Ōkuma Shigenobu: The “Fourth Man” of Japan’s Modernization

Books History Politics Education- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A “Dragon” of Japanese Politics

Most people in Japan know Ōkuma Shigenobu (1838–1922) as the founder of Waseda University in Tokyo, one of the country’s most prestigious private institutions of higher education. Ironically, fewer people today are familiar with his achievements as a statesman or realize just what an important figure he was in the politics of his time. This new book aims to put that right.

Having graduated from the economics department at the University of Tokyo, Suzuki admits that he has no personal connection with Waseda. “My interest was in Ōkuma the politician,” he writes. “I wanted to discuss the important contributions he made, as one of the most important political figures of his time, by extracting Japan from a prolonged crisis during the first two decades of the twentieth century.”

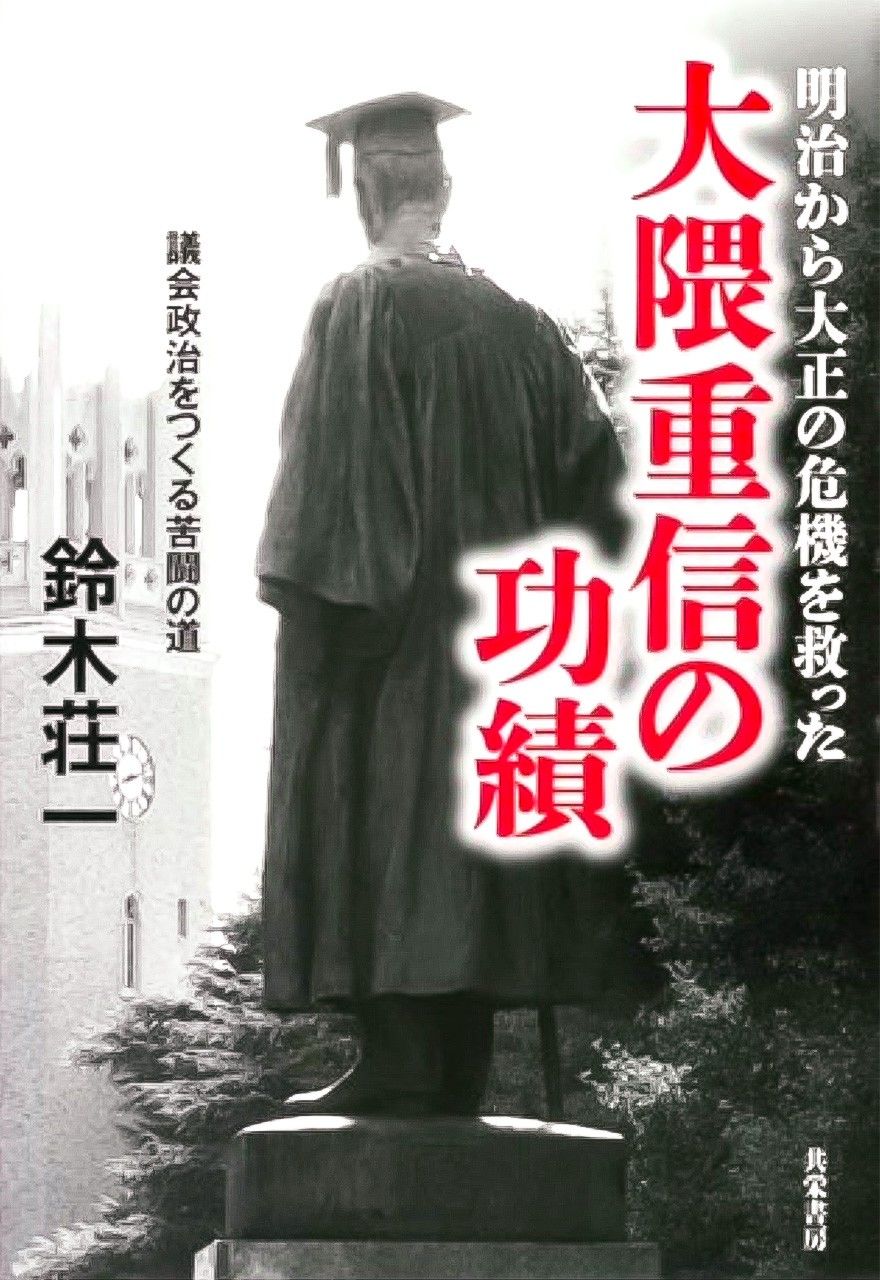

A statue of Ōkuma Shigenobu at Waseda in Tokyo on “Homecoming Day” on October 22, 2023. (© Izumi Nobumichi)

The conventional view of Japanese history recognizes three Great Nobles of the Restoration: Saigō Takamori, Ōkubo Toshimichi, Kido Takayoshi. Suzuki regards Ōkuma as the “fourth man” of the Meiji Restoration, and credits him with “cleaning up the mess and rescuing the country from a national crisis.” He compares him to the “relief pitcher” in baseball, who is brought on when the strength of the starting pitcher begins to wane.

Until he stepped up to the plate in this emergency capacity, Ōkuma had remained far from the public eye, like a deep-sea fish skulking on the seabed, building up his strength and immersing himself in study and reflection. The world at large had no idea what he was up to, until Japanese diplomacy stumbled into a blind alley and crisis threatened—when he emerged suddenly onto the stage to cut the Gordian knot and solve the problems that had been troubling the country. Then, once order had been restored, he stepped quietly back into the shadows, lamented by his public.

Suzuki’s descriptions of Ōkuma’s early years reminded me of the life cycle of a dragon as described in the I Ching, the ancient Chinese book of divination: beginning as a Hidden Dragon lurking beneath the earth, then passing through various stages of growth and development before maturing into a magnificent Flying Dragon that takes to the skies and soars majestically before eventually declining once more.

Ōkuma was thrust from his government position in 1881 following a political crisis sparked by disagreements about the form the country’s constitution should take. (Ōkuma advocated a liberal constitution on the British model but was opposed by Itō Hirobumi and others who favored a Prussian-style constitution with more power for the emperor.) But this setback proved temporary, and he later returned to power, serving as foreign minister and (twice) as prime minister. This book brings his turbulent, vicissitudinous life into clear relief, as Ōkuma’s life is skillfully interwoven with the wider history of modern Japan.

A Dazzling Debut

Ōkuma burst onto the diplomatic scene in 1868, shortly after the Meiji reformers took power. Despite its reformist character, the new government maintained the old regime’s ban on Christianity. From the 1850s, populations of “hidden Christians” began to emerge from seclusion in Nagasaki and other parts of Kyūshū as Christians returned to Japan and churches were built for the first time in centuries to cater for the foreign population. The new government cracked down on these Japanese Christians, and there were several widely publicized incidents of repression and torture. The imposing British diplomat Harry Parkes was delegated to submit a strongly worded rebuke to the new government on behalf of the Western powers. Since Parkes had provided influential backing for the new government in its struggle against the old regime, the Meiji oligarchs found themselves in a difficult position. According to Suzuki’s book, “Ōkuma, totally unknown at the time, was selected to represent the new government, and utterly defeated his British opponent in a debate on tolerance for Christianity, saving the new government from a difficult predicament and rising instantly to prominence.”

Ōkuma was born into a samurai family in the Saga domain in Kyushu. In his twenties, he traveled to study in Nagasaki, where he learned English from a Dutch-American missionary named Guido Verbeck. It was thanks to what he learned in Nagasaki, Suzuki says, that Ōkuma was able to stand up to Parkes and even outargue him: “Because he had studied the New Testament and the American Declaration of Independence with Verbeck, he knew that the history of Christianity was a history of war, invasion, and repression. This counterattack was possible thanks to Ōkuma’s learning and debating skills.”

Developing Close Ties With Britain and the United States

It was after he lost his place in government in the upheavals of 1881 that Ōkuma founded the Tokyo Senmon Gakkō, which developed into Waseda University. His political career revived when Itō Hirobumi recalled him to government as foreign minister, tasked with revising the notorious “unequal treaties” with the Western powers. Negotiations had to be temporarily halted after he lost his right leg when a member of an ultranationalist group threw a bomb into his horse-drawn carriage. In 1898, he headed Japan’s first ever party-led cabinet, holding the offices of prime minister and foreign minister concurrently.

In 1914, at the age of 76, Ōkuma became prime minister for the second time. Suzuki has high praise for this second period in office, describing the second Ōkuma government as “the outstanding cabinet of the Taishō era [1912–26), which succeeded in resolving the thorny problems Japan had faced since the Russo-Japanese War, notably the challenge of restructuring the public finances.”

It was during Ōkuma’s second period as prime minister that he brought Japan into the Great War on the Allied side, on the basis of Japan’s treaty with Britain. Japan emerged on the winning side, taking control of German possessions in China and the Pacific in the process. Suzuki claims that under War Plan Orange, the United States had a plan at the time that envisioned a military conquest of Japan to secure American dominance in the Pacific.

Suzuki writes that “the second Ōkuma cabinet joined World War I in support of its British ally, therefore fighting on the same side as the United States against Germany and rendering Plan Orange moot.” Together with his pro-British foreign minister, Katō Takaaki, Ōkuma pursued a foreign policy based on concord and collaboration with Britain and the United States, and his policy was to “avoid any increase in military spending by working to alleviate threats to national security.”

However, the Ōkuma government was toppled by political rival Yamagata Aritomo, one of the Chōshū faction of genrō elders and an implacable opponent of Britain. The historical reality, Suzuki writes, was that with this, “the Anglo-Japanese Alliance was abandoned, and Japan became ensnared in a position of international isolation that eventually led to the disaster of the Pacific War.”

The Hero from Saga

The author describes depicts the character of his Saga-born hero in the following terms:

He had no lust for money, power, or worldly success. But his problem-solving abilities, his talent for making friends, and his desire for self-expression went far beyond the ordinary. In that sense, his was an easygoing, uncomplicated character somewhat atypical of the Japanese men of his time.

He also had an unusually wide range of acquaintances from across political and intellectual life. In his younger years, the Ōkuma residence in Tsukiji hosted gatherings of figures like Itō Hirobumi and Inoue Kaoru from Chōshū, men who had served the shogunal government like Shibusawa Eiichi, and young cabinet ministers like Maejima Hisoka. “These figures from different backgrounds would gather at the Ōkuma residence in Tsukiji for days on end, debating foreign policy, international affairs, and public finances through the night. Ōkuma’s house became known as the “Mount Liang of Tsukiji,” after the mountain that provides refuge to the 108 heroic “outlaws of the marsh” in the classic Chinese novel Shui hu juan (The Water Margin).

A statue of Ōkuma at a memorial museum in his birthplace of Saga, Saga Prefecture. Photo taken on September 22, 2023. (© Izumi Nobumichi)

Ōkuma was a man of impressive stature for his time (apparently 1.8 meters tall). On November 22, 1908, he walked with his false leg onto the Totsuka Baseball Ground at Waseda, where he threw the first pitch in a friendly game between a selection of professionals from the US leagues and a Waseda University team—remembered today as the first ever international game between teams from Japan and the United States. Unfortunately, the pitch was wild, and veered far outside the strike zone.

Feeling it would be disrespectful to allow the university president’s ceremonial pitch to be called as a ball, the Waseda captain deliberately took a wild swipe to ensure a strike. Since then, it has become a tradition that the batter facing the first ceremonial pitch always swings and misses. It is perhaps indicative of the breadth of Ōkuma’s talents and influence that this biography covers everything from diplomatic grand strategy to etiquette on the baseball field.

Meiji kara taishō no kiki o sukutta Ōkuma Shigenobu no kōseki: Gikai seiji o tsukuru kutō no michi (How Ōkuma Shigenobu Saved Japan from Crisis in the Early Twentieth Century: The Struggle to Create Party Politics)

By Suzuki Sōichi

Published by Kyōei Shobō

ISBN: 978-4-7634-1113-6

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo courtesy Kyōei Shobō.)