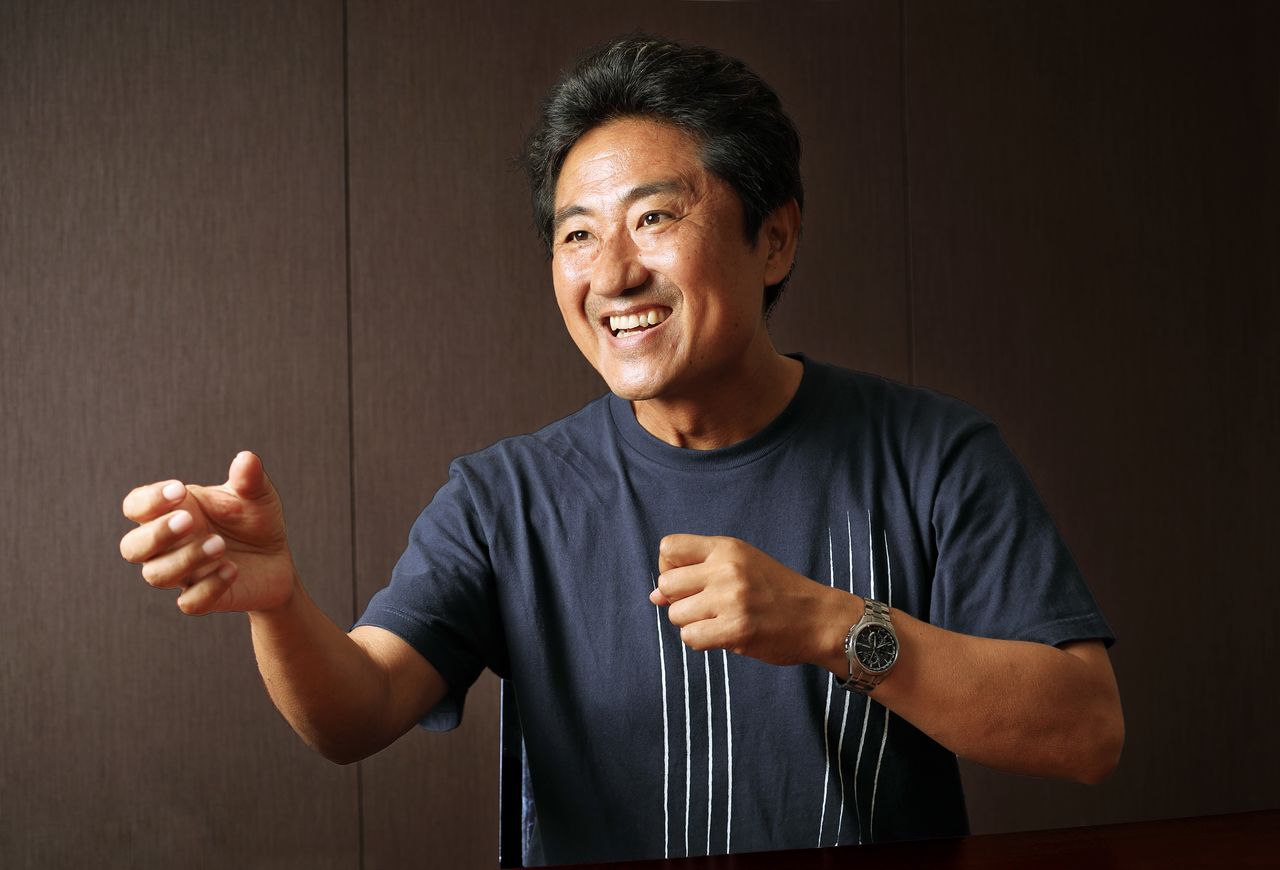

Sōda Kazuhiro. (© Hanai Tomoko)

Shrine Intersections

The feral cats are a fraught issue, but the community follows a nonconfrontational approach to resolve the conflict. “Disagreements rarely boil over in Ushimado,” describes Sōda. “Even when at loggerheads, people don’t typically try to beat down the other person but rather acknowledge the other side’s point of view. There’s an understanding among residents that accepting differences is the glue that keeps society together.” The approach stands in stark contrast to the widening polarization he sees in society and growing tendency to view alternative opinions as wrong.

Ushimado residents meet at an old house that now serves as a community center. (© 2024 Laboratory X, Inc)

From the outset of the film, Sōda focuses his attention on the Gokōgū Shrine as the heart of the community. Stationing himself there for several days to capture TNR activities, he says that he became aware of the vast array of visitors. “Shrines are unique and fascinating public spaces. People come and go freely, visiting for all sorts of reasons. They serve as spiritual anchors for residents, but they also draw outsiders. Maybe that’s why the cats feel so at home there. In a sense, they’re a crossroads linking the interior and exterior worlds. So many different things came into perspective as I sat there observing the surroundings.”

A sign serves as a convenient covering from the rain. (© 2024 Laboratory X, Inc)

Sōda says that each new observation brings fresh insights. As the social issues confronting Ushimado and similar towns come to light, they ripple across the scenery like a stone thrown in a still pond. Sōda does not avert his lens from the uncomfortable, keeping it trained on his subjects in search of discoveries that will challenge his preconceived conceptions. “The desire to be amazed is inherent to the act of observing,” he says. “There is nothing thematic about it.”

As a creator, though, Sōda, is fully aware that his subjective decisions play a role in shaping the thematic tone of his films. He admits that social norms can make life difficult or lead to conflicts, and that unconsciously, he is searching for ways to overturn those norms. “Personally, I’ve long been troubled by our consumer society’s constant demand for things to be faster and stronger, and there to be more and more stuff. I find it a challenge to live within that framework.”

A cat enjoys a moment of post-feeding bliss. (© 2024 Laboratory X, Inc)

The Art of Observation

The editing process for Sōda is a chance to think deeply about the footage, from which arise new insights into a film. “I make certain to set down to the task with an open mind, otherwise I will choose scenes that fit my bias, preventing me from discovering what lies beneath the surface.”

To start out, Sōda pieces together some 70 or 80 scenes into an initial cut. “These are never very interesting,” he chuckles. “It’s a struggle to keep from nodding off. It’s so dull, it’s almost embarrassing to watch.” Only when he begins clipping, adding, and rearranging the order of scenes does the film take shape. “It’s a taxing process, but it brings to light what was previously unseen. Then, there comes the moment when the overarching theme suddenly comes into focus.”

Recreational anglers are irresistible to the town’s strays. (© 2024 Laboratory X, Inc)

Experiencing these instances of revelation are Sōda’s greatest reward and what keeps him making his observational films. Some may wonder if he can actually step into filming without a plan and with an open mind, to which Sōda has this to say:

“It’s certainly a challenge. Relying on previous successful formulas and patterns would be easier, but following a blueprint would keep me from uncovering the truth. That’s why it’s essential to observe. My films are about discovery. Through watching and listening, it’s possible to see the world as it is.”

Trailer (Japanese)

(Originally published in Japanese. Interview and text by Matsumoto Takuya. Interview photos © Hanai Tomoko.)