A Walk around the Yamanote Line

Walking the Yamanote Line: A New Way to Discover Tokyo

Travel Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Walking Around the City

On Saturday, October 19, 2024, hundreds of people will take part in the fifteenth Tokyo Yamathon, a charity walk along the JR Yamanote train line. Organized by the International Volunteer Group, this event gives participants a chance not only to test their legs and stamina but also to support both domestic and international causes. Since its inception, the Tokyo Yamathon has raised an impressive ¥55,000,000.

This year, all proceeds will be donated to three outstanding organizations: the Tokyo-based NPO Waffle, the Tochigi Conservation Corps, and the Japan Children’s Hospice Association. These organizations are committed to promoting gender equality in tech, preserving the environment, and providing support to children with life-limiting conditions and their families. The event typically sees around 1,000 participants each year and is open to teams of two to four members of any nationality.

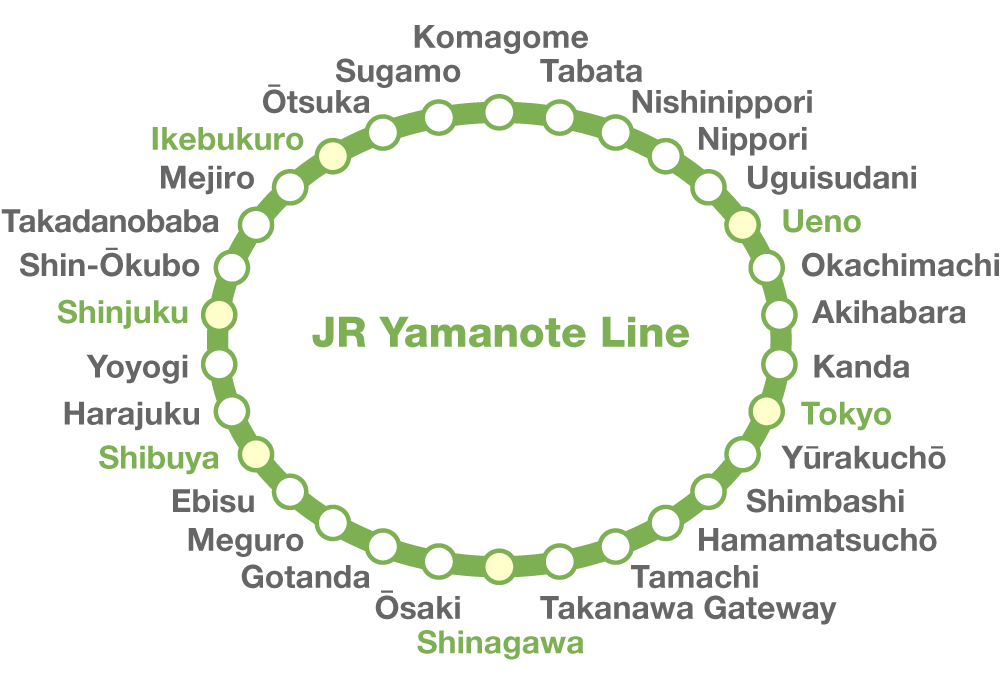

The stations on the Yamanote line stations loop. (© Pixta)

Covering between 38 and 44 kilometers in one day, over a maximum of some 12 hours (depending on which route you take), may not be everybody’s idea of having fun. Besides, keeping too close to the railway makes for a rather dull proposition. However, walking around the Yamanote and exploring the districts on both sides of the tracks is a different way to know Tokyo better, as the line touches both popular spots and less known corners of this sprawling metropolis.

Both residents and visitors take advantage of Tokyo’s superb train and subway systems to reach their destinations. These are undeniably convenient and relatively cheap ways to go shopping in Ginza or Shibuya, check out the otaku scene in Akihabara, or relax in a park in Shinjuku or Ueno. But what about the places in between?

After losing its old factories, the waterfront near Tamachi Station has become a much-sought residential distict for wealthy Tokyoites. (© Gianni Simone)

Fresh Discoveries on Foot

In the last few decades, the culture industry has promoted Tokyo as a youthful, dynamic, futuristic metropolis. The ordinary face of the city—its less celebrated areas—are constantly upstaged by an endless stream of spectacular extravaganzas. This, however, does not mean that the ordinary is dull or empty of value; it only means that it hides in the shadows, waiting to be rediscovered by intrepid walkers and curious urban explorers.

Each manifestation of the ordinary (quiet residential alleys, secluded temples and gardens, local shopping streets) may be small, but taken together, they form a large puzzle that is more representative of Tokyo than the Skytree or tourist-clogged spots like Asakusa.

A Yamanote line passes near the scramble crossing outside Shibuya Station. (© Pixta)

As urban analysts like to say, Tokyo is somewhat smaller than the sum of its parts. Its districts and neighborhoods are not harmoniously integrated. Each one preserves its character and peculiarity, and like a mosaic, the overall picture is textured, imperfect. What better way to compare each piece by visiting them one after another, using the railway as your guide?

For example, you can get off at Ōsaki—a recently redeveloped area full of high-rises, but also a few ancient temples hidden on the hill—then follow the Meguro River (lovely all year round, but especially during the cherry blossom season) and walk along the Old Tōkaidō road on your way to Shinagawa Station.

Between Gotanda and Ōsaki, a forest of high-rise condos surrounds both sides of the Meguro River. (© Pixta)

The Yamanote Line seems to be made specifically for urban exploration. On average, in a beeline, only one kilometer separates one station from the next, so that whenever you get tired, you can easily hop on the train. But as I said, the whole purpose of a walk is to make detours and take your time, savoring each place at your own pace.

When exploring Tokyo, we have to completely rethink how to approach the urban environment. If you find the soul of a city in its urban design and architecture, then Tokyo can be disappointing, even soulless. But if you take the time to go off the beaten path and stick your nose into its hidden corners, like the Showa-era houses near Ōtsuka, the pan-Asian enclaves around Ikebukuro and Shin-Ōkubo, or the new residential districts on the waterfront, you will find the true heart of the city, sometimes even in crumbling buildings and dirty backstreets.

This Shōwa-era Tokyo townscape can be found only a short walk from Ōtsuka Station. (© Gianni Simone)

Indeed, Tokyo encourages deep-dive incursions into seemingly unremarkable places. Compared to many major Western cities, for instance, there may not be many sizeable parks and gardens, but close to the Yamanote loop there are three big, parklike cemeteries in Yanaka (south of Nippori Station), north of Sugamo Station, and in Zōshigaya (southeast of Ikebukuro) where you can look for famous people and do some birdwatching on the side. Behind shop fronts and tall buildings are narrow alleys decorated with colorful potted plants and tiny shrines surrounded by age-old trees. Like Murakami Haruki’s parallel worlds, beyond the noisy, traffic-congested main roads lie cozy and intimate rural-like settings where life is lived at a slower pace.

The beautifully landscaped Somei Cemetery near Sugamo Station is also a meeting point for birdwatchers and local pensioners. (© Gianni Simone)

The tiny shrine Kishimojin at Zōshigaya, between Mejiro and Ikebukuro stations. (© Pixta)

Narrow alleys decorated with colorful potted plants in the Nezu area southwest of Nippori. (© Pixta)

Adventures to Sharpen the Senses

The best way to truly know a city is to experience it through the senses. As the writer and urban planner Charles Landry explains in The Art of City Making, cities are sensory, emotional experiences. The urban experience deeply affects our psyche, and one of Tokyo’s most charming features are its different soundscapes. Sounds are pervasive and their social connotations influence our perception of the space of everyday life.

Already in the early twentieth century, Japan’s rapid industrialization had brought the major sonic feature of “noise pollution” to Tokyo and other major Japanese cities. Even today, riding the Yamanote from Shibuya to Shinjuku or Ikebukuro or Ueno, one hardly notices the difference. They all share the same raucous and annoying (often technological) sounds of everyday noise.

However, walking gives us a chance to follow in Lafcadio Hearn’s footsteps and appreciate the changing sounds around us. Already in 1898, Hearn described Japanese sensory culture and their attention to environmental sounds. In the essay “Insect Musicians” he wrote that “Surely we have something to learn from the people in whose mind the simple chant of a cricket can awaken whole fairy-swarms of tender and delicate fancies.”

Nagai Kafū’s novels and short stories, which envisioned the geisha world, are full of the melancholy sound of the shamisen. Those sounds are much rarer now, having been mostly replaced by the romantic tunes of the ubiquitous pianos that take pride of place in many living rooms. But a lone shamisen (or a temple bell, or the voice of a Buddhist monk reciting a sutra) can still be heard when spending lazy afternoons roaming the alleys of more traditional neighborhoods like Nezu or Yanaka, near the Yamanote’s Nippori Station. They carry an ancient, comforting message and establish a connection with the past.

Like Kafū—the accomplished Tokyo flaneur—the best thing you can do is choose a neighborhood, observe and hear, seek traces of the past, and see how they either harmonize or clash with the present.

The Maruya Hakimonoten store near Shinagawa Station, along the old Tōkaidō, is a traditional footwear shop that opened in the Meiji period (1868–1912). (© Gianni Simone)

Walking around Tokyo is the best way to experience not only its ever-changing look and sounds but also its varied smellscape: incense burning, seasonal flowers, the sea breeze coming from Tokyo Bay, or the food stalls leading to Bentendō, the Buddhist temple in Ueno Park. “Too often,” Landry says, “urban stimuli induce a closing . . . of our senses.” We increasingly approach the world within a narrow perspective, and the widespread use of smartphones and headphones further limits our awareness of the things around us. Again, technology-free walking gives us a golden opportunity to practice our senses and reconnect to our surroundings.

The Sugamo Togenuki Jizō temple, filled with the scent of burning incense. (© Pixta)

Discovering the Details of an Impossibly Large City

Going beyond topography, urban exploration is a chance to delve into chorography—at least the way it is defined by the British author and researcher Paul Devereux in Re-Visioning the Earth: approaching “space as experience, place as a trigger to memory, imagination, and mythic presence.”

Tokyo openly, shamelessly, even cheekily, puts on display the overlapping layers of different architectural styles and materials, austere wooden shrines happily coexisting with arrogant ferroconcrete skyscrapers and musty old houses kept together with rusty panels of corrugated iron. The overall effect is a reminder that history is not just a simple progression but rather a layering of accumulated influences.

The centuries-old Tokaiji Ōyama cemetery, between Ōsaki and Shinagawa Stations, lies wedged between the Shinkansen, the Yamanote, and the Keikyū lines. (© Gianni Simone)

Borrowing what Michael Moorcock said about London, we can say that Tokyo is a city that lives in memory and human activity. Its districts are structured less by their geography and architecture (in Japan, after all, all buildings are seen as transient and disposable) than by what people do. Forget monuments’ cumbersome presence. Memory is all in the stories that hover through Tokyo streets, altered, enhanced, distorted by urban myths, and often locked up in place names.

Taken in its entirety, Tokyo is inscrutable, undecipherable, and at times alienating. But if we cut it into more digestible pieces, we begin to discern patterns, features, and local character. To some people this impossibility to grasp the total personality of Tokyo can be frustrating. But it can also be extremely exciting. It makes for a more intriguing and charming urban experience, especially if you like to poke around some of its lesser-known corners, like Jewelry Town in Okachimachi or the restaurants hidden in the bowels of the Yamanote in Yūrakuchō.

The Sanchoku dining area, near Yūrakuchō Station, is hidden directly under the Yamanote tracks. (© Gianni Simone)

In the end, Tokyo invites and rewards curious walkers who are not afraid of leaving the main road to make detours on a whim; who prick up their ears and sniff out hidden wonders, both literally and metaphorically.

(Originally written in English. Banner photo: a scene from the Yamathon. Courtesy of the International Volunteer Group.)