Manga Media and Content in Postwar Japan

Anime or Manga? Examining the Different Hit Formulas in Japan and Abroad

Culture Entertainment Manga Anime- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Anime Adaptations Top Charts

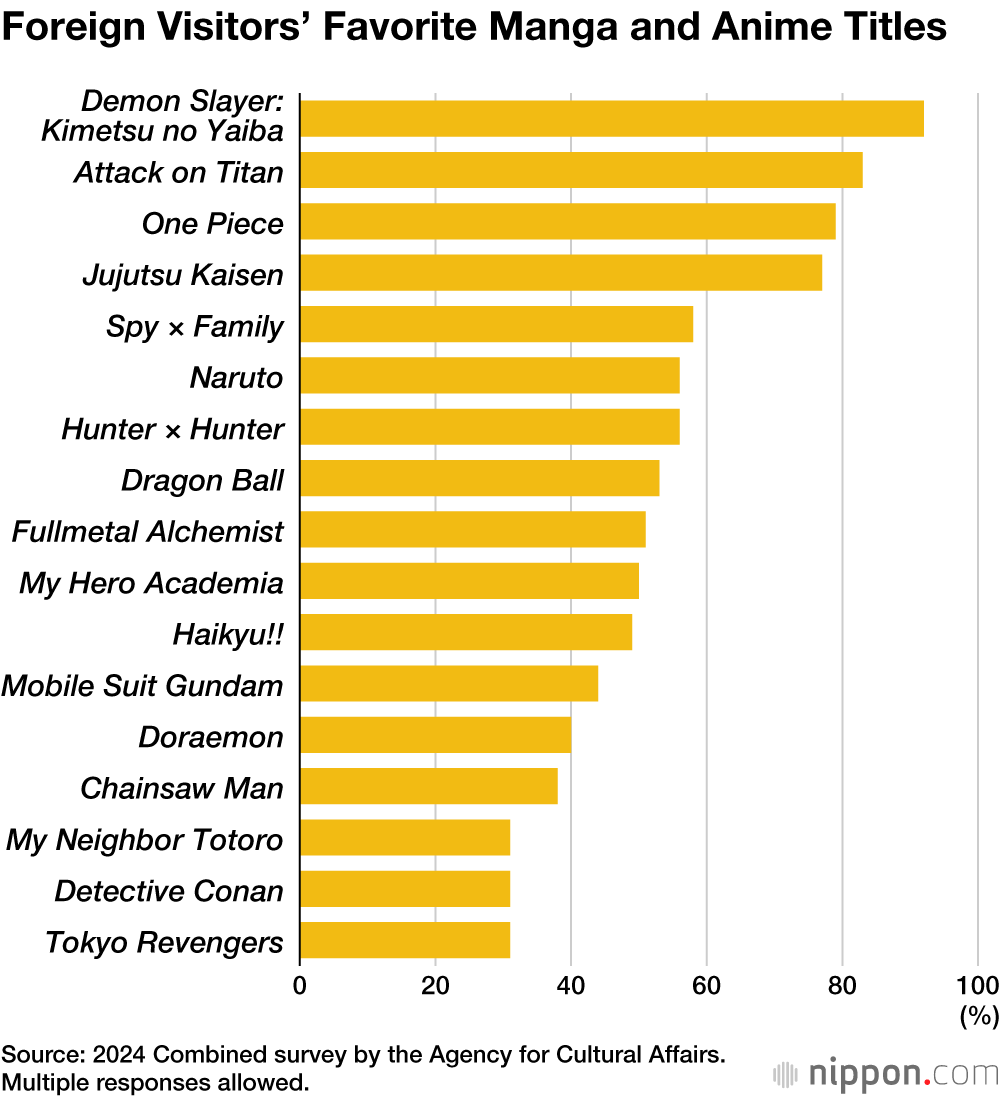

In November 2024, Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs and other organizations released a list of manga and anime titles loved by international visitors in Japan. Starting with the top-ranked Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba followed by Attack on Titan at number two, all 10 titles in the rankings were manga works that had been adapted into anime and introduced overseas.

In other countries, Japanese-style weekly or monthly manga magazines are virtually nonexistent, so people are first introduced to Japanese anime through television, cable TV, or online streaming. It is often only after watching the anime that they pick up the translated manga. This is because anime can be easily enjoyed through accessible mediums.

In 2021, TV Tokyo began streaming anime such as Naruto to Arabic-speaking regions. An advertising still from Naruto Shippūden. (© Kishimoto Masashi /Scott/Shūeisha, TV Tokyo, Pierrot)

Rich Stories That Resonate Across Demographics

Traditionally, overseas TV animation and animated films have primarily targeted children and families. In contrast, Japanese anime appeals to a broader audience, often exploring themes like the essence of humanity, life and death, and war—topics rarely addressed in non-Japanese animations. For instance, Naruto tells the story of the titular struggling ninja, who teams up with friends to restore peace to their world. The narrative follows the lonely protagonist’s growth into a determined ninja pursuing his dreams while portraying diverse traits in both allies and enemies. Such depth owes much to the original manga’s script.

As of December 2024, the top-ranked title for the ”Most Popular Anime” on My Anime List, the world’s largest anime and manga database site, is Attack on Titan. Similarly, this work gained popularity overseas through its anime adaptation, subsequently drawing attention to the original manga.

Attack on Titan made a red carpet appearance at the opening ceremony of the twenty-seventh Tokyo International Film Festival on October 23, 2014. (© AFP/Jiji)

Popularity of Manga Fueled by Anime

The Attack on Titan story takes place in a world where humanity faces extinction due to predations by massive titans and struggles to survive within the towering walls built to keep them out. Beyond the gripping premise of humans becoming prey for giant foes, themes like segregation and hate based on race have also resonated with Western audiences.

In the United States, sales of the first volume of the manga, published in 2012, surged after the anime began streaming online in April 2013. Since then, the manga has been translated for over 180 countries and regions, selling a cumulative total of 120 million copies worldwide by the end of 2023, including sales in Japan.

Japanese manga titles on display in a US bookstore. (© Pixta)

In Japan, it is common for anime adaptations to follow a manga’s success. Overseas, however, manga fans are often first captivated by Japanese anime, which offers a freshness and depth not typically found in their local animation. From there, they discover Japanese manga. The appeal is not “Japanese manga” itself but rather in the animated creations based on the print titles.

The popularity of Slam Dunk in China also began with its anime adaptation. Chinese tourists visiting the famous railroad crossing near Kamakura High School on the Enoshima Electric Railway see it as a pilgrimage site, as the location was memorably featured in the anime’s opening sequence. Similarly, Oshi no ko, which has a large fanbase in South Korea and the United States, owes much of its popularity to its anime adaptation. The opening song, Idol, reached No. 1 on the Billboard Global Excl. US chart in June 2023, further driving the anime’s success.

It All Started with Astro Boy

The first Japanese TV anime to air in the United States was Astro Boy (known in Japan as Tetsuwan Atomu). Broadcast began in September 1963 on NBC. Created by Mushi Production, the animation studio founded by Astro Boy manga author Tezuka Osamu, this was Japan’s first domestically produced long-form TV anime series.

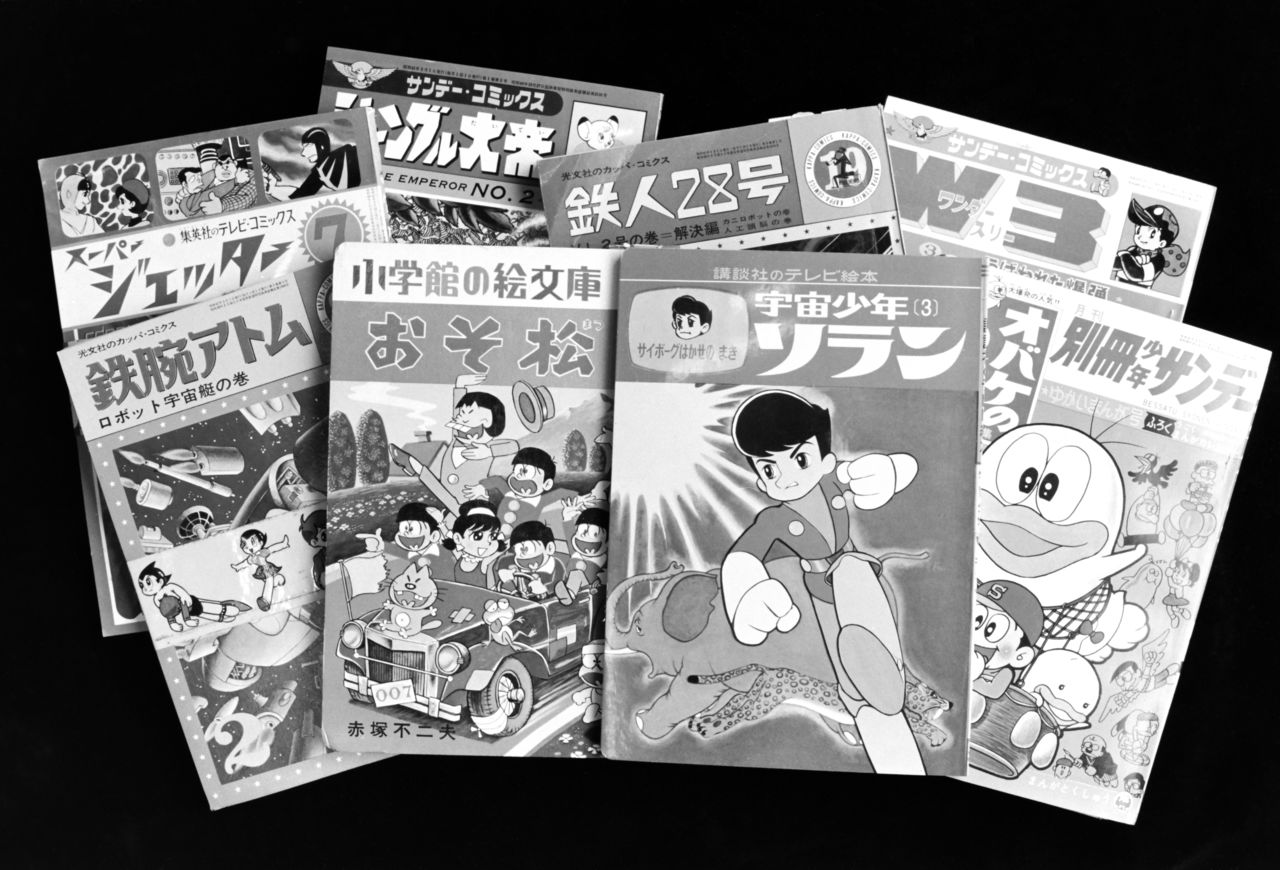

Manga books such as Astro Boy and Space Boy Soran published for children in Japan during the late 1960s. (© Jiji)

Even in this case, awareness abroad followed the pattern of “anime first, then manga.”

Astro Boy is set in a future where humans and robots coexist. It tells the story of Atom, a boy robot who thinks, feels, and acts like a human. After its debut on Fuji Television in January 1963, the show garnered high ratings, sparking a domestic TV anime boom. It was brought to the United States by Fujita Kiyoshi, the president of advertising firm Video Promotion. In an interview with Wedge Online on October 20, 2009, titled “The Man Who Promoted Astro Boy in America,” Fujita recounted the experience in detail.

Fujita envisioned that “anime with no specific national identity could be accepted overseas.” Though met with skepticism by stakeholders, the three major US networks—ABC, CBS, and NBC—showed interest. At local screenings, the response was overwhelmingly positive.

A 2003 ceremony marking the return of the Astro Boy anime to the United States after 40 years, coinciding with the first official release of the manga in the country. (© Jiji)

This success was partly due to the widespread adoption of television in the United States and a shortage of suitable content. In March 1963, Tezuka Osamu himself traveled to New York to finalize a contract with NBC. The anime was subsequently exported through NBC to countries like England, France, West Germany, Australia, Taiwan, Thailand, and the Philippines—all before the manga version of Tetsuwan Atomu was ever translated.

This marked the beginning of widespread exports of Japanese anime. In 1966, the US-Japan coproduction Marine Boy (Ganbare! Marine Kid in Japan) was created. In 1967, Mach GoGoGo aired in the United States as Speed Racer, achieving greater popularity there than in Japan. In 1975, the third entry in the Mazinger series, UFO Robot Grendizer, began airing in France as Goldorak in 1978, becoming a massive hit. It also aired in the Middle East under the title Mughamiratal-Fada: Grendizer.

Robot anime toys displayed at a Paris auction in 2013, including items from UFO Robot Grendizer, known in France as Goldorak. (© Reuters/Charles Platiau)

By the mid-1980s, a wide variety of Japanese anime—including robot sci-fi, fantasy, sports, and culinary stories—was being embraced worldwide. Early international viewers, however, often didn’t recognize these works as “Japanese-made.” Many parents in the United States had served in World War II, so the Japanese origins of the content being watched by their kids were downplayed at the time.

Full-Scale Publishing from the 1980s

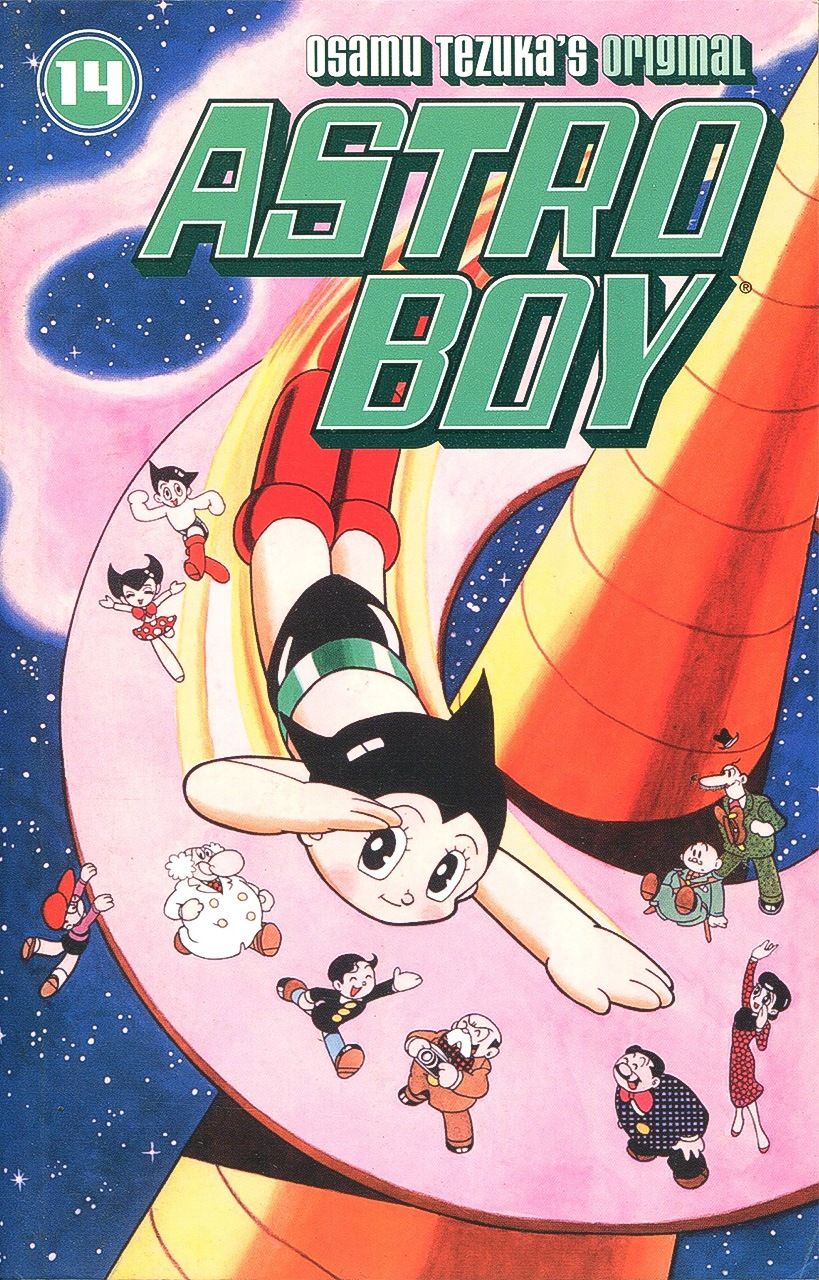

The full-scale translation of manga volumes began in the 1980s, initially in Asia and expanding to Europe in the 1990s. However, Japanese publishers were reluctant to venture overseas due to steady domestic demand and the high costs and logistical challenges involved. For instance, the Astro Boy manga published in 1987 was an unauthorized edition and performed poorly in sales. It wasn’t until 2003 that a legitimate edition was released in the United States by Dark Horse Comics.

The 14-volume Dark Horse edition of Astro Boy released in the United States. (Photo courtesy Nakano Haruyuki)

The turning point for Japanese manga in the United States came with Tokyopop’s English version of Sailor Moon in 1998. The company, based on the West Coast, stopped altering the manga to read from left to right, instead preserving the original Japanese format. Released at an affordable price during a time when fans were clamoring for reruns of the anime, it quickly gained popularity. Tokyopop also expanded Japanese manga, especially shōjo titles, to France and Germany.

Despite Astro Boy making its US debut as an anime in the 1960s, it took over 30 years for its translated Japanese manga to gain significant attention. This delay can be attributed to several factors, including the absence of a Japanese-style manga magazine culture overseas, the complexity of right-to-left reading, and the relative simplicity of anime as a medium. Fundamentally, the lag in manga’s popularity abroad can be traced to the tendency for manga volumes to follow in the wake of anime adaptations.

Could this formula change? Publishers like Shūeisha have begun releasing English versions of manga through apps, often simultaneously with their Japanese releases. There are also new initiatives using artificial intelligence to translate manga for simultaneous distribution online.

While anime currently remains the dominant force in introducing Japanese content abroad, simultaneous manga releases could eventually allow overseas readers to discover the original works before the anime adaptations. This might pave the way for a new cycle where distribution leads to volume releases and ultimately to anime adaptations in international markets.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner Photo: Japan Expo in Paris. The July 2024 event showcased manga, cosplay, anime, and video games, drawing large crowds. © Stephane Mouchmouche/Hans Luca.)