Japanology: Deep Dives into Daily Life in Japan

Little Beauties: The Goldfish Bringing a Splash of Color to Everyday Life in Japan

Culture History- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Aquatic Attractions

Goldfish are perennially popular pets. Attractive and easy to look after, they are a regular fixture not only in schools and homes, but in doctors’ waiting rooms, reception spaces in office buildings, and in small businesses in shopping streets up and down the country. According to a survey carried out by the research company Intage, goldfish and other aquarium fish were Japan’s third most popular pets in 2024, behind only dogs and cats.

With their flowing fins, distinctive head bumps, and protruding eyes, goldfish can be unmistakable. Their striking fins show remarkable variety—sometimes fluttering like butterflies, at other times full and plump like petals. There’s something soothing about watching them in their bowls—a sense of tranquility that seems to ease the strains of daily life.

Perhaps the best way to enjoy goldfish is to watch them from directly above, so that you can observe the continuous, delicate motion of their restless tails and fins as they swim. They come in a rainbow of colors, including red, orange, white, black, silver, and gold. It’s no wonder so many people are captured by their graceful, elegant movements.

A variety of aquarium ornaments lends color and variety to the tank where the goldfish live. (© Pixta)

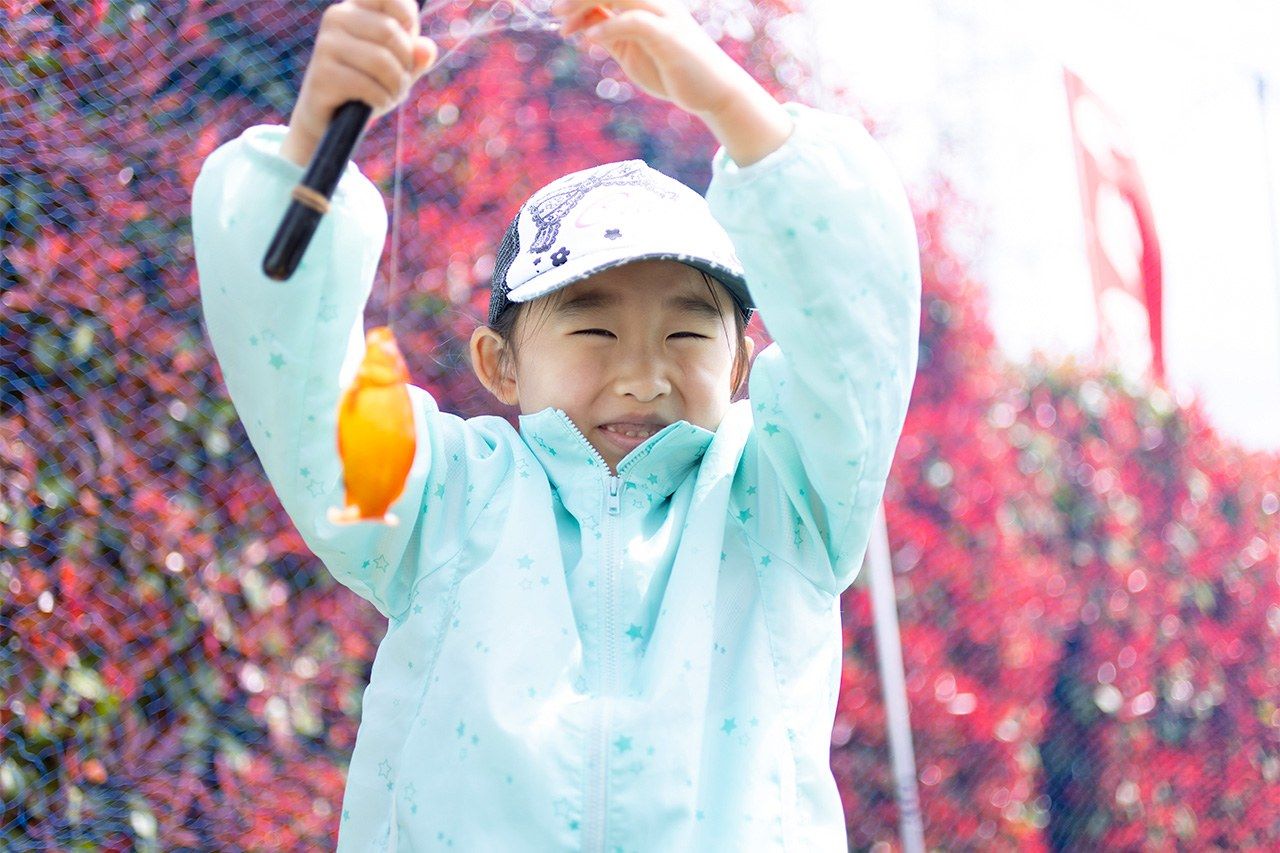

Fishin’ for Gold

During the Edo Period (1603–1868), goldfish were so popular in Japan’s cities that people made their living by selling them. Even today, walking around Tokyo, you can come across fishing ponds where you can pay a small fee and while away an hour or two catching goldfish. One well-known example is Suzuki-en in Suginami, Tokyo. Just a few minutes from JR Asagaya Station, Suzuki-en is an old-timer in the business, having celebrated its centenary in 2024. On weekends and holidays, the pond draws people of all ages—some alone, others on dates or with the family—all sitting patiently with their poles held hopefully in the water. Goldfish have become an essential part of everyday Japanese culture and scenery.

Tokyo is home to numerous goldfish ponds where people of all ages can try their hand at fishing and maybe take home a new pet or two as a prize. (© Pixta)

Festival Standby

A beloved fixture at festivals or matsuri across Japan is kingyo-sukui (goldfish scooping), a game in which children (and adults) compete to catch goldfish with small scoopers made from plastic and paper. The delicate scooper often breaks quickly, adding a layer of skill and excitement to the game. The idea is to catch as many fish as you can before the thin paper in your scooper tears; any goldfish you catch are yours to take home as a prize. For many, these festival-won goldfish become treasured pets and cherished memories of summer.

In recent years, kingyo-sukui has become a popular year-round activity, with specialist facilities where people can make reservations outside of festival season. Competitions are held in various parts of the country, where battle-hardened enthusiasts pit their skills against each other and keep the tradition alive.

Kingyo-sukui, or goldfish-scoping: not as easy as it looks! (© Pixta)

Poetry in Motion

In recent years, goldfish have been elevated to the status of art. The Art Aquarium Museum Ginza opened in Tokyo’s best-known high-end shopping district in 2022. The museum’s displays are dominated by goldfish of all descriptions, the delicate creatures presenting a beguiling sight as they swim through the fantastic displays, beautifully lit by creative and artistic illumination.

Goldfish are the main stars of this artistic display at the Art Aquarium in Ginza. (Courtesy Art Aquarium Museum Ginza)

From China to Edo

When did goldfish become part of everyday life in Japan?

Goldfish originally came from China. It is thought that the first goldfish came to human attention around 2,000 years ago, when someone discovered a naturally occurring reddish specimen among a wild population of crucian carp (funa). The species was domesticated and bred in captivity. Over the generations, natural and human selection did the rest. Goldfish were probably first brought to Japan at the beginning of the sixteenth century, toward the end of the Muromachi Period (1333–1568). Initially, they were rare and exotic creatures that fetched extremely high prices, and keeping them was a hobby reserved for nobility and the wealthy elite.

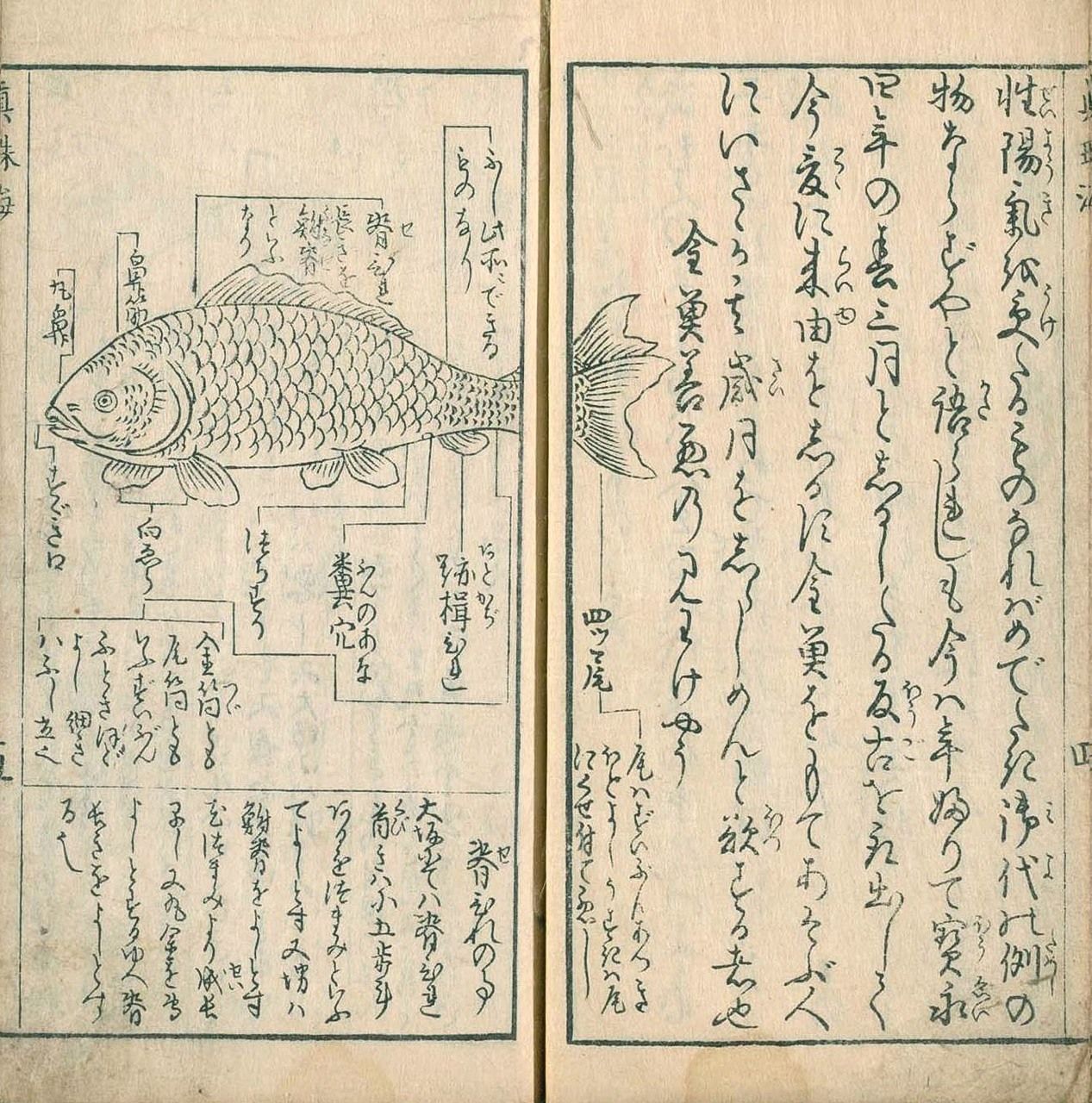

Kingyo sodate-gusa (How to Keep Goldfish), published in 1748. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

It was during the Edo Period (1603–1868) that goldfish became truly popular. Breeding of the fish in captivity took off from the eighteenth century, making them affordable to ordinary people for the first time. The streets of Edo echoed with the calls of vendors carrying buckets filled with goldfish, and Kingyo sodate-gusa (“How to Keep Goldfish” became an early publishing success.

Goldfish in Literature and Art

The Edo period was marked by an explosion of culture among the urban masses, particularly the townspeople (chōnin), as books, woodblock prints, and popular theater flourished like never before. Goldfish frequently featured in the fiction and ukiyo-e prints of the time, as they became a familiar part of the everyday urban landscape.

For instance, a late eighteenth-century print by the ukiyo-e artist Kitagawa Utamaro, famous for his pictures of beauties, depicted a teahouse courtesan holding goldfish in a glass bowl. The writer Ihara Saikaku, who chronicled life in the pleasure quarters, also included goldfish in several of his works. Even the cultured intellectuals and artists of Edo, it seems, were falling under the spell of these beautiful, colorful fish as they swam gently through the water.

“The Goldfish Lover,” h1401 Utamaro Toyokuni’s 24 Paragons of Modern Beauty, 1863. (National Diet Library)

Following the major boom of the Edo period, breeding goldfish became a popular sideline for cash-strapped samurai and their lords. The practice continued among farmers after the Meiji Restoration. Over time, the fish and the culture surrounding them became an integral part of Japanese life, adapting to the changing landscape.

Variety and Color

Some people have suggested that the Japanese enthusiasm for goldfish might be linked to something in the Japanese character—the same tendency to appreciate small objects of beauty in everyday life that can be seen in cultural practices like bonsai and ikebana.

Goldfish come in a staggering number of varieties. These include the familiar wakin—the common variety used in kingyo-sukui—the oranda shishigashira (Dutch Lionhead), with its distinctive bulbous head, the ryūkin (flowing gold) with its brightly colored tail and fins, and the demekin or “telescope,” a variety related to the ryūkin but distinguished by its strikingly protuberant eyes.

Ryūkin. (Courtesy of Art Aquarium)

Not all varieties originated in China. The “ping-pong pearl,” named for its distinctive shape, comes from Southeast Asia, while the Comet, a natural mutation of the ryūkin, developed in the United States.

Ping-pong pearl. (Courtesy of Art Aquarium)

Around 30 Hybrids Made in Japan

Around 30 varieties of goldfish have been developed in Japan through hybridization and breeding. The ōsaka ranchū variety, which lacks a dorsal fin and head bump, has pompom-like markings on its face that can look a little like a mustache. This variety nearly went extinct during World War II but was revived after a successful breeding program.

Ōsaka ranchū. (Courtesy of Art Aquarium)

One highly sought-after variety is the tosakin (curly fantail) from Kōchi Prefecture in Shikoku, believed to have been created in the Edo Period as a hybrid between the ōsaka-ranchū and the ryūkin. Its large tail fin spreads wide on both sides, with the outer edges curling forward and downward. The tosakin has been designated a natural monument by Kōchi Prefecture, an honor it shares with the jikin in Aichi Prefecture and the nankin variety in Shimane Prefecture.

Jikin. (Courtesy Art Aquarium)

Nankin. (Courtesy Art Aquarium)

Another Japanese hybrid is the shubunkin, known for its complex patterns featuring multiple colors, including red, white, black, and asagi (light navy). The variety has long tail and fins, giving it an impression of elegance and grace. The edo-nishiki (Edo brocade) has a round body and short fins. It has a small lump on its head and is colored with a rich mix of red, black, and asagi.

These varieties, developed in Japan, have also found their way overseas, with the first export of Japanese goldfish to the United States occurring in 1878. Even in China, the original home of the domesticated goldfish, the number of fish available for purchase dwindled almost to nothing in the 1970s following the Cultural Revolution. Japan played a crucial role in the recovery of the industry, with breeding programs and genetic improvements based on Japanese-bred varieties helping to restore the population in the decades that followed.

According to information from sources in Yamatokōriyama in Nara Prefecture, one of the country’s major centers of goldfish breeding, there are several key points to bear in mind when keeping goldfish: don’t overfeed them, don’t place too many fish in a small tank, and don’t change the water too often. The experts recommend changing about one-third of the water at a time, twice a month during the summer and once a month in winter. The ideal amount of food is as much as the fish can eat in about five minutes; any longer, and it’s probably too much.

A quick trip to a home supplies center is enough to collect everything a budding goldfish enthusiast needs: a tank or goldfish bowl, aquatic plants, and lights. Many shops offer everything together as a convenient starter kit. Lots of enthusiasts choose to make their tank into a feature of their home interior—combining different types of aquatic plants or dramatically lighting the tank to highlight the elegance of the fish swimming inside.

Generally, goldfish are said to live for 10 to 15 years, though the Guinness World Record is an impressive 43 years, held by a wakin named Tish who belonged to a husband-and-wife team in Britain. But in Japan, goldfish are more than just pets. They’re a part of everyday life, a tradition of elegance that shows no sign of fading even after hundreds of years.

(Originally published in English. Banner photo: Goldfish bring a touch of elegance to people’s homes in aquariums and tanks. © Pixta)