Tokyo’s Forgotten Dengue Panic

Health Environment Science- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Tropical Disease in the Big City

In 2014, like something out of a disaster movie, Tokyo became the site of a tropical disease outbreak. On August 25, a teenage girl was admitted to hospital complaining of fever and pain throughout her body. After a biopsy analysis performed by the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, the woman was diagnosed with dengue. Two other students from the same school were also infected. None of the three had been overseas—rather, they caught dengue after being bitten by mosquitoes while engaging in extracurricular activities in Yoyogi Park, which is situated in central Tokyo.

The 2014 dengue outbreak made the headlines, being Japan’s first in around 70 years. Hosting a variety of events, Yoyogi Park is visited by over 5 million people every year, and is located near the commercial districts of Shibuya and Harajuku. In response to the incident, the Tokyo Metropolitan government closed the park, sprayed insecticide, and removed water from fountains in a bid to reduce mosquito numbers.

A worker sprays insecticide in Yoyogi park to prevent dengue in 2014. (© Jiji)

More cases followed, with a total of 19 prefectures, spanning as far north as Aomori and as far south as Kōchi, reporting cases of dengue in the two-month period through October 15. A total of 162 people were infected nationwide, 108 of them in Tokyo—but luckily, none with serious symptoms.

Dengue is spread by the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) and the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti), which inhabit tropical and subtropical climates. Humans are infected when the dengue virus enters the body via mosquito saliva, and the virus is passed on when a mosquito feeds on the blood of an infected person and then bites another human. I myself caught dengue once, in Thailand. Beginning with a rapid-onset fever, my symptoms progressed to headaches and nausea, and I came out in a rash. Dengue is also known as “break-bone fever” for the unbearable joint pain that it causes.

Dengue has been known to humankind for over a thousand years, with the earliest records stretching back to tenth-century China. During and after World War II, the disease spread to the Philippines and Thailand, and later to the rest of Southeast Asia. Eventually, dengue even reached the United States. Japan was the scene of outbreaks in Kobe, Osaka, and Hiroshima during World War II, with some 200,000 cases reported, after the virus was brought back by soldiers returning from Southeast Asia. Yoyogi Park hosts many international festivals with Asian and South American themes, so it is possible that the virus was brought in by a visitor from one of those regions.

The last 20 years have seen a global uptick in dengue. According to the WHO, around 500,000 cases were reported in the entirety of 2000, but in 2024, 8 million cases had already been reported by May, in around 130 countries. The disease is particularly prevalent in Vietnam, Bangladesh, Thailand, and other parts of Asia, although only 0.06% of cases are fatal.

One reason for the rise in the incidence of dengue is the emergence of mosquitoes conferred with a “super resistance” to insecticide. Japan’s NIID says it takes 1,000 times the usual dose of pyrethroids to kill superresistant mosquitoes. The active ingredient in mosquito coils, pyrethroids have traditionally been extremely effective against mosquitoes. Superresistant mosquitoes are believed to be the result of a genetic mutation.

New York and West Nile Virus

West Nile virus, a disease endemic to Africa, was reported in a residential area of New York City on August 23, 1999. Eight people were taken to hospital complaining of encephalitis symptoms including fever and severe headache, of whom seven died. Some 59 more cases, in patients aged 5 to 95, were later recorded in New York. The New York City Department of Sanitation stated that the cases were acute West Nile virus encephalitis.

The disease later spread to the rest of the United States, including Washington DC. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of the end of 2023, a cumulative total of 59,151 people had been infected with West Nile virus since data started being collected in 1999, of whom 2,958 died. Now endemic in the United States, West Nile virus is the leading cause of encephalitis, a disease in whose onset many viruses are implicated. There is no vaccine for West Nile virus, and it is estimated that a total of approximately 7 million have been infected in the US, although 80% of cases were asymptomatic. The pandemic later spread to Canada, and Central, and South America.

At the same time that Western Nile virus patients were showing up in New York City hospitals, the streets of New York were littered with the bodies of hundreds of crows. Later, reports emerged of mass deaths of wild and captive birds, and even pet horses, causing panic among residents. West Nile virus was isolated from the dead animals, and epidemiologists established that the virus had been spread from these animals to humans.

West Nile virus belongs to the same family as Japanese encephalitis. It is carried by yellow fever mosquitoes and Asian tiger mosquitoes, which feed on the blood of birds and then pass the virus onto humans. West Nile virus was found in over 220 bird species in the United States, including crows and sparrows. How the virus managed to infiltrate a big city like New York is a mystery, although before the New York outbreak, outbreaks were recorded in Israel and Tunisia, and it seems likely that the virus was brought in from one of those countries.

Mosquito Migration

According to the American Veterinary Medical Association, the wild animal that causes the most human deaths is the mosquito. As such, this insect remains at the top of the list of the world’s ten most dangerous animals, far ahead of poisonous snakes and sharks. Every year, 1 million deaths worldwide are attributed to mosquito-borne viruses. And let us remember that even Alexander the Great, who succumbed to malaria, was no match for a single mosquito. Noguchi Hideyo, a bacteriologist who was well-versed in mosquito ecology, also died of yellow fever, which is carried by the yellow fever mosquito.

The yellow fever mosquito is particularly nasty, as it is a vector for not only for yellow fever, but also dengue, West Nile virus, and several other viruses, none of which have a cure. But just how did tropical mosquitoes from tropical climates appear in the middle of a big city as far north as Tokyo in the first place? The answer: cities are full of receptables suited to holding stagnant water and supporting mosquito larvae, such as empty cans, tires, stagnant ditches, and blocked drains. In days past, visitors to Japanese graves would place 10-yen coins in vases so that copper ions would dissolve in the water, preventing mosquito larvae from hatching. This wisdom was not passed down, unfortunately.

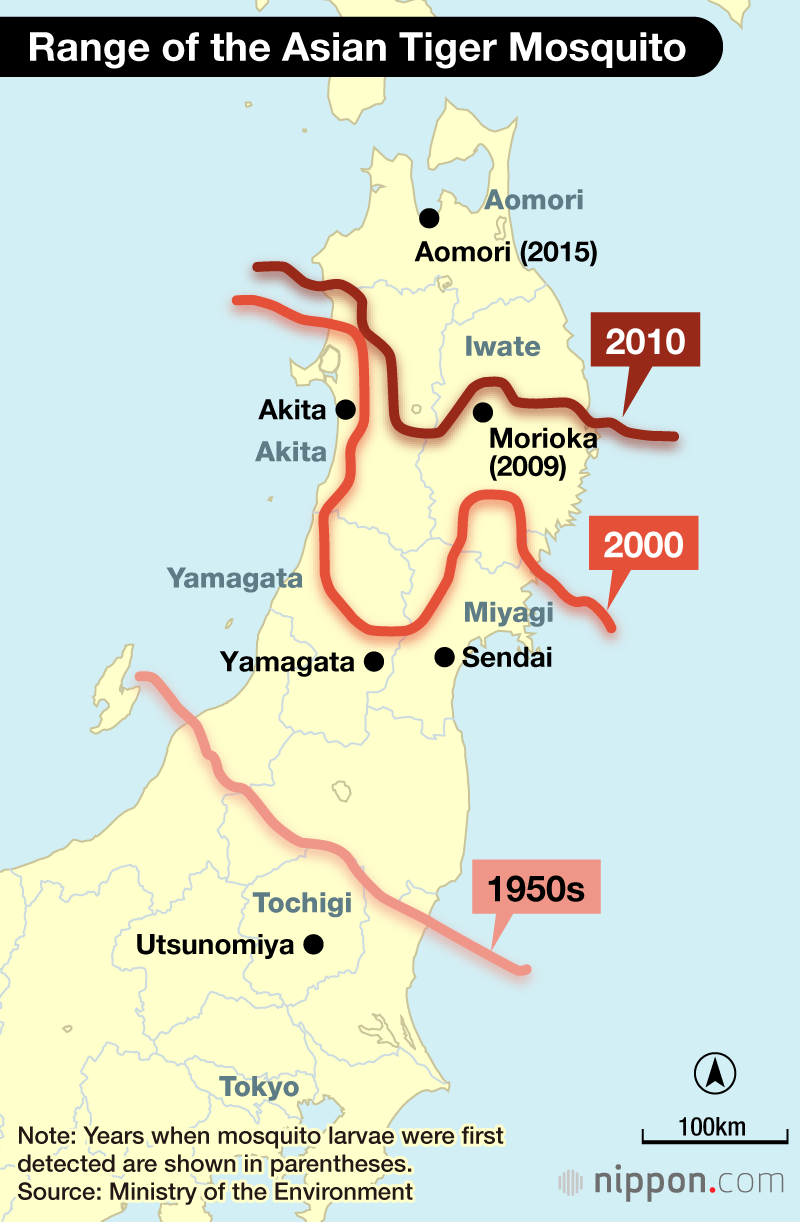

What’s more, thanks to the emergence of urban heat islands, Japanese cities are now even more mosquito-friendly. Cases of mosquito-borne diseases used to peak between mid-July and early September, but in recent years, cases are being recorded as late as December. There is obviously also a need to consider the effects of global warming. According to the Ministry of the Environment, the range of the Asian tiger mosquito that carries dengue more or less corresponds to the zone that has an average temperature of 11°C or above. Continued global warming therefore looks likely to further increase the mosquitoes’ range.

In the 1950s, the northern limit of the range of the Asian tiger mosquito was defined as the prefectures of Fukushima, Tochigi, and Ibaraki. By 2010, however, the mosquitoes were being sighted in Akita and Aomori. While Asian tiger mosquitoes have yet to be observed in Hokkaidō, a Ministry of the Environment report projects that the species will reach the northernmost prefecture by the year 2100.

A Warning for the Future

According to Simon Anthony, an emerging infectious disease specialist at the University of California at Davis, the approximately 5,400 pathogenic viruses that have been recorded to date are only the tip of the iceberg. Each of the earth’s approximately 62,000 vertebrate species harbors endemic viruses. According to Anthony, on the basis of this number, there could well be 3.6 million different viruses out there. There is therefore no shortage of potential pathogens for causing animal-borne illnesses.

When asked whether we could ever see another pandemic like the Spanish flu, Robert Webster, an authority in influenza research and former director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Center on the Ecology of Influenza Viruses in Lower Animals and Birds, replied that it was question of “not if, but when.”

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: The Asian tiger mosquito is a vector for dengue. © Paul Starosta/Getty Images.)