Addressing Social Issues Where Art and Welfare Meet

Exploring Art’s Potential for Social Reform with Artist Hibino Katsuhiko

People Society Culture Art- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Breaking Down Established Concepts to Find New Fields of Expression

“About forty years ago, I visited an art museum in Lausanne, Switzerland, that specialized in art brut works by disabled people and others who had no formal art training. The works had a deep impact on me.”

So says Hibino Katsuhiko, president of Tokyo University of the Arts (known as Tokyo Geidai) and an internationally active artist. He has produced works with corrugated cardboard, generally considered a packaging material, along with advertising design and stage art. His self-expression transcends genres. Hibino has also visited welfare facilities and depopulating villages, proactively collaborating with local communities in artistic expression. Throughout his career, he has produced a succession of art projects that are the antithesis of the prestige typically associated with Tokyo Geidai. According to Hibino, the starting point for him was his encounter with art brut.

“After you learn how to use scissors, you can’t return to the time you were unable to cut,” he explains. “In the same manner, once a concept becomes established, it’s hard to break free of it. But by smashing existing values and the techniques that have been instilled in us, we can pioneer new fields of expression—this was the kind of potential I sensed in art brut.”

Hibino currently directs Tokyo Geidai’s Diversity on the Arts Project (DOOR). This certificate program features expert guest lecturers in diverse fields, such as people with disabilities, those supporting initiatives to address child poverty, and LGBTQ+ people, as part of the process of recapturing modern welfare in a broader context. Course participants include 50 Tokyo Geidai students and 125 members of the general public who work together in an effort to find ways to resolve social issues through the power of art.

Participants in the program from the latter category, this author included, have been stimulated by its initiatives for approaching social issues with new concepts.

Art that Opens Doors in Society

Hibino explains the genesis of the concept of blending art and social welfare. “Since my encounter with art brut, I was intrigued by its expressiveness that was not bound by common sense or other values. I received an invitation from Japanese art museums that hold and exhibit art works by disabled people to visit welfare facilities to try and produce art over a number of days. This came about as a result of my being asked to direct the TURN art project, launched by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government as one of its cultural initiatives. The project’s mission was to harness the special characteristics of art that discovered value in difference, while helping diverse people to produce some form of expression in order to contribute to the creation of a society accepting of diversity.”

For Hibino, who had not had a great deal of contact with people with disabilities, it seemed as if he would be “traveling to the farthest ends of the earth.” But while he was living with them and producing art, Hibino says he was moved by how directly they expressed their genuine wishes: saying “I want to draw this right now,” rather than contrived ideas such as wanting to draw something better than the day before. “Such a state of mind is totally unattainable for people who have been trained to believe they must improve each day.”

In August 2014, Hibino stayed at a welfare facility in Hiroshima Prefecture for a week helping residents to create works of art. (© Miwa Noriaki)

Based on his experience, he wanted Tokyo Geidai students to visit such facilities to gain similar stimulation, and to help facility residents to become more open toward artists. Thus, as dean of the school’s Faculty of Fine Arts, seven years ago, he launched the new DOOR course. Jurisdiction for the course was transferred to the university head office in 2024, and the university plans to open admission to members of other organizations, such as government offices and nursing schools.

The program name, DOOR, encompasses the opening of new doors. Building on the Japanese term tobira, meaning door, Hibino also proposed the Tobira Project, a collaboration between Tokyo Geidai and the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum (often called “Tobi”), to foster community through art, using the museum as its base. It was also Hibino who devised the term tobirā, something like “tobirers,” to describe the art communicators involved in the project.

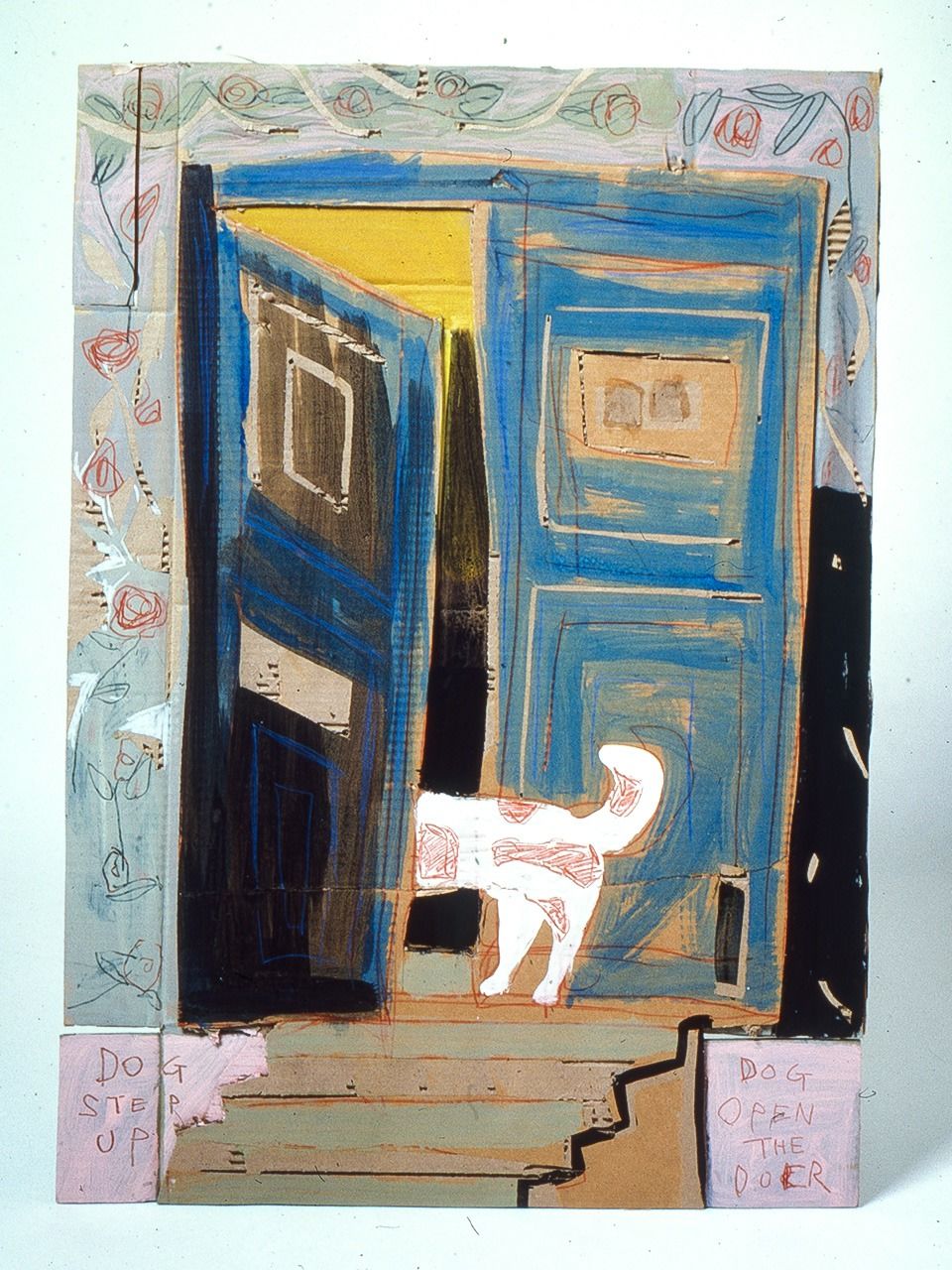

Personally, I associated DOOR with one of Hibino’s early works, Dog of the Door, which depicts a dog sticking its head through a door. The world that the dog sees beyond the door is different from the world that we see from our perspective. Due to the discrepancy in perspective, the dog can see a different scene: it can see what is beyond the door, which is not shown in the picture. When this work is re-examined with this perception, it seems close to the concept behind DOOR: to “shine light on art to make the invisible visible.”

Hibino’s piece Dog of the Door (1983, acrylic on corrugated cardboard, from the artist’s collection). (Courtesy of Hibino Special)

Ideas Rather than Things

The DOOR program is a practical course exploring the nexus of art and welfare. In addition to the compulsory subjects, it offers electives such as fieldwork in care workplaces, art museums, and regional areas, whereby students come into contact with real sites and people. Examples include visiting an orphanage to create and exhibit art that communicates its work to wider society, and a stay in a rural satoyama community to produce art that reflects the sensory experience. Each of the programs emphasizes the creative process and expression that sparks ideas, rather than the objects created.

The Japan Football Association collaborated with DOOR in planning and proposing a way for hypersensitive children and their families to feel at ease attending football matches. The result was this “sensory room,” which was installed at the National Stadium for the Emperor’s Cup final. (Courtesy of Tokyo University of the Arts DOOR)

Hibino describes the time he viewed artworks with Shiratori Kenji, an art critic who is totally blind, at the Contemporary Art Museum, Kumamoto, where Hibino is director. “Because you and I can see a painting, we consider it a work of art, but Shiratori, who cannot see anything, perceives a group of people standing in front of a painting discussing it as a ‘happening’ of sorts, and he appreciates the entire art space. Through discussion with him, I learned that pictures are no more than a means—the work of an artist is to create that something that generates some kind of response in the viewer.

Like Art, Yet Unlike Art

Even though he is working as president of Tokyo Geidai, Hibino does not pursue just high-level specialized education—rather, he prefers to place both himself and his students into environments that produce art brut. This also corresponds with the ideas of Keith Haring, the darling of the pop art world, whom Hibino became close to in the 1980s while he was based in New York.

Haring, who was the same age as Hibino, died of AIDS-related complications at the age of 31. He is well-known for having convened workshops for children around the world, creating artworks for orphanages, and so on, with the aim of eliminating social prejudice and discrimination.

Hibino has also staged events in various locations with the aim of using art as a starting point for social change, including Hibino Hospital, a workshop series based on a concept of therapy through art, and the Day After Tomorrow Morning Glory project. As he explains:

“As part of the Day After Tomorrow Morning Glory project, which I began in 2003 with residents in the Azamihira district in Tōkamachi, Niigata Prefecture, we raise flowers and collect their seeds. These seeds are packed with genetic information of the ‘feelings’ that budded at that time. They are passed on to students in the following year’s DOOR program and participants at the locations of subsequent art projects. With this project, I sought to produce art that is like art, yet unlike art. It’s an attempt at expanding new possibilities for art, by creating a tomorrow that is not like tomorrow but rather the day after.”

The building of a closed school that was used to stage the Day After Tomorrow Morning Glory project. Many DOOR students are taking part in the project. (Courtesy of Hibino Special)

Fostering Talent to Open the Next Doors

As Japan’s only national comprehensive art university, Tokyo Geidai has spawned many artists in the roughly 140 years since its founding. But Hibino is apprehensive. “By merely nurturing a handful of artists, Geidai risks becoming something like a natural monument, frozen at a single moment in history.”

He fleshes out his concerns. “Artists look at a range of minorities, and are stimulated by diverse communities. It is by freeing their imaginative powers, unbound by established concepts and fixed ideas, that they are able to fully exercise their abilities. In that way, expanding the breadth and potential of artistic expression can also be linked to welfare. I hope that Geidai can strive to create a platform in contemporary society where anybody can feel the life force art possesses—a thing that transcends human knowledge.”

Looking forward to the next 140 years, this artist who has already opened many doors hopes to foster artists who will open the next ones.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo © Kawamoto Seiya.)