Confronting the Years: A Photographer’s Tour of Japan’s Hyper-Aging Society

Forward-Thinking Hokkaidō Initiative Meeting Eldercare Needs with Global Talent

Society Health- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Caregiving in a Foreign Country

Foreign workers are now essential in many industries across Japan. Their numbers, according to the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, reached 2.3 million in October 2024, a 12.4% increase over the previous year, with the highest growth, at 28.1%, being seen in the healthcare and welfare sector.

Caregiving for the elderly is a particularly demanding task, both physically and emotionally, requiring strong communication skills and a good understanding of the Japanese language.

To learn about the experiences of foreign workers in such settings, I visited Nukumori no Ie En, a government-subsidized nursing home for the elderly in the town of Takasu in central Hokkaidō that has been employing locally trained foreign care workers since 2021.

Nukumori no Ie En is operated by a social welfare corporation called Satsuki-kai, which currently has six foreign staff members. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

“Are we ready? The first letter is ko,” announces Tamang Sanu, 25, in a clear and cheerful voice, as she leads residents of the nursing home in a traditional card game of karuta. A native of Nepal, she communicates with the participants in fluent Japanese.

“Look, look, it’s right in front of you!” pitches in Sam Satyarith, 30, from Cambodia. They both seem to be enjoying engaging with the residents.

Tamang claps as Sam, standing, helps players locate cards in a game of karuta. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Tamang developed an interest in Japan as a teenager after befriending a Japanese woman. She studied management at university but chose to come to Japan five years ago to pursue career opportunities here, acquiring certification as a care worker three years ago. “Population aging isn’t a big problem back home right now, but I wanted to come to Japan to learn the skills to deal with such an eventually,” she says. “The things I learned in nursing classes, such as when to intervene and the tone of voice I should use, have been very useful.”

How do the residents feel about their foreign caregivers? “They do a wonderful job,” comments 93-year-old Miyamoto Teruko. “They’re really kind and speak Japanese well.”

“They work very hard, even though they’re far from home,” notes Miyamoto Teruko. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Sam came to Japan eight years ago and is now in his fourth year at the facility. “I enjoy talking with older people,” he says. “I became interested in pursuing nursing as a profession because my father works in Japan as a doctor. I came to Higashikawa because I was able to receive a scholarship to study, and also because Hokkaidō is so beautiful.”

Sam recounts the reasons for choosing to work in Hokkaidō. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Training in Eldercare and Social Welfare

Both Tamang and Sam studied at Asahikawa Welfare Professional Training College, since renamed Higashikawa Training College of International Culture and Welfare, in the town of Higashikawa, Hokkaidō. Of the 91 students currently enrolled in the school’s department of nursing care and social welfare, which offers a two-year course in caregiving, more than half, or 49 students, are from outside Japan—mainly Asian countries like Indonesia, Vietnam, China, Thailand, and Malaysia.

A class on providing bathing assistance. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Classes provide students with hands-on training in caregiving techniques, such as minimizing physical strain on those being cared for. “When you’re showering someone,” points out veteran instructor Itō Yoshiaki in the training room, “start from the periphery and move to the center. It’s less stressful on the body if you start far from the heart. When residents are in the bathtub, they’re relaxed,” he adds, “and that’s the best time to connect with them through conversation and gentle massages.”

As trainees lend a hand in helping bathe a fellow student in the role of a resident, a relaxed, congenial mood permeates the room.

Itō Yoshiaki, standing at the head of the bath, instructs students on bathing techniques. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Students practice helping people move from their wheelchairs. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

A Long-Term Investment

Higashikawa is well-known among photographers for its unique 1985 declaration proclaiming itself a “town of photography.” It seeks to harness the power of photography to preserve its beautiful natural environment and create a community that is open to the world.

It also garnered attention as a rare town whose population has been growing as most other municipalities in the country have been shrinking. Over the past three decades, Higashikawa’s population has increased 20% to 8,600, thanks in part to its welcoming stance toward foreigners. Under the leadership of Matsuoka Ichirō, who was mayor from 2003 to 2023, the town launched a short-term Japanese language and cultural training program in 2009, and in 2015 became the country’s first municipality to establish a public Japanese language school to encourage global talent to relocate.

Anticipating a future shortage of caregivers, the town in 2018 established a council to support foreign care worker development in collaboration with nearly 30 municipalities in northern Hokkaidō and local social welfare facilities. Asahikawa Welfare Professional Training College was positioned under the project as the institution to train such care workers.

The Asahikawa Welfare Professional Training College’s main building, with its iconic white tower. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

The council offers scholarships to international students who commit to working in member facilities for at least five years after graduation. The two-year scholarship covers ¥5 million in tuition and dormitory fees, along with an allowance based on the student’s Japanese language proficiency. Students who leave the program midway must repay the scholarship to the council.

Japan as a Leader in Eldercare

Despite this innovative system, some students do leave before completing the five-year commitment. “That’s why it’s important to achieve a proper match between students and facilities,” points out Hirato Shigeru, executive director of Asahikawa Welfare Professional Training College. “We arrange tours of all member facilities for first-year students to ensure compatibility. When an agreement is reached, facilities cover the scholarships of the students they wish to hire.”

The nursing home where Tamang and Sam work expressed a desire to hire them while they were still undergoing training, and both reciprocated the offer by conveying their interest in working there. As a result, the transition to the workplace has been very smooth, with both Tamang and Sam saying they are satisfied with their jobs.

Hirato Shigeru played an instrumental role in establishing the council to train foreign care workers. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

“We ask that all students fulfill their five-year commitment, but we really want them to stay in the community much longer,” Hirato notes. “Some will choose to return home, though, to work in eldercare, and I understand that. Japan is a leader in this field, so having Japanese caregiving qualifications can be a valuable asset. We’re sad when people go, but we wish them the best.”

Life in Higashikawa

I visited the Higashikawa training college to observe the life of international students there. One of them was Kim Sehyeon, a 36-year-old from South Korea who came to Japan in April 2024 to enroll in the school. He says he developed an interest in nursing care after working at various jobs in his home country.

He speaks fluent Japanese, having studied it as an elective in middle and high school. “The population of South Korea is rapidly aging,” Kim says, “but there are very few residential facilities—mostly daycare and home-visit services. So, many households wind up hiring live-in housekeepers to look after older family members.”

Kim describes life in Higashikawa as comfortable and stress-free. He has a private room in the school dormitory and is provided with two meals a day, except when the dormitory kitchen is closed on Sundays and holidays. Each month, students also receive ¥8,000 worth of HUC points, the local electronic currency, that can be used at select shops in Higashikawa. Kim looks forward to working in a council-affiliated facility after graduation, saying he is already familiar with caregiving terminology.

Kim makes a purchase with a Higashikawa Universal Card. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Kim video chats with his mother. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Students write their names using brush and ink during kakizome, the first calligraphy of the New Year. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Students display their finished works. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Students from Southeast Asia enjoy the outdoors of Higashikawa. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Students caring for the elderly ponies that belong to the school’s department of nursing care and social welfare. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

A Model of Multicultural Coexistence

The training college also has a department of Japanese language for students hoping to improve their language skills before joining the workforce. Along with the municipal Japanese language school in Higashikawa, the department contributes to enhancing the Japanese language proficiency of foreign workers.

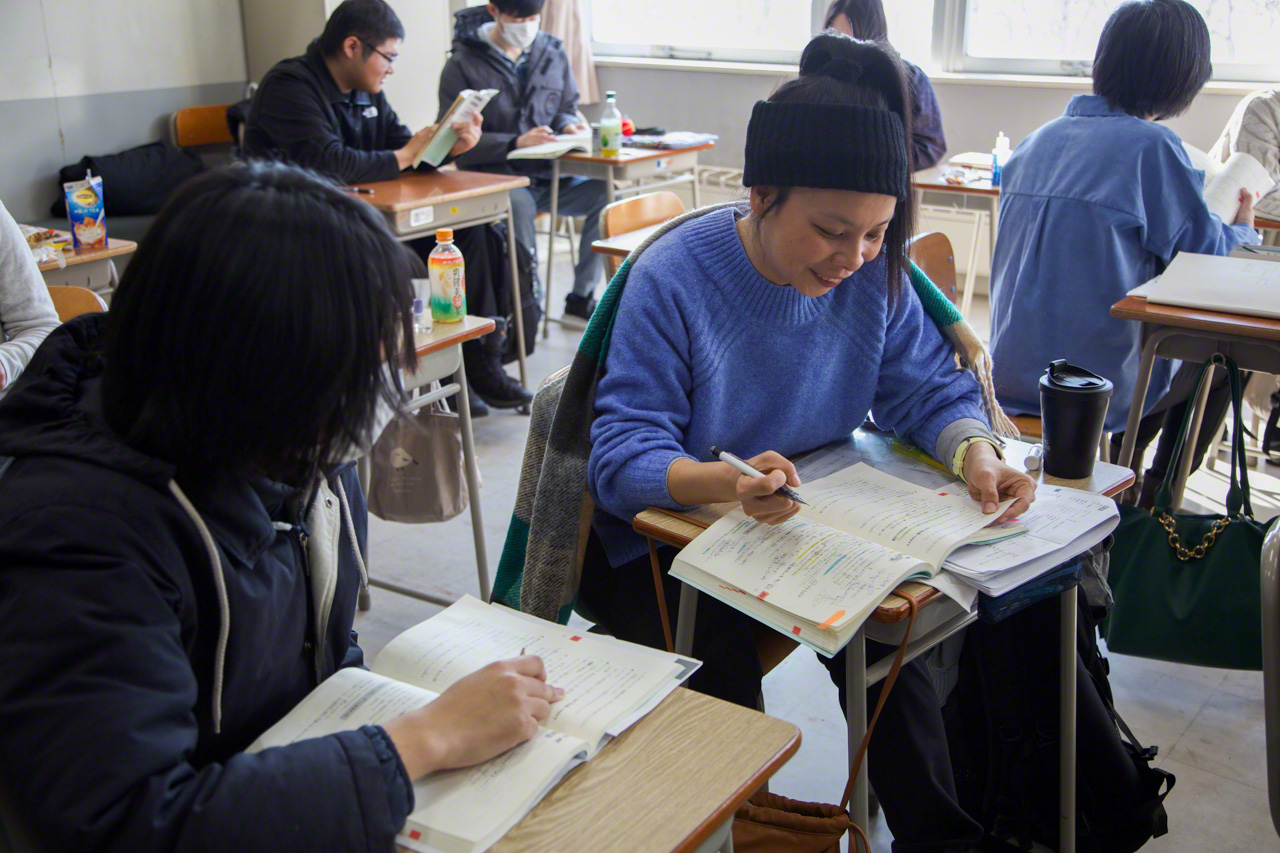

A Japanese language class at the training college. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Higashikawa’s municipal Japanese language school, meanwhile, has what it calls a “multicultural coexistence room” to promote exchange between foreign students and local residents. The words posted at the room’s entrance read: “All of Higashikawa’s foreign residents, visitors, and townspeople are one family.”

I thought this was a very apt expression of the spirit of multicultural coexistence that did not rely on overworked buzzwords like “global,” “universal,” or “diversity.” In it, I sensed a deeply rooted inclusiveness that might be termed the “Higashikawa spirit.”

It also reminded me of the local spring water that wells up, pure and abundant, several decades after falling as snow on the nearby Daisetsu Mountains. Higashikawa is the only township in Hokkaidō without a waterworks system, since spring water is readily available at the turn of the tap. One might even say that the pristine and rich quality of the town’s water is the very wellspring of the “Higashikawa spirit.”

I hope to return to Higashikawa in around 10 years’ time to see how this remarkable initiative to develop foreign caregivers will have evolved.

Behind the white tower of the Asahikawa Welfare Professional Training College lie Mount Asahi, right, and other peaks in the Daisetsu Mountains. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

(Originally published in Japanese. Photos and text by Ōnishi Naruaki. Banner photo: Tamang Sanu, a care worker from Nepal, provides meal assistance at a nursing home in Hokkaidō. © Ōnishi Naruaki.)