Confronting the Years: A Photographer’s Tour of Japan’s Hyper-Aging Society

New Hope for Hip Pain: My Wife’s Surgery in Photos

Health Images- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Many older Japanese women are at high risk for osteoarthritis (OA) of the hip owing to a common congenital condition. As OA progresses and the pain worsens, it can greatly impact mobility and quality of life. Having suffered from hip pain for decades, my wife finally made the decision to undergo hip replacement surgery. In the following, I document her journey while reporting from the frontlines of orthopedic medicine.

Hip Hooray

The ability of human beings to walk on two legs hinges on our hip joints, which connect the lower and upper halves of our bodies while supporting everything from the pelvis up. The joint’s simple ball-and-socket structure is a wonder of nature, permitting the ball-shaped head of the femur—the longest bone in the human body—to roll about inside the cup-shaped acetabulum for maximum range of motion.

The head of the femur, or thigh bone, fits into and swivels freely inside the cup-shaped acetabulum. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

As the body ages, however, the cartilage that acts as a shock absorber between the ball and socket tends to wear away and break down. The result is hip osteoarthritis, or OA. Older Japanese women tend to be at high risk for OA of the hip owing to a congenital condition called hip dysplasia, in which the acetabulum is abnormally small and shallow. As OA progresses, and the pain worsens, it can severely impact mobility and quality of life.

My wife first began to feel discomfort in her hip when she was still in high school. She adjusted her gait to compensate, resulting in unbalanced muscle development and eventually a discrepancy in leg length. As she grew older, she often found it difficult to walk more than short distances. Whenever the pain flared up, she would give some new treatment a try, and although nothing really helped over the long run, she managed in this way for some 50 years.

Taking the Plunge

I sometimes massaged my wife’s legs and lower back, hoping against hope that somehow her condition would improve. But as the cartilage continued to wear down, the pain became unbearable. At length she elected to undergo total hip replacement surgery, an intervention in which the damaged joint is removed and a prosthesis implanted in its stead.

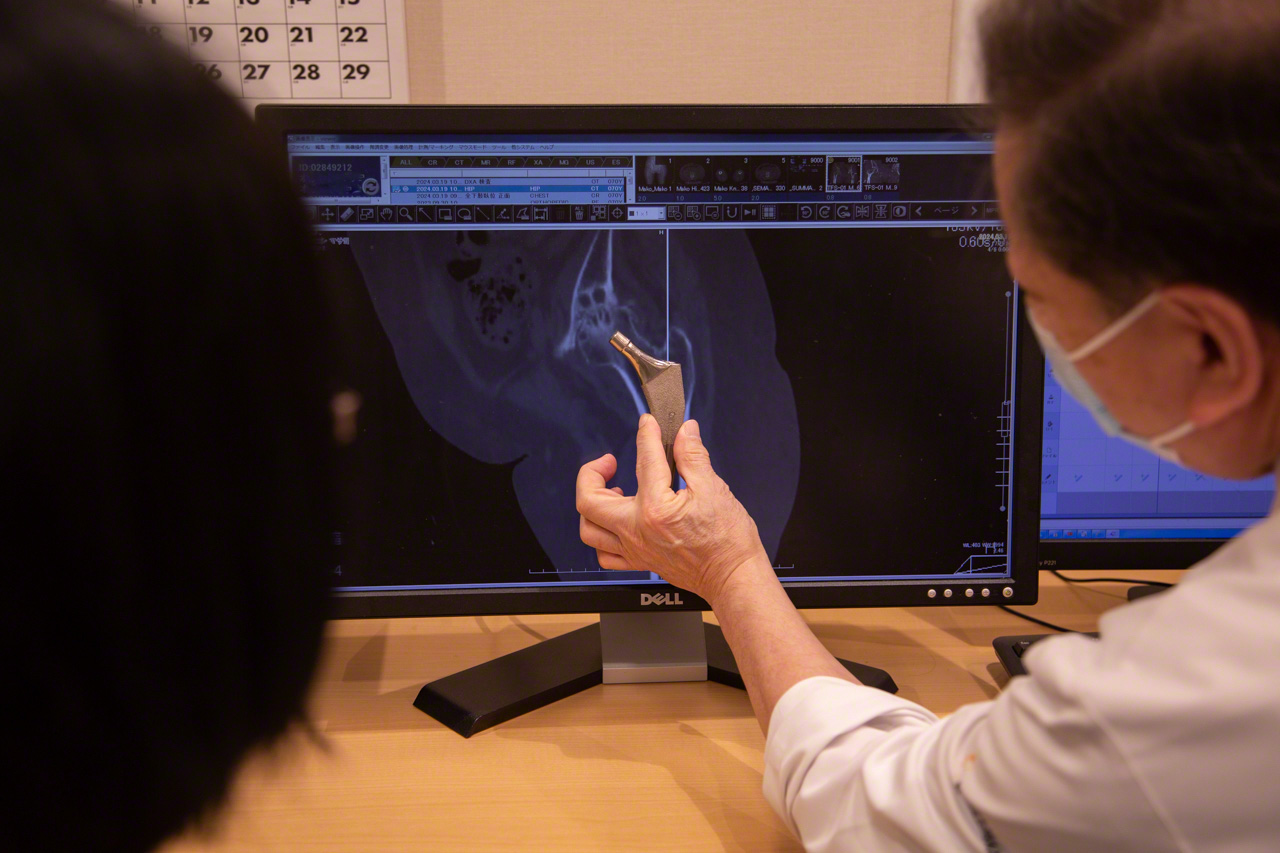

A hip implant system manufactured by the US firm Stryker. The implant weighs about 100 grams more than the bone and cartilage it replaces. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

My wife was already a regular outpatient at Nissan Tamagawa Hospital (Setagaya, Tokyo), a leading center of hip replacement surgery in Japan. The hospital’s Hip Joint Center performs some 1,000 such procedures annually, and my wife was fortunate enough to be assigned the center’s director, Dr. Matsubara Masaaki, one of the country’s top hip replacement surgeons.

In Japan alone, an estimated 4 million people suffer from hip OA, often needlessly. It occurred to me that this might be an opportunity to provide those patients with a first-hand photographic account of the latest advances in orthopedic medicine. With my wife’s consent, I discussed the idea with Dr. Matsubara and the hospital and was able to obtain special permission to photograph and report on my wife’s treatment, from preoperative planning to rehabilitation.

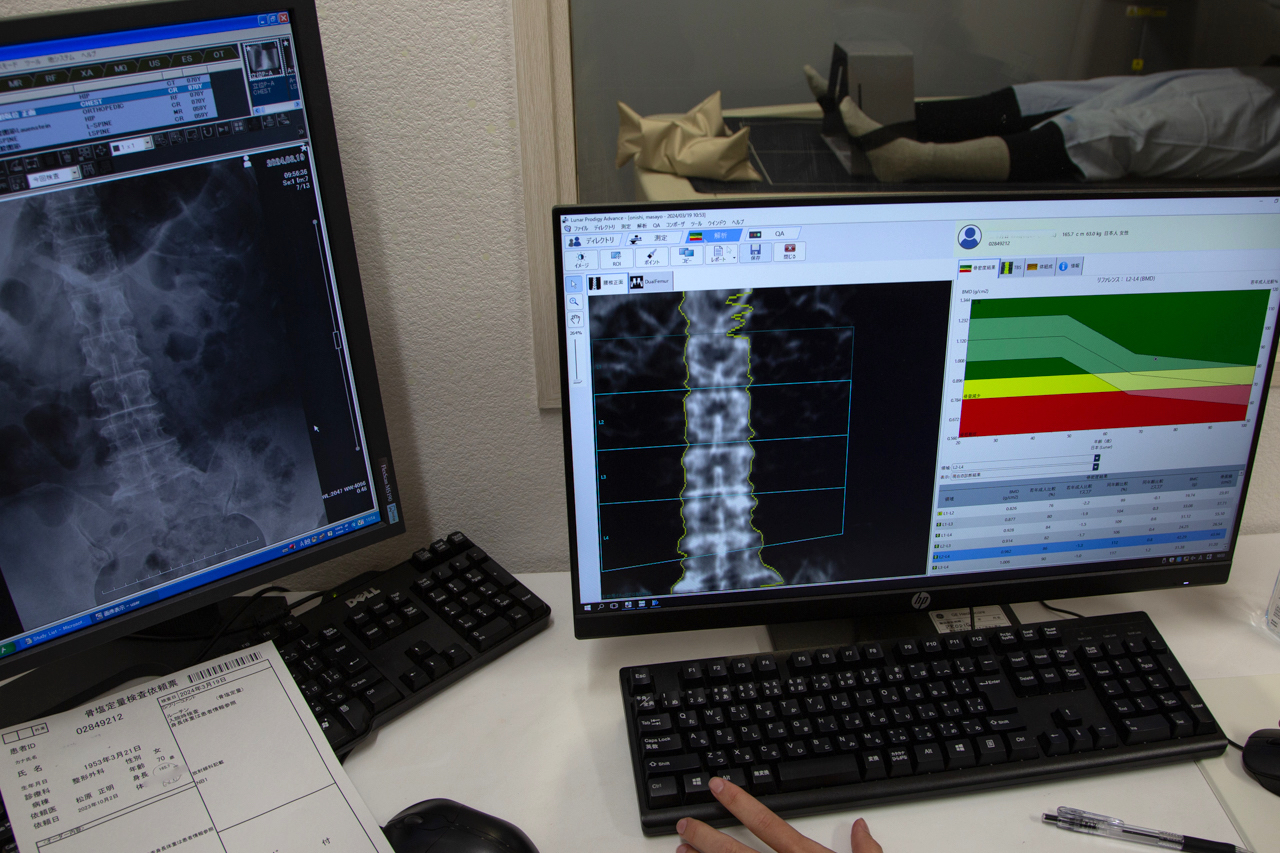

A bone density scan is part of the battery of preoperative tests conducted before hip replacement surgery. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Pre-Op Planning

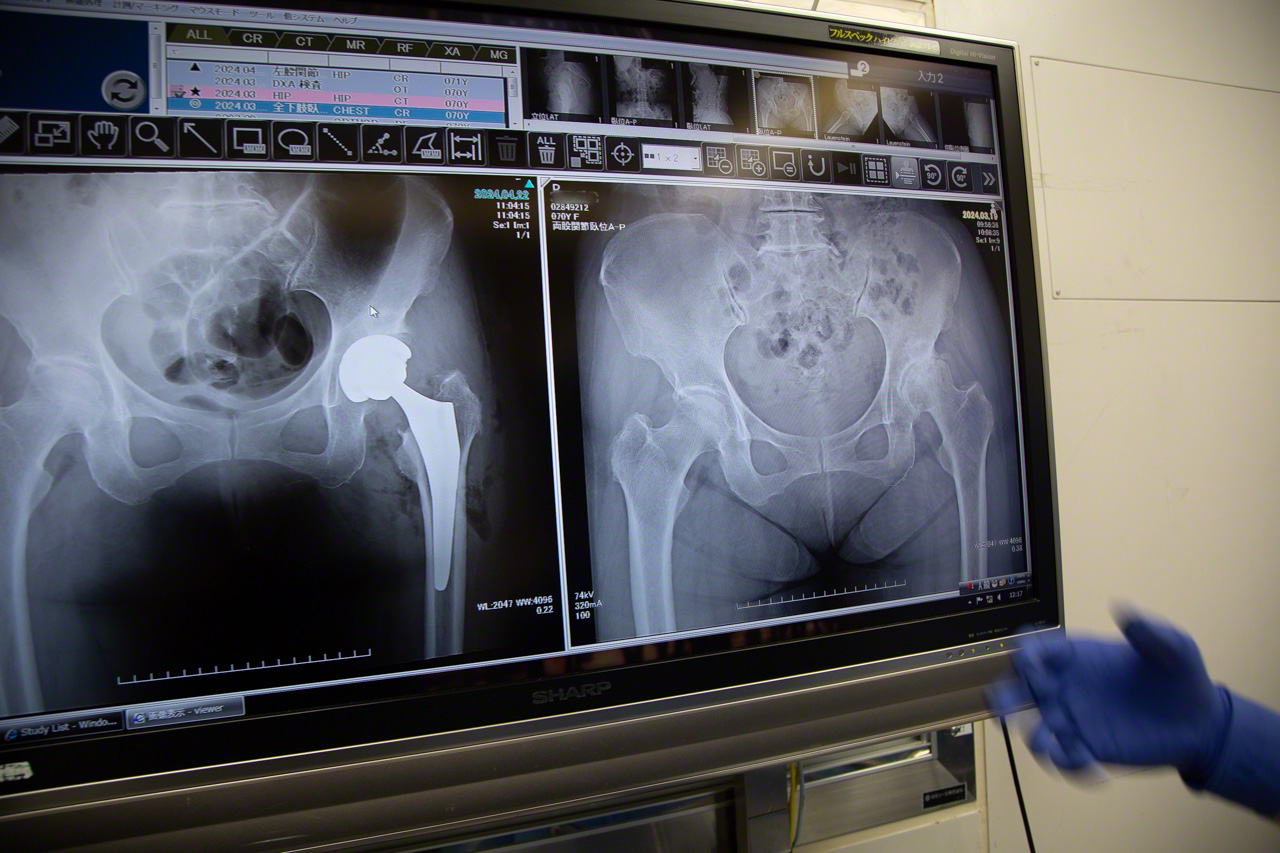

A week before any operation, the patient’s care team gathers in a room referred to as the “drawing studio” to discuss the optimal approach for that patient and draw up a personalized surgical blueprint using dozens of X-rays and other imaging scans.

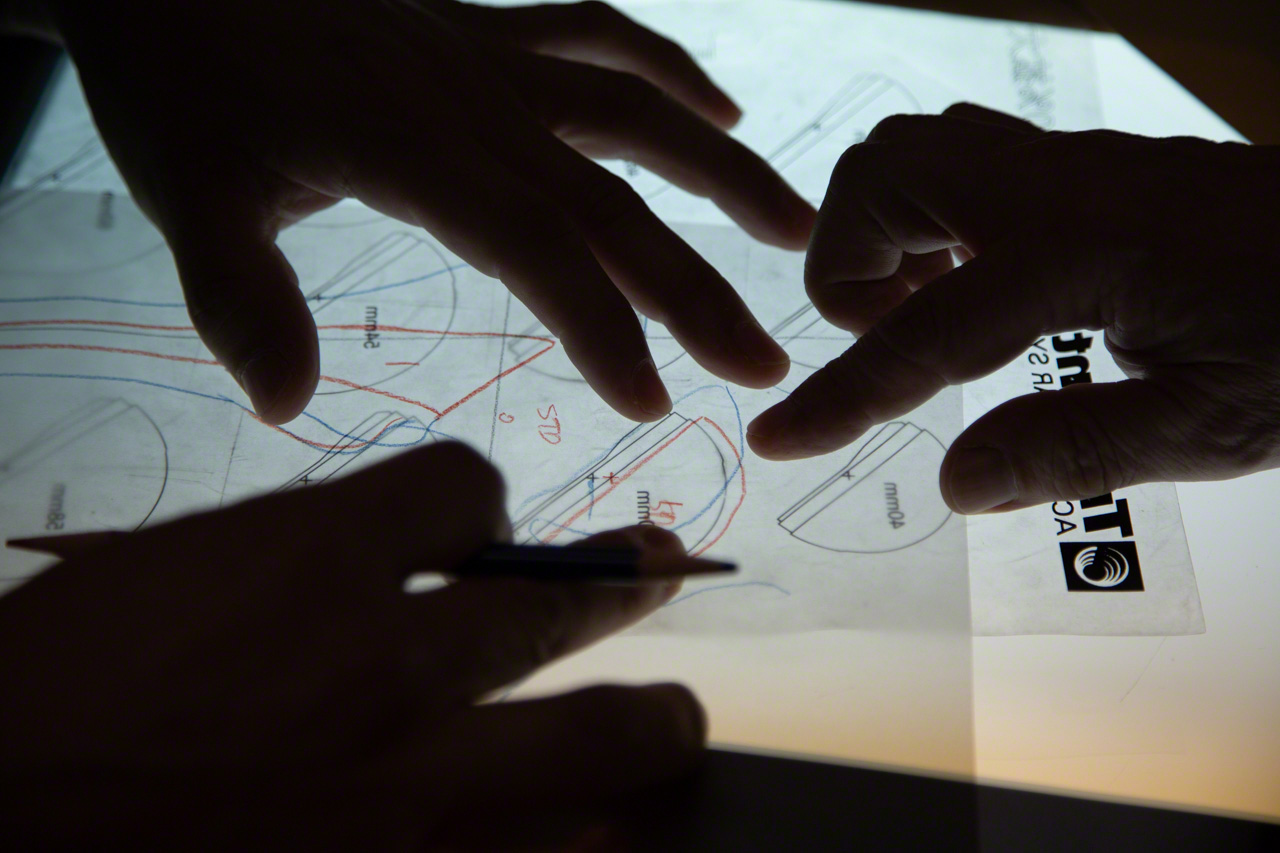

The medical team gathers to draw up a personalized surgical plan on the basis of the patient’s test and imaging results. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Spread out on a desk is a transparency from the device manufacturer printed with different-sized templates of the implant, an acetabular cup. Dr. Matsubara lays a sheet of tracing paper over it and uses one of the templates as a referent while drawing his own diagram indicating the implant’s precise location and angle of insertion of relative to the hip and femur. “I use blue for the bones and red for the implant because I like the way it looks, and also it helps to differentiate,” says Matsubara. “But some people use black pencil for everything. It’s a matter of personal preference.”

Using a protractor and straight-edge, the surgeon draws a precise diagram of the implant in relation to the patient’s anatomy. The exercise helps imprint the surgical plan on the surgeon’s physical memory. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

The two-dimensional drawing seems like an unnecessary step, since the center’s surgical planning and navigation software uses the patient’s imaging data to generate a highly accurate three-dimensional model. But Dr. Matsubara feels that the trial-and-error process of drawing the anatomy and implant with one’s own hand is a valuable preoperative exercise that mobilizes physical memory to imprint the spatial relationships on the surgeon’s mind.

“Of course, we didn’t have 3D software back when I was in training. A senior colleague taught me that drawing by hand helps you see structures and connections that are hidden from view, such as the soft tissues behind the bone. It’s a technique I’ve stuck with for thirty years now,” says Dr. Matsubara.

On the day of each operation, Dr. Matsubara is in the drawing studio from 7:00 AM, hard at work on the patient’s preoperative plan.

“This is how we’ll insert the hip implant,” explains Dr. Matsubara. He spares no time or effort ensuring that each patient understands the procedure and is comfortable with it. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

An extra layer of personal protective equipment, including a surgical helmet, is used to guard against infection, a major concern when implants are used. Matsubara jokes that he became an orthopedic surgeon so that he could dress up in a space suit. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Embracing Cutting-Edge Technology

The surgical team will be accessing my wife’s hip joint from the front, using the anterolateral approach introduced to Japan by Dr. Matsubara himself. Until then, it was standard to access the joint from the back of the body. But that posterior approach involves cutting through muscles and tendons, which can prolong recovery and compromise the joint’s stability. Dr. Matsubara felt there had to be a better way.

At an academic conference, he learned about a new method developed by a German orthopedic surgeon. “I had a gut feeling that this was the answer, so I flew to Germany first thing and got him to teach me the technique directly.” The minimally invasive anterolateral technique permitted the surgeon to operate without damaging muscles or tendons, making for a remarkably rapid recovery. Since 2009, the Hip Joint Center has been using the anterolateral approach for all its hip replacements.

The center has also benefited from Matsubara’s work on prosthetic joints tailored to the Japanese anatomy, navigation systems using 3D CT modeling, and new, user-friendly surgical instruments. Creativity and innovation backed by a wealth of clinical experience are hallmarks of the “Matsubara method,” which is being systematically passed on to the next generation of surgeons at the Hip Joint Center.

The Operation

One of the technological innovations I observed during my wife’s operation was the use of Mako robot-arm assisted surgery. During the delicate process of removing bone to make way for the implant, the surgeon guides a robotic arm, which is programmed to resist the removal of any tissue beyond that indicated in the surgical plan.

The Mako robotic-arm assisted surgery system springs into action. Dr. Matsubara guides the robotic-arm as the attachment spins, removing bone tissue. The monitor at right shows the section to be removed in green. A clean removal leaves only white. Any excess removal appears in red. If the cutting proceeds more than 2 mm beyond the predetermined boundary, the arm automatically stops. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

“The use of this system has fostered a greater sense of security in the operating room,” says Matsubara. “It also facilitates team medicine by allowing any qualified surgeon to operate successfully, instead of relying on the outstanding skills of a few individuals.”

Dr. Matsubara uses a mallet and introducer to seat the artificial acetabular cup in the acetabulum. The surgeon can hear and feel the cup pop into place when the angle and depth of insertion are just right—a more reliable indicator than any electronic gauge. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

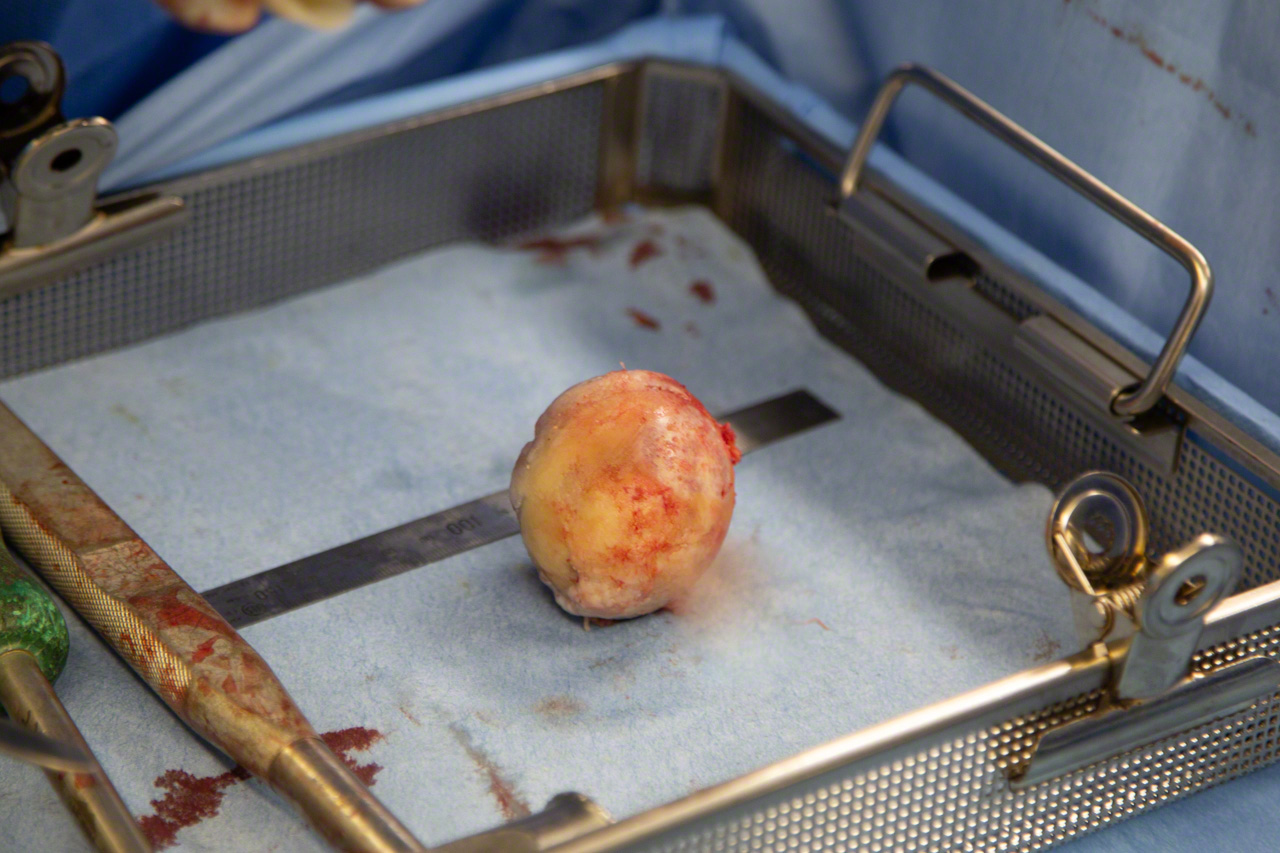

My wife’s surgically removed femoral head. The cartilage, discolored from disease, had worn down to the bone in spots. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Road to Recovery

The surgical team examines a set of X-rays to confirm correct installation of the implant, the final step in a procedure lasting just 1 hour and 17 minutes. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Rehabilitation begins the day after the operation. “What patients need following this surgery is not rest but movement,” says the physical therapist, shown guiding my wife through range-of-motion exercises. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

Before discharge, the patient receives occupational therapy tailored to her individual living environment, hobbies, and other demands. Thanks to this support, my wife was able to come home eight days after undergoing surgery. Full recovery will take time, but her face lights up as she talks about the places she wants to go and the things she wants to do in the coming years. (© Ōnishi Naruaki)

An Explorer to the Bone

Matsubara will be 70 next year. He still handles some 250 procedures a year, and appears remarkably youthful and active. He says he once dreamed of being an archaeologist, and in college, he developed a consuming passion for soccer. Then, he became an orthopedic surgeon, devoting himself to extending the frontiers of his profession.

Confronting the years means grappling with changes in our bones and joints—including the thinning of bone tissue, the deterioration of cartilage, and the atrophy of muscles supporting the joints. Dr. Matsubara has helped pioneer a more proactive approach to maintaining pain-free mobility as we age.

There are 206 bones in the adult human skeleton, and every one is unique.(© Ōnishi Naruaki)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Using X-ray images and printed templates, a medical team plans a hip replacement procedure at Nissan Tamagawa Hospital in Tokyo. © Ōnishi Naruaki.)