“How Do You Live?”: The Classic Novel that Inspired Miyazaki Hayao

Books Education Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

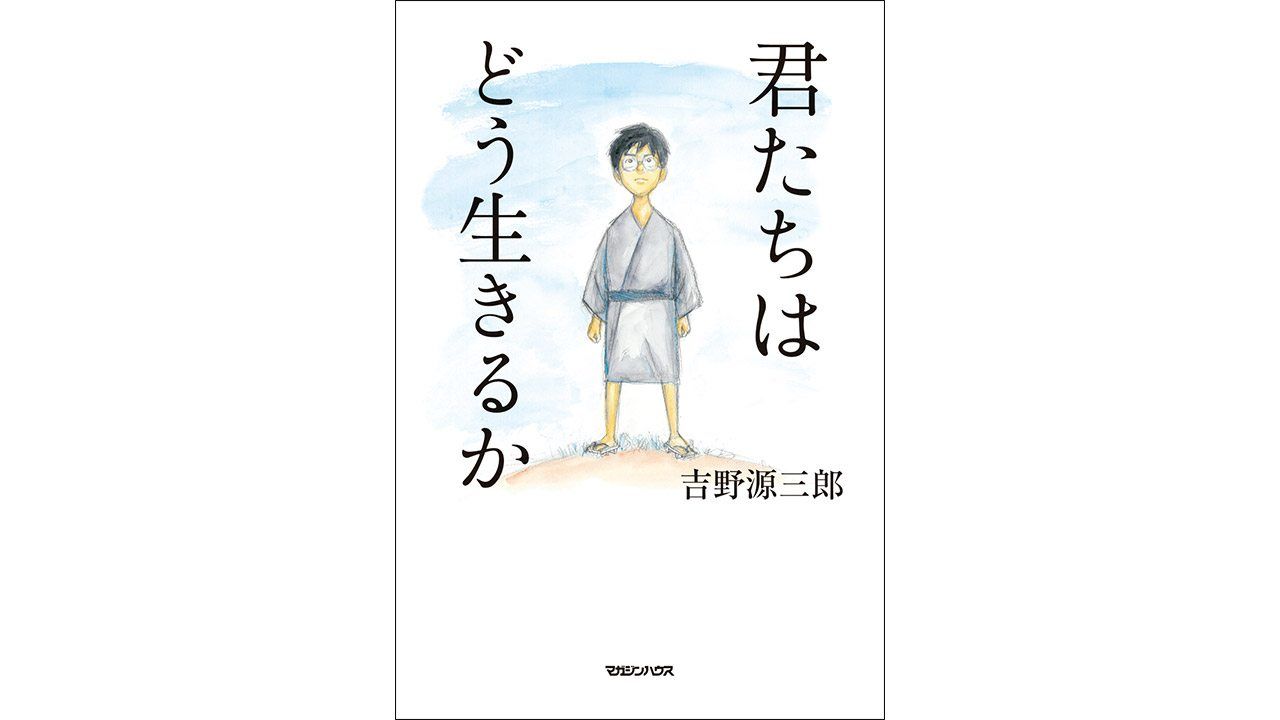

Miyazaki Hayao’s new film The Boy and the Heron takes its Japanese title from the timeless classic Kimitachi wa dō ikiru ka (translated by Bruno Navasky as How Do You Live?). The philosophical novel, first published in 1937, was written by Yoshino Genzaburō, who later started the Iwanami Shinsho nonfiction book series.

It has been popular among successive generations. A 2017 manga adaptation sold more than 2 million copies. And now Miyazaki Hayao’s first full-length animation for a decade is driving further interest in the novel (although the movie is based on an original story by the director). In the more than 80 years since publication, Japan has passed through times of war and economic growth and stagnation. Why has the novel remained so well loved over the years?

Encouraging Thought

The protagonist is a 15-year-old boy called Copper. He is in the second year of junior high school, and as many children of the era went to work after graduating from elementary school, this means he is part of the elite.

Copper is good at his studies and quick-witted, but mischievous. Each day’s events move him to ponder, worry, laugh, and cry. The book recounts his daily activities, interspersed with writings from his uncle’s notebook, addressed to him. A broad range of themes appear, including thoughts on the wealth inequality Copper feels in interactions with a classmate, friendship and conflict with close companions, and what it means to be “great,” inspired by stories about Napoleon.

The uncle takes what he sees through Copper’s 15-year-old eyes as entry points for deft questions about abstract themes, and he inspires consideration in his nephew, and readers too, as the following excerpts show.

[Y]ou absolutely must attend to the things you feel in your own heart, the things that move you deeply. That is what is most important, now and always. Do not forget this, and think carefully about what it means. . . .

If you were to start to feel even a little proud of your family’s good life and to look down on people less wealthy than you, more thoughtful souls would be right to laugh at you. . . .

There’s one [misery] that pierces our hearts most deeply, that wrings the bitterest tears from our eyes. It’s the awareness that we have committed a mistake that we can’t go back and fix.

The book was first published in 1937. That year the Sino-Japanese War broke out; the National Mobilization Law was passed the following year, and 1939 saw the start of World War II in Europe. Japan slid rapidly into militarism.

Naturally, there were many who did not welcome a book that encouraged readers to cherish their own feelings, a sentiment out of step with the growing number of boys and girls drawn by militant patriotism. I wonder what those who got hold of the book or wanted their children to read it were thinking at the time. Stepping away briefly from our present moment in 2023 inspires such imaginings.

A Book to Read Together

When I was in elementary school, our homeroom teacher used How Do You Live? in our ethics class. I remember that we all read up to a certain point and discussed it in the lesson, but I must confess that at around 10, I could barely relate to either Copper’s feelings or his uncle’s way of thinking. I have a bittersweet memory of only being able to make a few noncommittal comments, still unclear of what the book was trying to say.

As I reread it, however, I was constantly finding points of agreement. As though my eyes had suddenly sprung open, I understood Copper’s feelings and what his uncle wanted to convey. This must have been because I had not experienced the same feelings at 10 or I did not recognize them, and I can only understand them now as an adult, when Copper’s uncle’s words hit home.

These feelings include the shame of giving in to a desire to protect oneself by running away from what one should do, the unease of suddenly realizing one is looking down on others, the joy of having days of anxiety wiped away by the single word of a friend, and the brevity and importance of the time spent with friends that one does not notice in the thick of it all.

Reading the novel after experience in the world, the truths that the uncle wants to impart naturally become lessons one wants to pass on to children. This must be how the book has remained popular over the years.

It must be difficult for children to understand, but its importance spurs one on to make the effort. I recommend trying to read it together. Even if adults have moments when they nod in recognition, it does not mean that they are always acting as they should. Instead, every day we think, “It would have been better to do that,” so we are not always in the uncle’s shoes, and cannot forget Copper’s perspective either.

The book ends with an important question to readers, both children and adults, encouraging them to reflect on their actions. “How will you live?”