Watanabe Tsuneo: A New Book Explores a Giant of Journalism and Politics

Politics Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Media and Political Heavyweight

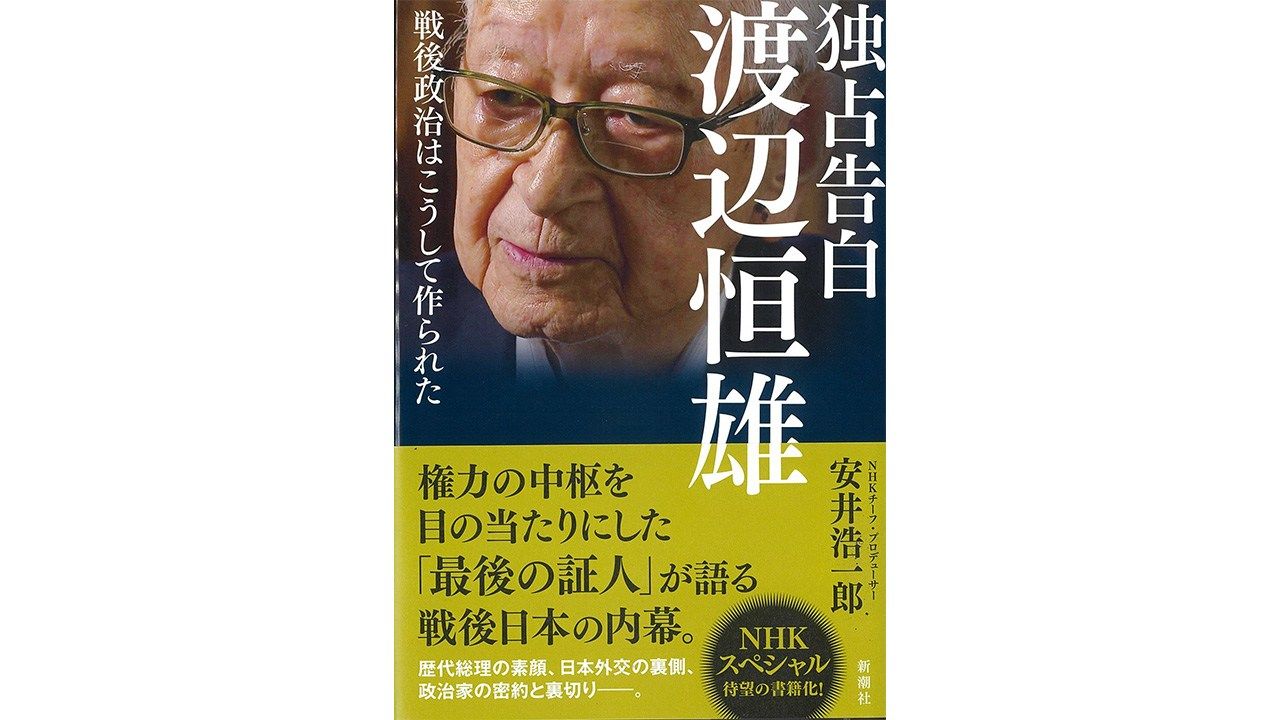

Over a lengthy career in journalism, Watanabe Tsuneo (1926–), now the representative director and editor in chief at Yomiuri Shimbun Holdings, has left behind countless articles and opinion pieces on Japan’s political scene. He has also penned a number of volumes of his memoirs detailing his work. At the beginning of this year, though, a new book—Yasui Kōichirō’s Dokusen kokuhaku Watanabe Tsuneo: Sengo seiji wa kō shite tsukurareta (Watanabe Tsuneo’s Exclusive Confessions: The Shaping of Japanese Postwar Politics)—shed fresh light on what had seemed to be an already thoroughly covered life.

I asked one retired top editor from the Yomiuri Shimbun, Watanabe’s newspaper, what he thought about this work. His reply: “If you want to get a complete picture of Watanabe the man, and his record as a political journalist, warts and all, I’d say this one book should be enough to provide that.”

Yasui Kōichirō was a director of an NHK program consisting of exclusive interviews with Watanabe—his first ever for use in visual media—that was aired in March 2020. In this book, he fleshes out the information shared there with a considerable amount of detail that did not make it on air.

The book features, first of all, Watanabe’s own frank telling of his life story: his youth and upbringing, his experiences in World War II, and his interactions with prime ministers from Yoshida Shigeru (1946–47, 1948–54) up through Nakasone Yasuhiro (1982–87). It also contains observations from eminent scholars and political journalists from Watanabe’s era that build on these first-person statements to present a fuller, objective picture of both the light and dark sides of the subject. With this approach, Yasui does a fine job of preventing his book from becoming simply a vehicle for Watanabe’s own takes.

Watanabe was generally viewed as a conservative thinker, known for advocating the revision of Japan’s “peace constitution,” among other causes. But one thing his statements make clear is that he also had a staunchly liberal streak, a dislike of conflict and military matters rooted in his experience as a student conscript mobilized in the war. After Japan’s defeat he returned to his studies at the University of Tokyo, where his idealism led him to join the Japanese Communist Party. Disillusioned by the excessively militaristic arrangement of that organization, though, he soon left, embarking instead on a more realist path in his thinking.

Upon joining the Yomiuri Shimbun and being assigned to the political department at the age of 26, he found his realist take served him well. He also displayed a talent for connecting with members of the political world. From the late 1950s, he became close to former Prime Minister Hatoyama Ichirō (1954–56). Watanabe recalls how he accomplished this:

“I became a horse. I got down on all fours and played with his grandsons, Yukio [who would go on to be prime minister in 2009–10] and Kunio [who would hold the education, labor, justice, and other portfolios]. I’d give them rides on my back, neighing and whinnying as we went. When their grandfather saw how I got along with the boys, he treated me like a member of the family. I had free run of the house—into the kitchen, into his study. I could go anywhere.”

Watanabe went on to become a close confidant of Liberal Democratic Party power broker and Speaker of the House of Representatives Ōno Banboku, even taking part in back-room deliberations on who would be tapped as members of upcoming cabinets. Ostensibly tasked with reporting on the political world, Watanabe had wormed his way into it and was now one of its key movers.

Mincing No Words

With his deep access to the political world, Watanabe developed a comprehensive understanding of its machinations. This book presents a number of little-known episodes he shared in the course of the interviews. These include the truth about the secret pact forged by Kishi Nobusuke, Ōno Banboku, Kōno Ichirō, Satō Eisaku, and other LDP kingmakers to determine the order in which top party members would take the prime minister’s mantle. Also described are Watanabe’s own behind-the-scenes preparatory work to help bring about the 1965 normalization of Japan’s relations with South Korea; his scoop uncovering the top-secret memorandum between Foreign Minister (and later Prime Minister) Ōhira Masayoshi and Kim Jong-pil, the number-two member of the Park Chung-hee administration in Seoul, that determined the amount of economic aid Japan would offer to Korea; lesser-known aspects of Japan’s negotiations with the United States to secure the 1972 reversion of Okinawa to Japanese control; the lowdown on the creation of the administration of Tanaka Kakuei (1972–74); and much more. Fans of political intrigue will find it hard to put this book down.

Watanabe enters the Kantei, or prime minister’s office, in Tokyo’s Nagatachō on April 5, 2016. (© Jiji)

One of the most rewarding sections covers Watanabe’s ties with his closest compatriot, Nakasone Yasuhiro. Soon after he was first elected to the Diet in 1947, Nakasone began having Watanabe join him for weekly “study sessions” at which they worked together to sketch out Nakasone’s path to the premiership. These passages present episodes relating to Nakasone’s first cabinet posting, Watanabe’s work as intermediary between Nakasone and his archrival Tanaka Kakuei as they laid the foundations for the Nakasone administration launched in 1982, and many other fascinating events in the journalist’s career.

Above all else, though, the book is worth reading for Watanabe’s unvarnished takes on the political world. Take, for instance, the time when he witnessed stacks of cash being handed out to members of the Diet during election season. This was one of the experiences that taught him the truth about the raw, cutthroat world of politics, he recalls: “You’ve got to be realistic about it, or you’ll never get what happens behind the scenes in politics. The way money moves decides everything in this world, and until you get that, you won’t understand any of it.”

On his relationship with Ōno Banboku, he notes: “There are some fools out there muttering things like ‘A journalist reporting on people must never get too close to his subject.’ But you’ve got to get close to them if you want that story. If a politician tells you not to write something and you write it all anyway, he’ll never speak to you again. . . . If you take a hands-off attitude in dealing with politicians, they’ll never tell you the truth. You’ve got to get in tight with them and then squeeze it out of them, bit by bit.”

On the subject of Ōno, he also recalls the time when Kishi Nobusuke broke the secret pact mentioned above, preventing Ōno from becoming prime minister in his turn. “Ōno was in tears. The man seemed indomitable, but at that time he found himself betrayed. Politics is a world where you deceive others or are deceived yourself, and if you’re deceived, it’s your own fault.”

Nakasone, meanwhile, is described in these terms. “Whatever I proposed to him, he’d take it on board and run with it. It made it truly rewarding to offer him advice. . . . There are plenty of politicians who are utterly indifferent to what you say—your words go in one ear and out the other. But Nakasone would actually turn that advice into action, whether it was in diplomacy, domestic policy, or political philosophy. I think that’s what made him the sort of man who went as far as he did.”

This rewarding book covers the vast scope of Watanabe’s career during the Shōwa era (1926–89). One wonders what his relationship was like with Abe Shinzō, who served longer than any other prime minister. We can only hope there will be a follow-up book covering the Heisei era (1989–2019).

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The cover of Dokusen kokuhaku Watanabe Tsuneo: Sengo seiji wa kō shite tsukurareta. Courtesy of Shinchōsha.)

Dokusen kokuhaku Watanabe Tsuneo: Sengo seiji wa kō shite tsukurareta (Watanabe Tsuneo’s Exclusive Confessions: The Shaping of Japanese Postwar Politics)

Related Tags

book review politics media books Yomiuri Shimbun Watanabe Tsuneo