Confronting the Years: A Photographer’s Tour of Japan’s Hyper-Aging Society

Nozu Kiyofusa and the Art of the Memorial Photograph

Images Society- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Reflections from the Past

In Japan, it is the custom at wakes and funerals to display a photograph of the deceased on the altar. These portraits form a focal point of attention for mourners during the ceremony, and are then often displayed in the family home, where they represent the ongoing connection between the living and the dead. Until recently, these memorial pictures, known as iei, were normally posed studio portraits, in which the person would be shown looking directly into the camera, cropped to show the head and shoulders. Meaning “image/shadow left behind,” the word iei has indelible associations with death, and provokes discomfort in many people, who prefer not to think about the picture that will be on display at their own funeral.

Anyone who grew up like me in the Showa era (1925–89) or earlier will remember the photographs of generations of the family’s deceased that were displayed in almost every home, hanging in frames above the alcove where the butsudan Buddhist altar was kept. I still remember clearly the prickle of unease these pictures used to arouse in me as a child, with their unsettling reminders of uncanny family resemblances across the generations. In those days, the pictures were all black and white—there was never a real sense that the people in the pictures were still vividly present. There was something shadowy, otherworldly about them—the portraits were imbued with a fitting sense of the distance between the world of the living and the dead.

Today, people increasingly hand the funeral company a blurry picture taken on a cell phone and hope for the best. Too often, this leads to ill-advised attempts to enlarge, stretch, and crop the original photo and impose it against a composite blue background. More than once at funerals in recent years, I’ve stepped up to offer incense and felt a jolt as I’ve looked up and noticed the maladroit picture of the deceased on the altar.

From Cosmetics Posters to Memorial Portraits

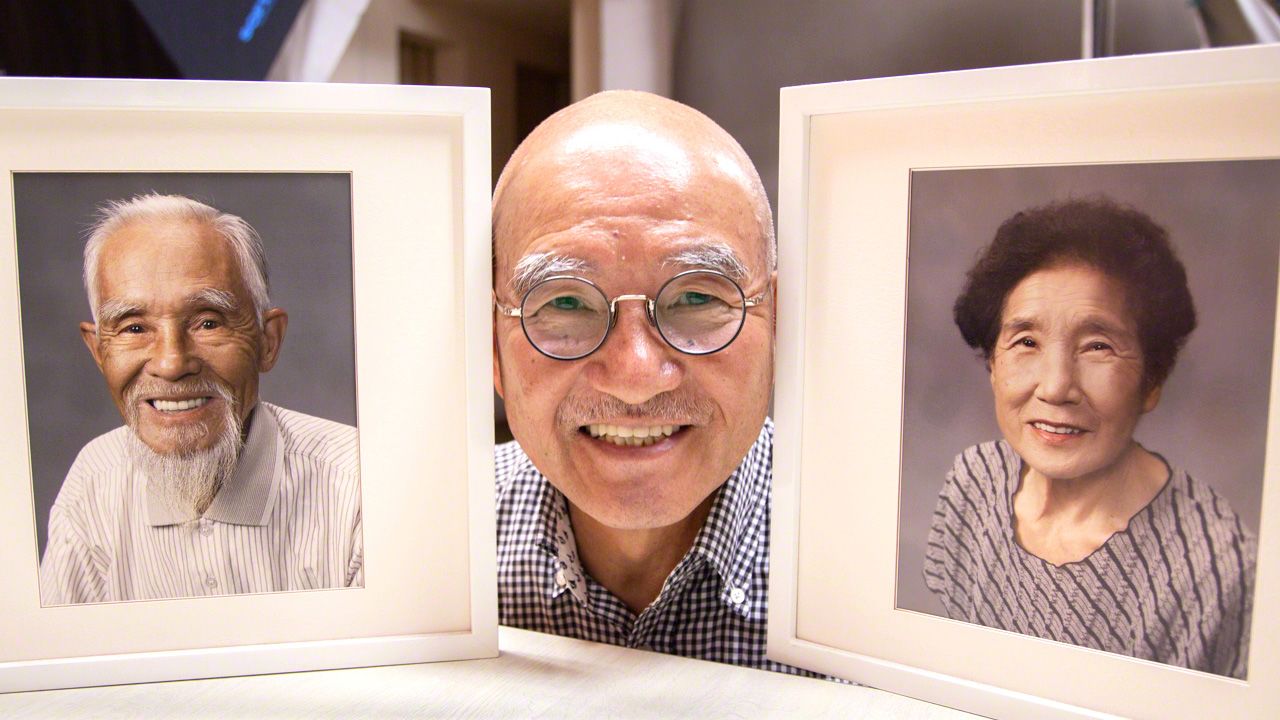

Now 75, Nozu Kiyofusa spent much of his career as a professional photographer specializing in glossy advertising shoots for Shiseidō, Japan’s leading cosmetics company. He still has slightly bitter memories of the circumstances that led to his late-career change of direction.

“When my father-in-law died, there was no photo suitable to use at the funeral. We eventually found a picture that had been taken on a trip somewhere and did our best with that. It was just about good enough for the purposes of the day, but a sense of regret lingered—why had I never taken a proper portrait of him myself, after everything he had done for me over the years? I was determined not to let the same thing happen with my own parents. And I didn’t waste any time. On. my next visit home to see my parents where they live in rural Yamaguchi—that’s when I took these,” Nozu says, proudly displaying the framed pictures used in the banner photo for this article.

“I told them to sit down and let me take a nice portrait of them looking fit and well. They laughed when I told them, ‘I’m going to use this at your funeral when you die.’

“I remember when I looked at the finished print, it was as if I could hear my father’s voice loud and clear. It was as though I was there talking with him. It was quite moving. The power of photography!”

Advertising work can be glamorous, admits Nozu. “Your photo might be blown up to huge proportions and used on posters in train stations, or in the newspapers. But six months later, it’s gone. With a memorial portrait, though, if you take a good picture, it might be cherished for a century or more, by the person’s children, grandchildren, even great-grandchildren. I had an intuitive sense that this was what I wanted to do. If I hadn’t taken that picture of my father, I probably would never have made the switch.”

When he turned 60, Nozu opened Sugaokan, a studio in the Nakano district of Tokyo that specializes exclusively in iei memorial portraits.

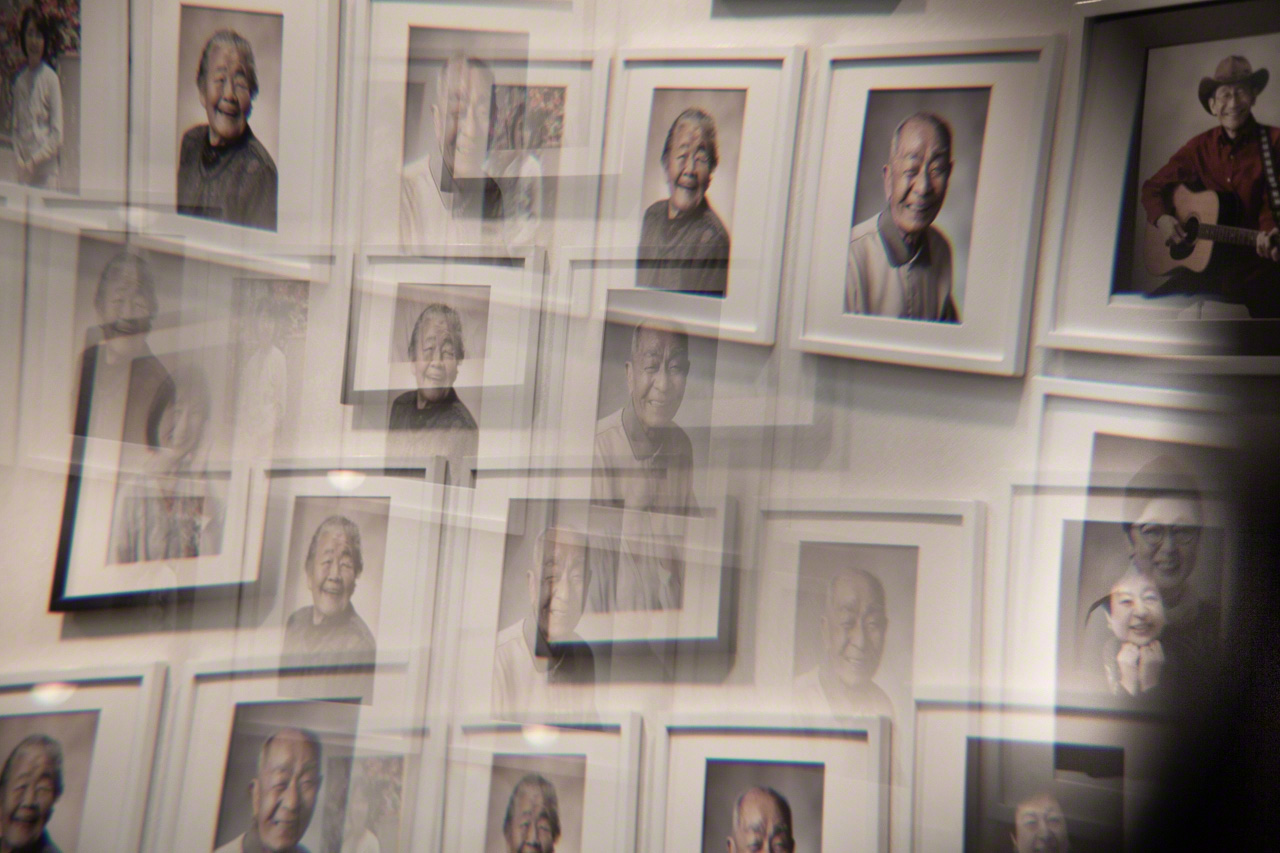

A selection of Nozu’s “special portraits” look out from his studio. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

“I soon realized that any mention of the word iei was enough to put a lot of people on their guard,” notes Nozu. “It’s an inauspicious term associated with funerals and death . . . things people prefer not to think about. I chose the name Sugaokan, meaning ‘the natural’or ‘true face studio,’ because my idea was to take pictures that would capture people’s natural expressions and convey a sense of who they really are. The portraits are just ordinary pictures when I take them—a record of how the person looked on a certain day. It’s only when the person passes away that the photo becomes a memorial portrait.”

The Smiles that Go into Making a Memorial Portrait

I decided I wanted to visit Nozu at his studio and watch him at work capturing his customers for posterity. But first, I needed a model. The first person who came to mind was my friend Yoshida Hiroko.

Yoshida-san has been a friend of my family for 40 years now, ever since our daughters attended the same nursery. Now 80, she remains a fixture in the local community, where she still teaches her beloved tea ceremony and how to wear a kimono.

“I want you to take a memorial photo to be used at your funeral” is not the kind of proposition you can make to just anyone—but I felt sure that my friend would go along with the idea. As expected, she agreed right away, no questions asked.

For her, wearing a kimono is an ordinary, not to say essential, part of everyday life. In fact, she says it’s one of the things that make life worth living. “My daughter laughs at me and says: Knowing you, mom, even after you die you’ll keep fussing with your burial shroud until you get it just right.”

Once hair and makeup are done, it hits home that you’re about to take the portrait that will be displayed at your funeral. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

A photograph is a collaborative effort that relies on close communication between the photographer, model, and makeup artist. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Nozu has been a keen practitioner of aikidō for many years. Absorbed in his work, he seems to subconsciously adapt himself to the ki energy given off by his subject. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Capturing a Moment in Time

Yoshida-san says she only became truly aware of the inevitability of death three years ago, at the memorial service for her sumie (ink wash painting) teacher. When she looked up and saw her teacher’s face, peaceful in death, it suddenly hit her: Your time will come too. “Since then, I keep telling myself: You’re going to have to come to terms with the idea sooner or later, Hiroko.”

Yoshida-san always insists that wearing a kimono changes you and the world around you too. Perhaps photographs have something of the same magical power. The blaze of the flash freezes a moment in time and captures a different truth from the everyday reality we are used to seeing under natural light.

After the session, client and photographer compare several cuts and select the ones they like best. (© Nozu Kiyofusa)

“Looking at the photo, I was pleased that the way I was wearing my kimono made a natural match with my age and body. The photo captures who I am at this moment, with almost frightening honesty. It’s not necessarily a comfortable thing for the person being photographed. A photograph contains so much.”

Yoshida-san has prepared a boxful of things she wants to be put in her coffin, marked “To go with Hiroko.” (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

The Repeat Customers

Saitō Takashi and his wife Kaoruko first visited Sugaokan shortly after the studio opened in 2008. They returned to have a second portrait done in 2013, and they are back for their third visit when I meet them. It is as if updating their memorial portraits helps to remind them how lucky they are to be still alive and sharing their lives together.

Takashi, 82, runs an animal hospital, and plays double bass in a Hawaiian music band in his spare time. Kaoruko is 10 years younger. As well as working at a hospital reception department, she has been a volunteer for many years, doing readings and recordings for visually impaired people.

Kaoruko says she enjoys the makeup option for the way it makes you feel pampered like a princess. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

“In my line of work, I’ve seen many times how quickly life can end. You need to be ready, and preparing your memorial portrait is an important part of that,” says Takashi. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

This time they’ve brought their cat Luna with them. The plan is to take separate portraits, and then a shot of the couple together. The photo session feels almost like a cheerful TV drama episode.

Takashi: I always feel nervous when I’m having my picture taken.

Nozu: You’re too far apart! Move closer!

Takashi: Whoops, guess I didn’t need to say that part out loud.

Nozu: Why don’t you hold hands? A nice, loving pose for the grandchildren. That’s more like it!

Kaoruko, to Takashi: No need to keep sighing!

Takashi: I’m not sighing!

Nozu: Right, now one last shot with Luna. One, two, three, meow!

The pictures at front right were taken 16 years ago, the ones on the left 11 years ago. On the monitor in the back are the latest updates. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

“It’s a bit like going for a health checkup,” Takashi jokes. “You’re stripped naked. It can definitely feel a bit awkward.”

“The first two times I felt embarrassed and kept averting my eyes,” Kaoruko admits. “But this time I was able to look directly into the camera. Maybe I’m becoming less of a scaredy-cat in my old age. I’ll be happy if this picture is the thing people remember me by.”

After the shoot, Nozu sees off his customers, hoping to meet again in a few years’ time. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Close to the entrance to Sugaokan, I notice a figurine of a boy in uniform, a gift from a work connection. “It looks just like me when I was a boy,” he laughs. “Just a coincidence, of course!” Nozu’s cheery disposition and sense of humor surely put his customers at ease and help them relax and be themselves.

Next to the figurine is a piece of calligraphy wishing the business and its visitors “a hundred happinesses.” (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Living with the Dead

In mid-July, I visit the home of Mochizuki Kimiko (84), who lives close to Nozu’s studio. Her husband died six years ago. His memorial portrait was taken at Sugaokan 15 years ago.

For Mrs. Mochizuki, talking to her husband’s photograph has become part of her daily life. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

“When I’m with the portrait I almost feel his presence more than when he was still here,” she says. “I sometimes feel closer to him now than when he was alive—and that’s thanks to this photograph. I start every day by saying good morning to him.”

On this morning, the first day of the midsummer Obon festival of the dead, Nozu visits and puts his hands together in prayer in front of the husband’s memorial portrait.

“His face looks so happy. You can almost hear his cheerful voice.”

“It’s such a good picture of my husband, looking so handsome . . . A photo that captures a person at his best is something precious for the person left behind, and can really help to mitigate the sense of loss,” says Kimiko.

Kimiko had her own portrait taken at the same time. Something in the pictures hints at how close the couple were—and still are. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

While people like Mrs. Mochizuki are happy to share their lives with the memorial portraits of their departed loved ones, Nozu says many people still have a mental block about his line of work. He does his best at professional associations to encourage fellow professionals to take more memorial portraits, and organizes promotional sessions at funeral homes to raise awareness of the importance of getting an appropriate photograph ready in plenty of time.

“The local chōkai neighborhood association gives residents a present when they turn 80. You can either receive ¥5,000 in cash or choose a commemorative gift. I got them to add a photo session at Sugaokan to the list of gifts that people can choose. But so far, only about one person in ten chooses that option, if that,” says Nozu.

“Even so, in recent years there’s been a greater awareness of the need to get ready for the inevitable—something seen in the increasing popularity of the term shūkatsu, or ‘end-of-life’ activities. I think people are definitely more aware of the importance of memorial portraits than they used to be.” I have felt this myself in my own work as a photographer.

Living Links to the Past

Photos on display at Sugaokan: ordinary pictures as long as the person in them is still alive, they become iei or memorial portraits after the person’s death. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

As people age, their faces change. The social face a person has put on for the outside world often tends to fade, to be replaced by the “true” or natural face, shaped and governed by the complex interplay of the person’s genetic inheritance.

In Japanese, the word omokage refers to a shadowy vestige of something that has faded from view: a shimmering form that emerges, slow and indistinct, from beyond the veil of years. I believe that memorial portraits have an important role to play—by helping us to cherish these memories and our ties to the past. They are a valuable reminder of the mysterious, interwoven strands in the tapestry of time and space that have led to our being here in this moment, alive in the fleeting present of the here and now.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Photographer Nozu Kiyofusa with his parents’ memorial portraits. © Ōnishi Naruaki.)