“Look Back”: Anime Adaptation Captures the Joy and Agony of Artistic Creativity

Cinema Anime Manga- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The World of Manga Artist Fujimoto Tatsuki

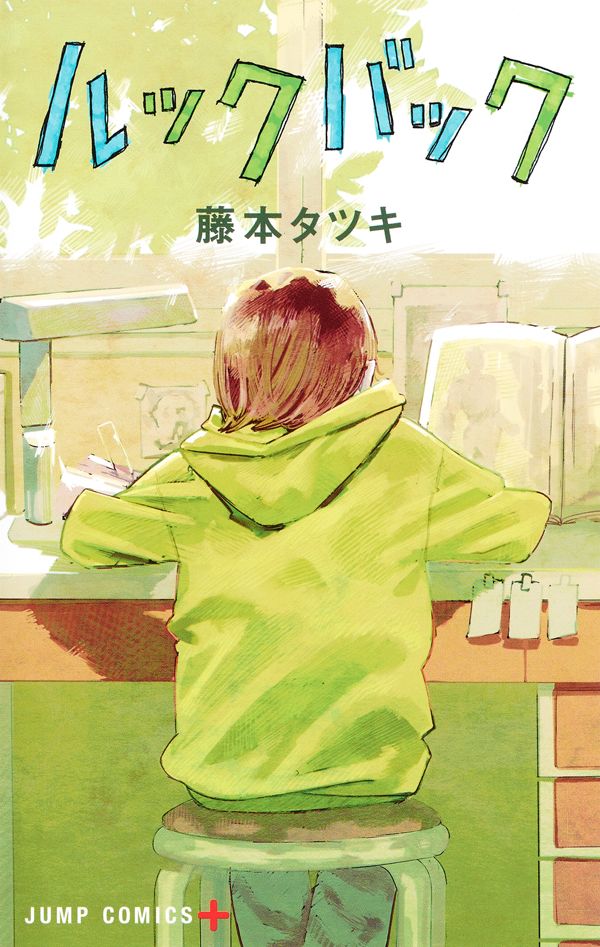

Fujimoto Tatsuki is best known for his smash-hit manga series Chainsaw Man, with 26 million copies in print globally. Its “Public Safety Saga” arc drew to a close in 2020. But before launching into the next arc in the series, Fujimoto made a surprise announcement: he would release a standalone story called Look Back first. The move sparked great anticipation among both fans and industry insiders: what kind of story might the megahit manga creator unleash on the world?

Look Back centered on a pair of young women trying to become manga artists. Fujino is an elementary schoolgirl who wins acclaim from her classmates for a four-panel manga published in the school newspaper. Full of pride, she downplays her hard work by claiming that it only took her five minutes to draw. The other protagonist is Kyōmoto, a classmate who refuses to leave her house and go to school. When Kyōmoto happens to see Fujino’s comic in the paper, she is consumed by jealousy over Fujino’s skills.

Fujino and Kyōmoto eventually meet, become kindred spirits, and decide to work on a manga together. The pair share a dream of becoming professional manga artists, but encounter some hard, unexpected realities along the way.

This fresh coming-of-age story between two young girls takes some gripping turns. (© Fujimoto Tatsuki/Shūeisha; © 2024 Look Back Production Committee)

It is clear that this story is a deeply personal one for Fujimoto. The two protagonists, Fujino and Kyōmoto, each share a kanji-character with Fujimoto. His alma mater the Tōhoku University of Art and Design makes an appearance, and Fujino’s manga Shark Kick feels like a twist on Fujimoto’s own debut, Fire Punch.

In promoting the animated adaption of Look Back, Fujimoto said that the work represented him forcing himself “to come to terms with something he previously couldn’t.” The film’s director, Oshiyama Kiyotaka, says that he felt himself “resonating” with Fujimoto as he read the manga.

The Solitude, Pain and Pleasure of Creation

Director Oshiyama cut his teeth as an animator on projects including Evangelion: 2.0 You Can (Not) Advance (2009), The Secret World of Arrietty (2010), and The Wind Rises (2013). For Look Back, he did triple-duty as a character designer, animation director, and animator. He drew much of the movie himself, using Fujimoto’s distinctive linework to bring the passion of creatives to the screen.

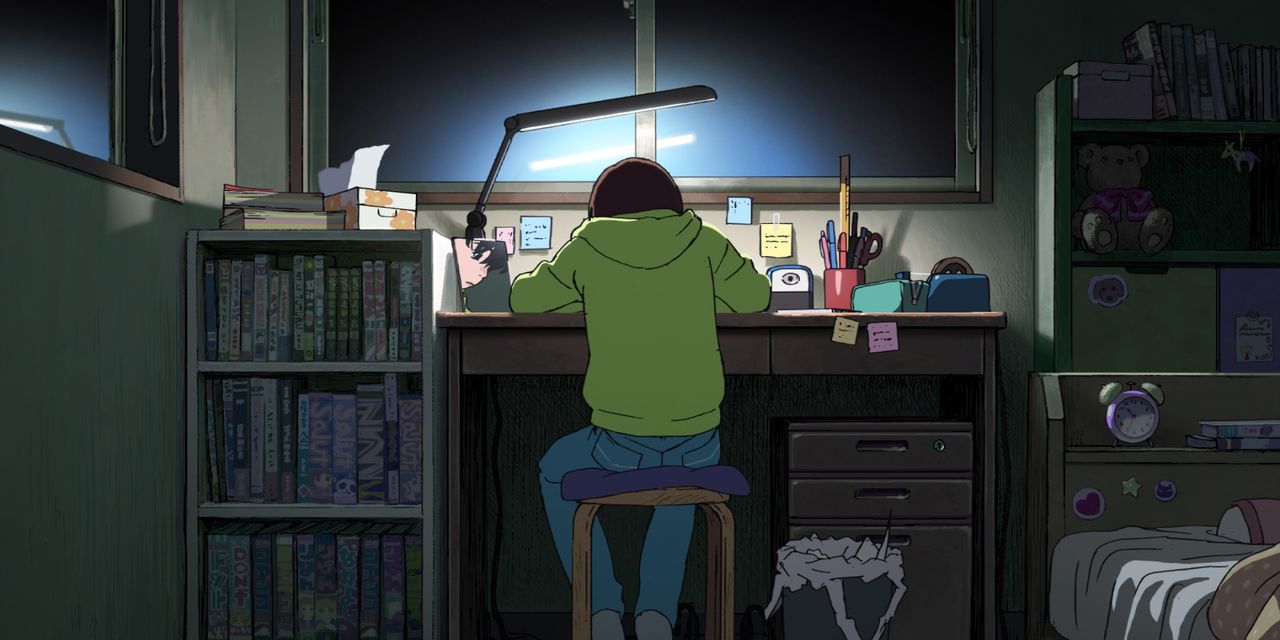

As the movie begins, the camera pans from a moon partly obscured by clouds to the light emerging from houses, then focuses in on a single dark room, in which a young girl works with pencil in hand by the light of a desk lamp. She works, pauses to think, and continues to draw. A mirror on the desk captures the expression on her face, revealing her true feelings.

This opening sequence is not in Fujimoto’s manga. But the scene of a solo creative locked in “battle” with the page on her desk in quiet solitude quickly sets the tone for the movie. This struggle is what stirs Fujino’s heart when she encounters Kyōmoto, and the reason for her joy when Kyōmoto appreciates her work. And it is something that she cannot escape as she continues to draw.

The film lays bare the “battles” that those who want to make animation face. (© Fujimoto Tatsuki /Shūeisha; © 2024 Look Back Production Committee)

The film is a faithful adaptation of the comic, highlighting the struggles, the joys, and the loneliness of those who create. (The differences with the comic can be found in subtle changes to the story’s structure and dialogue.) Kawai Yuumi, who voices Fujino, and Yoshida Mizuki, who voices Kyōmoto, do such an excellent job drawing out the delicate emotions of these still-immature young creators that it’s hard to believe this represents their debuts as professional voice actors.

Animation’s Ability to Stitch Together Time

Countless comics have been adapted into live-action or animated features. What makes Look Back unique is its approach to depicting the flow of time. This aspect, impossible to portray on paper, sets it apart from the manga, bringing new depth to the story.

Particularly key is the time Fujino spends at her desk drawing manga, the time she spends walking along the road dejected over Kyōmoto’s talent, the time when Kyōmoto runs out of the house in surprise when Fujino unexpectedly shows up, and the time when Kyōmoto dances through the rain as she basks in the pleasure of having her talent recognized.

All of these moments play out in still frames on the manga page. But the power of animation is the ability fill in the gaps between, letting the scenes take on new life, touching the hearts of viewers in ways that are thrilling and satisfying.

The score by Haruka Nakamura is used to great dramatic effect. (© Fujimoto Tatsuki/Shūeisha; © 2024 Look Back Production Committee)

The charm of live-action films is their ability to capture surprising moments by chance. Animation, being made by hand, frame by frame, lacks this spontaneity. There might be happy accidents in the process of drawing, but the characters and their expressions, the scenes and backgrounds, and the flow of time linking everything together are the product of meticulous work, driven by vision and passion.

The film represents a fusion of the creative visions of Fujimoto, who dreamed up the story, and Oshiyama, who imbued it with a sense of time through his direction. It is no coincidence that the collaboration resembles Fujino and Kyōmoto’s in the drama. The story of those two characters, with their incessant creative drives and conflicts, symbolizes the struggles faced by all who dedicate their lives to drawing, whether on the page, the screen, or anywhere.

The Terrifying Energies of Creation

Creation and creativity are not always positive forces. The brilliance of Look Back can be found in its depiction of the raw forces unleashed in the act of creating something, as told through the stories of two talented girls. The worlds, the products, they create may have no practical use in and of themselves, but possess the power to change other peoples’ lives. This energy can drag some into a terrifying abyss.

From the release of the original manga, much discussion has centered on aspects of the story resembling the real-life arson attack on Kyoto Animation in July 2019. When Fujimoto said that the work represented him forcing himself “to come to terms with something he previously couldn’t,” it suggests that the story was more than a personal exploration: it was an attempt to reconcile the relationship between creation and society. Perhaps this is why the second half of the film feels so compelling. Fujimoto’s inability to come to terms with tragedy as he began the manga gives the drama even more poignancy.

This is not simply because this film is the product of many hands. As I wrote, it handles the flow of time with a deftness that manga cannot. The time of Fujino and Kyōmoto is rendered in exquisite detail. The preciousness of that time is powerful stuff, but so too is the feeling that time once passed can never return. The emotional impact of the climax is something only a film, with its flow of time, can provide.

The strength and limitation of manga is the medium’s ability to parse time into discrete moments, into frames and pages. This is carried through the film, from its opening moments until its inevitable end. Even at less than an hour in length, the film’s sense of time is exquisite: a new masterpiece born out of the work of one of today’s leading manga artists.

(© Fujimoto Tatsuki/Shūeisha; © 2024 Look Back Production Committee)

Trailer (Japanese)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner image © Fujimoto Tatsuki/Shūeisha; © 2024 Look Back Production Committee.)