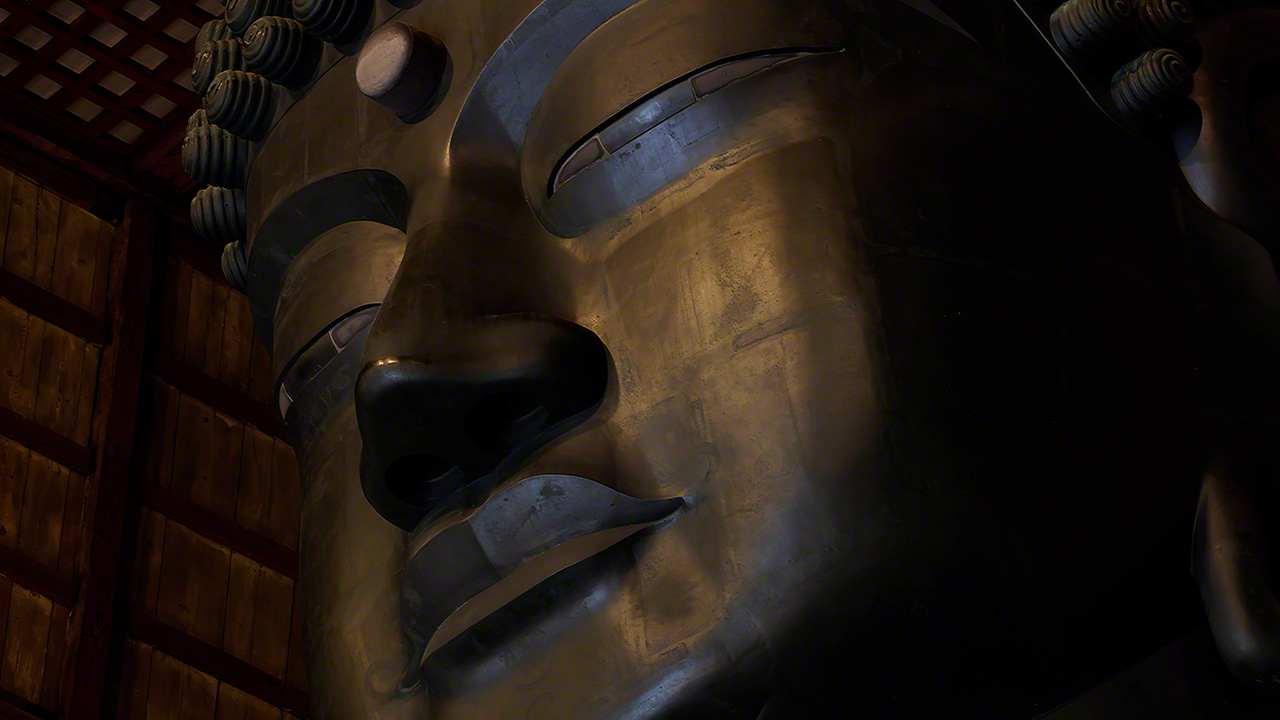

Vairocana, the Great Buddha of Tōdaiji, Nara

Culture Arts- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

The sheer size of the Great Buddha of Nara inspires a sense of awe in everyone who sees it. More than a millennium after it was made, the colossal statue is a proud symbol of Nara and one of the best-known and most beloved examples of Buddhist sculpture in Japan.

Officially known as Rushana-Butsu, or Vairocana Buddha, this the largest bronze Buddhist statue in the world, standing some 15 meters tall and weighing an estimated 250 tons. The chief image enshrined at the temple Tōdaiji in Nara, the Great Buddha was built around 1,300 years ago on the command of Emperor Shōmu (701–756; r. 724–749) to pray for peace and tranquility throughout the realm. Built at a time of state sponsorship of Buddhism, the temple and its image would originally have stood as symbols of political and religious power in what was then the national capital. Today, Tōdaiji remains the head temple of the Kegon (Huayan) sect of Mahayana Buddhism, which reveres the Avatamsaka Sutra, or Flower Garland Sutra (known in Japan as the Kegonkyō), in which the Vairocana Buddha is depicted as the cosmic Buddha at the heart of the universe.

The mudras, or hand positions, of Buddhist images carry symbolic meaning, often expressing key aspects of the Buddha’s teachings. Two important mudras can be observed in the Great Buddha. In the Abhaya mudra (semui-in in Japanese), the Buddha holds one hand to his chest with the palm facing outward toward the viewer. This gesture symbolizes reassurance and safety, representing the Buddha’s power to dispel fear and offer protection to all living beings. The second, the Varada mudra (yogan-in in Japanese), is characterized by the palm held upward and the hand extended outward. This mudra represents the bestowing of blessings, and is a gesture of generosity. It symbolizes the Buddha’s readiness to listen to the deepest prayers and wishes of those who seek his guidance. Together, this common combination of mudras signifies the Buddha’s boundless compassion for all living things.

(© Muda Tomohiro)

The giant image was made by melting down bronze and pouring the molten metal into casts. The alloy used amounted to approximately 500 tons of copper, 2.5 tons of mercury, and 440 kilograms of gold, and casting the statue took nine years to complete.

At the time, Japan hardly mined any gold of its own, and the officials in charge of the project initially planned to import large amounts of the precious metal from the continent. However, during the creation of the image, new gold seams were discovered in the Oda district of Mutsu Province in the far north (now part of Miyagi Prefecture). Emperor Shōmu received news of the discovery as miraculous proof that his grand project had the blessing and protection of the gods and buddhas. In gratitude, he changed the era name to the short-lived Tenpyō Kanpō (wondrous treasures of the blessed peace), before abdicating to take tonsure as a Buddhist monk. An amalgam of gold in quicksilver was applied to the image as gold plating, so that—as hard as it is to imagine from the statue’s present appearance—the entire surface of the Great Buddha would originally have shimmered with glittering gold when it was completed.

The official ceremony to “open the eyes” of the Great Buddha was held on the ninth day of the fourth month in the year 752. The official account in the Shoku-Nihongi chronicle describes the ceremony as “the most glorious event seen in this land since Buddhism arrived in the east.” The cloistered emperor Shōmu himself took part in the religious ceremonies, leading a retinue of military leaders, courtiers, and government officials. Ten thousand monks took part in a grand celebration of music and festivities to celebrate the completion of this monumental national project.

The important task of drawing the Great Buddha’s eyes with a calligraphy brush was entrusted to Bodhisena, an Indian monk who had established the Kegon school in Japan. The brush he used still exists and is among the precious items in the collection of the Shōsōin treasure house, which is administered by the Imperial Household Agency.

(© Muda Tomohiro)

The Great Buddha Hall was destroyed by fire during wars in 1180 and again in 1567, and the Great Buddha image also suffered serious damage. The present head of the Buddha dates from the Edo period (1603–1868). The rest of the torso, from the abdomen to the feet, along with the lotus petals of the pedestal, are original survivals from the Nara period.

(© Muda Tomohiro)

At the Buddha’s feet are 28 lotus petals, each carved with depictions of Shakyamuni (the historical Buddha) surrounded by 22 bodhisattvas. Below them are expansive depictions of the three realms of existence and Mount Sumeru (Shumisen), the mythical mountain at the center of the universe in Buddhist cosmology. These engravings undoubtedly depict the boundless universe of Buddhism as described in the Flower Garland Sutra. Overlooking the entire cosmos is the Great Buddha—Vairocana himself.

An original hairline engraving, carved into one of the lotus petals at the base of the Great Buddha. The engraving shows Shakyamuni preaching the law to a crowd of bodhisattvas. In Kegon Buddhism, the historical Buddha is regarded as a manifestation of Vairocana, the Great Buddha. The high position of the lotus petals means they cannot be seen by visitors, so replicas are displayed at ground level. (© Muda Tomohiro)

Vairocana’s brightness illuminates untold worlds, guiding all living things to enlightenment and salvation. As the source of cosmic light and truth, it is perhaps only fitting that the Great Buddha of Nara was built on such a scale that it can still take the breath away more than 1,300 years later.

The present Great Buddha Hall (Daibutsu-den) was completed in 1706 after its predecessor was destroyed by fire. The Great Buddha was exposed to the elements for some time before the new hall could be completed. (© Muda Tomohiro)

Rushana-Butsu (Great Buddha or Vairocana Buddha)

- Height: 14.98 m

- Date: Nara Period (710–794), with later repairs

- Tōdaiji (Nara Prefecture)

- National treasure

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Vairocana Buddha at Tōdaiji, the famous “Great Buddha” of Nara. © Muda Tomohiro.)