Addressing Social Issues Where Art and Welfare Meet

A Hospital with Heart: Transforming Pain into Hope with the Power of Art

Health Arts- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Art Evokes Communication

Zentsūji is an ancient temple in modern-day Kagawa Prefecture, birthplace of the great Buddhist master Kūkai. Nearby is Shikoku Medical Center for Children and Adults, formed through the amalgamation of Zentsūji Hospital and Kagawa Children’s Hospital in 2013.

The hospital’s exterior walls are painted with colorful trees, and a large white tree-like artwork stands in the entrance to the children’s ward. It is possible to pass through the trunk of the tree, providing playful respite for children who feel stressed in the waiting room. Signage for the elevators incorporate standard pictograms into a steam train design, with a rail line leading the way.

A tree-like artwork by Kawashima Morihiko in the waiting room is designed to help children with developmental disabilities cope with the inevitable waiting that comes with visiting the doctor. (© Kodera Kei)

A train playfully guides people to the elevators. (© Kodera Kei)

Artwork at hospitals tends to be chosen to create a soothing environment. At the Shikoku Medical Center, though, it is immediately apparent that the art on display is not simply for viewing, but is intended as a medium to evoke communication.

Creative Process Conscious of Those Facing Hardship

For the hospital’s art director, Mori Aine, the essence of installing art in the medical environment is a creative process based on dialog. She asks patients and employees to share their concerns and troubles, which she frames as “pain.” Mori then considers the best way to remediate this pain through objective dialog and cooperation from artists, transforming it into hope with art that allows for free interpretation. “It’s important to collaborate with a large number of people,” Mori explains. “Observing pain from multiple perspectives reveals the best path to take.”

Hospital art director Mori Aine. She is also a guest associate professor at the Takarazuka University School of Nursing, director of NPO Arts Project, and co-head of Art Meets Care. (© Kodera Kei)

The impetus for Mori’s appointment as the hospital’s art director was the production of murals for the facility’s predecessor, Kagawa Children’s Hospital.

Mori was active as a photographer while also employed to source artworks for medical facilities. She was approached by the hospital director, who was concerned that the adolescent ward’s psychiatric department felt gloomy, and asked her to develop murals to brighten it up. Patients, their family members, and hospital staff suggested that she paint camphor trees, which are the city’s emblem tree.

Mori spent four months developing the concept, conducting interviews with the concerned parties, and the work was completed in around six months thanks to the assistance of local volunteers. The production process engendered feelings of attachment and pride. Children out of frustration had previously made holes in the walls, but this stopped. Even the ward’s nurses began to appear more relaxed. The impact was greater than expected, and Mori was invited to manage the new hospital’s art from the planning stage.

Exterior view of the Shikoku Medical Center for Children and Adults. The murals of young trees and colorful foliage are based on those painted along corridors by patients and carers at the Kagawa Children’s Hospital. (© Kodera Kei)

Mori’s recommendations for art installation are strongly influenced by her personal experience of suddenly losing her husband to a heart attack. As she struggled with what she describes as “hellish pain,” she continued to photograph their two young children with the camera her husband left behind. Over time, she found that it gradually eased her suffering. “Photographic expression gave me a place where I belonged even amid my conflict and suffering,” she says. “The field of art accepted me as I was and eventually gave me the hope to live.”

The walls of the Home Support and Daycare Center were white but staff and center users with the help of artist Masuda Hisako helped to turn it into a vibrant space. (© Kodera Kei)

Treating Pain with Art

Walking through the center, visitors encounter art that expresses a sense of kindness. Learning the background of each work imparts an even greater understanding of the feelings of the people involved in their creation.

There are small wooden houses in the garden in front of the hospital. Nearby is a sign that reads “Please do not walk on the lawn, it is home to little people. Only some people can see the little people.” The sign was installed after foot traffic began to take a toll on the grass. As with other works at the facility, the sign and small houses deter an unwanted behavior and create a space that delights younger patients.

The houses of the “little people” on the hospital’s front lawn are the work of artist Hayabuchi Taisuke. (© Kodera Kei)

Small house-shaped alcoves have been built into the walls at 19 spots throughout the hospital. Some of these have wooden doors that open to reveal handicrafts and cards with messages, made with the help of some 200 volunteers, that patients may take home.

Alcoves in the wall create a talking point with the patients. (© Kodera Kei)

Children enjoy opening the little doors to discover what hides inside. (© Kodera Kei)

One of the alcoves is linked to a particular girl who was a patient at the facility. A stuffed toy placed next to her pillow by a nurse gave her courage to face surgery, but she was saddened when she had to return the toy later. In response, she started making toys for children awaiting surgery.

However, she was slightly conflicted as she wanted to help others but preferred to remain anonymous. Mori came up with the idea of an alcove where the girl could hide her gifts. Later, another shy girl began donating misanga bracelets that she knotted herself. This led to her gradually opening up and she continued making the gifts even while battling her own illness.

According to Mori, “Invisible interaction that takes place through artistic endeavors provides people with the power to live another day.” Her office is brimming with handmade gifts from volunteers. Patients and medical staff are welcome to visit her at any time. She says that when they share their troubles with her, it provides ideas for future art projects.

Handmade gifts line the shelves in Mori’s office. (© Kodera Kei)

Expressing the Feelings of Medical Staff

Of the many art projects Mori has worked on, she says that a mural for the corridor from the underground mortuary to the carpark had the greatest impact on her perception.

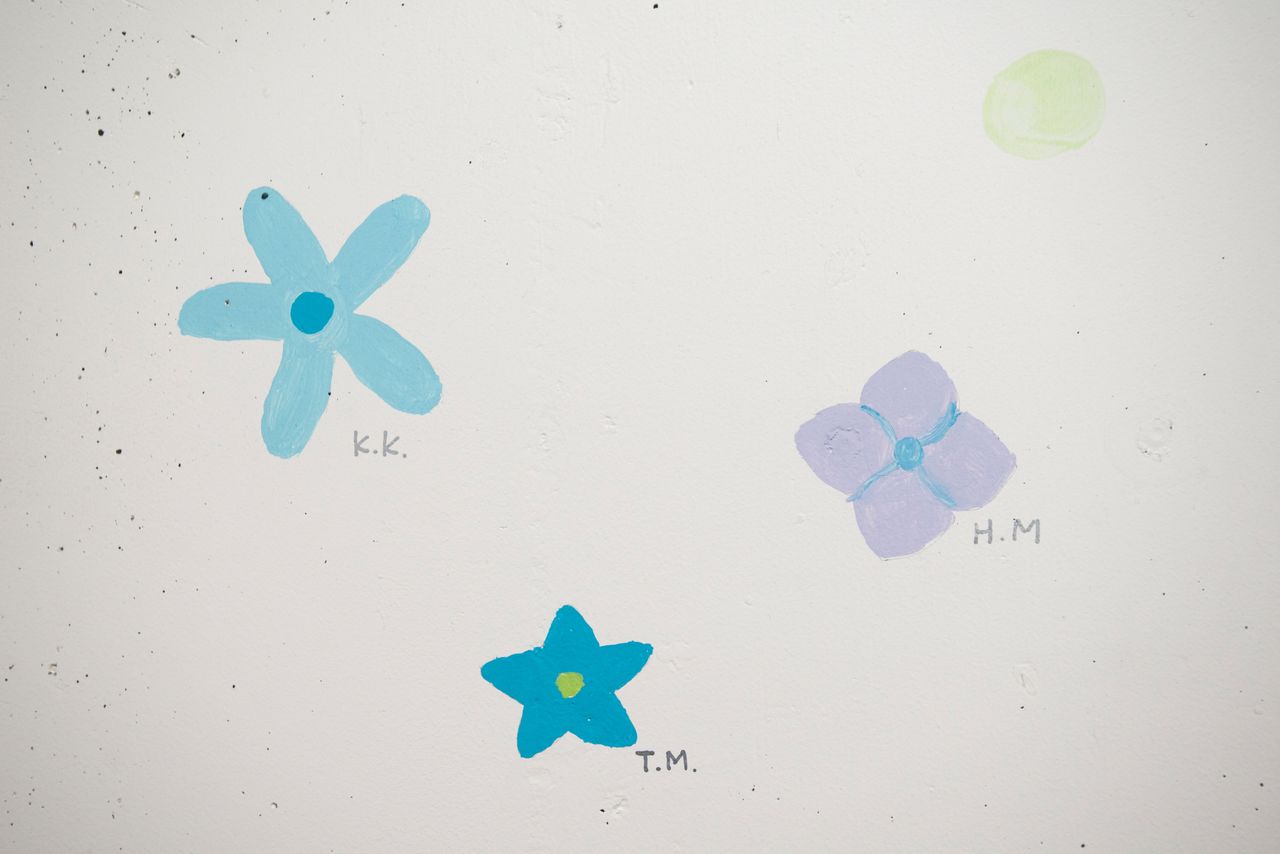

The nursing director felt that the concrete walls were bleak and lonely. Mori discussed the issue with creators and came up with the idea of a floral tribute design that included blue flowers painted by 177 employees.

A mural painted by employees along the underground corridor pays tribute to the deceased. (Collaborating artist: Shimada Reiko.) (© Kodera Kei)

Some of the staff cried as they helped to paint the mural. After it was completed, some nurses were moved to tears when relatives of the deceased expressed their appreciation as they passed through the corridor. Through the experience, Mori realized that it was not only patients and their families who needed consoling, but also the hospital staff, who empathize with those who are suffering.

“This hospital is a participatory environment that everybody creates together,” says Mori. “I think that by expressing the sincerity of the medical staff, the patients, and their families, they are being cared for in ways that are not obvious.”

Staff included their initials with the flowers they painted. (© Kodera Kei)

Alleviating Pain Outside the Hospital

Mori is developing art to alleviate pain not only inside the hospital, but also outside of the facility. The first step has been to offer grief support for families who have lost children.

She is working together with child-death review researchers, people who have lost close relatives, and hospital staff to produce “grief care cards” carrying messages for bereaved family members. They are also developing a smartphone app that shows users images of art and natural scenery.

The Medical Center endeavors to tackle a broad range of suffering. Mori intends to continue her efforts to understand the pain of others, engaging in dialog with a range of parties to light a path of hope, whereby, through art, people can find hope for themselves.

Mori stands in front of the giant camphor tree artwork created to use in the app. (© Kodera Kei)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Mori with researchers involved in the development of a smartphone app and grief cards. © Kodera Kei.)