Manga Media and Content in Postwar Japan

Osaka: Where Japanese Manga Began Its Meteoric Rise

Culture Entertainment Manga Anime- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Osaka’s Wholesale District is the Unsung Home of Manga Greats

Manga’s evolution began in what is today Matsuyamachi, in the Chūō ward of Osaka. The area is home to a great many wholesalers of dolls, toys, penny candy, and paper products. But its publishing industry, which played a key role in manga history, is less well known.

A shopping arcade in Osaka’s Matsuyamachi. Currently known as “Gocchamachi,” the arcade is home to many wholesale shops. (© Pixta)

A street scene from 1960s Matsuyamachi. (© Kyōdō)

Tokyo is today the center of Japan’s publishing industry. But in the premodern era of the Edo era (1603–1867), the country had three major centers of publishing: Ōzaka (now called Osaka), Kyoto, and Edo (now Tokyo.) Even in the subsequent Meiji era (1868–1912), the Osaka area remained home to influential publishers such as Tatsukawa Bunmeidō, whose Tatsukawa Bunko imprint published the popular Sarutobi Sasuke series of ninja stories. These publishers clustered in a stretch from the Shinsaibashi district of Minamisenba to Matsuyamachi.

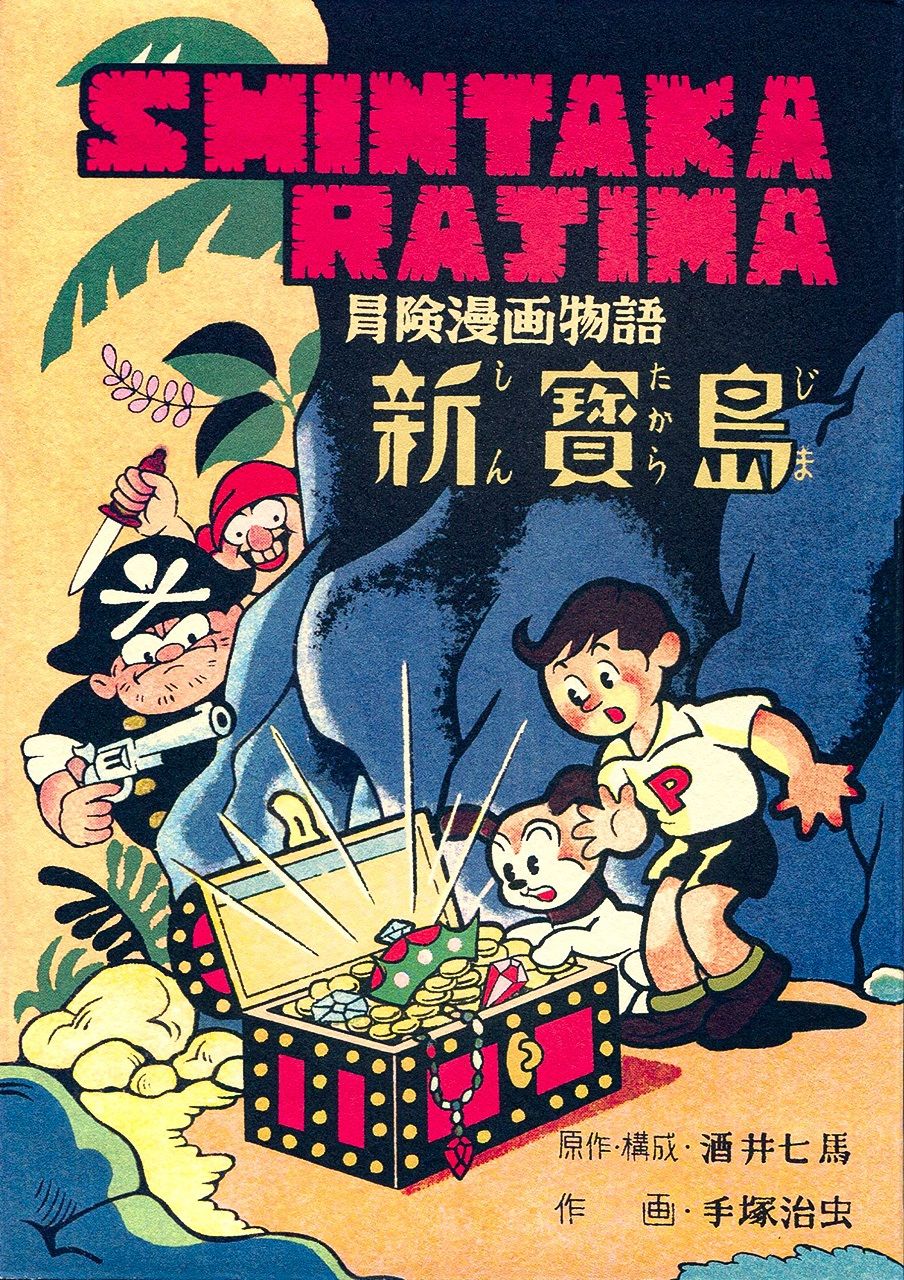

In January of 1947, not long after the end of World War II, Ikuei Shuppansha, a publisher in the neighboring district of Jūnikenchō, released a manga. Illustrated by Tezuka Osamu based on a story by Sakai Shichima, it was called Shin Takarajima (New Treasure Island). Sakai was an industry veteran who had worked widely as a manga artist and animator before the war. Tezuka would later be hailed as the “God of Manga,” but at this time was an unknown student still commuting to classes at Osaka University’s medical school.

Tezuka Osamu’s Shin Takarajima. (Photo courtesy Nakano Haruyuki)

In July of 1946, Tezuka, accompanied by another veteran artist named Ōsaka Tokio, visited Sakai’s home. Sakai and Tezuka hit it off, with Sakai suggesting a collaboration. Tezuka readily agreed, for he had been developing a new style of manga, neither comic book nor novel, ever since his days as a student at Kitano Junior High School (now Kitano High School). So it was that Tezuka came to draw a comic based on Sakai’s storyboards.

The protagonist, a young boy, sets out to find a hidden treasure marked on a map. Along the way, he is attacked by pirates, caught in a storm, and swept away to an unknown island—an island that just so happens to be the one marked on his map! But just as he sets out to explore, the pirates attack again. Inspired by Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel Treasure Island, its wild adventures captured the hearts of Japanese children in the postwar era.

Tezuka often claimed sales of more than 400,000 copies, but given the shortages of paper and printing technology of the era, the true number was more likely in the tens of thousands of copies—still an astoundingly high figure for a children’s manga of the day.

Sparking a Boom for “Story Manga”

Tezuka and Sakai’s work sparked an extraordinary boom in Osaka. In addition to the old guard of publishing companies that had been in business since before the war, small toy companies began publishing manga as well. Many of the authors were young people in their teens and twenties, just like Tezuka. Among them was Komatsu Sakyō, a Kyoto University student who later became a leading figure in the world of science fiction. His megahit Japan Sinks is fondly remembered even today.

This new wave of manga artists introduced characters as complex as any movie, using techniques such as foreshadowing to ratchet up the drama. They eschewed straight good-vs.-evil narratives and did the unthinkable for a comic book in killing off main characters. Tezuka called this new, cinematic style “story manga.”

The reason Osaka manga publishers utilized so many untested artists is because of the tankōbon format, which made it possible to release inexpensive volumes of works collected from more frequently published sources. In Tokyo, manga generally appeared in childrens’ magazines as compilations of numerous short stories penned by veteran artists. Their stranglehold on the market left little room for young up-and-comers. Tezuka’s “story manga” stood out from these simplistic, moralizing stories.

Tokyo manga artists and critics derided Osaka manga as cheap akahon, “red books,” so called because of the cheap red-tinted paper upon which they were printed. Nevertheless, Tezuka, who continued experimenting on his own after going independent from Sakai, succeeded in using them to pioneer an all-new style of narrative illustrated storytelling.

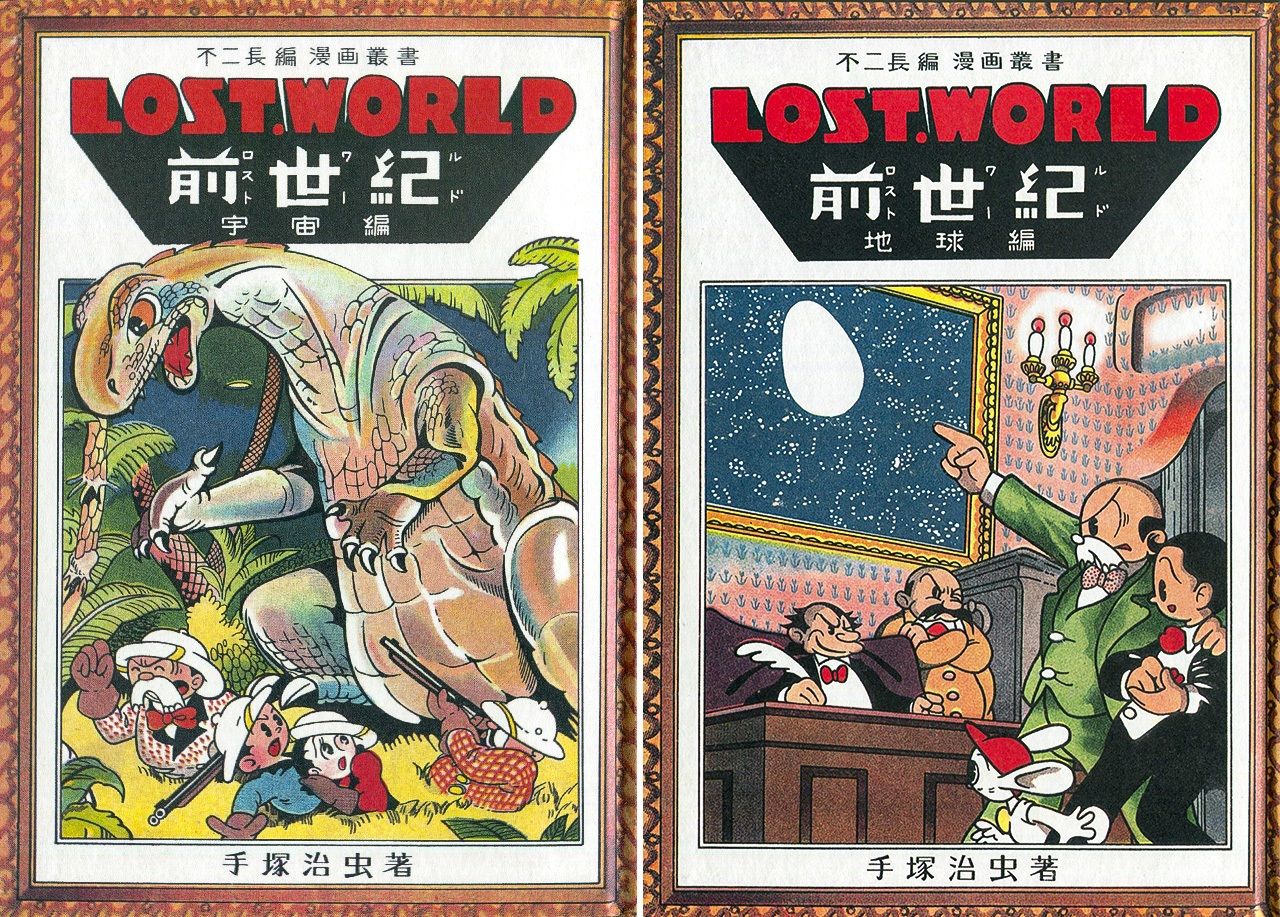

Among them was Lost World, published in two volumes by a company called Fuji Shobō in 1948. This was a long-form work of the sort Tezuka had dreamed of creating since his junior high days. The story involved a rogue planet called Mamango rapidly approaching Earth carrying mysterious “Energy Stones.” The diverse cast included a young scientist, a detective, a band of thieves, and a shady newspaper reporter. The young scientist encounters a girl who is a human-plant hybrid, but the pair are betrayed by the reporter, who strands them on Mamango. The climactic death of Mii-chan, a sentient super-rabbit who plays an important role in helping them return to Earth, shocked young readers of the era.

Tezuka’s Lost World. (Photo courtesy Nakano Haruyuki)

Fujiko Fujio, Ishinomori Shōtarō, and Other National Stars

Tezuka’s story manga spread from Osaka across Japan. In Toyama, they influenced a young pair later called Fujiko F. Fujio and Fujiko A. Fujio; in Miyagi, Ishinomori Shōtarō; in Nara, Umezu Kazuo; and in Fukuoka, Matsumoto Leiji. First contact with Tezuka’s manga transformed their tastes, along with the paths of their careers.

Tezuka began travelling to Tokyo in 1950, when he first serialized his story Janguru taitei (Kimba the White Lion) in the monthly Manga Shōnen magazine. It portrayed the drama of three generations of lions in the jungles of Africa, culminating in a tragic climax where the star Leo dies.

Tezuka moved to Tokyo in 1952 after passing his medical school examinations. A generation of children who adored his work came of age and followed, debuting their own work in Tokyo manga magazines. In this way, story manga spread from Osaka to all of Japan.

New Genres Arise from the Rental Book Scene

In 1956, yet another evolution of manga occurred in Osaka, thanks to a publisher located in the Andōjimachi district of the city’s Minami Ward (currently Chūō Ward). Hakkō, a publisher of kashihon comics for lending libraries, published the very first gekiga, a new genre of “dramatic picture” comics by a group of up-and-coming young authors. The style they pioneered would transform the face of manga in Japan.

At the time, Japan was home to some 30,000 establishments known as kashihon-ya: libraries that lent books and magazines for a fee. These small operations were so ramshackle that many only had dirt floors. They rented out books for ¥10 to ¥20 per day per title. The demand was such that publishers often released books specifically for kashihon-ya, rather than releasing them through regular bookstores. The most popular genre was manga, and Osaka was a major hub for publishing them. In addition to Hakkō, companies such as Tōkōdō, Bun’yōsha, Mishima Shobō, Wakaba Shobō, and Kinryū Shuppansha competed for mindshare, outstripping rivals in Tokyo and Nagoya.

The Osaka kashihon publishers were tiny operations, much smaller in scale than the big names of Tokyo, like Shōgakukan, Shūeisha, and Kōdansha. But they took a much more hands-off approach editorially, giving their writers and artists unprecedented freedom.

Hakkō’s roster included names such as Tatsumi Yoshihiro, Matsumoto Masahiko, Satō Masaaki, and Saitō Takao, a group of young creators who began taking manga in totally new directions. Saitō would go on to create Golgo 13, a nationwide hit, while Tatsumi’s rebellious comics would eventually draw fans in North America and Europe. At the time, though, they were still in their twenties, toiling in obscurity.

Artist Saitō Takao, creator of Golgo 13, died in September 2021. This photo is from a November 2021 exhibition in the city of Sakai, where he lived as a child. (© Jiji)

These rambunctious and ambitious young creators grew up on Tezuka’s story manga, but found themselves wanting something more. Story manga were intended for young boys and girls, with protagonists to match. This resulted in an odd world where child heroes drove cars, carried guns, and fought with swords alongside adult side-characters.

“Films Using Paper and Pen”

Many of the patrons of rental bookstores were young laborers who worked in local factories and shops. Saitō and Tatsumi aimed to create manga that resonated with this generation. Rather than telling stories about children dressed as superheroes, they sought to depict life-sized characters who struggled with realistic dilemmas and experienced inner conflict. In an interview before his passing, Saitō told me, “We tried to make films using paper and pen.”

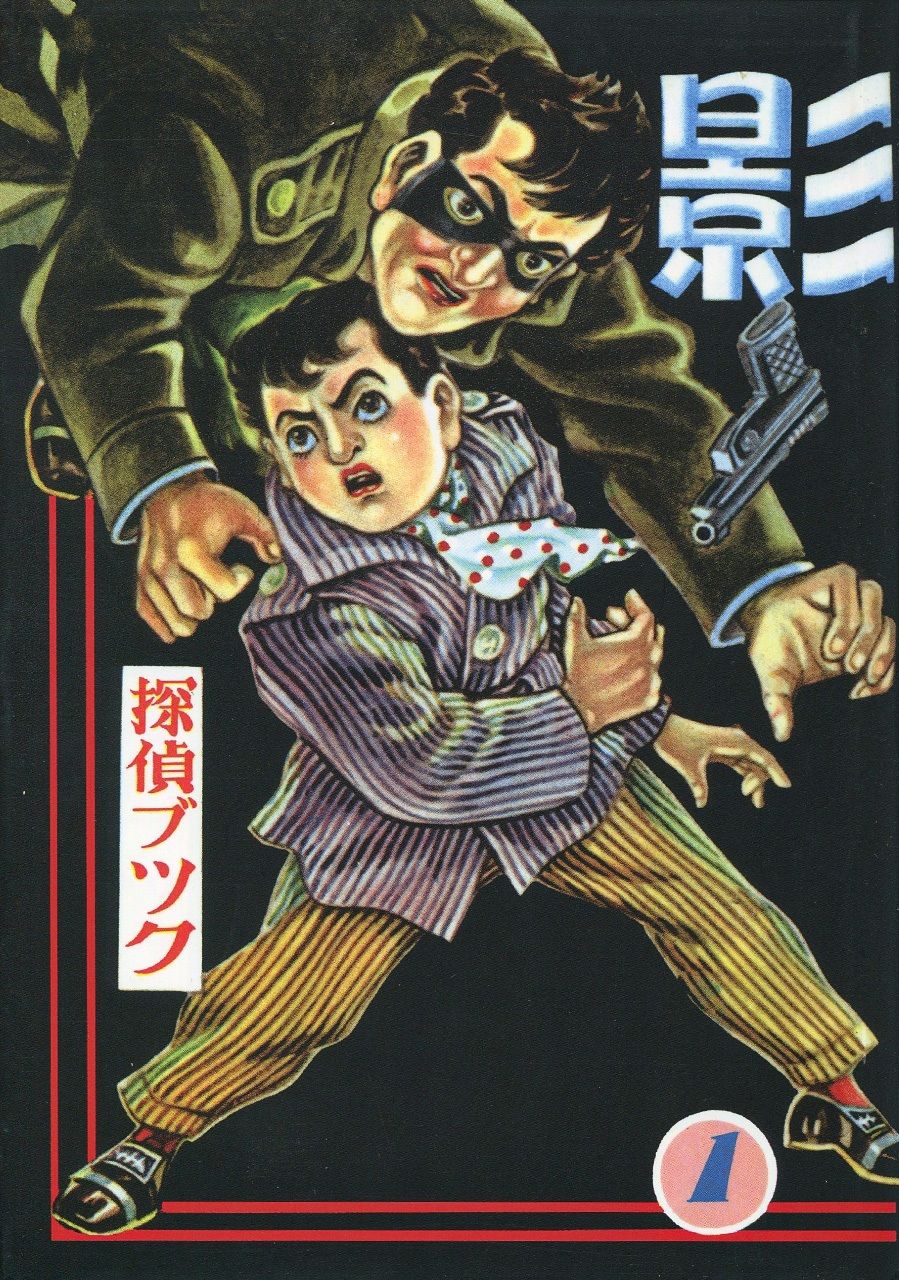

In 1956, Hakkō launched an ambitious compilation of shorts from young artists under the name of Kage, which was published for the rental book market. Creators realized that the term manga did not capture the intent or atmosphere of their creations. Manga was written with characters meaning “fun pictures.” It was the artist Tatsumi Yoshihiro who coined the word that would define this new genre: gekiga, written with characters meaning “dramatic pictures.”

An issue of Kage, a seminal gekiga magazine. (Photo courtesy Nakano Haruyuki)

In January 1959, Tatsumi established the Gekiga Workshop in Osaka. By 1960, its members began moving to Tokyo, setting up in an apartment building in the city of Kokubunji west of the metropolitan center. Inspired by Kage, Tokyo publishers began releasing a wave of rental book anthologies, stoking demand for gekiga-style work.

Initially, children’s magazines shunned gekiga as “too violent” or “crude.” However, they could not ignore the genre’s growing popularity. By 1967, even children’s magazines began serializing gekiga-style stories. In the monthly Shōnen, Saitō Takao launched his spy-action series The Shadowman, while the weekly Shōnen Magazine began publishing his samurai period drama Muyōnosuke.

The Audience Grows

Chiba Tetsuya, the manga artist known for the boxing work Ashita no Joe (Tomorrow’s Joe), described the scene of the time in a 2011 television documentary: “Like a black wave, gekiga surged in from Osaka. With its arrival, it became possible to depict the darker sides of human nature.”

Meanwhile, Osaka’s publishing industry, having lost many of its artists to Tokyo magazines, rapidly declined. By the mid-1960s, it was all but gone. In contrast, the gekiga boom in Tokyo only grew stronger. Magazines targeting young adult readers emerged one after another, including Weekly Manga Action in 1967 and Big Comic in 1968. Gekiga remained at the forefront of this movement; even Tezuka Osamu began taking a gekiga-style approach in his works for young adult magazines.

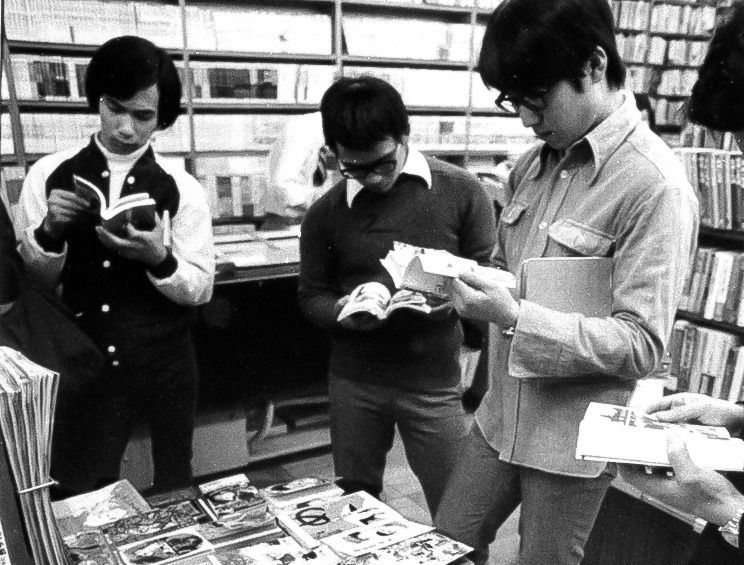

A bookstore in Kanda, Tokyo, at the height of the gekiga boom, in October 1973. Manga began emerging from children’s literature into a full-fledged form of expression for readers of all ages. (© Kyōdō)

Once considered mere children’s entertainment, illustrated narrative entertainment began attracting a broader, and older, audience thanks to the emergence of gekiga. The themes depicted expanded as well, coming to include social issues, politics, gambling, gourmet culture, and medicine, among many others. Gekiga helped manga realize its true breadth and diversity.

Today, terms like story manga and gekiga have all but faded into obscurity. But throughout the 1970s and beyond, the trails they blazed continued to branch in complex ways, ultimately shaping the rich and diverse world of Japanese manga as we know it today.

What-ifs are often futile exercises, but it’s tempting to wonder what would have happened to Japan’s illustrated entertainment had Osaka’s revolutions never occurred. Had they not, Japanese manga—and even anime—might never have gained the global recognition that they enjoy today.

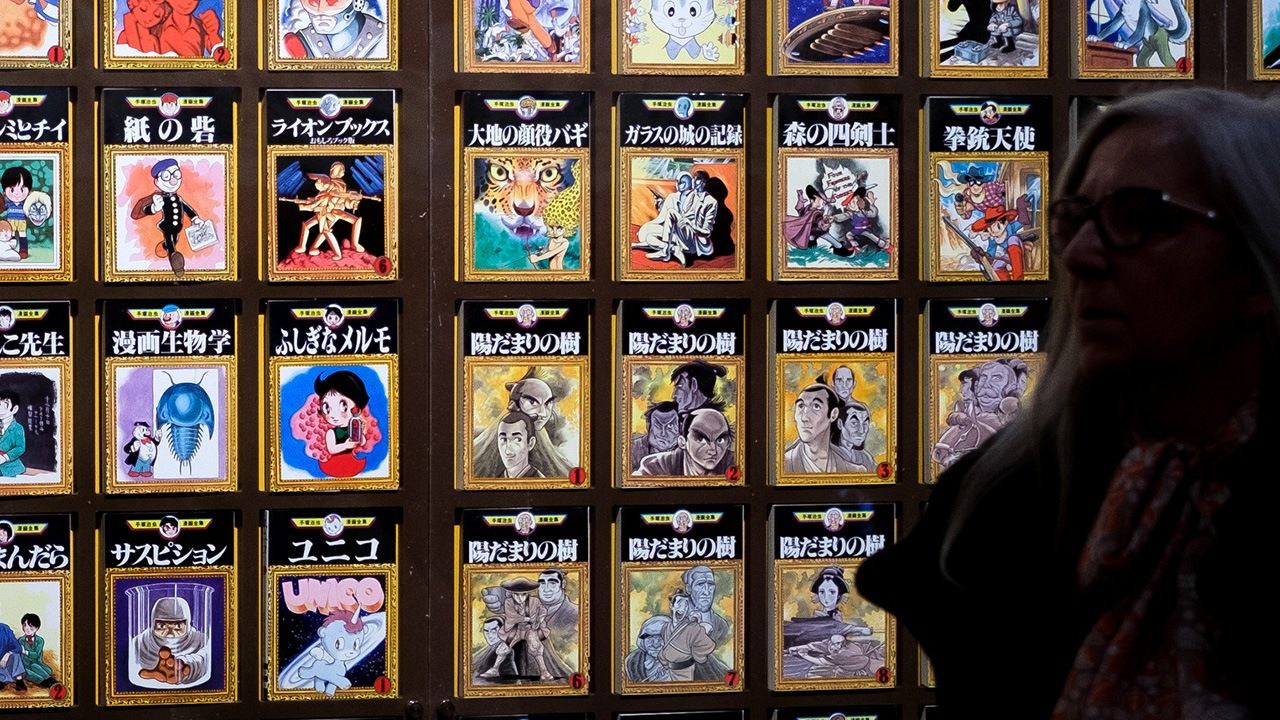

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Works on display at the Art of Manga exhibition, featuring Osamu Tezuka’s work, held in Madrid in April 2024. © Oscar Gonzalez/Sipa USA/Reuters.)