Endō Shūsaku: New Study Explores the Final Masterpiece by Japan’s Celebrated Christian Author

Books Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The Culmination of a Literary Life

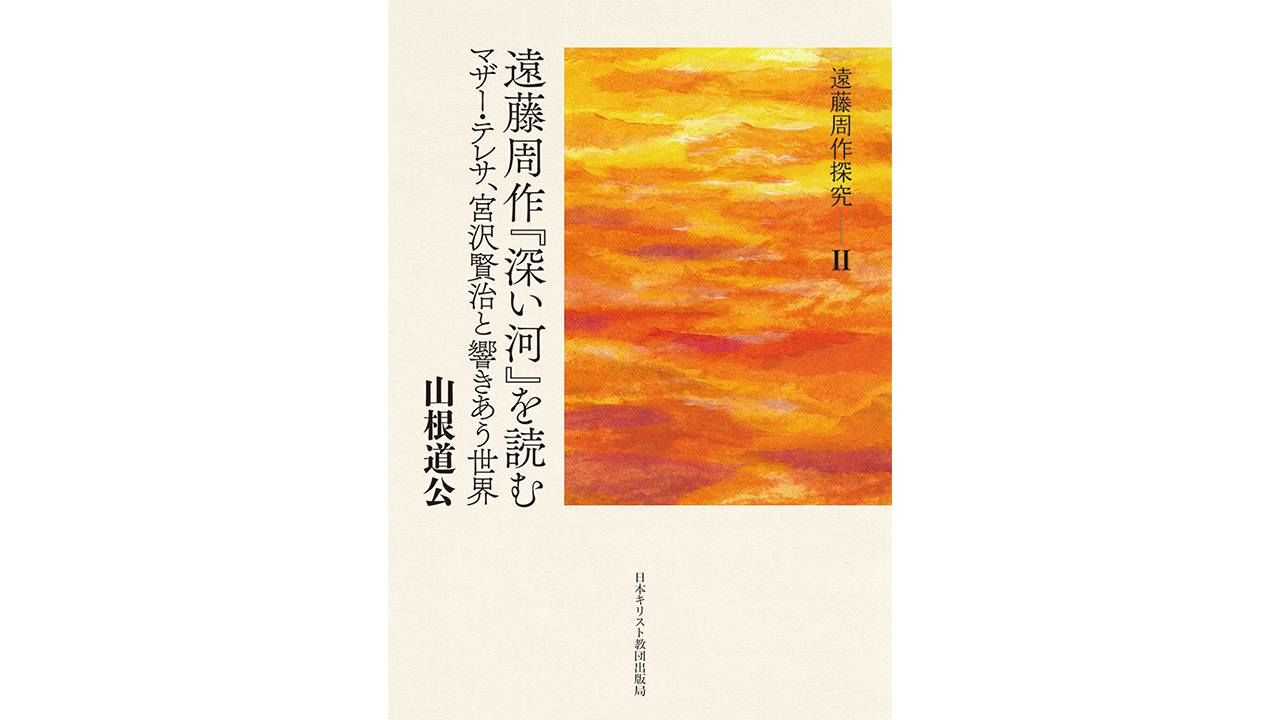

The author of a new study on Endō Shūsaku, Yamane Michihiro is Japan’s leading specialist on the works of the author, whom he knew personally. An earlier version of Endō Shūsaku, Fukai kawa o yomu: Mazā Teresa, Miyazawa Kenji to hibikiau sekai (Reading Endō Shūsaku’s Deep River: Mother Teresa, Miyazawa Kenji, and Worlds in Sympathy) appeared in 2010, and this revised edition incorporating additional material has now been issued as the second part of a three-volume series of studies to mark Endō’s centenary.

Fukai kawa (trans. by Van C. Gessel as Deep River) was Endō’s last major work of fiction, appearing in June 1993. Professor Yamane describes the novel as the “recapitulation and summing up of Endō’s life and work.” Given the importance of the novel in the author’s oeuvre, Yamane immediately felt he wanted to explore the topics addressed by the book and its characters as closely as possible. The result was a series of essays that ran for two years in a quarterly magazine from September that year under the title “Reading Deep River.” Incorporating close readings and drawing on an impressive range of scholarly sources, Yamane’s scholarship shed new light on Endō’s final message to his readers. This groundbreaking study makes up the bulk of the new book.

The Real-Life Priest and Friend Who Inspired a Literary Hero

As the culmination of Endō’s work as a writer, the novel introduces a gallery of characters variously evocative of people from the author’s previous novels, as well as Endō himself, his parents, and close friends. “The novel has quite a dense structure. It’s as if different aspects of the rich tapestry of Endō’s life up to that point are projected onto the various characters in the novel,” Yamane says.

The plot incorporates several different elements, among them the bonds between a married couple, the interconnectedness of the human and animal worlds, and the lingering influence of an old mentor and friend. As the novel develops, it reflects the changing patterns of characters’ lives: their troubles and secrets, and the complex relations that bind them all together.

The novel brings these diverse characters together as a Japanese tour group to India. Each of the participants has his or her own reasons for joining. The story follows the travelers as they make their way to the sacred city of Varanasi (Benares) on the banks of the Ganges, the holiest site in Hinduism.

One of the novel’s protagonists is Ōtsu, a devout Christian. After graduating from the philosophy department of a Catholic university in Tokyo, Ōtsu trains for the priesthood at a monastery in France, but gradually comes to feel uncomfortable with aspects of European Christianity. Regarded as a heretic by his fellow seminarians for his unconventional views, he wrestles with a longing to develop an approach to Christianity that suits the Japanese mind. He winds up in Varanasi, where providence brings him together with the Japanese tour group.

Another character who plays an important role in the story is Naruse Mitsuko, who as a non-believing female student once seduced Ōtsu during their days as students in the French literature department, partly as a joke, and almost persuaded him to renounce his faith. She soon ends their relationship, but later visits him in France during his time as a theology student, and continues to correspond with him after her arranged marriage ends in divorce. Mitsuko continues to search for “true love,” and is driven to join the tour largely because she knows that Ōtsu is living in India.

Yamane’s book reveals the real-life model for the Ōtsu character: Father Inoue Yōji (1927–2014). Inoue and Endō traveled together as students bound for France, fourth-class passengers on La Marseillaise out of Yokohama. Ultimately, both men struggled to adjust to the assumptions of European theology. Inoue spent his life trying to reconcile Japanese culture and Christianity, and Endō, whose own work often examined the Christian faith from a Japanese perspective, referred to Inoue as his “old comrade in arms.”

Tolerance and Respect

Hindus believe that bathing in the sacred Ganges can cleanse a person from sin. It is said that if a person’s ashes are scattered on the river after cremation, that person will achieve moksha and be liberated from the cycle of rebirth. The book describes Ōtsu’s life in the Hindu holy city as “an expression of compassion and love that boldly transcends the framework of conventional Christianity.”

Convinced that Christ lives even within the anonymous Hindu faithful who die penniless and unremarked in Benares, Ōtsu cares for the dying with warm respect for their faith, and after death commends their souls to Jesus before having their bodies cremated on the burning ghats of the Holy Ganges.

Although they never met, Endō exchanged letters with Mother Teresa (1910–1997) in Calcutta. In Deep River, Ōtsu is an admirer of Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948), father of Indian independence, and the novel quotes from Gandhi’s writings on religion. The nuns who care for the poor at Mother Teresa’s hospice also appear in the novel.

In his study, Yamane points to the similarities between the lives of the Hindu Gandhi and the Catholic Mother Teresa. “Both provided a vivid example of lives dedicated to their respective faiths, while showing respect and tolerance for other religions.” Part of the message of Endō’s last novel is a plea for tolerance and understanding among the diverse religions of the world.

Yamane also suggests parallels between Deep River and the spiritual outlook of Ginga tetsudō no yoru (trans. by Julianne Neville as Night on the Galactic Railroad) by Miyazawa Kenji (1896–1933). Kenji was a believer in the Lotus Sutra, but also studied the Bible. Endō likewise became increasingly interested in Buddhism in his later years. Yamane notes that an open and foundational religious sensibility that allows different religions to coexist in place was a key theme in the works of both authors.

A Minority Writer Who Found Mainstream Popularity

“Since the dawn of the twenty-first century,” Yamane writes, “the world has been caught in a worsening spiral of violence, terrorism, and retaliation, driven by a clash of civilizations that is exacerbated if not caused by religious differences.”

Yamane believes that in writing Deep River, Endō drew on his last reserves of energy and creativity to complete a final message for our age—and one that contains precious hints on how to overcome religious tensions and violence.

It is now 30 years since Deep River was published, but sectarian conflict continues to tear apart the international community. The issues addressed in Endō’s last novel remain vitally important today, more than a generation after he died.

Endō’s best-known work, Chinmoku (Silence) (center) is contained in Volume 6 of the author’s complete works, published by Shinchōsha in 1975.

Christians of all denominations make up only one percent or so of the Japanese population. Despite these small numbers, Endō Shūsaku’s best-known work on a Christian theme, Chinmoku (trans. by William Johnston as Silence), has sold more than 2 million copies and was made into a movie by Martin Scorsese. Besides his serious literary works, Endō also wrote many popular novels marked by humor and gentle irony. His work continues to enjoy critical and popular success around the world.

Endō was convinced that there was an important difference between “human life” and our daily lives of humdrum routine. What was it that made his work so popular across a diverse readership in Japan and around the world, turning him into a globally renowned author who was frequently mentioned as a candidate for the Nobel Prize? Throughout his career, he continued to examine the deeper meaning of human existence, and was never afraid to tackle the serious questions of life and death from a viewpoint that remained profoundly shaped by his Catholic faith. It is surely this combination of seriousness and lightness of touch that accounts for his global reputation and lasting importance in this, his centenary year.

Endō Shūsaku: A Chronology

| 1923 | Born on March 27, in Sugamo, Tokyo. |

| 1929 | His father’s work takes the family to Dalian, China, where he attends school. |

| 1933 | After his parents’ divorce, Endō returns with his mother to Japan. He is later baptized at the Catholic Church in Shukugawa, near Kobe. |

| 1943 | Graduates from Nada Middle School. Enters the Department of Literature at Keiō University three years later. |

| 1949 | Graduates from Keiō with a degree in French literature. |

| 1950 | Travels to France as one of the first postwar cohort of overseas students, enrols at the Universitė de Lyon. |

| 1955 | Wins the Akutagawa Prize for Shiroi hito (White Man), and marries Junko, whom he met as a student at Keiō. |

| 1966 | Wins the Tanizaki Jun’ichirō Prize for his novel Chinmoku (Silence). |

| 1975 | Publication of the Complete Works of Endō Shūsaku in 11 volumes from Shinchōsha. |

| 1993 | Publishes his last novel, Fukai kawa (Deep River). |

| 1995 | Receives the Order of Culture. |

| 1996 | Dies on September 29, at the age of 73. |

Endō Shūsaku, Fukai kawa o yomu: Mazā Teresa, Miyazawa Kenji to hibikiau Sekai

By Yamane Michihiro

Published by The Board of Publications, The United Church of Christ in Japan

ISBN:978-4-8184-1127-2

(Originally written in Japanese.)

Related Tags

religion book review Christianity Miyazawa Kenji Endo Shusaku