Confronting the Years: A Photographer’s Tour of Japan’s Hyper-Aging Society

Grocery Store on Wheels: A Lifeline for Shopping-Challenged Seniors in Japan

Society Health- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Checking In with Cheerful Chatter

The town of Hino is a rural, inland community in southwestern Tottori—Japan’s least populated prefecture. It lies in the Hino River basin, whose iron sand was used in the past to produce steel in tatara furnaces. Today, it is at the forefront of population aging; the share of the population aged 65 or older exceeded 50% in 2019, putting Hino in the category of a “marginal village” that is at risk of disappearing due to depopulation.

The headwaters of the Hino River are in Okuizumo—a land steeped in myth and legend. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Helping meet the food needs of many of the community’s elder residents is Takada Akinori, a farmer-cum-shop-owner who operates a mobile grocery service to deliver not only food but also good cheer.

“Did you know shijimi clams taste better if you freeze them once?” Takada says with a smile as he hands a bag of groceries to an elderly resident.

“That’s a mighty handy tip. I’ll give it a try!”

“That’ll be 1,489 yen,” he adds. “My, looks like you’ve saved up a lot of coins . . . that’s quite a fortune there!”

Takada took up farming in Hino in 2010 when he was 27, learning the basics from seasoned locals keen on passing on their knowledge to the younger generation. He started by growing rice with rented farmland and equipment.

At the time, the town had 3,900 residents, but the population has since dwindled to under 2,600. Over the years, many elderly farmers who could no longer look after their fields entrusted the task to Takada, and today, he manages 10 hectares of farmland in seven separate hamlets, making him the largest farmer in town.

Takada harvesting spring onions from his neatly tended field (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Doing What No One Else Was Willing to Do

Takada’s life took an unexpected turn in 2022, when Aikyō, the only in the neighborhood located just outside Kurosaka Station on the Japan Railways Hakubi Line, announced it was shutting its doors after 30 years. As town authorities began searching for a successor, the shop owner privately approached Takada—who by this time had become a pillar of the local community—asking him to take over the business.

The owner felt Takada would be perfect, as he was popular and well-regarded by his neighbors. He was sociable and outgoing by nature, regularly inviting people of all ages to his home and serving plates of sashimi that he ordered from the shop.

Initially, Takada turned the offer down. “Losing Aikyō would be a big blow, for sure, but I’m a farmer and can’t run a supermarket,” he argued. “Plus, this would force my wife to change her lifestyle.” His wife, Miki, had been working as a school nurse while raising their three children.

He realized, though, what the store meant for a community facing depopulation, especially for the elderly residents he knew well. “There aren’t too many pedestrians around the station, but still, we can’t let the lights go out,” he thought. “And if no one else is willing, then I guess I’ll have to do it.” He made it a condition that for him to take over, the local government would have to help.

Takada established a company to run Aikyō, including—with municipal support—its mobile grocery service, and got the town council to approve an elderly watch program to check on older residents during his sales rounds. Half from prodding by others and half from a personal sense of mission, he and his wife, who quit her school nursing job, have been meeting the market needs of the community over the past two years,

There is usually little traffic along the street in front of Takada’s shop. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Fresh Fish Popular with Mobile Shop Customers

Takada with his wife and kids. Miki oversees both in-store and mobile operations. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Mornings are a very busy time for the supermarket, with Miki packing fresh produce and attaching price tags. Her husband drops in everyday, but the shop is basically run by Miki and a dozen or so employees.

The store manager is Miseki Noboru, who is also in charge of the fresh fish section. Having worked at a local co-op before joining Aikyō under its previous owner, he is a 40-year veteran of mobile grocery sales. Miseki leaves at six in the morning to the Sakaiminato market, located along the Sea of Japan coast about an hour’s drive from Hino, so the fish is always fresh—quite a rarity considering the shop’s inland location.

Takada has great trust in Miseki, saying, “He’s the reason we were able to keep the store going.” (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Takada thinks about the preferences of the customers he will be visiting that day in choosing the products to load in the grocery truck. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Shiitake is a Hino specialty, and Takada’s truck is decorated with an illustration of a smiling mushroom mascot. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

“It Helps Keep Me Alive”

The mobile grocery truck visits different neighborhoods depending on the day of the week. Most customers are elderly residents who have either relinquished their driver’s license due to age, have lost spouses who used to drive, or need family assistance and can only go shopping on weekends.

The arrival of the truck to each home along the route is signaled by loudspeakers playing a 2003 song about the famous sand dunes along the Tottori coast. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

A 90-year-old woman is happy with her purchases, saying, “I’m going to have simmered squid tonight.” (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Takada tells a man who loves sashimi that he is in luck—today’s catch is top quality—to which the man concurs, “Your fish is always fresh, the best around. There’s something special about the way the sashimi is sliced, and the radish garnish is really crisp.”

A man places pack after pack of sashimi into his basket, saying, “I always look forward to visits by the food truck.” (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Takada helps a woman carry her shopping bag to the front door. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

“I’m looking for a big bottle of vinegar,” a woman asks. “I’ll be sure to bring it next time,” Takada replies, jotting down the customer’s request to make sure people’s needs are met. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

“The delivery service is a true blessing. It helps keep me alive,” one woman said candidly. Takada now heads back to the shop after visiting around 20 homes. The sun has set, and the skies are already pitch black. After unpacking his truck, his day is finally done.

The Future of Mobile Sales

Food carts and itinerant vendors have been around for ages, so mobile retailing is nothing new. I spent my early childhood in the backwoods of Nara, and I fondly—and still vividly—remember being visited regularly by a peddler with a cart overflowing with household supplies and groceries. It was as if a toy shop, hardware store, greengrocer, and fish store had cropped up all at once. All the kids in the neighborhood would gather when the man arrived and enjoy chatting with him.

As the country became more affluent, people flocked to urban shopping centers to satisfy their craving for consumption. With the recent demographic shift to an older, smaller population, however, many outlying cities have lost their vigor. Stores are shutting down, and even co-ops specializing in door-to-door delivery are pulling out of markets.

Takada, too, sees his mobile service as a temporary solution. “Eventually, it’s going to disappear. I’m simply doing what I can during its slow, final stages of life. But small-scale retail is an essential service. Food is a lifeline, and like other forms of infrastructure, the municipal government needs to ensure that such services survive.”

“People who’re comfortable with mobile devices have no trouble doing their shopping online,” Takada points out. “And the day’s not far off when deliveries will be made to people’s homes using drones—launched perhaps from the rooftops of large supermarkets.”

This is a far cry from the vending carts of my childhood, which were still common just 60 years ago. Lost today are the conversations between merchant and customer, the warmth with which goods changed hands, and the physical contact that buying and selling entailed. Life may be more convenient when purchases are just a click away, but are we happier for it?

Looking After Seniors on the Delivery Route

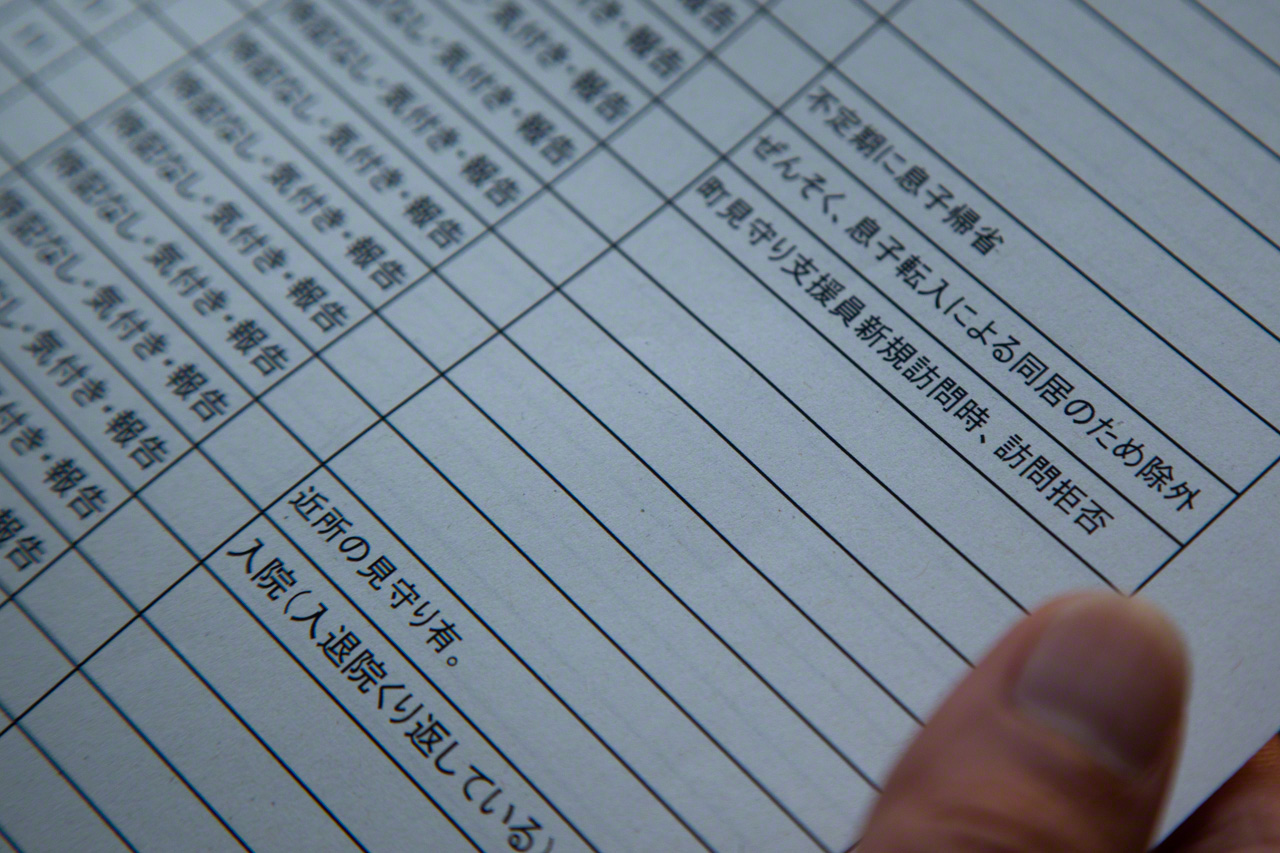

The list of residents under the senior watch program is updated every month. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

In addition to operating the supermarket, Takada is commissioned to monitor the well-being of elderly residents under a program operated in tandem with the town’s health and welfare department and the local social welfare council. He visits around 200 residents each month to check their safety and to provide support when needed.

“It’s nothing very formal,” Takada says unassumingly. “I just drop in and say, ‘Hey, are you still breathing? Any aches and pains?’ And they’ll laugh and say, ‘Yeah, my body’s aching all over!’”

If people on the list are mobile delivery customers, he will check in with them during his route. Or if they are farmers, he will visit them while they are working in the field. And for others, he will go to their homes and report any concerns to town officials. “Shopping behavior can reveal a lot,” Takada notes. “If someone starts having trouble counting change, it could be a sign of dementia. I share this kind of information with the local government.”

The Numatas are old friends who are now both 90. They are not solo dwellers but are subject to senior watch because of their advanced age. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Support from the Town Council

Takada’s value to the Hino community is not lost on the town council, whose chair, Nakahara Nobuo, calls him “irreplaceable.” Recalling the near closure of Aikyō two years ago, Nakahara recognizes that the loss would have been major blow for many people. “Takada’s not a native of Hino, but he offered to look after the rice fields that aging farmers had abandoned, and he also agreed to run our only shop. He’s a vital presence in our community.”

Nakahara, right, looks over a freshly harvested spring onion in Takada’s shed. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

“We certainly need to attract more young people,” Nakahara continues, “but our priority should be to make sure that those who are here will choose to stay. For that we need to provide decent jobs and housing. We’re doing all we can to make Hino a more attractive place to live and work.”

A Smaller Population Means Bigger Opportunities

(© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Takada was born and raised in Fukuoka but attended Tottori University to study environmental conservation (desert greening) and food production. Following graduation, he joined a sake brewery out of his love of sake, working there in the winter, while growing food on a farm from spring to fall.

Why did he choose to stay in Tottori? “My feeling was that the smaller the population, the bigger the opportunities.” If more young people shared Takada’s outlook, depopulation may become less of a problem in Japan.

Kawakita Kōki is currently employed by Takada but hopes to start his own farm in Hino one day. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Originally from Yamaguchi Prefecture, Kawakita Kōki, 30, came to Hino six years ago under the Japanese government’s local. He stayed on after the conclusion of his assignment and is now in his third year in Takada’s employ.

“I’m hoping Kawakita will settle down here with his own farm,” Takada says. “I’ll provide all the help I can with whatever he wants to grow. If he needs equipment, I can buy it and rent it to him, and I can also help him secure good farmland.”

“As long as the municipal office is willing to help,” he continues, “I hope to create jobs here, whether it’s for Kawakita or for the workers at Aikyō. Without employment, younger people aren’t going to stay. And the best way to give back to Hino is to ensure its survival by developing the next generation of workers.”

Takada’s engagement with the community, looking after both the young and old, will continue to unfold in the coming years.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Takada Akinori hands a bag of groceries to a customer of his mobile food service. © Ōnishi Naruaki.)